Why Elaine de Kooning Sacrificed Her Own Amazing Career for Her More-Famous Husband’s

The free-thinking Abstract Expressionist, even while in her partner’s shadow, captured an era with skill and élan

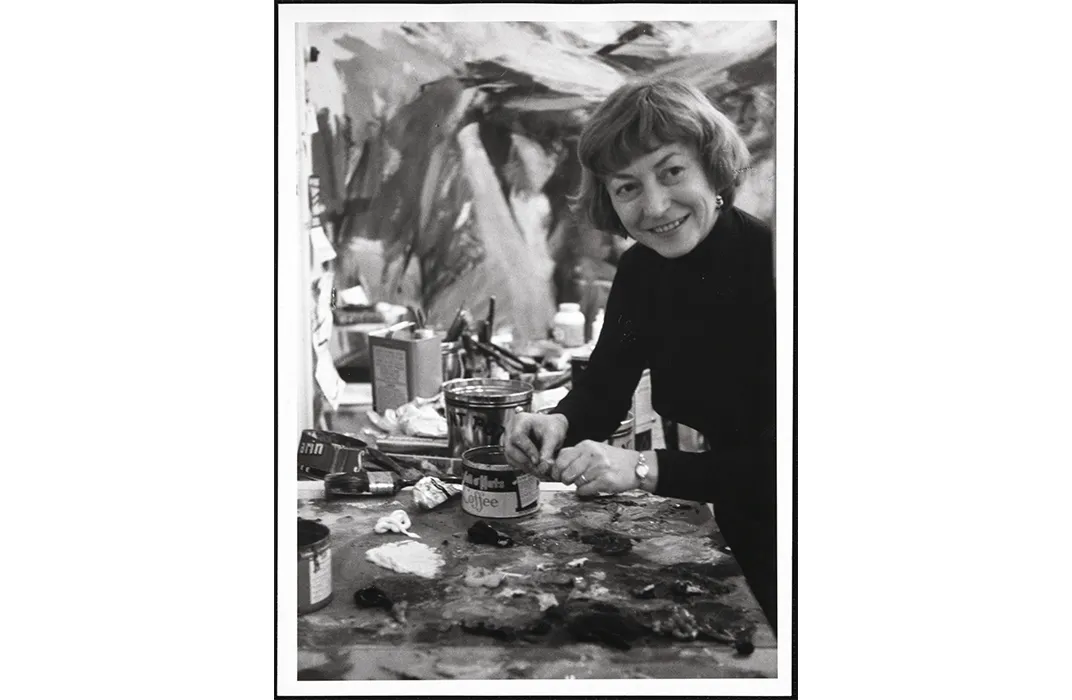

Elaine de Kooning was probably born 30 years too early. The New York painter, who died in 1989 at age 70, had a surfeit of talents. She was both a gifted figurative painter and a committed Abstract Expressionist, as was seen at a 2015 exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. She was also both femme fatale and proto-feminist, a free thinker, a writer, a respected critic, a popular friend and beloved teacher.

