Looking back, Geraldine “Jerrie” Mock might have said these were the things she preferred: a double shot of scotch over a bouquet of orchids. Pants instead of a skirt. And a trip around the world where she could’ve taken her own sweet time taking in the sights, instead of staring at the ceiling of a hotel, trying to sleep in preparation for her next flight.

Mock is the first female pilot to circumnavigate the world alone. During and after her ground-breaking 22,860-mile flight in 1964, the barely five-foot-tall pilot set 21 world records. “Just nobody else had the sense—or shall I say, the stupidity—to try it,” Mock told Air & Space magazine just before she died at the age of 88 in 2014. “There were women who told me that they flew because of me. I’m glad I did what I did, because I had a wonderful time.”

The mid-1960s was a time when few women worked outside of the home, much less climbed into the seat of an airplane, so Mock, the 38-year-old mother of three with her fashionably coiffed curls, became known in the press as “The Flying Housewife.” Her goal was huge; after all, she was attempting a feat similar to what had led to the 1937 disappearance and subsequent death of the famed aviator Amelia Earhart.

Mock hadn’t set out in search of fame, or even to redefine societal expectations, according to her granddaughter, the author Rita Mock-Pike, who is now telling Mock’s story in a one-woman show that is touring this fall. “She didn’t believe anyone should be kept back from their dreams,” says Mock-Pike, who remembers her grandmother as an avid storyteller. “It was her way of rebelling against society and saying, ‘No, you don’t get to tell me or anyone else who we are… If I could do this, anyone can do anything.’”

On October 14, when the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum reopens to visitors, Mock’s red and white Cessna 180 will hold pride of place in the new “Thomas W. Haas We All Fly” gallery, which explores the influence of general aviation on society, including in sports, business and humanitarian endeavors. “Geraldine Mock never doubted that she could do it,” says Dorothy Cochrane, the museum’s curator of general aviation. “That was what seems so unusual, because she seemed like a quiet, retiring housewife. Nobody knew that she had all this in her, and she just did it.”

To Mock, at least at first, her month-long flight was just about “having fun.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/67/62/67623879-194e-4228-ba48-b5a6eff58b02/51392372343_276509942f_k.jpg)

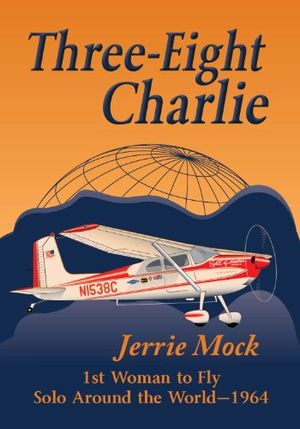

Three-Eight Charlie: 1st Woman to Fly Solo Around the World

Three-Eight Charlie is the story of Jerrie Mock’s record-setting flight as the first woman to solo around the world in 1964 in a single-engine Cessna 180. It’s an insightful and well written account that includes intrigue and heroism, and discusses the cultures and geography of the world at the time. This book is a great read for aviation enthusiasts as well as young people, and anyone with big dreams.

Jerrie Mock’s childhood

Born in 1925, Mock grew up during the Great Depression, when the expectation was marriage and family. For women, life ended there, says Mock-Pike. When she was seven, her father took her on a airplane ride in a Ford TriMotor. Looking down at the fields and streams below, Mock instantly knew that she was going to be a pilot, her sister Susan Reid recalled in the podcast Ohio v. the World. From that moment on, Mock declared that she had three dreams: she would ride a camel. She was going to see the pyramids in Egypt. And she would ride an elephant.

At the Ohio State University, she became the only woman in her aviation engineering class. At first, the other men looked down on her, that is until she scored the only perfect grade on a difficult chemistry exam. In 1945, she left college to marry Russell Mock, and the couple would soon have three children—Roger, Gary and Valerie.

But she was bored. “I’m just a housewife. I get tired of washing dishes and ironing clothes,” Mock told the Washington Record-Herald in 1964.

She found other ways to keep herself occupied. In the 1960s, she produced the television series "Youth Has Its Say," where she helped teenagers parse through current events, says Mock-Pike. She also became the writer and director of Opera Preludea, indulging her love for music in a weekly radio show that preceded broadcasts from the Metropolitan Opera.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f6/1d/f61d2999-f474-46ff-9621-f310e2aa800f/2.jpg)

Still, she needed something else. So while her sons were at school, she began taking flying lessons; and soon, she and her husband both were licensed to fly. They purchased the Cessna 180, naming it Spirit of Columbus after their Ohio hometown. Before long, Mock dubbed the aircraft “Charlie,” derived from its registration number N1538C, “Three-Eight Charlie” and the aviation alphabet code word for ‘C.’

