On March 25, 1931, in Chattanooga, Tennessee, several black teenaged boys hopped aboard an Alabama-bound freight train where they encountered two young white women. At that time, under those circumstances, what followed—nine youths being wrongfully convicted of rape—was among one of the first times the world got to see what happened when African Americans encountered the criminal justice system.

“What you have is a tale of convenience that’s told because people of two races are found socializing together in the rural South, and that’s the only way that Jim Crow society can justify or explain what’s going on,” says Paul Gardullo, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Making false accusations against the African Americans youths, was “the way that those white women were encouraged to respond by wider society.”

In the end, the ordeal 90 years ago of those who became known as the Scottsboro Nine “became a touchstone because it provided a searing portrait of how black people were too often treated in America,” says Gardullo. Decades of injustice would follow and the nine young men would spend a combined total of 130 years in prison for a crime they did not commit. What happened in the case would create an enduring legacy. The African American fight for equal rights, harnessed through the media, in art, politics and protest, would capture the world's attention.

In his 2020 memoir, A Promised Land, Barack Obama recalls a passage in W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folks, which was published in 1903. Obama wrote that Du Bois defined black Americans as the “perpetual ‘Other,’ always on the outside looking in . . . defined not by what they are but by what they can never be.”

Rape charges, in particular, fit a pattern. There has been “a myth of black predation on white women when the reality was the polar opposite. . . . black men, women and children were degraded and often victimized and particularly black women were raped, and worse, by white men for generations, under slavery,” Gardullo says.

The Scottsboro Nine’s case, however, became a moment showing that despite their status as outsiders, black Americans could carry their calls for justice across the nation and around the globe. The journey through the judicial system of nine defendants included more trials, retrials, convictions and reversals than any other case in U.S. history, and it generated two groundbreaking U.S. Supreme Court cases.

Some historians view it as a spark that fired the mid-20th century civil rights movement. While the Scottsboro Nine wore the faces that represented a great tragedy, their survival represented “an opportunity for people to meditate on how this injustice could be rectified,” says Gardullo.

