The air inside the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum is electric with collective Black joy. It is Sunday, August 20, 1972, the afternoon of the storied Wattstax concert, a seven-year community commemoration following the 1965 Watts neighborhood uprising against police brutality and systemic discrimination.

Attendees laugh, joke and jostle through the stadium’s classically domed entryways, some with $1 tickets in hand, others admitted for free depending on what they can afford. By the time everyone is seated, more than 112,000 spectators, most of them African American Los Angeleans—dancing teenagers, multi-generational families, gang members, blue-collar workers anticipating a day of fun before the start of a new work week—people the rows with a range of brown complexions. It is reportedly the largest gathering of African Americans since the 1963 March on Washington and even before the music performances begin, it is living art.

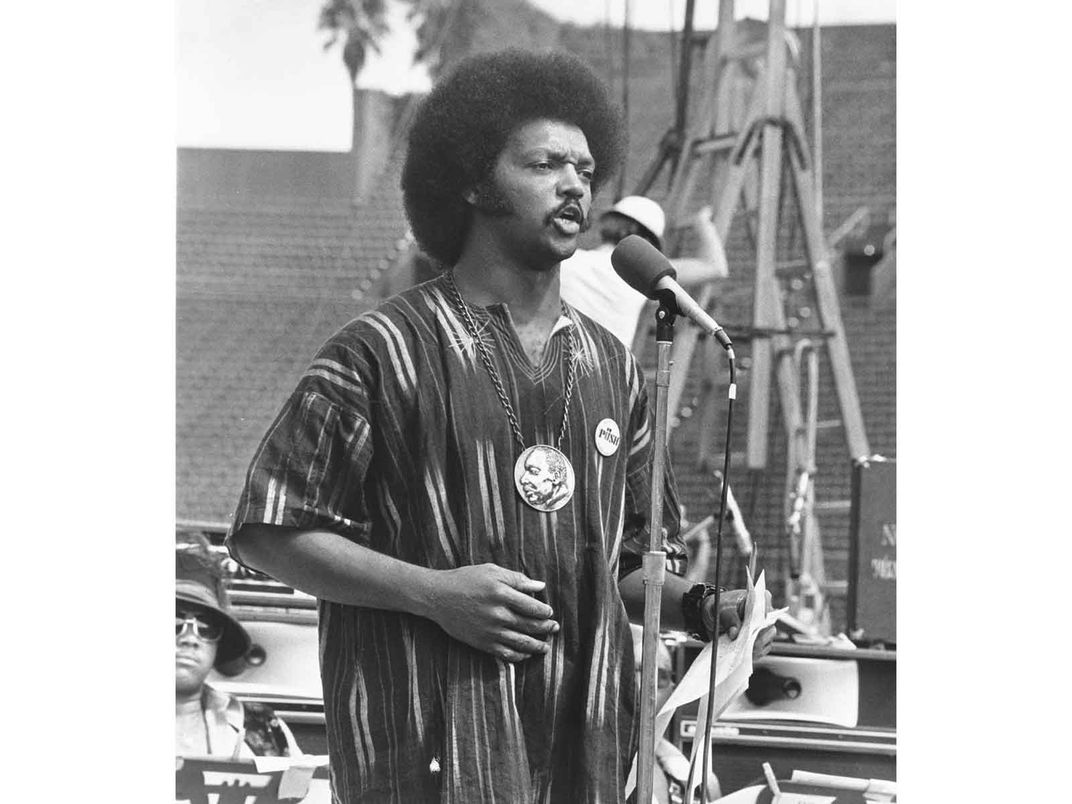

On the stage, erected in the center of the field just hours after a home game between the Los Angeles Rams and the Oakland Raiders the night before, Rev. Jesse Jackson ignites the crowd with his signature call-and-response recitation of “I Am Somebody.” By its final lines, thousands of fists are raised in the air in a solidarity salute to Black power. Jackson capitalizes on the euphoria of the moment to take the people even higher: “Sister Kim Weston,” he announces, “The Black National Anthem.”