“When she talked about Charlie, it wasn't the plane, it was Charlie. And he had his own personality in her mind,” says Mock-Pike. “It was as if Charlie was her friend and partner, this personality, this essence.”

How to fly around the world

One evening at dinner, while talking to her husband about how she thought her life should be more exciting, Russell Mock replied: “Why don't you just get on the plane and fly around the world?”

“Alright, I will,” she said.

The idea was at first a joke, but two years later, Mock was obtaining permissions and visas, charting flight paths, and working through a long checklist of items in preparation, including clearing foreign sanctions and getting permission from the National Aeronautic Association (NAA) in order to be considered the official record-bearer for circumnavigating the globe, says Cochrane.

She secured a $10,000 loan from The Columbus Dispatch to finance the trip—about $95,000 today. In addition, the Dispatch required articles from her, including exclusive interviews about her flight.

Mock was considerably less experienced than other pilots, having logged just 750 hours of flying time with only 250 hours of solo flight. She had never flown any further than the Bahamas, much less endured the 14-hour-long flights that she would need to do for some of the more tedious legs of her journey. While her plane, “Charlie,” was capable of handling a trip around the globe, it needed modifications—to the already cramped space, she added three extra fuel tanks, dual directional finders, short-range radios and a long-range high-frequency radio, which barely left her any space in the cockpit.

She packed a typewriter, two outfits and two pairs of shoes. Forsaking her much loved slacks and for the sake of diplomacy during her landings abroad, she wore a blue, drip-dry combo sweater and skirt.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d7/59/d7590629-76f9-48b5-a33f-428c5083a89f/joan_merriam_-_agana_guam_-_april_1964b.jpeg)

Less than three months before her departure, Mock discovered that another woman Joan Merriam Smith was planning to take the record. Smith was a better pilot than Mock, and she was more well-known in aviation circles, according to Cochrane. Even if Smith was not officially sanctioned by the NAA, if she beat Mock in coming back to the U.S., the public would acknowledge Smith as the first woman to fly around the world. “I hadn’t counted on a race when all this started,” she wrote, in her 1970 memoir Three-Eight Charlie: 1st Woman to Fly Solo Around the World. The press jumped on the story, turning it into a competition. Mock’s husband stepped up the pressure, reminding Mock that they were in “too deep” with their sponsors.

Worried that the Dispatch would pull its funds, Mock decided to leave two weeks earlier than planned and two days after Smith. She had hoped to spend a day at each place she landed taking in the sights, but in order to circumnavigate the globe and return home before Smith, her husband urged her to get off the plane, sleep the five required hours needed in order to fly again, and depart without seeing the city.

As she prepped for flight at the Columbus Airport, she was uncomfortable with all the attention around her—“I wanted to shout to everyone to go away,” but Mock was still excited for takeoff. This was her chance to finally achieve her dreams, and see the world, perhaps ride a camel, maybe an elephant. As her little Cessna took flight, she heard the tower controller remark: “I guess that’s the last we’ll hear from her.”

The comment would only solidify her resolve.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/72/a8/72a87ef7-1877-4fa6-bae7-fd061326b306/damsmdm_nasm-nasm-9a11714.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1e/bc/1ebcdc20-32e4-44e4-88a7-004483d17663/3.jpg)

Voyage of the "Flying Housewife"

Throughout the journey, her husband and the Dispatch pushed her to win the race, Russell Mock even mislead his wife about Smith’s whereabouts. (Smith, in fact, had fallen behind Mock in the race, “stuck in South America.”)

In the air for the first leg of the flight, Mock discovered that her long-range radio was inoperable. Later, she would find that the wire had been disconnected, and would suspect sabotage. But in that moment, as she stared out over the blue of the Atlantic Ocean, she was at peace. While she flew over land and sea, she told the The Washington Record-Herald in 1964, “I couldn’t get any good music on the plane’s radio.” So, she sang arias from Carmen, La Boheme, and William Tell.