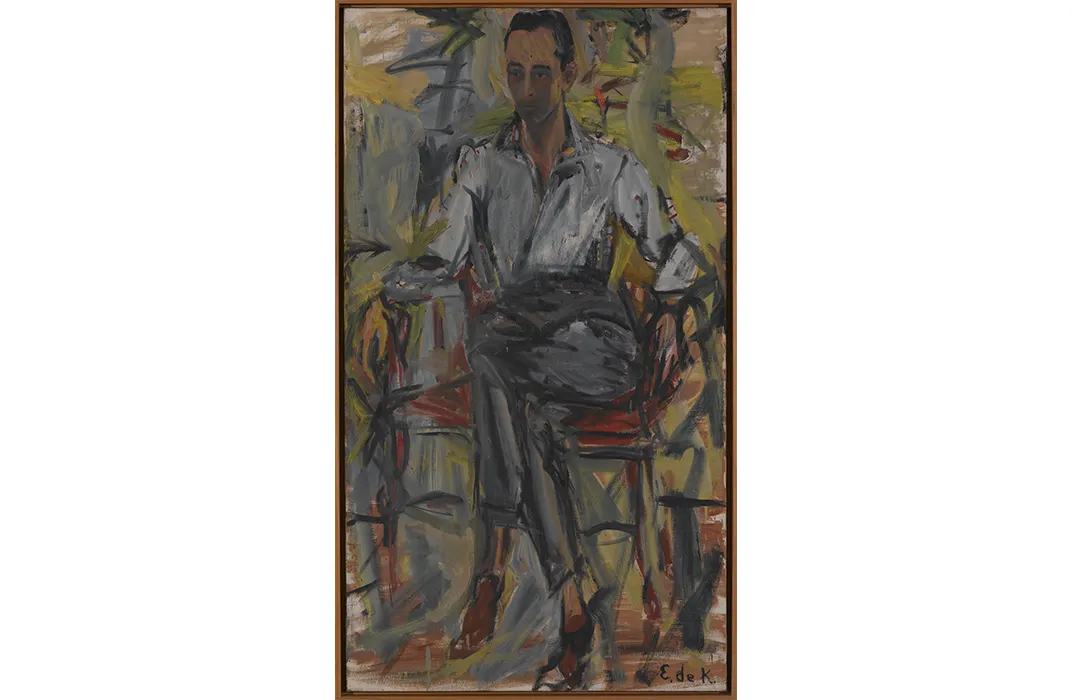

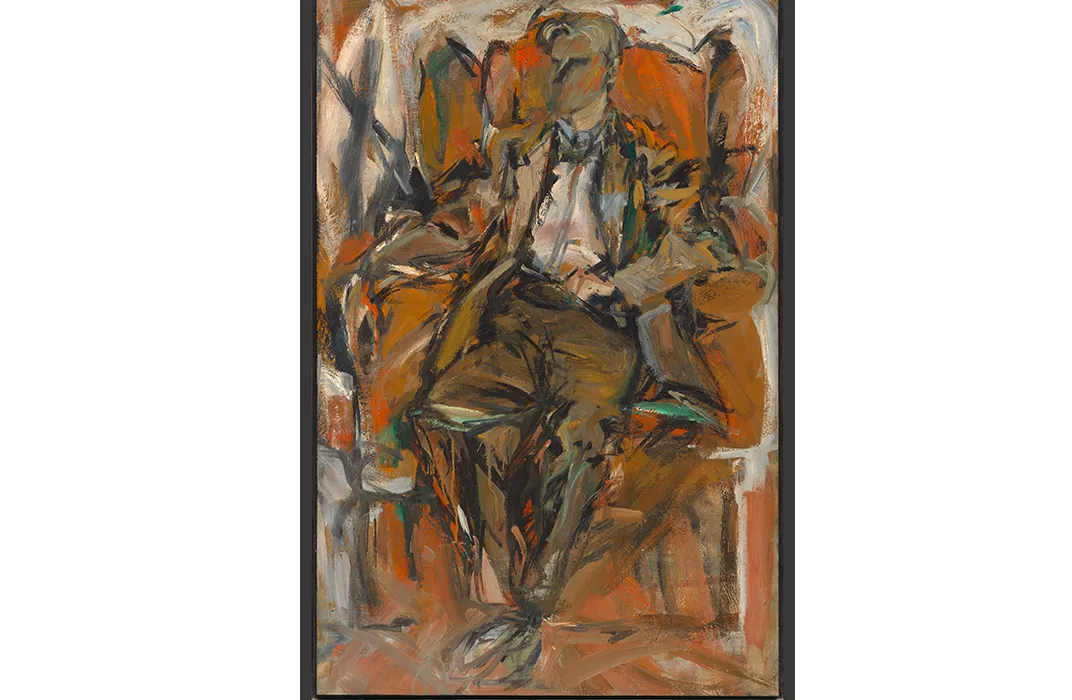

The show, the first major exhibition in 20 years devoted to Elaine de Kooning’s portraits, proves how skilled she was as a draughtsman—a third of the show is comprised of drawings—and how she reinvented the modern portrait by using figuration with an Abstract Expressionist vocabulary. “She wasn’t doing pure abstraction very much,” says the show's curator Brandon Brame Fortune. “She wanted painting and abstract qualities to merge with the figures.”

A film clip of her in the studio shows how quickly she could capture a person’s likeness and how articulate she was—albeit with a strong New York accent—about the process. With a fast, deft sketch of the subject’s most prominent features, she then overlays slashes of vivid, colorful paint in all directions, in and outside the lines, and the image emerges with a jazzy energy. One wonders if she would not have been better known as a painter today if she had kept her maiden name and/or had not married Willem de Kooning, the leading Abstract Expressionist of the 20th century….

The aim of the exhibition is “to begin the process of reassessing her career and her impact on art in New York,” Kim Sajet, the museum's director, writes in the catalog.

In that sense, the show is successful. A new image of Elaine de Kooning is emerging.

