Why the Dinosaurs Could Have Had a Chance of Surviving the Asteroid Strike

A new study suggests it wasn’t just the asteroid that killed the dinos, but that other factors weakened their ability to survive it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/38/6b38b42c-160d-428a-a68e-886b234edc00/dino_skeleton.jpg)

Long before a massive asteroid slammed into the earth and wiped out the dinosaurs, something was amiss in their world. The diversity of species was already waning. Had that not been the case—had the asteroid struck during a period of greater diversity—the dinosaurs might have survived the impact, and the world might look very different today.

Sixty-five million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous period, the fossil record shows that non-avian dinosaurs suddenly disappeared, and for decades, scientists have been trying to determine exactly how and why. They’ve come to agree that the impact of a 10km-wide asteroid slamming into what is now the Yucatan Peninsula played a major role, but debate has centered around whether that event was the sole cause of the mass extinction, or whether other contributing factors played a role. Those factors, however, have been hard to pin down, until now.

A study published today in Biological Reviews points to a very specific ecological shift taking place at the time the asteroid hit. The authors of the study believe that shift could have caused enough vulnerability among dinosaur populations to push them over the edge in the face of such a cataclysmic event.

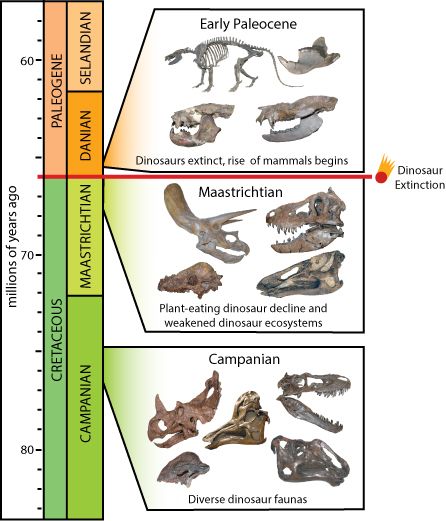

“There are probably more dinosaurs around at the end of the Cretaceous than there are at any other time,” say palaeontologist Matthew Carrano from the National Museum of Natural History. A co-author on the study, Carrano and his colleagues reviewed the most recent data available on dinosaurs around the time of the extinction in an attempt to make sense of what was going on. A clear pattern emerged. Although dinosaur numbers were solid at the time the asteroid hit, their diversity had been declining for a million years or so, especially among the very large herbivores such as the ceratops and the hadrosaurs.

“It’s not a very big drop in diversity, maybe just ten percent,” Carrano says. “But what might been going on is that the kind of dinosaurs that are having trouble are important dinosaurs in terms of ecology.” Plant eating species are a key part of the ecosystem because they’re the first step in converting energy from plants into food for all other animals on the planet.

The impact of the asteroid would have been devastating as it struck the earth with a force equivalent to 100,000 billion tons of TNT. It would have generated an earthquake one thousand times greater than anything ever recorded. Mega tsunamis would have followed and wildfires would have raged for years. A recent study also provides evidence of an “impact winter” that rapidly followed as dust and aerosols ejected into the stratosphere blocked the sun.

Cataclysmic indeed, but that alone may not have been enough to cause a mass extinction of more than half the species on Earth. Similar asteroids have hit the earth and not caused mass extinctions. So the question is, why was this one so different?

At the end of the Cretaceous, Earth had been in a very active volcanic period that would have led to dramatic environmental and climatic changes—volcanic gases such as carbon dioxide and sulphur dioxide would have led to global warming and acid rain. It has previously been suggested that those changes might have led to a decline in the dinosaur populations, weakening them to the point that they could not have survived the aftermath of the asteroid. The thing is, 65 million years ago, dinosaurs were in their heyday.

But says Carrano, if plant-eating dinos were having trouble, "the whole ecosystem gets a little bit shaky.” Perhaps the environmental changes caused by volcanic activity were affecting herbivorous dinosaurs, or maybe some other factor was involved. Carrano says these are questions for further study. But whatever caused the decline in diversity would have made herbivorous dinosaurs less resilient in a cataclysmic event. If the aftermath of the asteroid resulted in their demise, it would have had ripple effects throughout the globe.

The study focused primarily on the fossil record in North America, but there are other places around the world where Carrano says they should look to confirm this pattern of declining herbivore diversity. Places like Spain, Southern France, China, and possibly Argentina, may provide more proof and further clues.

In the meantime, Carrano is confident they’re getting closer to understanding what caused the dinosaurs to disappear. He says neither event on its own—the impact of the asteroid or the changes in herbivore diversity—would have led to the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period. But together, they formed the perfect storm. “The answer to the question ‘was it the asteroid?’ is ‘Yes . . . but.’ And the ‘but’ is just as important as the ‘yes’.”