Where’s the Debate on Francis Scott Key’s Slave-Holding Legacy?

During his lifetime, abolitionists ridiculed Key’s words, sneering that America was more like the “Land of the Free and Home of the Oppressed”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a2/47/a2476b3c-23ad-4687-8bc7-94fa0a7bce0f/familyviewingssbinnewgalleryccweb.jpg)

Every 4th of July, I ask my family to sit down in front of the radio as if we’re tuning in to one of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats, the nationally broadcasted speeches the 32nd president made between 1933 and 1934. Ours is a family tradition of listening while National Public Radio personalities recite the Declaration of Independence.

Though the exercise works better in my head than it does in practice—it is always a challenge to get my nine- and six-year kids to sit quietly on a day promising parades and fireworks—I never fail to get something out of the experience.

And I think my children do as well.

We take a bit of time to contemplate the words and ideals that defined the nation. Something about paying attention solely to spoken words for a few minutes provokes deep discussion.

It is instructive and moving to hear the entire text in all its beautiful eloquence and with all the inherent irony of its rhetoric of freedom and equality contrasting with the realities of slavery and the treachery practiced on the “merciless Indian savages.”

When we consider the legacy of the Declaration and its author, Thomas Jefferson, we confront and debate this compelling paradox—that the man who trumpeted the “self-evident” truth that “all men are created equal” owned some 175 slaves.

We note the paradox underlying Jefferson’s authorship of the Declaration. It comes up all the time, as in the smash Broadway hit Hamilton when Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Alexander Hamilton takes Jefferson down a peg or two:

A civics lesson from a slaver. Hey neighbor

Your debts are paid cuz you don’t pay for labor

“We plant seeds in the South. We create.”

Yeah, keep ranting

We know who’s really doing the planting

However, we fail to do the same with our national anthem’s composer Francis Scott Key. “All Men are Created Equal” and “The Land of the Free”—both those mottoes sprang from the pens of men with quite narrow views of equality and freedom.

The seeming contradictions between Jefferson’s slaveholding history, deeply racist personal views, his support of the institution in his political life, and his assertion of human rights in the Declaration, in many ways parallel Key's story.

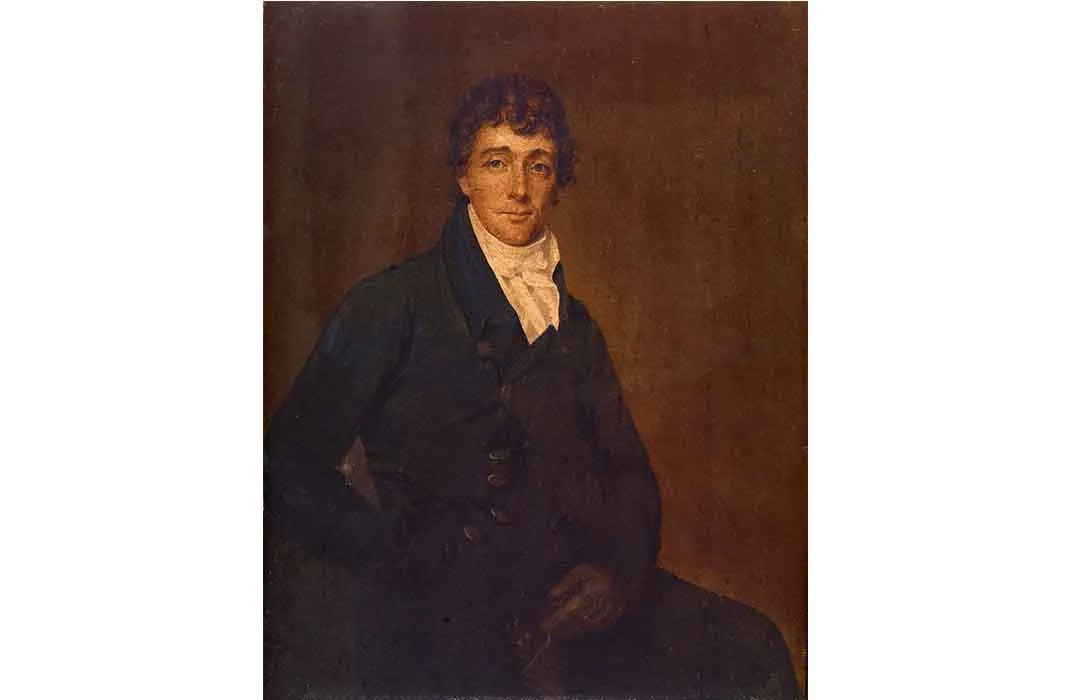

In 1814, Key was a slaveholding lawyer from an old Maryland plantation family, who thanks to a system of human bondage had grown rich and powerful.

