Why Can’t We Turn Our Eyes Away From the Grotesque and Macabre?

Alexander Gardner’s photographs of Civil War corpses were among the first to play to the uncomfortable attraction humans have for shocking images

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6a/1a/6a1a913e-61af-4c91-8244-2e64ff0cc11e/home-of-a-rebel-sharpshooter_exh-ag-84-for-web.jpg)

In recent years, the public has been besieged by imagery of shootings, executions, kidnappings and all manner of crime, disseminated with ease thanks to the proliferation of smart phones, body cameras and the surveillance state. This week's shooting of two news reporters in Roanoke, Virginia, captured once on live television by the slain camerman, and then again by the gunman, who took video as he aimed and fired, adding an extra layer of horror to the violence. Through the killer's lens, we are looking through his gunsights and the effect is profoundly disturbing.

And we cannot look away. Like drivers passing the scene of an accident, our heads turn. We are inescapably drawn to disasters and especially the moment of death.

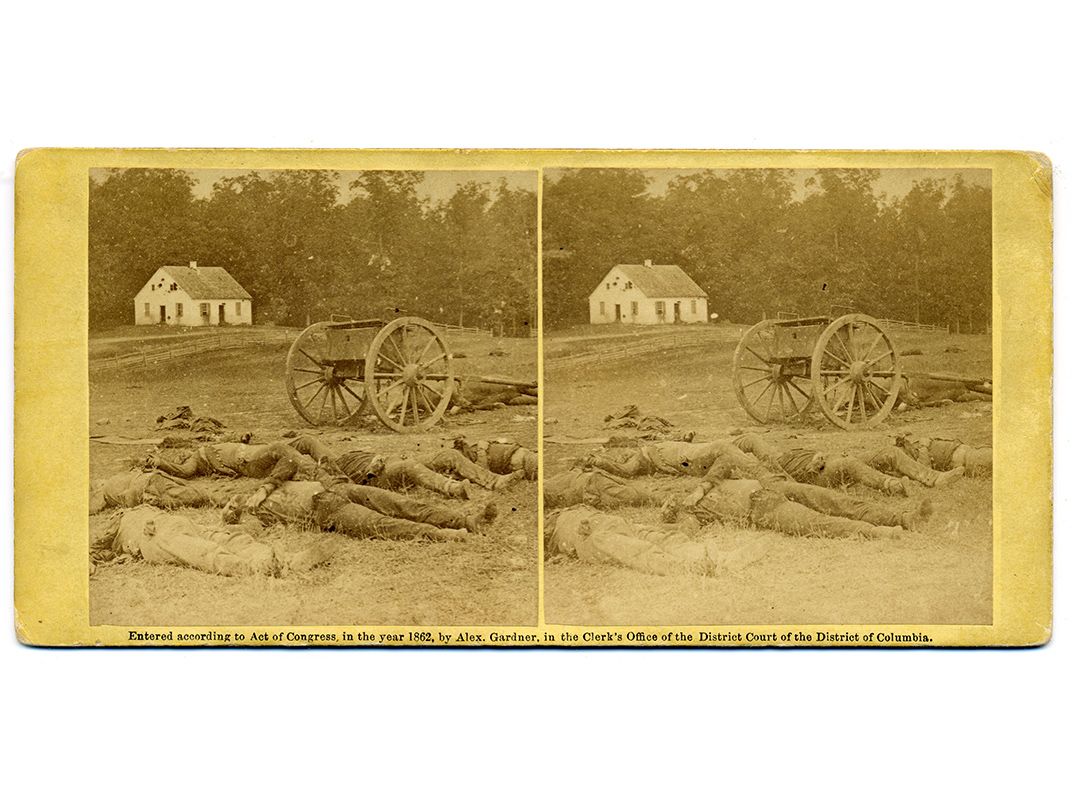

What now saturates our culture can be traced back to the advent of photography in the 19th century and especially to the work of Alexander Gardner during the Civil War. Gardner took his camera and darkroom out to the battlefields and created a visual record of the bodies and blasted landscapes of modern war.

