Why Elaine de Kooning’s Portrait of JFK Broke All the Rules

After the assassination, the grief-stricken artist painted the president’s image obsessively; finally saying she caught only “a glimpse” of him

:focal(3783x482:3784x483)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/ff/fcff2aeb-1382-4991-8b67-bac7c012e108/gettyimages-159726542.jpg)

When artist Elaine de Kooning produced a painting for the Harry S. Truman Library, she said it was “not a portrait of John F. Kennedy but a glimpse.” Less than two years after John F. Kennedy’s assassination abruptly stole him from the nation, she said: “President Kennedy was never still. He slipped by us.”

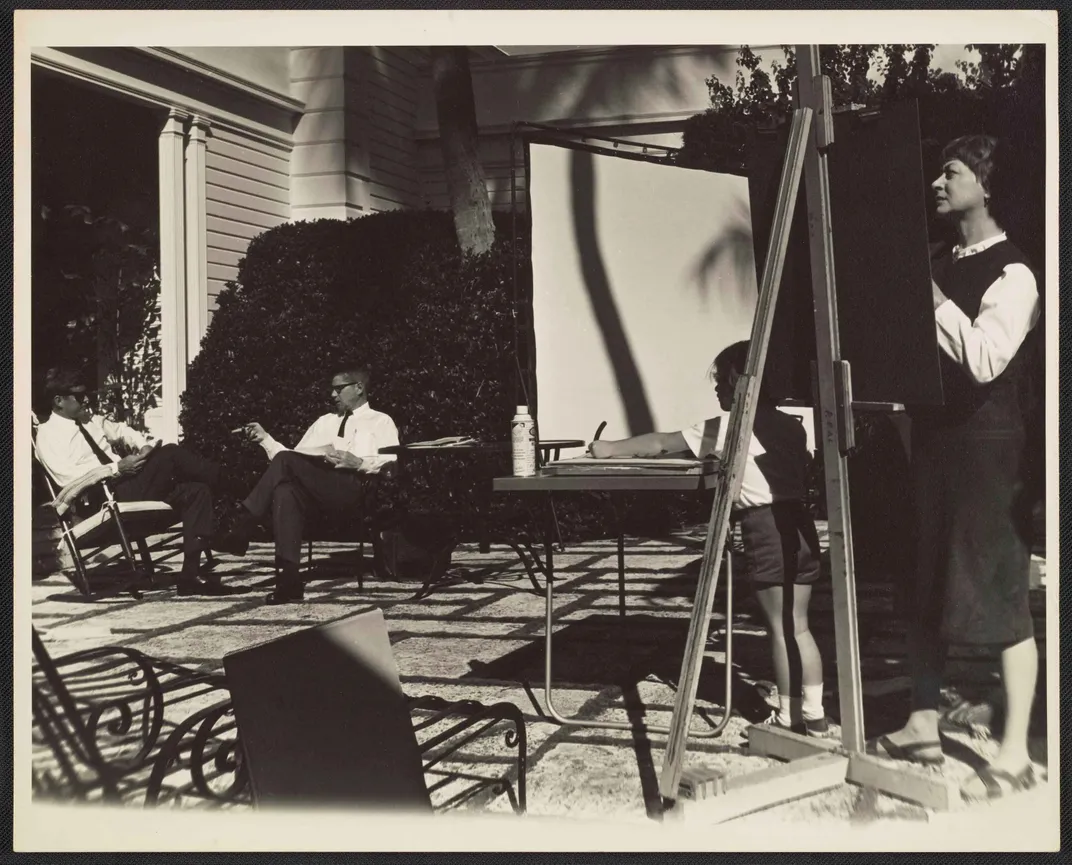

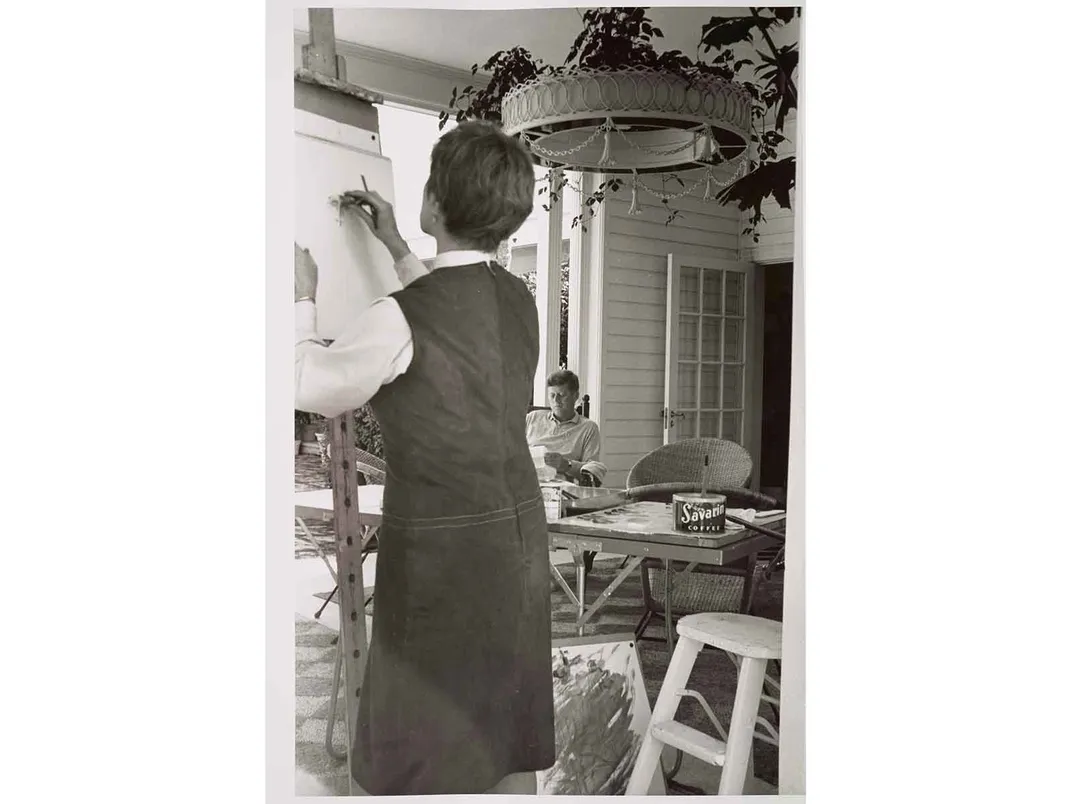

De Kooning had been commissioned to paint JFK in 1962, and she spent several sessions with him in Palm Beach, beginning on December 28, 1962. At the time she said she preferred for her subjects to sit still, but Kennedy was constantly surrounded by activity. Her job was even more challenging because “every day he would look just a little bit different to her. His likeness was elusive for her,” says the Smithsonian’s Brandon Brame Fortune, chief curator at the National Portrait Gallery, where one of the portraits in her body of work on JFK now resides. De Kooning’s portrait is the subject of a recent podcast, “Painting through a President’s Assassination,” in the museum’s Portraits series. Fortune and the museum’s director Kim Sajet discuss this most unusual portrait of a U.S. president. The work, Sajet says, generates a lot of written comments from visitors to the museum: They either love it or they hate it.

Listen to Brandon Fortune and the museum’s director Kim Sajet discuss this most unusual portrait of a U.S. president.

During that first meeting in Palm Beach, “she was taken with the golden quality of the air,” says Fortune. She called him “incandescent.” She worked to capture Kennedy’s essence through several sittings. One day, she painted alongside five-year-old Caroline Kennedy and lost her focus when the child squeezed out an entire tube of paint.

When she returned to New York in the winter, her mental image of JFK seemed to slip away, so she began watching Kennedy on TV and in the newspaper. She tried to marry “that incandescent person she had seen in person—that personal experience that she had of being close to the man—with the black-and-white images that the public would see in the newspaper and on television because in some ways, she thought that by capturing all of that in one series of paintings, she could somehow capture this elusive person,” Fortune says.