Born in 1918, Elaine Fried grew up the eldest of four in a modest Brooklyn home, with an Irish Catholic mother and a Protestant father. Her mother began taking her to the Metropolitan Museum at age 5 and decorated her bedroom with reproductions of paintings by Raphael, Rembrandt and Élizabeth Vigée Le Brun. By age 8 she was drawing portraits of her classmates—and selling them. She was also physically fearless, taking ballet, playing baseball and hockey. Once she dove off a rooftop.

“She was a daredevil,” her old friend, the critic Hedda Stern, recalled.

And ambitious.

She wanted to be an artist, so she quit college and enrolled at the Leonardo da Vinci Art School, where she would draw up to ten hours a day. She also took classes at the American Artists’ School.

She was a striking young woman, not conventionally beautiful, but tall, slender, with an erect carriage and fine features. (She earned extra money modeling at art schools).

In 1938 a friend introduced her to Willem De Kooning, the Dutch painter who had arrived in New York (as a stowaway, after several attempts) in 1926. Apparently, it was love at first sight.

At 34, he was a compact, taciturn painter who spent hours at the easel, obsessed with his work. By all accounts they fell madly in love. Lee Hall, former president of the Rhode Island School of Design and dear friend of Elaine’s, wrote in her 1993 book Elaine and Bill: Portrait of a Marriage that Elaine “was gregarious, ebullient, flirtatious, talented and beautiful,” whereas Bill “was amiable but solitary, slow and deliberate in his work, and often gloomy.” She was already a “femme fatale,” according to the artist Will Barnet.

They couldn’t have been more different. She was social. He was anti-social.

In 1938, De Kooning began giving Elaine traditional drawing lessons. He was very strict. He would set up a simple still life and have her draw it. Then he would study her drawing, critique it, tear it up and tell her to start all over again.

“Elaine said many times that Willem de Kooning provided her with the best teaching she ever had and that the skills he taught her became the foundation for her confidence as a portrait painter,” Hall writes. Her early self-portraits, in the show, prove the truth of Hall’s conclusion.

As Willem de Kooning started to be adulated by his peers, he and Elaine would go out together, to friends’ apartments and to Cedar’s Tavern, a dive bar in Greenwich Village popular among artists like Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner and Larry Rivers. Most artists in the Village were dirt poor then, so there was real camaraderie and little competition. The de Koonings were known to discuss art theory for hours on end. Elaine was belle of the ball, always the center of attention.

“She knew so many people,” said Fortune. “She was at the ‘red hot center’ of everything that was happening in New York.”

She did fine pencil drawings of De Kooning (one in the show's catalog, from 1939, is exquisite) and visited artists’ studios with him—his friends included Ashille Gorky, David Smith, Franz Kline and Barnett Newman. Nothing intimidated her: she held her own in fierce debates about Abstract Expressionism and could drink with the best of them. Her keen intelligence was obvious, Hall notes.

In 1943 de Kooning and Elaine married and she, convinced he was a genius, started promoting his career, often by having affairs with—and making portraits of—people who could help: the critic Harold Rosenberg, the Art News editor Thomas B. Hess and the gallery owner Charles Egan. The portraits of all three are in the show.

At the same time, she contributed reviews to Art News regularly. (Hall writes, from the beginning she was “certain of her own ideas about the purposes of art criticism.”) Hess in turn championed Abstract Expressionism and carried enthusiastic reviews of Willem de Kooning’s work. Charles Egan mounted the first show of his paintings. (None sold and the de Koonings continued to live in poverty.)

Elaine painted people for fun, including members of her family, the dealer Leo Castelli, the writers Donald Barthelme and Frank O’Hara and the painters Alex Katz and Fairfield Porter (Porter said, “Drawing is her forte.”). (All are in the show.) She made a fine studio portrait of the dancer Merce Cunningham (whom she met one summer at Black Mountain College in North Carolina), which also is in the exhibition.

“For her, each person has a pose,” Fortune writes in the catalog. “The pose is the person.” It’s true; you would know Cunningham is a dancer just by his posture in her portrait.

Sajet adds: She studied each person “to find the characteristic pose that would define them.”

In 1957, Elaine and Willem de Kooning separated; they were drinking too much and having too many affairs to stay together. To support herself, she took on a series of short-term teaching jobs, at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, the University of California in Davis, at Carnegie Mellon, at Southampton College on Long Island, at the Cooper Union and Pratt in New York, at Yale, at RISDI in Rhode Island, the University of Georgia and the New York Studio School in Paris.

