Why Harriet Tubman’s Heroic Military Career Is Now Easier to Envision

The strong, youthful visage of the famed underground railroad conductor is the subject of the Portrait Gallery’s podcast “Portraits”

:focal(784x182:785x183)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a6/fc/a6fc8047-4d44-4e68-ba9c-13a61eae6488/tubmancloseup.jpg)

On June 1 and 2, 1863, Harriet Tubman made history—again. After escaping slavery in 1849 and subsequently rescuing more than 70 other slaves during her service as an Underground Railroad conductor, she became the first woman in American history to lead a military assault. The successful Combahee Ferry Raid freed more than 700 slaves in a chaotic scene.

After working for the Union army as a nurse and a spy, Tubman worked alongside Col. James Montgomery to plan and execute the mission along South Carolina’s Combahee River in South Carolina. Her spy work helped to catch the Confederate military off-guard and made it possible for a group of African American soldiers to overrun plantations, seizing or destroying valuable property.

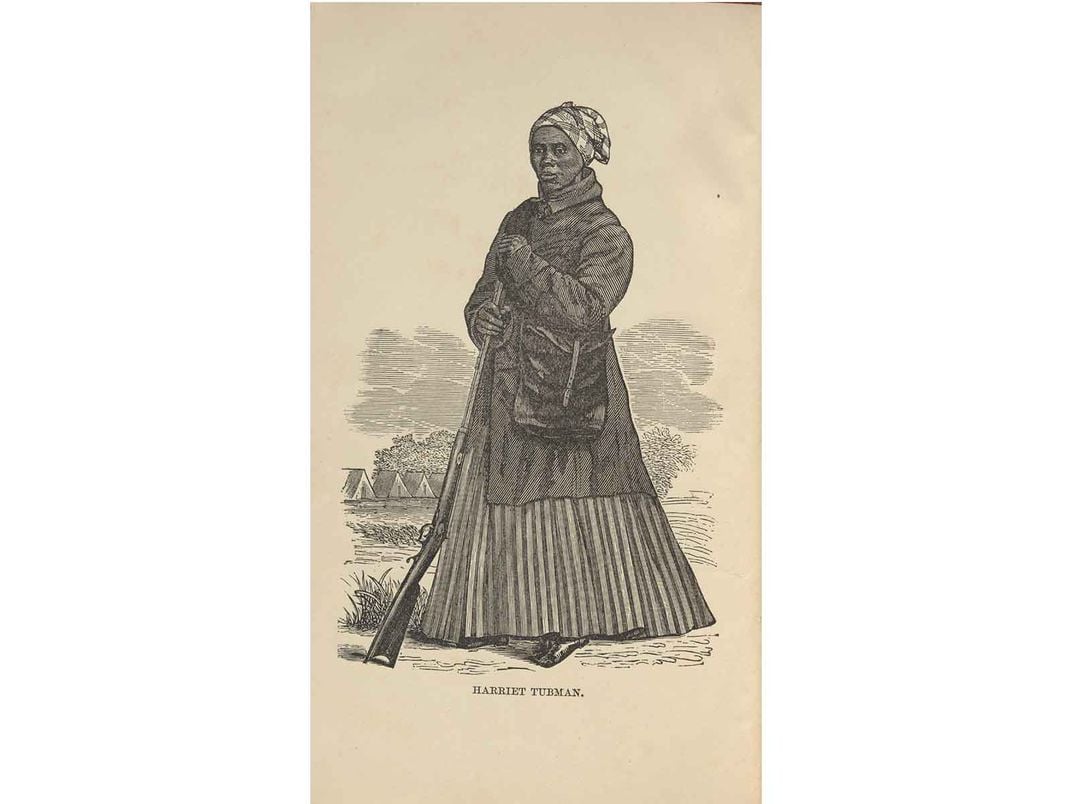

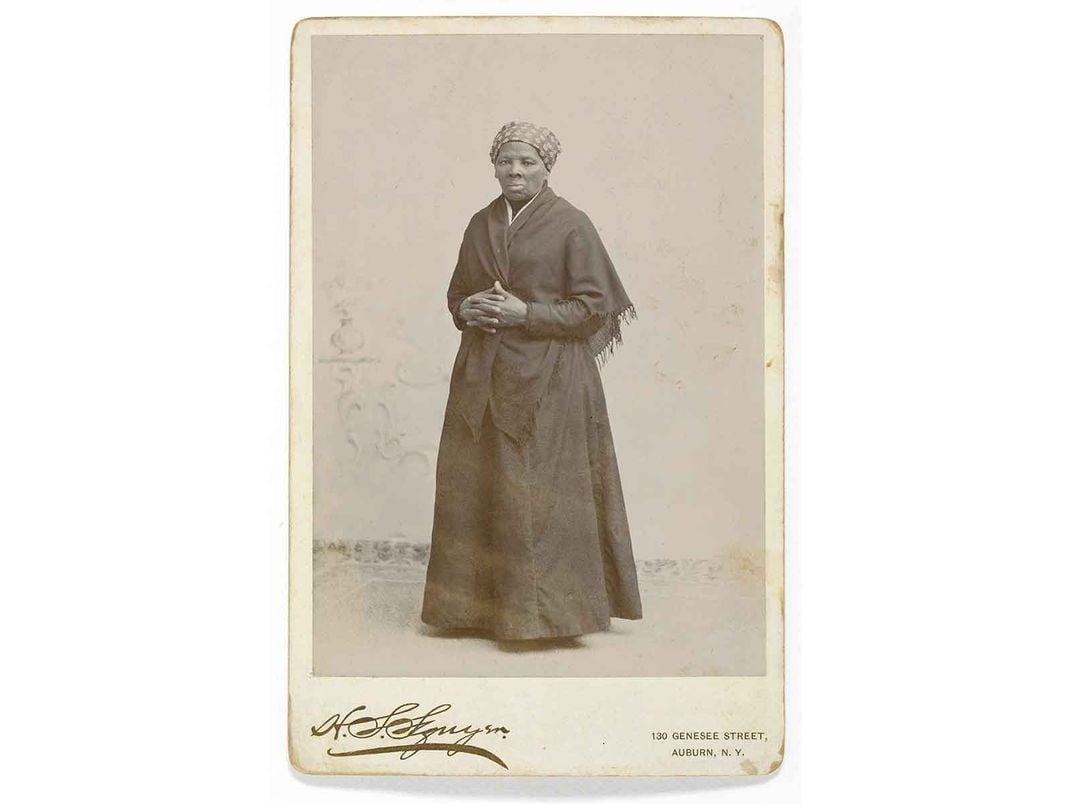

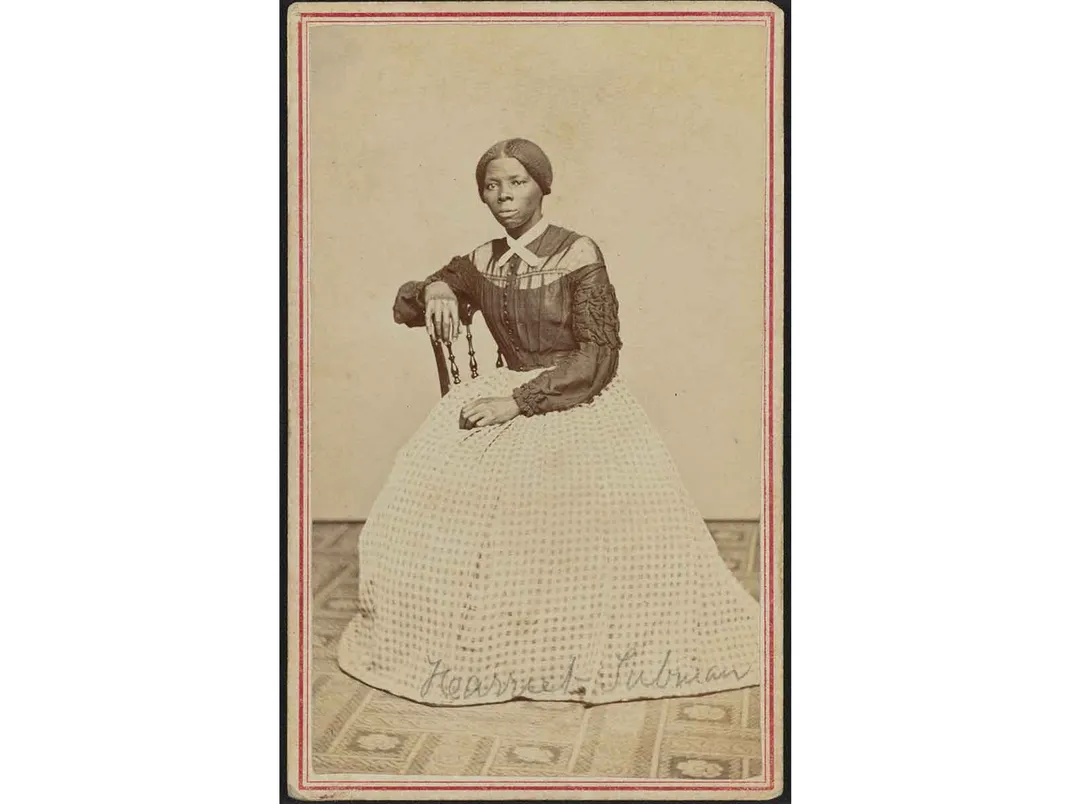

Over the years of her life, Tubman’s repeated efforts to free slaves had become known through press reports and a biography. However, until recently, it has been difficult to envision this petite-but-powerful heroine because the best-known Tubman photograph, taken in 1885, showed an elderly matron rather than the steadfast adventurer her