Over the coming months, she filled her studio workspace with studies of Kennedy—drawings and paintings of different sizes. Then, when she learned that he had been killed, she, like many Americans, spent four days in front of the TV watching as a nation in mourning laid a president to rest. Again, during those long, dark days, she tried to capture the man she had drawn so many times, but afterward, she could not paint at all for months. The crushing reality of his loss made it impossible. “She was just so moved by the erasure of this man from the world that she had to stop,” says Fortune. De Kooning made faceless bronze busts of Kennedy during this period. She called them “portraits of grief.”

“Painting had become completely identified with painting Kennedy,” de Kooning said. “For an entire year, I painted nothing else.” When Lee Harvey Oswald shot Kennedy, she was stopped in her tracks and saw no road forward. Over the course of 1964, a portion of her body of work on Kennedy was shown in New York, Philadelphia and Washington.

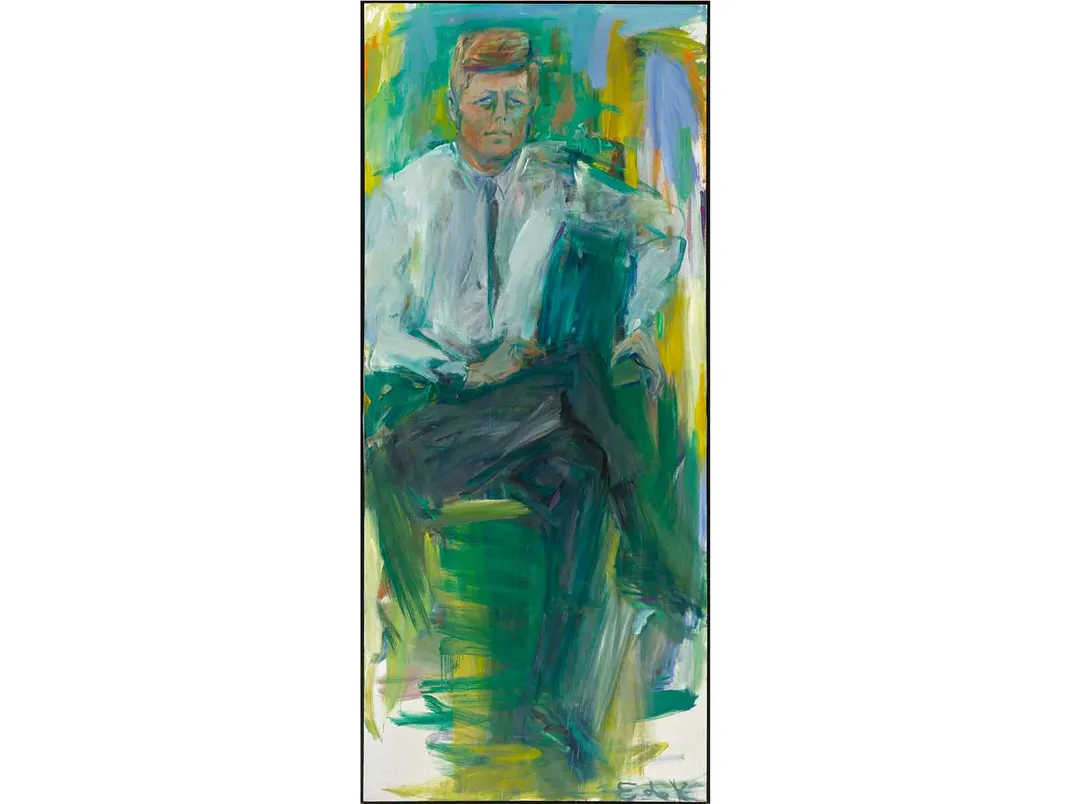

The commissioned body of work was unveiled at the Truman Library in 1965 and one, acquired in 1999, now hangs alongside other presidents in the National Portrait Gallery's "America's Presidents" exhibition.