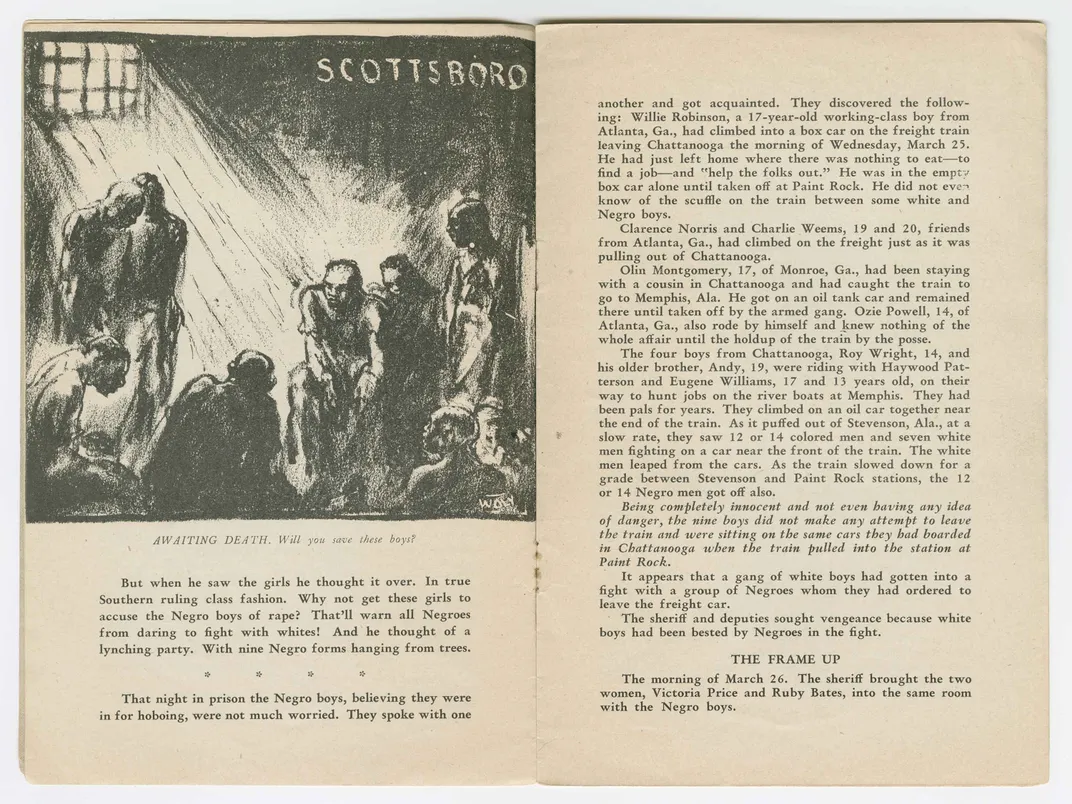

Among those riding on the train that day in 1931 were young hoboes, both white and black, men and women. At one point, a white man stood on the hand of 18-year-old Haywood Patterson, who would become one of the Scottsboro Nine, and almost knocked him off the train. A fight broke out, and the black travelers ousted the white travelers, forcing them off the train. The defeated white youths spread word of what had happened, and an angry, armed mob met the train in Paint Rock, Alabama, ready for lynchings. But the nine suspects, only four of whom knew each other, were arrested, taken into police custody, and transported to the nearby town of Scottsboro.

Later, the National Guard was summoned to disperse a violent crowd of vigilantes surrounding the jail. For their safety, the defendants ultimately were imprisoned 60 miles away.