When he wrote the poem that would, in 1931, become the national anthem and proclaim our nation “the land of the free,” like Jefferson, Key not only profited from slaves, he harbored racist conceptions of American citizenship and human potential. Africans in America, he said, were: “a distinct and inferior race of people, which all experience proves to be the greatest evil that afflicts a community.”

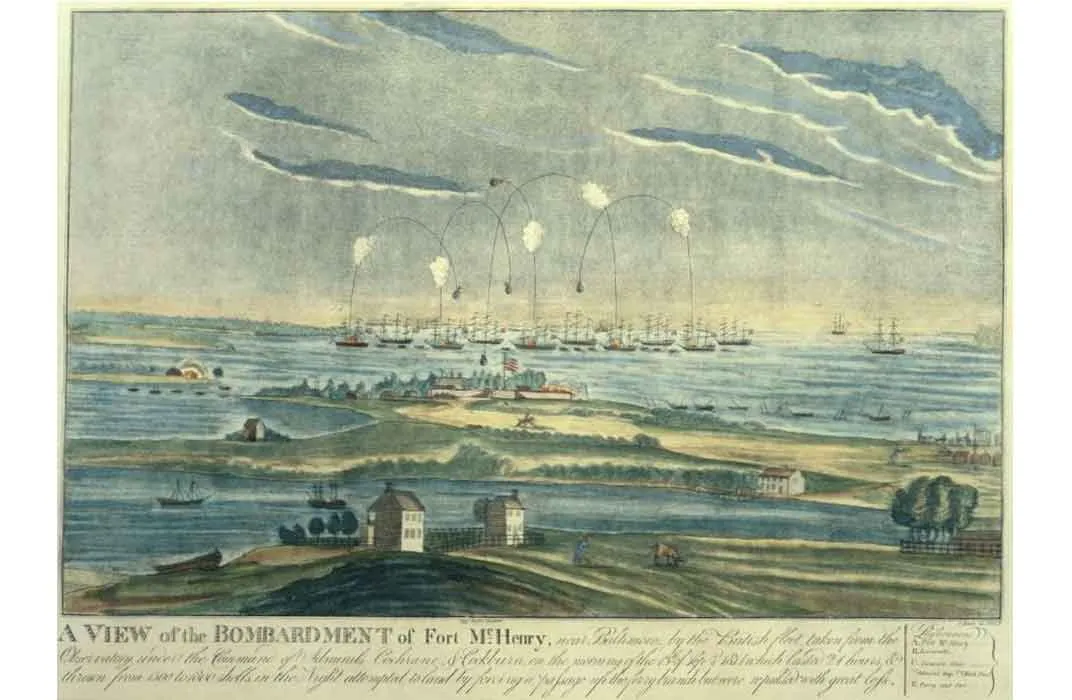

A few weeks after British troops in the War of 1812 stunned and demoralized America by attacking Washington and setting the Capitol building and the White House ablaze on August 24, 1814; the British turned their attention to the vital seaport of Baltimore.

On September 13, 1814, British warships commenced an attack on Fort McHenry, which protected the city’s harbor. For 25 hours bombs and rockets rained down on the fort, while Americans, still wondering whether their newfound freedom would really be so short-lived, awaited news of Baltimore’s fate.

Key, stuck aboard a British ship where he had been negotiating a prisoner release and barred by the officers of the HMS Tonnant from leaving because he knew too much about their position, could only watch the battle and hope for the best.