history describes. “That’s been the tradition of viewing Harriet Tubman. She did all these daring things, but not having a visual image of her that would connect her experiences and what she did with that older woman was almost an oxymoron,” says Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden.

All of that changed in 2017 when the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture acquired a photograph of Tubman taken in 1868 or 1869, about five years after the Combahee raid. This image created excitement among historians who had longed to see a younger vision of Tubman. A recent episode of the National Portrait Gallery’s series of podcasts, Portraits, takes a closer look at the photograph’s impact on how we think about Tubman and the work she did.

Hayden recalls receiving the first news that the photograph existed. She got a phone call about the “first known photograph of Harriet Tubman,” and the person on the other end told her, “She’s YOUNG!” Tubman was about 45 when the photo was taken. When Hayden saw the image, she thought, “Oh my God, this is the woman that led troops and that was so forceful and that was a nurse and that did all these things and was so determined.” This image, long hidden in an album kept by a Quaker abolitionist and teacher, reveals the fierce woman heralded in historical accounts.

Listen to the National Portrait Gallery's "Portraits" podcast

"Growing Younger with Harriet Tubman," featuring Carla Hayden and Kasi Lemmons

Kasi Lemmons, who directed the 2019 film, Harriet, describes in the podcast her first reaction to this newly unearthed photo: “It’s not too much to say that I fell in love when I saw this picture of Harriet Tubman.” Lemmons was impressed by Tubman’s strength and by her grace. “She looks at home in her own skin. She’s looking at the camera—a very direct look. If you look carefully at her eyes, you see so much. You see sadness, and I see righteousness, and I see the power. You see incredible power in her eyes.”

Lemmons feels that the photo makes it possible to view Tubman’s life in a different light. “Her life lends itself inherently to an adventure story, but we couldn’t connect the image of her as an old, almost kindly looking, slightly stern old lady to the stories we knew of her heroics.” The photograph and a closer examination of Tubman’s history made it possible for her film to re-envision Tubman’s many rescues as something more than an example of great courage and determination. “It’s really a love story,” Lemmons says. “Harriet was motivated by love, love of her family, love for her husband. And then rescuing her people was connected to that, but almost incidental. It started with love of family.”

In many ways, Tubman’s story is a startling one. She triumphed as a black woman at a time when both African Americans and women had limited roles in a society dominated by white men. She also succeeded despite a disability: She suffered from seizures after being struck in the head as a teenager. In the wake of these blackouts, she sometimes reported having visions and speaking to God.