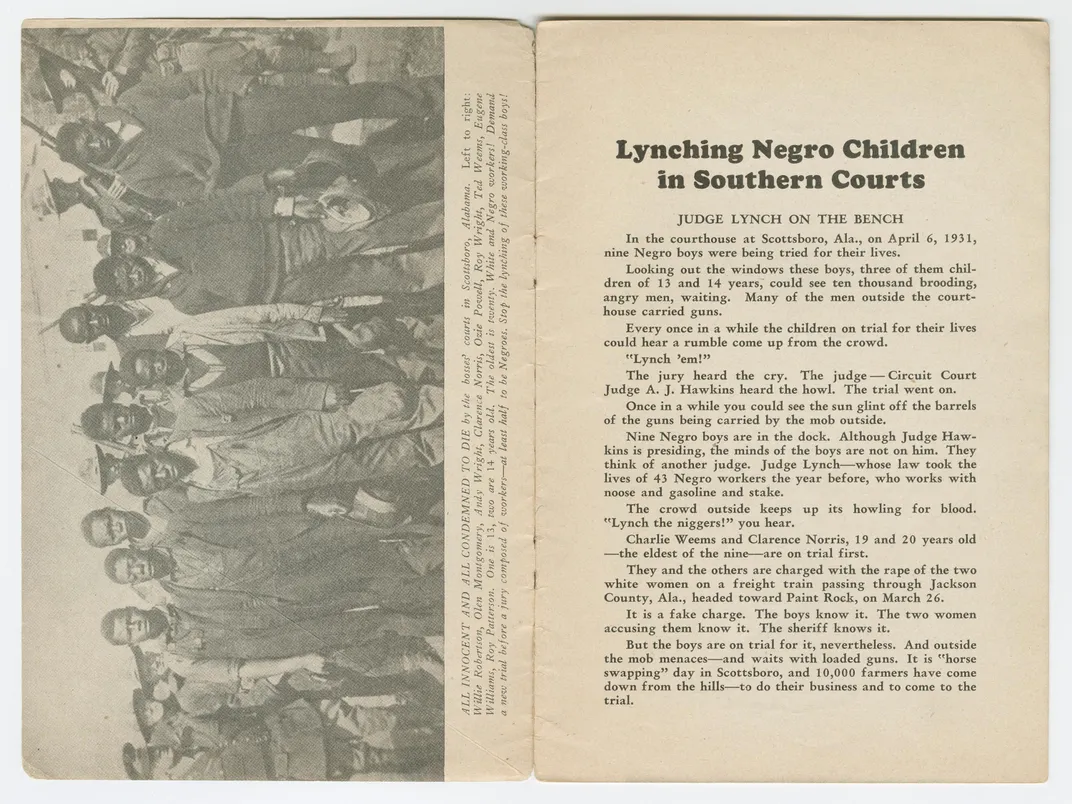

The accused, ranging in age from 13 to 19, faced allegations of raping Ruby Bates, 17, and Victoria Price, 21. The women told police they were going from city to city seeking mill work; as hoboes themselves, the women might have been tried on charges of vagrancy and illegal sexual activity if they had not accused the black men. Their testimony was weak. Nevertheless, a grand jury indicted Charlie Weems, 19, Ozie Powell, 16, Clarence Norris, 19, Andrew Wright, 19, Leroy Wright, 13, Olen Montgomery, 17, Willie Roberson, 17, Eugene Williams, 13, and Patterson within a week. Represented by a retiree and a real estate attorney, eight were tried, convicted by an all-white jury less than a month after the alleged crime, and sentenced to death. The trials consumed just four days. The case of Leroy Wright ended with a hung jury when some jurors thought that a life sentence would be more appropriate, considerng his youth, than execution. A mistrial was declared, but Wright remained in custody.

