Why History Museums Are Convening a ‘Civic Season’

History is complex, says the Smithsonian’s Chris Wilson; here’s how to empower citizens with the lessons it offers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/55/3255c437-3fbc-4e02-9532-5c34195e5942/jtss_images__6132011_204.jpg)

As the Smithsonian Institution joins with hundreds of other history organizations this summer to launch a “Civic Season” to engage the public on the complex nature of how we study history, it’s exciting to be at the forefront of that effort.

This year, the observation of Memorial Day took on a decidedly different tone. Because May 31 and June 1 also marked the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, the traditional acknowledgement of U.S. veterans who have died in service to the nation was also marked by conversations of the historical roots of racial injustice and how it manifests today. Many Americans found room in their commemorations to recognize victims of violence and those murdered a century ago when racist terrorists attacked and burned the Tulsa’s Black neighborhood of Greenwood to the ground.

This reinterpretation of one of America’s summer celebrations left me thinking about the way public historians teach about our past, and that what we remember and commemorate is always changing. Museums and public history organizations strive to use stories of the past to empower people toward creating a better future.

This motivation gets at why, this summer, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History is joining other U.S. museums to inaugurate the first Civic Season. The idea is to establish the period beginning with June 14, Flag Day through the Fourth of July, and includes Juneteenth and Pride Month, as a time of reflection about the past and for dreaming about a more equitable future.

Read More About the New Summer Tradition: 'Civic Season'

History is taking a place on the front burner of the national conversation. Scholars and educational organizations who focus on deep analysis of the past are unaccustomed to being this topical. They are certainly not used to being at the center of political and ideological battles that pit historical interpretations against one another.

Flashpoints include: The 1619 Project, named for the year when the first 20 enslaved Africans landed by ship in Virginia; the 19th-century phrase “Manifest Destiny,” as westward expansion came with the genocidal dispossession of Native peoples; the reconsideration of statues of Confederate soldiers in town squares; and the rethinking of the reputations of many of our Founding Fathers in the context of their participation in the brutality of slavery.

One thing that underpins the dissonance about “history” is a core misunderstanding of the practice of scholarship. “History is what trained historians do, a reasoned reconstruction of the past rooted in research; it tends to be critical and skeptical of human motive and action, and therefore more secular than what people commonly call memory,” argues David Blight, a historian at Yale University. “History can be read by or belong to everyone; it is more relative, and contingent on place, chronology, and scale.

Unfortunately, the public very often conflates history with memory. “If history is shared and secular, memory is often treated as a sacred set of absolute meanings and stories, possessed as the heritage or identity of a community,” writes Blight. “Memory is often owned, history interpreted. Memory is passed down through generations; history is revised. Memory often coalesces in objects, sites, and monuments; history seeks to understand contexts in all their complexity.”

The work historians do to produce an evidence-based picture of what happened in the past is often composed work, comfortable with complexity and rejecting of morals and lessons, while memory is about emotion and nostalgia. Much of the work in public history over the past 30 years has been in this space between history and nostalgia with a view toward finding common ground, with a hope and belief that better understanding of one another and multiple perspectives can bring about a more compassionate future.

At the museum, we have developed an active and dynamic visitor experience—creating a space alive with conversation that creates community between the museumgoers that come to us from all over the world.

One of the tools we use to redefine the museum into a space and experience is theatrical performance. I came to the Smithsonian after a long career at The Henry Ford in Dearborn, Michigan, where I had written and directed dozens of plays performed mostly in Greenfield Village, the outdoor history park, with actors reanimating these historic structures and spaces with scenes of the past. As my colleague Susan Evans McClure wrote in the journal Curator, we believed “this format of interactive performance can be used as a model to engage audiences and inspire conversation and reflection in museums.”

The first major program we developed that supported this model was the 2010 interactive play “Join the Student Sit-Ins,” staged at one of the iconic objects in the Smithsonian’s collection, the Greensboro Lunch Counter. This section of the lunch counter was from the F. W. Woolworth store in Greensboro, North Carolina, where on February 1, 1960, four Black college students at North Carolina A & T University began a legendary sit-in for racial justice.

When an object like the lunch counter is collected and displayed by the Smithsonian Institution, it takes on a mythic status. It risks becoming an icon where memory resides and complex history is unapparent. Much like the popular memory of the Civil Rights Movement itself, which has become according to historian Jeanne Theoharis a misleading fable devoid of controversy and nuance, the takeaway of most visitors to the lunch counter was “Wasn’t that courageous? They certainly did the right thing and I definitely would have been right there with them.”

But history tells us that most people, even most Black people, would not have been right there with them. The doubts and uncertainty around this new, radical and aggressive protest method were dangerous and possibly harmful. Even leaders like Martin Luther King were skeptical about some of the more aggressive direct action campaigns like the 1961 Freedom Rides.

We wanted to use performance and participation to complicate this experience and replace the assurance and moral certainty visitors brought to the object, with confusion and indecision. We wanted to find a way to replace the simplicity of the mythic memory of a peaceful protest everyone could agree with, and complicate it with the history of a radical attack on white supremacist society.

So instead of dramatizing the first day of the sit-in, we decided to re-create the training experience of the nonviolent direct action workshops like those Reverend James Lawson had begun in 1959 in Nashville where he taught Ghandian tactics to eventual movement leaders like John Lewis and Diane Nash.

These training sessions included role playing exercises where recruits would practice the conviction and tactics they needed to endure the taunts, threats and actual violence they would encounter on a real sit-in. We asked the assembled audience a simple question: “What’s wrong with segregation?” Our actor Xavier Carnegie played the character of a veteran of several sit-ins and a disciple of nonviolent direct action principles, reminding visitors that it was 1960, and segregation in private businesses was perfectly legal.