Weston clutches the microphone, her cappuccino-colored skin glazed by the midday sunlight. If anyone in the house has never heard “Lift Every Voice and Sing”—affectionately referred to as “the Black National Anthem”—hers is the perfect introduction to it.

The notes purr from her throat, vibrating with pride and sincerity, and she holds them unrushed to compel her audience to soak in the hymn’s distinguished place of honor in the Black musical canon, the African American story set to song.

Lift every voice and sing

Till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise

High as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

In an inherent Africanism, Weston extends an invitation for the community to join her as she soars to the chorus. “Won’t you sing it with me everybody?” she asks. Having memorized the entire hymn from its repeated incorporation into church services or school assemblies or performances led by youth choir directors, the crowd responds as an ensemble of tens of thousands of voices, stumbling and mumbling over some parts, their fists still raised emphatically in the sky.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us,

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun

Let us march on till victory is won.

“Lift Every Voice and Sing” sets an atmosphere of reverence and gratitude—for the American journey of Black people, for the selfless sacrifices of the ancestors, for an inheritance of indomitability and resilience—and on the Wattstax stage, the hymn elevates the celebration of Black pride.

“It’s one of the highlights of my life,” says Weston, reached recently at her home in Detroit. Reflecting on the song’s powerful resonance, she says: “I’ve been singing ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’ since I was five years old. I learned it in kindergarten—we sang it every day. So that performance was a beautiful moment of solidarity.”

This year, the NFL announced that “Lift Every Voice and Sing” will be played or performed in the first week of the season, an acknowledgement of the explosive social unrest and racial injustices that have recently reawakened the American conscience. Just two years ago, team owners banned Colin Kaepernick and other players from silently protesting the same crimes against Black humanity by taking a knee during the “Star-Spangled Banner.” Weston believes the gesture indicates progress.

“You know what? I sang ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’ at the first inauguration of President G. W. Bush,” Weston says. “I think that that's the same thing he was doing, showing the Black community that there is some concern. What do they call that, an olive branch?”

In 1900, James Weldon Johnson composed the poem that would become the hymn that, in the 1920s, would be adopted by the NAACP as the official Negro National Anthem. A prototypical renaissance man, Johnson was among the first Black attorneys to be admitted to the Florida bar, at the same time he was serving as principal of the segregated Stanton School in Jacksonville, Florida, his alma mater and the institution where his mother became the city’s first Black public-school teacher.

Tasked with saying a few words to kick off a celebration of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, Johnson opted to display another one of his many gifts by writing a poem instead of a standard, more easily forgettable speech. He wrestled with perfecting the verses, and his equally talented brother J. Rosamond Johnson, a classically trained composer, suggested setting them to music. A chorus of 500 students sang their new hymn at the event.

When the two brothers relocated to New York to write Broadway tunes—yet another professional pivot in Johnson’s illustrious career—“Lift Every Voice and Sing” continued to catch on and resonate in Black communities nationwide, particularly following an endorsement by the influential Booker T. Washington. Millions more have sung it since.

“The school children of Jacksonville kept singing it, they went off to other schools and sang it, they became teachers and taught it to other children. Within twenty years, it was being sung over the South and in some other parts of the country,” Johnson wrote in 1935. “Today the song, popularly known as the Negro National Hymn, is quite generally used. The lines of this song repay me in elation, almost of exquisite anguish, whenever I hear them sung by Negro children."