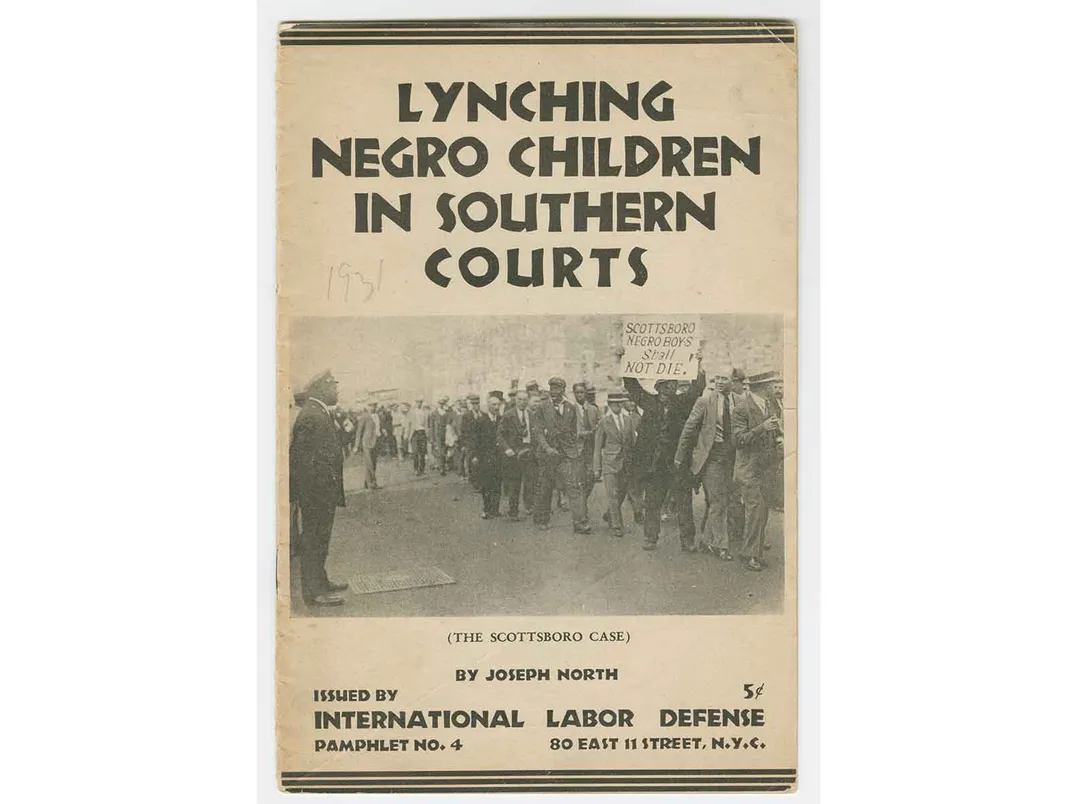

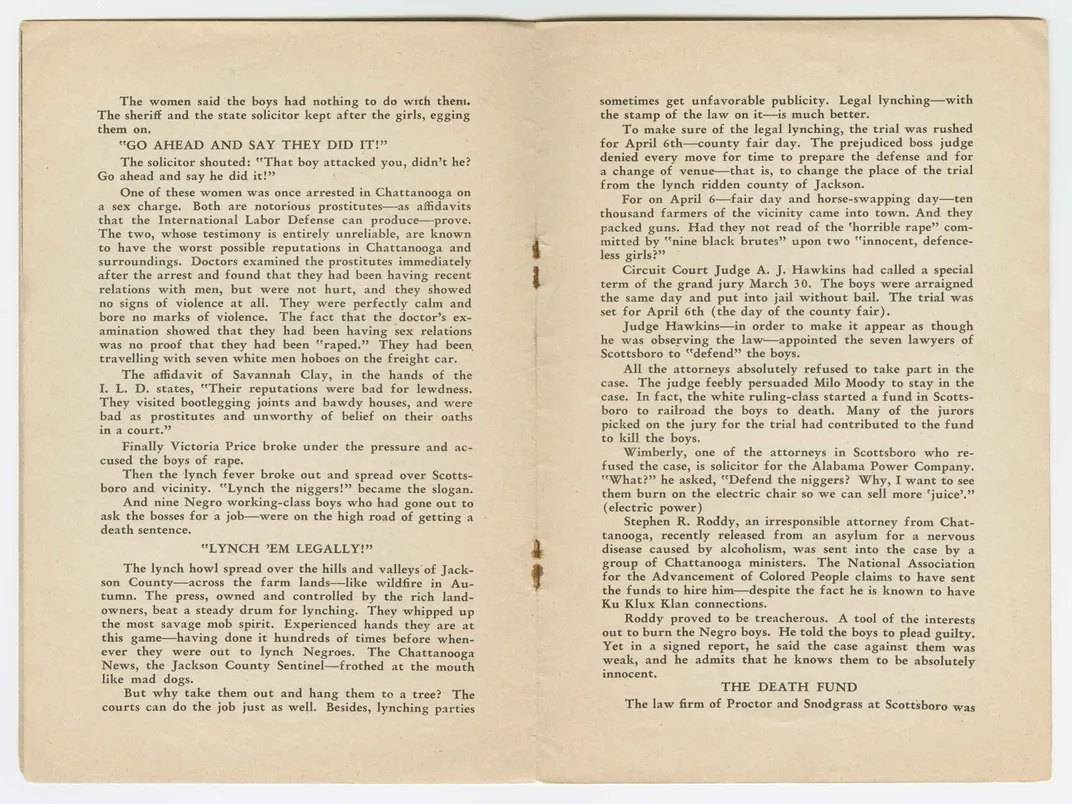

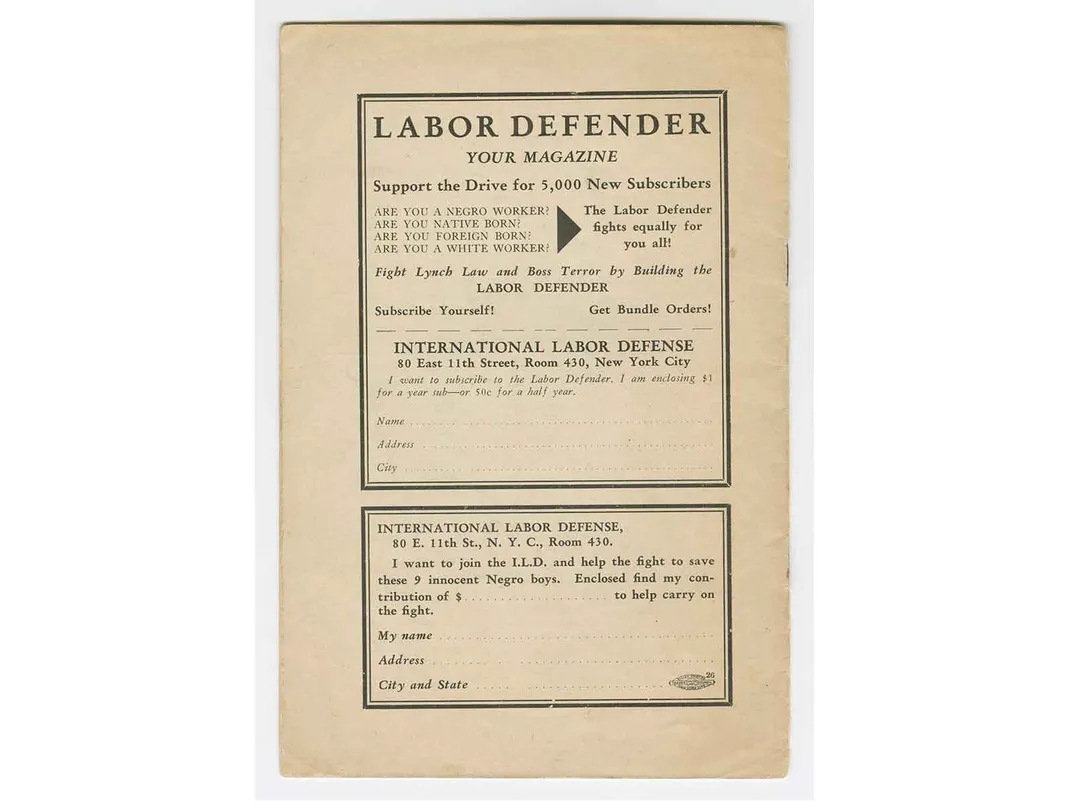

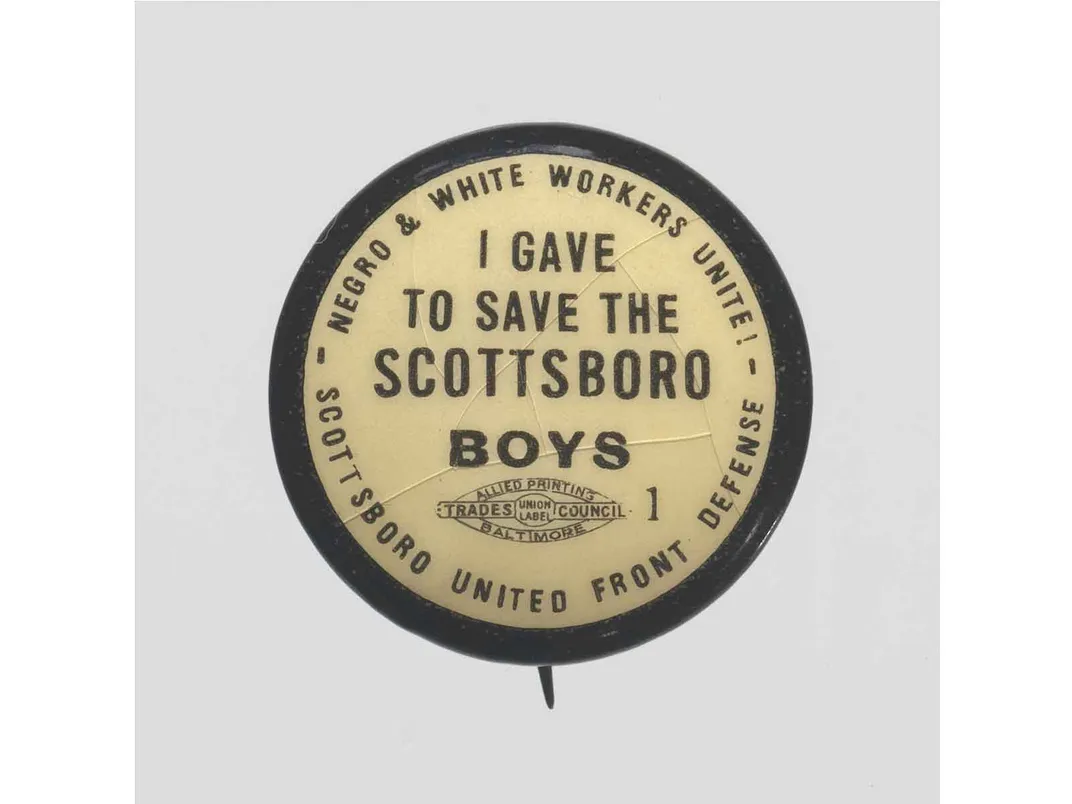

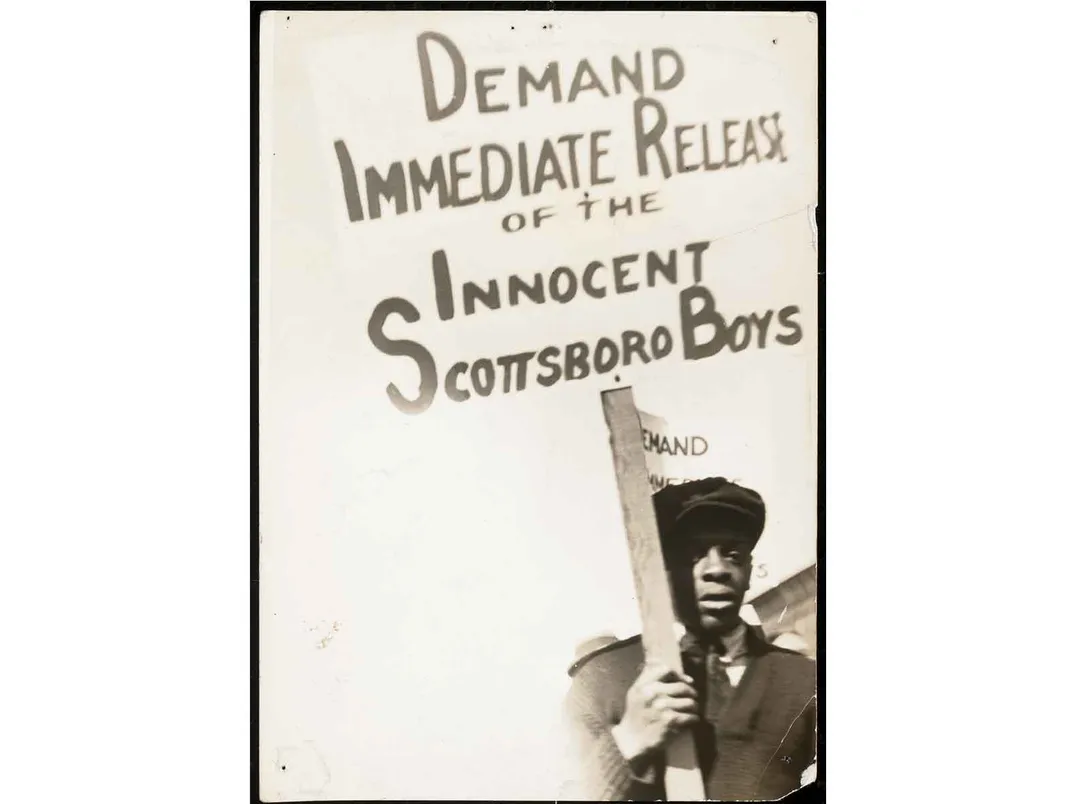

After the first trial, the American Communist Party jumped into the case, seeing it as an opportunity to win over minority populations and to highlight inequities in American culture. In June 1931, the youths won a stay of execution while the party’s legal arm—the International Labor Defense—appealed the verdict. The ILD launched a national effort to win support for the Scottsboro Nine through public gatherings, such as parades, rallies and demonstrations. However, roughly a year after their arrests, the Alabama Supreme Court upheld convictions of all but Williams, who was granted a new trial because he was a minor and should not have been tried as an adult.

Nevertheless, in a ruling on Powell v. Alabama, the U.S. Supreme Court determined in November 1932 that due process had been denied because the young men had not been given the right to adequate counsel in the original trial. This decision set new trials into motion. Bates recanted her testimony in Patterson’s case, which was the first to be retried; however, an all-white jury convicted Patterson and again sentenced him to death. Judge James Horton overruled the jury and ordered a new trial. (Apparently because of this ruling, Horton was voted out of office the following year.) In an additional series of trials, all-white juries reached more guilty verdicts and again issued death sentences.