She loved to teach and her students loved her. Toni Ross, a New York ceramicist, who is the daughter of one of Elaine’s good friends, Courtney Ross, says that Elaine was the best mentor and critic she has ever had. “She would come to my studio when I wasn’t there and write encouraging critiques on paste-up notes for me to find later on,” Ross adds.

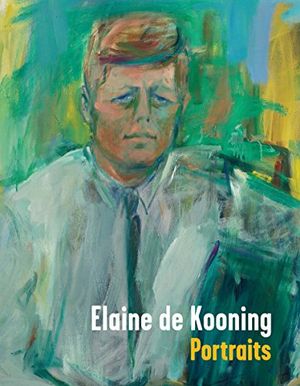

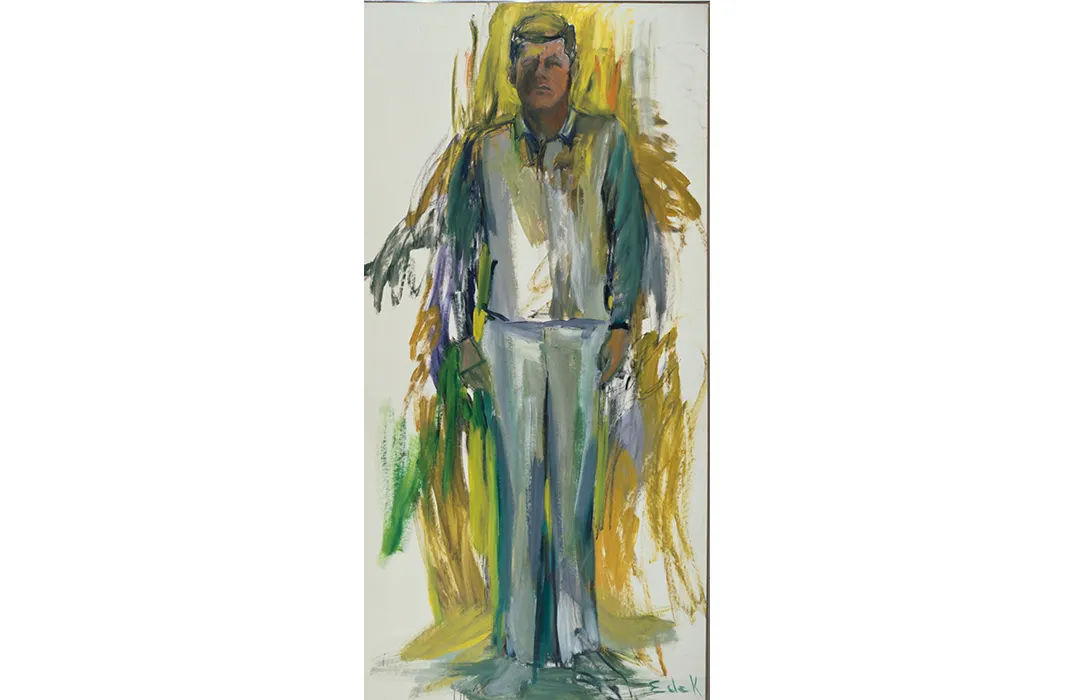

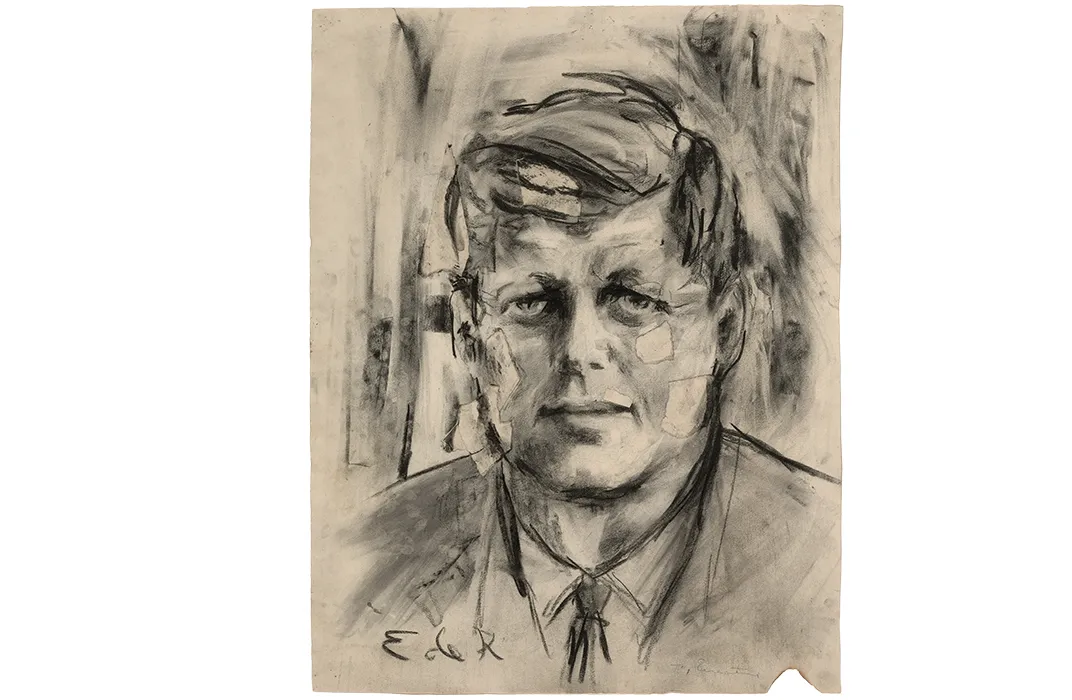

Her most important portrait commission was of President John F. Kennedy, for the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library. In December 1962 she went to the “Winter White House,” the Kennedy compound in Palm Beach, to spend a few days sketching the president as he worked with his staff on a terrace. She was hired because she represented the “new frontier” of painting (Abstract Expressionism) and she was quick. As she later wrote, “The first day I worked in pencil, pen and ink and charcoal. Charcoal’s great because it enables you to go like lightning. I kept several drawings going on at once. When he’d change his position I’d switch drawings…I kept jumping back and forth.” Many of these sketches and portraits of the president, standing, sitting, reading and relaxing, are in the exhibition.

She spent several months on the commission. She was obsessed with it.

Her thoughts are recorded in the catalog: “Beside my own intense, multiple impressions of him, I also had to contend with this ‘world image’ created by the endless newspaper photographs, TV appearances, caricatures. Realizing this, I began to collect hundreds of photographs torn from newspapers and magazines and never missed an opportunity to draw him when he appeared on TV… always striving for a composite image.”

Life Magazine commissioned Alfred Eisenstaedt to photograph Elaine in her studio, literally surrounded by dozens of sketches and paintings of the president. By September 1963, art scholar Simona Cupic writes in the catalog, “She finally reached the painting she had been searching for.”

Two months later, when the president was assassinated, Elaine was so upset she stopped painting for a year. Her commission is now at the Truman library, while a second version is in the JFK Library in Boston.