“The kind of person who can sit in an airplane alone,” recalled Mock in a 2014 interview, “is not the type of person who likes to be continually with other people.” Though she preferred solitude, she was still honored when the crowds of people swarmed her at each landing. Flying barefoot, she would slip on her heels before stepping out of the plane, ready to look the part of her nickname, “The Flying Housewife.” In Saudi Arabia, where women would not be allowed to drive until 2017, the male onlookers were confused when she arrived. One stepped forward to peer around the cockpit, before shouting in astonishment that there was no man there. Mock received a “rousing ovation,” she wrote in her memoir.

Along the way, she would indeed ride a camel and see the pyramids, but did not get to ride an elephant. Mock-Pike says the journey inspired Mock’s passion for cooking and her extensive spice cabinet, as well as her large china collection. She loved visiting Casablanca, raving about the couscous and the time spent with ambassadors. After her flight, Mock would continue to receive letters and calls from her friends around the world. And in Morocco, where she danced in marble palaces, she brought back a chicken bastilla recipe. Recalling her flight over Vietnam, where the U.S. that year was bombing North Vietnamese supply lines, she wrote: "Somewhere not far away a war was being fought, but from the sky above, all looked peaceful."

However, the flight wasn’t all smooth sailing. Her sister, Susan Reid, remembered Mock’s setbacks and how she remained cool under pressure, “a skill that really couldn’t be measured.” She rivaled even the most experienced of pilots for her ability to assess the situation calmly and find a solution.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e1/f9/e1f979d6-f69b-4059-a136-6b3693cb93f9/23.jpg)

As she flew to Santa Maria in the Azores, ice formed on the wings, a problem that could lead to catastrophe. Fly too low, and the weight of the ice on the wings would cause her to crash. Fly too high, and she could lose control of the aircraft. So she flew above the clouds and waited for the sun to thaw the ice. She was also calm when her radio antennae began smoking over the Libyan desert, and when sand blew into her engine over Saudi Arabia.

While she was enroute to Cairo, her skill was diplomacy. Touching down on the tarmac, she knew something was wrong when armed soldiers appeared. Instead of the Cairo Airport, Mock had landed at a secret off-the-map military base. While she waited for clearance to leave, Mock watched television with the soldiers before heading off to the real airport. In her memoir, Mock jokingly called the incident the “April Fool’s landing.”

“I think it was an advantage to me that I learned to fly without instruments,” she told The Cincinnati Enquirer in 1979. “Many of the countries I flew over had very primitive facilities. If I had not learned to fly without instruments, I would surely have been lost.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ca/30/ca308a98-a9a7-41e9-9060-d5c0379b4490/19.jpg)

As Mock prepared to make her way back to Ohio, she was looking forward to visiting Hawaii, her final respite before flying 14 hours over the Pacific Ocean. However, according to her memoir, upon landing, she received a phone call from her husband, telling her that a “luau and other parties that had been arranged” for her visit had been cancelled at his urging so that she could sleep instead. “But I'm not tired. Not now that I'm here. How could you ruin things before I even got here?” wrote Mock, irritated by the interference. “With the crowd listening, I didn't say much more. It was not the time to get personal.” (The couple divorced in 1979, though her daughter Valerie and sister Susan said the pair would remain lifelong soulmates.)

On April 17, 1964, Mock completed her journey. Three weeks ahead of Smith, she arrived back home at the Columbus Airport. With much fanfare, state officials congratulated her on her achievement, with the governor declaring her “Ohio’s Golden Eagle,” and designating the date as “Jerrie Mock Day.” Her husband gave her orchids, but acknowledged she probably needed a double shot of scotch. With no time for rest, she made an appearance on the Today show and met with President Lyndon B. Johnson, who awarded Mock with the Federal Aviation Agency's "Decoration for Exceptional Service," along with a birthday cake for 4-year-old Valerie.

The Smithsonian asked for “Charlie,” and Cessna gave her an upgrade—a new Cessna P-206, while The Columbus Dispatch gifted Mock a golden globe necklace inlaid with rubies for every place she visited, and with a diamond to designate the city of Columbus. She was “tired but sparkling,” according to the Arizona Republic in 1964. Summing up her thoughts at the time, she wrote in an article for the Washington Record-Herald: “Traveling so far so fast, I have a whole jumble of impressions that I want to…sort out when I have time.” But the experience had certainly been fulfilling. “This is the way I believe life should be lived,” she concluded.