For a second time in April 1935, the U.S. Supreme Court stepped in. This time, in Norris v. Alabama, the court overturned the convictions on the grounds that the prosecution intentionally eliminated black prospects from the jury.

Over time, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and other civil rights organizations worked alongside the ILD, forming the Scottsboro Defense Committee to prepare for upcoming retrials. Despite the many legal and illegal obstacles African Americans faced in the 1930s, Gardullo notes that their response to this trial was proactive. African American activists made the most of the attention drawn to the case. When different organizations vied for the right to represent the interests of the Scottsboro Nine, “African American men and women utilized them and attempted to shape those organizations to meet their needs,” he says.

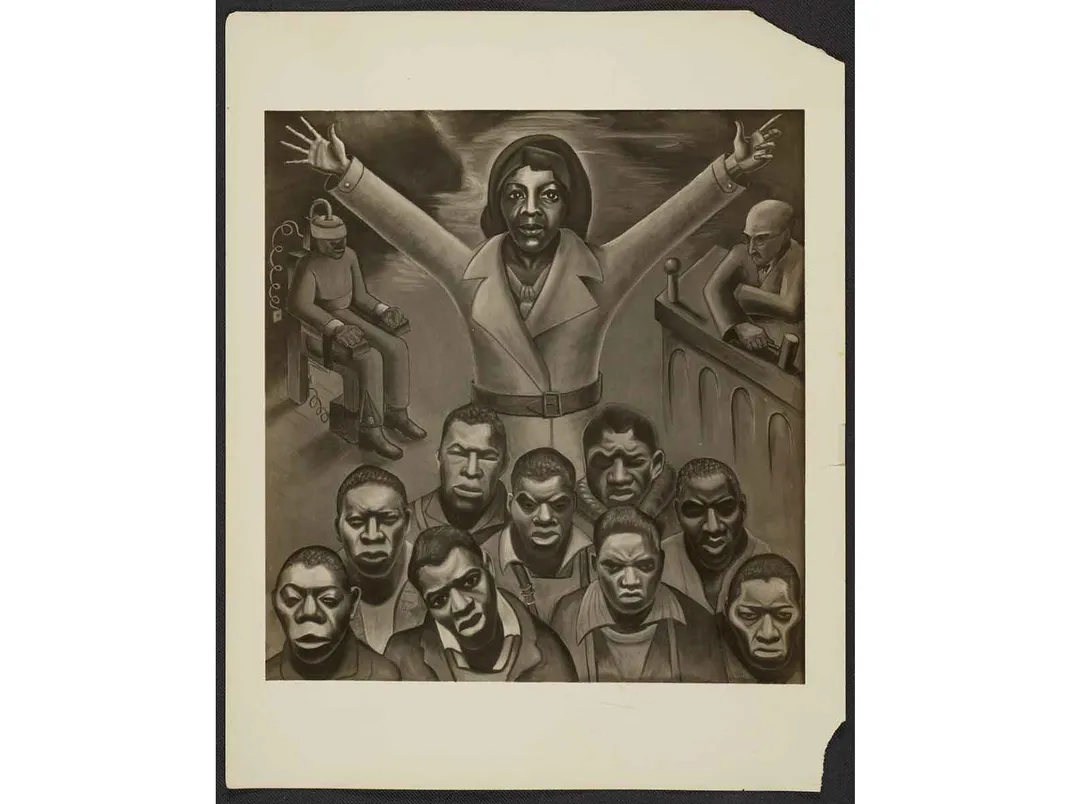

In a 1936 photograph held at the National Portrait Gallery, eight of the nine Scottsboro defendants appear with NAACP representatives, including two black women lawyers. The ninth defendant, a frustrated Leroy Wright, rejected a request to pose. Looking at the photo, Gardullo says, “I think the most obvious thing to understand is the fact that the world called them ‘the Scottsboro Boys,’ and these were young men. He also notes that “they are dressed well beyond their economic status. These were poor people.” Furthermore, the photograph “masks the fact that they are incarcerated.” At the National Museum of American History’s Archives Center, another photo shows mothers of the defendants alongside Bates, who traveled internationally with them following her recantation, to draw attention to the case, in what Gardullo calls “an early act of truth and reconciliation.” A notable pastel 1935 portrait of Norris and Patterson by Aaron Douglas also resides in the National Portrait Gallery along with another dated 1950 of Patterson. Other artifacts in the African American History Museum include protest buttons and posters used as part of their defense.

In early 1936, a jury convicted Patterson for the fourth time, but his sentence was lowered from death to 75 years in prison. “I’d rather die than spend another day in jail for something I didn’t do,” he said. A day later, Powell was shot in the skull after he pulled a knife on a deputy sheriff. Powell survived the injury but suffered lasting damage. Rape charges against him were dropped. He pleaded guilty in the assault on the officer and was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

During the summer of 1937 when four of the Scottsboro Nine were convicted again, another four—Montgomery, Roberson, Williams, and Leroy Wright—were released after authorities dismissed rape charges against them. Authorities labeled Roberson and Montgomery as innocent and indicated that Williams and Wright were being shown clemency because they were minors when the alleged crime occurred. An attorney picked up the newly freed men and drove them to New York City, where they appeared on stage in Harlem as performers and as curiosities. Montgomery and Leroy Wright participated in a national tour to raise money for the five men still imprisoned. Wright had a brief musical career, and well-known entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson paid his tuition to vocational school. Later, Wright served in the army and joined the merchant marine. He killed his wife and himself in 1959. Several defendants had difficulty reclaiming their lives after their ordeal.