Once disseminated, these shocking photographs contributed to vast changes in the society and culture of the United States, not least by breaking down the restriction over what it was permissible or proper to be seen. In this expansion of the visual field, Gardner’s camera helped usher in the modern world, so do we live with the moral and aesthetic consequences of the world that the camera created.

In the fall of 1862, Alexander Gardner, scenting a commercial opportunity, took his camera out to a battlefield near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and made the photographs that became known as The Dead at Antietam. Displayed to the public, and available for purchase at Mathew Brady’s Manhattan gallery (Gardner worked for Brady at the time), their effect was electrifying.

The New York Times wrote that the photographs had a “terrible distinctness” and that they brought the sobering, tragic reality of war home to the north. The emphasis was clearly on the documentary truth of the photographs and how that truth then impacted Northern culture, including not just its art and literature, but its emotions and habits of feeling. Historians from Edmund Wilson to Drew Gilpin Faust have charted the way that the Civil War was a watershed in the transformation in American culture, in everything from the way we write to mourning rituals.

Gardner’s photographs, by bringing the war home, clearly played a role in this transformation to what we can loosely call Modernism.

Yet it would be an error to cite Gardner’s photographs solely for their sobering effect on Victorian American culture and art; their impact on high culture, as it were. The photographs were also the beginnings of the visual macabre that has become a staple of popular and underground culture to this day. The photographs, as part of their association with magic, appealed to the sensations, including the psychological appeal of the macabre, the grotesque, and the uncanny.

Gardner’s photographs of blasted corpses, human and animal, elicited not just a rational response about the reality of modern warfare but pictured what had been forbidden or kept from view.

The photographs were transgressive, not just in the sense that combat fatalities could damage morale (the U.S. government still assiduously censors pictures of troops killed in action—coffins are only permitted to be shown when the family of the deceased consents or at a military funeral) but because they were psychologically appealing to large sections of the public. People wanted—and still want—to be shocked.

When Gardner dragged a Confederate corpse at Gettysburg out of the burial line and artfully arranged the body into a tableau about the dead Rebel sharpshooter, he was creating a melodramatic storyline that would be instantly familiar to an American audience steeped in the popular literature of the Gothic, of Poe and even of dark fairy tales. Even the rocky landscape and the enclosed cranny was redolent of Gothic architecture.

In positioning the corpse in a rocky nook at Devil’s Den, Gardner was psychologically indicating how a seemingly safe haven could suddenly be transformed into the site of violent death.

No one was safe, even in their home, and the title of the piece "A Rebel Sharpshooter’s Last Sleep" was, perhaps unintentionally, an ironic comment on Victorian propriety since the photograph made palpable the capricious and sudden death of soldiers on the battlefield. Yet this horror could still be managed by fitting it into familiar cultural formats.

After Gettysburg, Gardner was trying to organize the audience’s response, both intellectually and emotionally, to these harrowing images. Intellectually and figuratively in his arrangement of the corpse, Gardner was trying to compartmentalize reaction in familiar terms even as the reality of the casualties at Gettysburg made that task impossible.

The genie was out of the bottle.

Since Gardner left no written records, we don’t know how he responded to the public’s reaction to his Antietam photographs; the pictures did, however, create enough of a sensation and a marketing opportunity that they enabled Gardner to break away from Brady and set up his own business in Washington.

But there is another, less easily measured, reaction to the casualty photographs that takes them beyond rationality and connects them with our own age: this is the simple visceral appeal of shocking images: the trench full of corpses in Bloody Lane; the dead horse; the bodies strewn across a field at Gettysburg; the whole furious carnival of modern warfare.

What is uncomfortable to us is that it is likely that a sizeable portion of Gardner’s audience, then and now, was excited by the casualty photographs in ways that are difficult, even today, to explain except as part of human psychology’s attraction to the forbidden or the unseen.