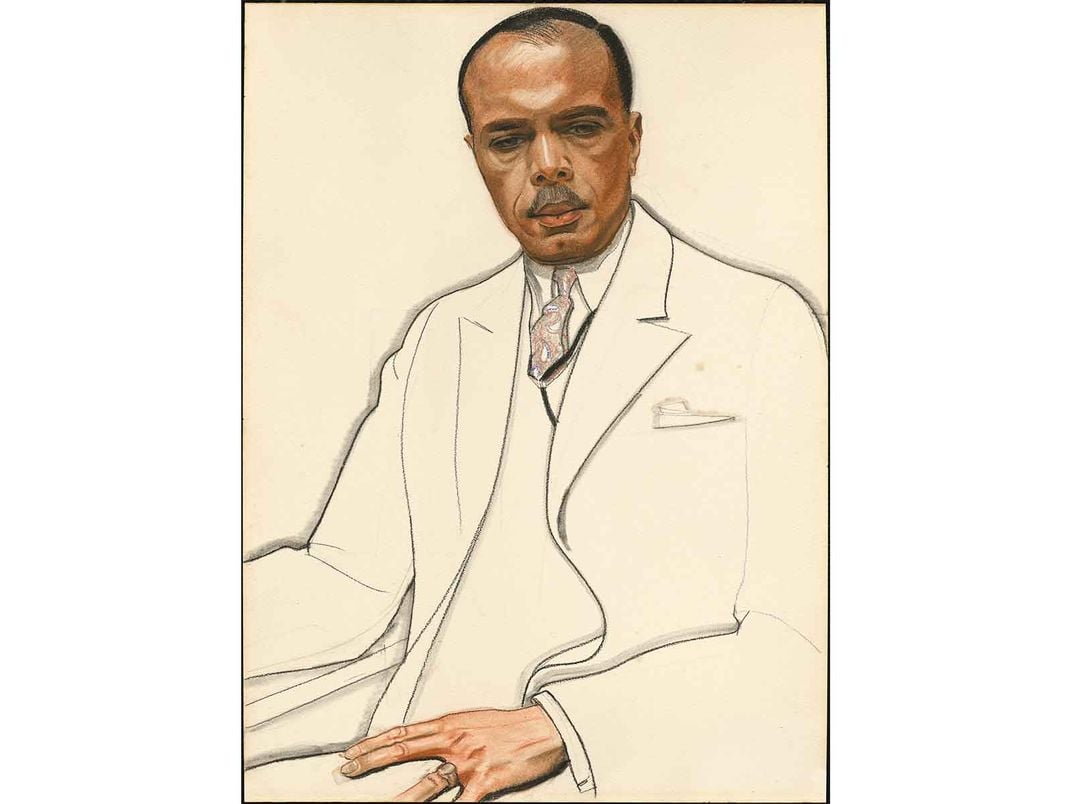

Sometime in the 1920s, Johnson sat for German artist Winold Reiss, who famously memorialized W.E.B. DuBois, Zora Neale Hurston and other luminaries from the Harlem Renaissance. The drawing is held in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery as a tribute to Johnson’s diversely distinguished life and career. After writing the Black National Anthem, he was appointed United States consul first to Venezuela, then Nicaragua by the Roosevelt administration. He went on to serve as field secretary for the NAACP, opening branches and enlisting members, until he was promoted to chief operating officer, a position that allowed him to outline and implement foundational strategies that incrementally combatted racism, lynching and segregation and contributed to the eventual death of Jim Crow laws.

The prestige of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” has become part of its legacy, not just for its distinguished lyrics but for the way it makes people feel. It inspired legendary artist Augusta Savage to create her 16-foot sculpture Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp) for the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Black servicemen on the frontlines of World War II sang it together, as have civil rights demonstrators in every decade, most recently on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial following the murder of George Floyd. President Obama joined the chorus of celebrity guests performing it at a White House civil rights concert. Beyoncé included it in her stunning Coachella performance in 2018, introducing it to a global audience who may not have known it before. It’s been recorded by Weston, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, and across all genres—jazz, classical, gospel, opera and R&B.

Though Johnson’s lyricism references key symbols from black history and culture—the “bright star” alludes to the North Star that guided men and women fleeing from enslavement to freedom, for example—he never draws an explicit connection to race. That means the anthem isn’t proprietary or exclusive to Black people, says Tim Askew, professor of English and humanities at Clark Atlanta University and author of Cultural Hegemony and African American Patriotism: An Analysis of the Song ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing.’