Weems, who was tear-gassed and stabbed in prison and contracted tuberculosis, was paroled in 1943. Norris was released in 1944, rearrested after violating the terms of his parole, and freed again in 1946. Powell also achieved freedom in 1946. Andrew Wright, when freed in 1943, fled Alabama and was taken back to prison, where he remained until May 1950. Patterson escaped in 1948 and reached Detroit. Michigan’s governor refused to extradite him.

In 1976, Alabama Governor George Wallace, a staunch segregationist, pardoned Norris, the last living defendant. Though Norris was able to live until 1989 in freedom, he also spent his final decade unsuccessfully seeking a meager compensation from the state for the decades of injustice committed against him. During the second decade of the 21st century, the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles unanimously approved posthumous pardons for Andrew Wright, Patterson and Weems, thus clearing the names of all nine.

The Scottsboro Nine’s ordeal, with its mixture of human tragedy and horrific discrimination, captured the imaginations of writers, musicians and artists. After visiting the nine defendants, literary star Langston Hughes wrote a play and several poems about the case in the 1930s. The case inspired Harper Lee, who wrote the best-selling and Pulitzer Prize-winning novel To Kill a Mockingbird published in 1960. Her book focused on a single black man wrongly accused of raping a white woman of questionable character. The story of the nine youths found new life in a Broadway musical, The Scottsboro Boys, that opened in 2010 and offered the surprising combination of a huge American tragedy and an entertaining American musical.

“Scottsboro matters today,” Gardullo says, “because its actual history and the history of its aftermath (or the way it has been remembered or used in law, movement politics and popular culture) are essential for us to remember. The parallels to today—whether they are parallels of injustice (such as police brutality, institutional racism within the . . . justice systems, and stereotyping) or parallels of liberatory struggle (such as the Mothers of the Movement and/or movements like #SayHerName or Black Lives Matter) are not perfect. But through Scottsboro we find that America’s tortured racial past is not so past. Important also is that we can find the seeds of inspiration, and strategies for liberation or racial justice, in that past as well.”

:focal(314x145:315x146)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/0a/f10add4f-a32d-4362-9555-0c7da04a1fc2/scottsboro_mobile.jpg)

:focal(1019x295:1020x296)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/05/f505592b-20b4-4461-b474-b9688c64c5da/234.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)