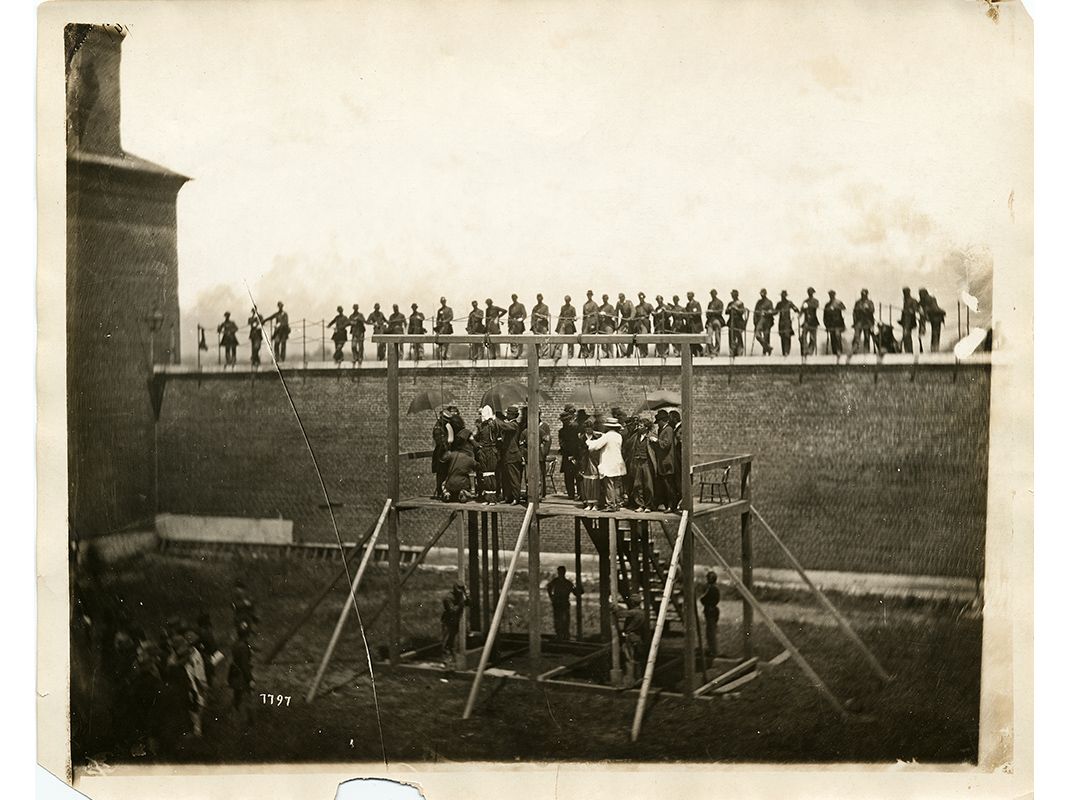

The photographs are sensational—in the original usage of the word. This atmosphere of visceral attraction also surrounds Gardner’s photographs of the execution of the Lincoln conspirators. Gardner had exclusive rights to photograph the executions and his series of images shows the ritual of official death from the reading of the death sentences to the bodies swinging beneath the gallows.

Rationally, the photographs were news and they also were an official record that justice had been done—and was documented for a public excluded from the hangings for security purposes. All this was done in the name of the majesty of the law and the nation, but the execution was also designed to be a visual spectacular, a virtuoso example of the executioner’s art with all four conspirators dropping simultaneously through the traps.

So the photographic evidence exists at several different levels of intention. Like the battle casualty photographs, they also exist on a sub-rational level in which the viewer, because of Gardner’s high camera perspective both distant and looking down on the gallows, is positioned as a voyeur of a thrilling and macabre event. As the trap doors of the gallows tripped open, the conspirators fell, and the camera’s shutter clicked capturing, in Gardner’s photographs, the moment of death in a way that combines documentary fact with sensational allure.

The seemingly objective technique of photography has a psychological, one can even say magical, impact that transcends the camera’s mechanism and is located instead in the complicated mind of the viewer. Photography vastly increased our field of vision, giving the audience access to what had been hidden, repressed, or thought to be taboo. From what the camera’s eye pitilessly records, we cannot turn away.

The exhibition “Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-1872,” curated by David C. Ward opens September 18, 2015 at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. The show will be on view through March 13, 2016.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)