De Kooning had clear ideas about her art. “The true portrait is full of reverence for the uniqueness for the human being portrayed,” she said. “Like falling in love, painting a portrait is the concentration on one particular person and no one else will do.” And as Fortune says, the artist fell in love with her most famous subject—JFK. After seeing him for the first time, Kennedy would become an obsession. She once even sculpted an image of him in wet sand on a beach. That Kennedy visage, like JFK himself, was short-lived. The high tide would wash it away.

She realized that her bright colors and heavy strokes had created a portrait that was probably out of place in the domain of Harry Truman, who preferred traditional art. At the unveiling, de Kooning said, “I hope that after a while, President Truman will get used to my portrait. I’m afraid it may take a bit of getting used to.” She told Truman, “This portrait is the culmination of a year of the hardest work I’ve ever done in my life, and I’ve always been a hard worker.”

In a way, de Kooning’s difficulty in painting after Kennedy’s assassination reflects an emotional fog that gripped the entire nation in the days, weeks, and, months after the youngest man elected president disappeared from public life suddenly and shockingly. Even Kennedy’s political opponents felt the disconcerting nature of his loss. Kennedy’s image still burns brightly in American memory, and for an artist seeking to capture that image with lively energy, the shock was understandingly paralyzing.

She enjoyed portraying those elements that made each human being special. “I’m enthralled by the gesture of silhouette, the instantaneous illumination that enables you to recognize your father or a friend three blocks away,” she said.

De Kooning, who was an art critic and teacher as well as an artist, died in 1989. She first met her future husband and teacher Willem de Kooning in 1938. He tutored her in the observational skills that he had acquired at a Dutch art school, and they married in 1943. Her first solo exhibitions were in the 1950s. She utilized the techniques of abstract expressionism made famous by Jackson Pollock, her husband, and many others who drew public attention in the years after World War II. These artists, who clustered in New York City, provided a wide variety of art. What they shared was an affinity for abstraction that produced unrealistic images and offered a wide margin for artistic expression. They often used huge canvases and different forms of paint. De Kooning was pleased that the Kennedy White House approved of her selection to paint him, perhaps because this new art form reflected the energy powering JFK’s New Frontier into a future that would take men to the moon.

She did not limit her work to portraits, but she made a point of using men as the subjects of most of her portraits. “Her depiction of male sexuality upended the more typical scenario of male artist and female subjects and challenged contemporary gender power dynamics and male privilege,” according to an article from TheArtStory.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/f7/65f78c88-3385-43f2-ab11-03983c5649a6/jfkyellow.jpg)

The Assassination of John F. Kennedy: Political Trauma and American Memory (Critical Moments in American History)

In The Assassination of John F. Kennedy: Political Trauma and American Memory, Alice George traces the events of Kennedy’s assassination and Lyndon B. Johnson’s subsequent ascension to the presidency. Drawing on newspaper articles, political speeches, letters, and diaries, George critically re-examines the event of JFK’s death and its persistent political and cultural legacy.

Her work has had a somewhat revolutionary impact at the National Portrait Gallery. The presidents who came before Kennedy are pictured formally in the “America’s Presidents” exhibit, a panoply of one dark-suited man after another.

One in De Kooning's series is a large, full-length painting filled with bold green and gold to reflect Kennedy’s dynamism. “It’s a riot of color and motion,” says Sajet. At the same time, the painting seems to convey Kennedy’s chronic back pain as he seems to balance his weight on the arm of the chair and appears ready to move, Fortune and Sajet agree.

His portrait “opened the door to all kinds of representations of the president that came afterward,” says Sajet. Some later leaders have appeared less formally and more colorfully. For instance, George W. Bush appears in casual attire, wearing neither a jacket or tie. Barack Obama wears a jacket as he sits before a background that is bursting with vibrant hues.

When she takes museum visitors to see “America’s Presidents,” Fortune says that “people sense the energy” of Kennedy’s portrait, and they often photograph it. “They want to capture all of that energy and take it away with them.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)