So, on what basis can we change that situation? Visitors invariably looked confused. “It’s not right.” “It’s not fair.” Our trainer would say he agreed with them, but then would reiterate that the law in 1960 didn’t support their feelings.

The audience often responded, “We should all be equal.”

“If you feel everyone should be treated the same how about this,” Carnegie would reply. “We could have two lunch counters, one for white people and one for people of color. The food would be the same, the prices equal. Is it ok that we segregate now?”

The audience would answer no, but were stumped when they were asked, “who says?”

One person might answer, “all men are created equal,” to which our trainer would ask where and when that phrase originated, who wrote it, and how many enslaved Black people did he own.

Another would point out that the Supreme Court stated “separate is not equal,” but our trainer would note that the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling applied to public schools and even in the year 1960, schools weren’t desegrated as Southern states employed “massive resistance” against the ruling. Once a historian in the audience spoke up and referenced the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment as the authority that said segregation shouldn’t exist, but the trainer would point out that if that 19th-century amendment was the ultimate authority, they wouldn’t be gathered together planning to risk their lives to defeat injustice.

As the stumped audience sat in uncomfortable silence considering the question of “who says,” a woman raised her hand and softly answered, “I do.”

The trainer pointed to her and asked the audience to note her answer as he asked her to repeat it. “I say we can’t have segregation.”

That was the answer he was looking for because that’s really what was at work during the Freedom Movement against racial injustice.

Individual people were deciding they wanted something different from their country. Never mind the law and precedent that was not on their side. Never mind the flowery language of the Declaration of Independence or mottoes like “Land of the Free” that were written by men who didn’t live up to their rhetoric. Never mind amendments and court rulings that went unenforced. Change began without any of that authority and only because thousands of individual people made choices to put their bodies on the line, using principled nonviolent direct action and not violence and brutality, to create the nation they thought should exist.

Through the familiar format of theater, we created learning communities in which visitors experience emotionally history as a series of acts by real people, not as an inevitable story written in a textbook or remembered as a simple fable. This emotional learning is powerful and we’ve heard countless times over the 13-year life of this program that such experiences stayed with visitors for years after a visit to the Smithsonian.

One of my colleagues, curator Fath Davis Ruffins, often says as we consider the public’s lack of comfort with the complexity of history and desire for morals and myths, “many things are true.”

If we can use Independence Day, a day to celebrate freedom and ideals, and Juneteenth, a day that shows despite promises and rhetoric, freedom must be seized by those who hope to be free, we can help people understand that history supports legitimate contradictory memories at the same time.

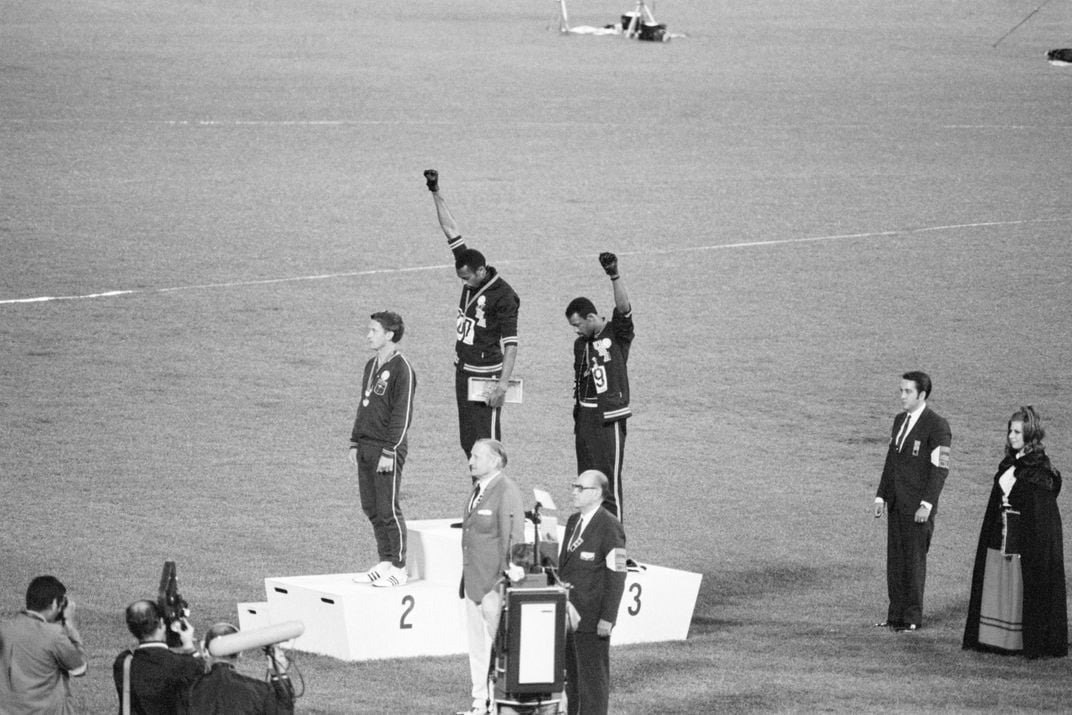

A museum that is the home to the Star-Spangled Banner can use history to show that many things are true and that history can legitimately inspire one person to remove their hat for the National Anthem, while leading another to kneel while it is being sung. We must help people be comfortable with that complexity, but even more to understand and respect others who take different meaning from the events of our shared past.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kegley140407Wilson0014.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kegley140407Wilson0014.jpg)