After the flight

But after her legendary flight, the ruby necklace was stolen, says Mock-Pike, and Mock couldn’t afford the taxes and upkeep on the new plane. But before she gave up flying, she took one more world trip. While searching for a new home for the Cessna P-206, she decided to donate the aircraft to the Flying Padres, or the National Association of Priest Pilots, working in Papua New Guinea. She would fly the plane to the missionary Father Tony Gendusa so that he could use it in the jungles to ferry patients and medical supplies. To make the long distance flight, she sat on top of a fuel tank padded with five gel cushions, which would give her long-term hip damage. Once she handed over the keys, she flew commercial to see her friends around the globe, says Mock-Pike, bringing back dozens of gifts and souvenirs.

Back home, she’d become the manager of the Highland County Airport. Her days were now occupied by grass cutting, gasoline pumping and other chores at the airport.

Although she remained as “energetic as ever,” the Cincinnati Enquirer wrote in a 1979 tribute, her efforts to monetize her record-breaking flights never panned out and the financial burden of her loan made new ventures impossible. She wanted to open a restaurant called “Phoenix International Skyways,” featuring the recipes she gathered, like “Hungarian Chicken Paprika” and “Crepes Florentine.” She had quite a taste for Indian food, according to Mock-Pike.

Instead, she would assist with local literacy efforts in libraries, Mock-Pike says, telling them stories of her time around the globe. “She was very fascinated by watching the world change,” says Mock-Pike.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/36/b8/36b8862b-0103-4485-9f4b-01f5b8f3cc36/3990h.jpg)

She never lost her spunky character. When Mock was invited to the National Air and Space Museum after her airplane “Charlie” went on view, the 82-year-old former pilot didn’t want to fly a commercial airline, says Cochrane, because her little town was just too far from an airport. One of the museum’s docents was a pilot who decided to go get her and bring her to the nation’s capital. Upon landing at a small airstrip near the Chesapeake Bay, she set her sights on the local fare: “Okay, I’m ready for my crab cakes,” she said.

At the museum, she saw Charlie one last time. “She was happy as a clam talking to people all day,” says Cochrane.

Mock tended to brush off her achievements, says Mock-Pike, but then she began to understand the power of her own story and how she could be an influence for young women. “I remember her coming into this awakening period,” says Mock-Pike. “As she started talking to these young girls and other pilots, she realize that her story was more significant than she sometimes made it out to be…It wasn't just this self-contained achievement, but it's something that other people could aspire to their dreams, as well.”

Jerrie Mock’s legacy

While Mock continued her duties at the airport, she would be rediscovered multiple times by reporters who stumbled on her story, and who would write articles with headlines like, “Local Hero Unknown in Hometown,” as The Newark Advocate did in 1991.

For decades, Bill Kelley, a local fan who had witnessed her historic 1964 return to Columbus, had tried to garner more attention for her heroic flight, even offering to mortgage his house, to fund a statue in her honor. In 2011, he joined forces with Mock’s sister Susan Reid to begin a fundraising campaign to build a statue commemorating her accomplishments.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/27/a3/27a3e588-6242-41c3-888f-6b67c673ea49/img_4525.jpg)

On the 50th anniversary of her flight, Mock was unable to attend the unveiling of the new statue but watched the Columbus ceremony online. While Mock would say that she didn’t understand all the fuss, her children noticed her wiping away her tears.

In 2017, professional pilot Shaesta Waiz, the first certified civilian female pilot from Afghanistan, became the youngest woman to circumnavigate the globe. She credits Jerrie Mock for inspiring her career.

“There are so many people who need inspiration and encouragement to pursue their dreams. And that was one of my grandma's passions, to inspire and encourage people,” says Mock-Pike. “If you have a dream, pursue it, don't let other people tell you that you can't.”

Mock-Pike’s one-act play is keeping her grandmother’s memory alive. She is busy putting together the cookbook Mock never could, as well as recording an audiobook reading of her grandmother’s memoir, Three-Eight Charlie.

Mock never appreciated the nickname “The Flying Housewife;” evidence proves she was no ordinary housewife, but a fierce record-breaker. But more than that, she was a person with dreams and the temerity to achieve them.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3c/3c/3c3cb63f-1e8b-4552-83ed-eaef962bb7eb/untitled-1.jpg)