In 1976, now sober, Elaine reconciled with Willem de Kooning after he reached out to her. She bought a house near his in the Springs, on eastern Long Island, and took over the management of his studio. She also put him on Antabuse, so he would stop drinking. By then he was a world famous painter in need of her protection from distractions.

After decades of barely scraping by, Elaine had some money (from de Kooning) and was able to visit France a few times. She painted a series inspired by the Bacchus fountain in the Luxembourg Garden in Paris and another after the paintings she saw in the Lascaux caves. She continued to paint friends, like the artist Aristodemos Kaldis (several portraits of him are in the show). And she mentored young artists like Toni Ross.

Then, in the early 1980s, she lost one lung to cancer and subsequently suffered from severe emphysema. She died in 1989, right after the Fischbach Gallery did a show of her “cave paintings.” Willem de Kooning, stricken with dementia, continued to paint and outlived her another eight years.

Elaine de Kooning: Portraits was on view in 2015-2016 at the National Portrait Gallery.

Elaine de Kooning: Portraits

Elaine and Bill: Portrait of a Marriage : The Lives of Willem and Elaine De Kooning

de Kooning: An American Master

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wendy_new-1.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/f3/cbf32d8b-21ac-42e0-aedb-061ae48cc79c/elainedekooningselfportraitnpg9481web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f7/0e/f70e2fae-b39f-4422-a500-d8c5ce3e3f37/fairfieldporterek19web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/27/3a/273a5f70-e84f-4f9e-8abf-228119f0f7df/frankoharaweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/43/7c43cfd5-c643-4255-b672-4e2c70826449/haroldrosenbergnpg9414web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/0c/150c6265-fcad-4930-9947-576cb7cd86c5/robertdenirosrweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/53/c353f908-0491-47d6-b853-b159e08fd95f/jfkek31npg951web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/78/f9/78f93abc-3d3a-49ca-8b71-2e92bd50c6bf/johnfkennedyek32npg9975web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/39/86/39863334-3ffd-42e0-ba14-3e7f097f9821/jfkwatercoloramarilloek30web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wendy_new-1.jpeg)