“A Black National Anthem is amazing. It is. But the song is an anthem of universal uplift. It's a song that speaks to every group that struggles. When you think of the words “lift every voice,” of course as a Black person, I see the struggles of Black people. But I also see the struggles of Native Americans. I see the struggles of Chinese Americans. I see the struggles of women. I see the struggles of gays and lesbians. I see the struggles of Jews. I see the struggles of the human condition. And I have to talk about that,” says Askew, who has had an academic love affair with the hymn for nearly 40 years.

“Lift Every Voice and Sing” has been sung by Mormons, Southern white folks and congregations around the world, appearing in more than 30 church hymnals. Rabbi Stephen Wise of the Free Synagogue in New York wrote to the Johnson brothers in 1928, calling the hymn the “noblest anthem I have ever heard.” That, says Askew, is a testament to the song’s universal magnetism beyond the defining lines of race and religion.

“The greatest compliment to James Weldon Johnson and his brother, these two black men, and to black people in general, is that something that comes from our experience became global. People around the world are hearing it and relating to it and responding to it,” says Askew.

Scholars, particularly Wendell Whalum at Morehouse College, have dissected the emotional progression through the three stanzas of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” from praise (see words like “rejoicing,” “faith” and “victory”) to lament (see “chastening rod,” “blood of the slaughtered,” “gloomy past”) to prayer (see “keep us forever in the path, we pray”).

Equal parts honoring the painful past and articulating optimism for the future, the hymn may be Johnson’s most well-known contribution because its lyrics remain relevant to where we are as a country in any era, says Dwandalyn Reece, curator of music and performing arts at the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Johnson speaks to a larger trajectory that really shapes us all. The struggle we're seeing today is not just between Black and white, it's for all people. We need everyone to stand up and speak out and get engaged in really changing society.”

As essential as Johnson’s genius poeticism, she adds, is brother Rosamond’s genius composition. “We always talk about the lyrics but I think the music is just as important—the majestic sound, the steadfastness, the sturdy beat. You get to these highs where you just want to sing at your loudest and assert who you are. There’s a tremendous amount of power when the lyrics and music are married together,” says Reece. “For me, it’s always kind of uplifting, particularly in a moment of despair or a moment of remembering why you're here, what got you here and the possibility that you want to imagine for yourself.”

That aspiration and hopefulness was in the faces of the thousands of people saluting their people—and themselves—at Wattstax as Kim Weston delivered what may have been the most notable performance of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” until that time and arguably of all time, certainly the first to resuscitate its widespread popularity. Jesse Jackson was so passionate about reinvigorating interest in the Black National Anthem, he reportedly elevated Weston’s arrangement as the gold standard and encouraged local radio stations to play it.

Should a song that threads the Black experience be communal domain? Is it separatist in a country that has never been invested in unity? A champion for the history and culture of African Americans, Johnson himself identified “Lift Every Voice and Sing” as the Negro National Hymn, honored that it resonated so deeply among the people he committed his life to loving and lifting. But it’s possible he recognized its ability to rally and unify others too.

“Johnson was the epitome of class and excellence, a global person, but as a well-informed citizen even back in his day, he knew that this song was larger than us. He knew it had international appeal because people around the globe were asking him if they could sing the song,” says Askew, himself passionate about the hymn’s mass appeal. “I mean, this song went everywhere because he went everywhere. It doesn't diminish Black folks because we deserve to sing a song that speaks to our experiences, but it just joins other people in a human struggle. We have to think of ourselves in a global sense.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/01/ab/01abe75c-def8-417c-88d6-284623139406/mobile_voice.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/c7/fdc7b4fa-5ee4-4507-ab99-f940c352dee5/music_social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/janelle.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/janelle.png)