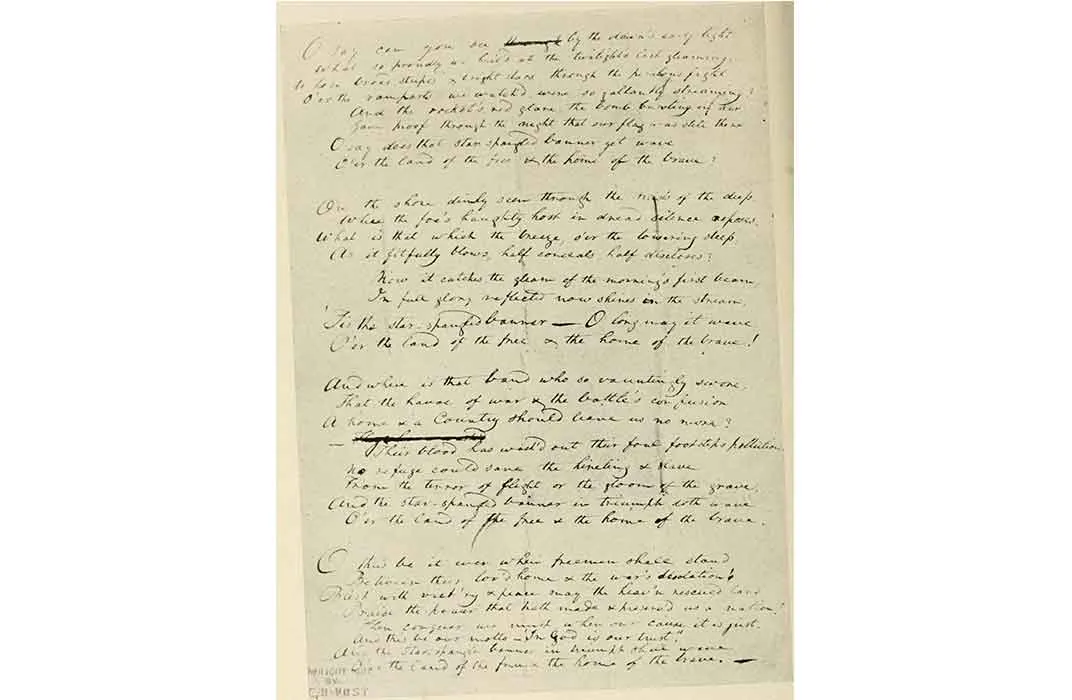

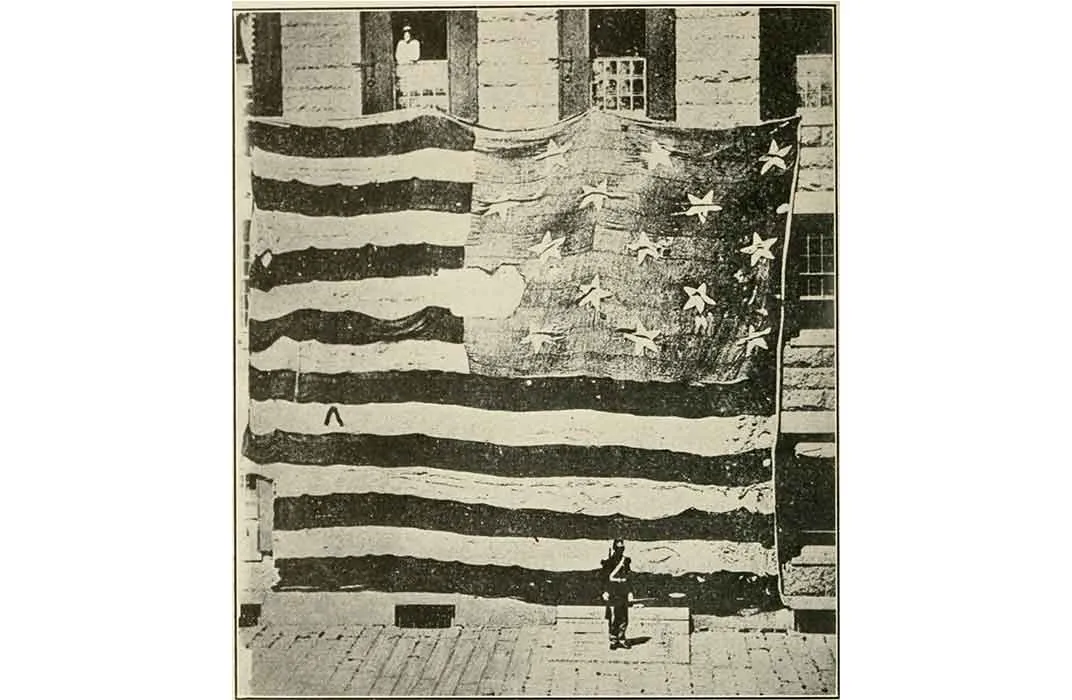

By the “dawn’s early light” of the next day, Key saw the huge garrison flag, now on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, waving above Fort McHenry and he realized that the Americans had survived the battle and stopped the enemy advance.

The poem he wrote celebrated that Star-Spangled Banner as a symbol of the resilience and triumph of the United States.

Ironically, while Key was composing the line "O'er the land of the free," it is likely that black slaves were trying to reach British ships in Baltimore Harbor. They knew that they were far more likely to find freedom and liberty under the Union Jack than they were under the “Star-Spangled Banner.”