After the Civil War began, Massachusetts Governor John Andrew, an abolitionist, asked Tubman to help the Union Army, and she did, serving in several roles. Her knowledge of roots and herbs helped her while serving as a nurse to both soldiers and escaped slaves. The army also recruited her to serve as a scout and to build a spy ring in South Carolina. She developed contacts with slaves in the area, and in January 1863, she received $100 from the Secret Service to pay informants for critical details that could guide the Union Army’s operations. Often, her sources were water pilots, who traveled the area’s rivers and knew about enemy positions and troop movements.

The Union had captured Port Royal, South Carolina, in November 1861, giving them a foothold in enemy territory. Many plantation owners had fled the area, leaving their plantations to be run by overseers. Confederate forces had planted mines in the Combahee River, but Tubman and her allies were able to locate each one.

Following plans laid out by Montgomery and Tubman, three gunboats carrying about 150 soldiers, mostly from the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers, headed upstream on June 1, 1863 and safely avoided the mines. The next day, Montgomery ordered his men to destroy a pontoon bridge at Combahee Ferry. On neighboring plantations, soldiers confiscated supplies and burned much of what they couldn’t take with them.

After blowing their whistles to signal escaping slaves, the gunboats dispatched rowboats to pick up runaways. “I never saw such a sight,” Tubman later recalled. “Sometimes the women would come with twins hanging around their necks; it appears I never saw so many twins in my life; bags on their shoulders, baskets on their heads, and young ones tagging along behind, all loaded; pigs squealing, chickens screaming, young ones squealing.” It quickly became clear that there was not enough space on the rowboats to transport all of the slaves at once. Afraid of being left behind, some held onto the boats because they feared the gunboats wouldn’t wait for them. An officer asked Tubman to calm the slaves, so she stood on the bow of a boat and sang an abolitionist anthem:

Of all the whole creation in the east

or in the west

The glorious Yankee nation is the

greatest and the best

Come along! Come along!

don’t be alarmed.

The panicked fugitives began to shout “Glory!” in response to her song, and the rowboats were able to unload the first batch of escapees and return for the more. “I kept on singing until all were brought on board,” she later said. Of the 700 slaves who escaped, about 100 joined the Union Army.

After the raid, a reporter for the Wisconsin State Journal, who saw the gunboats’ return to their home base, wrote that a “black woman led the raid.” In Boston, Franklin B. Sanborn, a friend of Tubman and the editor of the Commonwealth, saw the story and rewrote it to name that black woman as Harriet Tubman. After returning from the raid, Tubman asked Sanborn to let it be “known to the ladies” that she needed “a bloomer dress” so that she could do her job without tripping. She had fallen during the slave rescue when she stepped on her dress while trying to corral an escapee’s pigs.

The operation had been carried out with minimal Confederate interference. Some troops were suffering from malaria, typhoid fever, or smallpox, so their superiors had moved many of them to locations that were less swampy and mosquito-ridden. Some Confederate soldiers did attempt to stop the raid, but only managed to shoot a single escaping slave. Confederate forces also turned artillery on the gunboats; nevertheless, none of the boats was hit. An official Confederate report recognized the fine intelligence gathered in advance by the Union forces: “The enemy seems to have been well posted as to the character and capacity of our troops and their small chance of encountering opposition, and to have been well guided by persons thoroughly acquainted with the river and the country.” Tubman and her band of informants had done their job well.

Tubman received only $200 for her service in the military and did not begin to get a pension until the 1890s—and that was for her husband’s military service, not her own. Nevertheless, when she died in 1913 at about 91, she was buried with full military honors. In 2003, a bill sponsored by Senator Hillary Clinton granted Tubman a full pension of $11,750, which was passed along to the Harriet Tubman Home, a historic site, in Auburn, New York

The U.S. Treasury Department plans to put Tubman’s image on the $20 bill in 2028. When the public was invited to submit choices for this honor in 2015, she was the most popular choice. The bill’s redesign had been scheduled to coincide with the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage—another of Tubman’s causes. However, the plan hit a snag. President Donald Trump opposed the change during the 2016 presidential campaign. In 2019 the New York Times reported that the introduction of the new currency was postponed. It is unclear whether the bill will feature an old familiar picture of an elderly Harriet Tubman or the earlier photo that captures her essence shortly after the Civil War ended.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)