Additionally, Key used his office as the District Attorney for the City of Washington from 1833 to 1840 to defend slavery, attacking the abolitionist movement in several high-profile cases.

In the mid-1830s, the movement was gaining momentum and with it came increased violence, particularly from pro-slavery mobs attacking free blacks and white abolitionists, and other methods to silence the growing cries for abolition. In a House of Representatives and United States Senate inundated with petitions from abolitionists calling for the ending or restriction of slavery, pro-slavery Congressmen looked for a way to suppress the voices of abolitionists.

In 1836, the House passed a series of “gag rules” to table all anti-slavery petitions and prevent them from being read or discussed, raising the ire of people like John Quincy Adams, who saw restricting debate an assault on a basic First Amendment right of citizens to protest and petition.

In the same year, shortly after a race riot in Washington, D.C. when an angry white mob set upon a well-known free black restaurant owner, Key likewise sought to crack down on the free speech of abolitionists he believed were riling things up in the city. Key prosecuted a New York doctor living in Georgetown for possessing abolitionist pamphlets.

In the resulting case, U.S. v. Reuben Crandall, Key made national headlines by asking whether the property rights of slaveholders outweighed the free speech rights of those arguing for slavery’s abolishment. Key hoped to silence abolitionists, who, he charged, wished to “associate and amalgamate with the negro.”

Though Crandall’s offense was nothing more than possessing abolitionist literature, Key felt that abolitionists’ free speech rights were so dangerous that he sought, unsuccessfully, to have Crandall hanged.

So why, unlike Jefferson, does Key get a pass—why this seeming contradiction?

Perhaps it is because the writer of the Declaration of Independence was also a president. And we judge, re-examine and reconsider the legacy of our presidents fairly rigorously.

Lincoln certainly gets taken to task despite the Emancipation Proclamation, the 13th Amendment, and the Gettysburg Address. Many Americans are acutely aware of the ways in which his record conflicts with the myth of the “Great Emancipator.”

However, while Key may not be as notable as a president, his poem is, and that was enough to make abolitionists ridicule his words during his lifetime by sneering that America was truly the “Land of the Free and Home of the Oppressed.”

Though we may have collectively forgotten Key’s backstory, it’s interesting to consider why this contradiction, which was so well known in the 19th century, has not survived in our national memory.

In fact, as the phrase that ends the song is so well-known, it’s also just odd to me that we rarely hear anyone take Key and the anthem to task for the simple fact that it would be so easy—“brave” rhymes with “slave,” for goodness sake.

How is it that neither Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X nor Public Enemy came up with lesser-known hip hop artist Brother Ali’s line, “land of the thief, home of the slave?”

Even when Malcolm X observed that this American motto was flawed, as he did in a speech in Ghana in May 1964, the irony of the background of its author and the exaltation of its ideals does not arise. “Anytime you think that America is the land of the free,” Malcolm told the African audience, “you come there and take off your national dress and be mistaken for an American Negro, and you will find out you’re not in the land of the free.” In this speech, however, despite being such an expert at pointing out inconsistencies, he doesn’t add, “in fact, ‘land of the free’ was written by a slaveholder!”

Does it matter if the author of a powerful and inspirational composition in the past held views and did things with which we would not agree today and which we would consider antithetical to the very American ideals his writing professed? Do we hold the Declaration of Independence to a higher standard than the Star-Spangled Banner?

We constantly make new meaning from our past. Recently, we have seen numerous examples of our rethinking of how we publicly remember the history of the Confederacy, or whether Harriet Tubman should replace Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill. Historian Pauline Maier argues that Lincoln played a huge role in reinterpreting the Declaration and making it into a motto or an “ancient faith” shared by all Americans.

In 1856 Lincoln suggested Americans needed to “re-adopt the Declaration of Independence and with it the practices and policies which harmonize with it.” Though we may have forgotten Key’s racism while we remember Jefferson’s, we have similarly washed it away from the song by adopting it as something to live up to.

Every time Jackie Robinson stood on the baselines as the anthem was played, or when Civil Rights Movement activists had the flag ripped out of their hands as they peacefully marched, or when my dad saluted the flag at a segregated army base in Alabama fighting for a nation that didn’t respect him, the song became less Key’s and more ours.

Though we should remember the flaws and failings that often animate our history, to me at least, they do not need to define it. We should remember that if, 200 years after it was declared so by a slaveholder and enemy of free speech, the United States is “the land of the free,” that is because of “the brave” who have called it home since dawn’s early light in September 1814.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kegley140407Wilson0014.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kegley140407Wilson0014.jpg)