Why Louisa May Alcott’s ‘Little Women’ Endures

The author of a new book about the classic says the 19th-century novel contains life lessons for all, especially for boys

:focal(1154x651:1155x652)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/80/f180f190-6a9c-4a01-90f0-26020a6e3c2d/30527538.jpg)

When Louisa May Alcott lifted her pen after writing the last line of Little Women, she never would have believed that this piece of autobiographical fiction would remain in print throughout the 150 years after its September 30, 1868 publication. Alcott’s masterpiece is a 19th-century time capsule that still draws young readers and has spawned four movies, more than ten TV adaptations, a Broadway drama, a Broadway musical, an opera, a museum, a series of dolls, and countless stories and books built around the same characters. Earlier this year, PBS broadcast a two-night, three-hour Little Women film produced by the BBC. A modern retelling of the classic will arrive in theaters September 28, director Greta Gerwig is planning another film for late 2019.

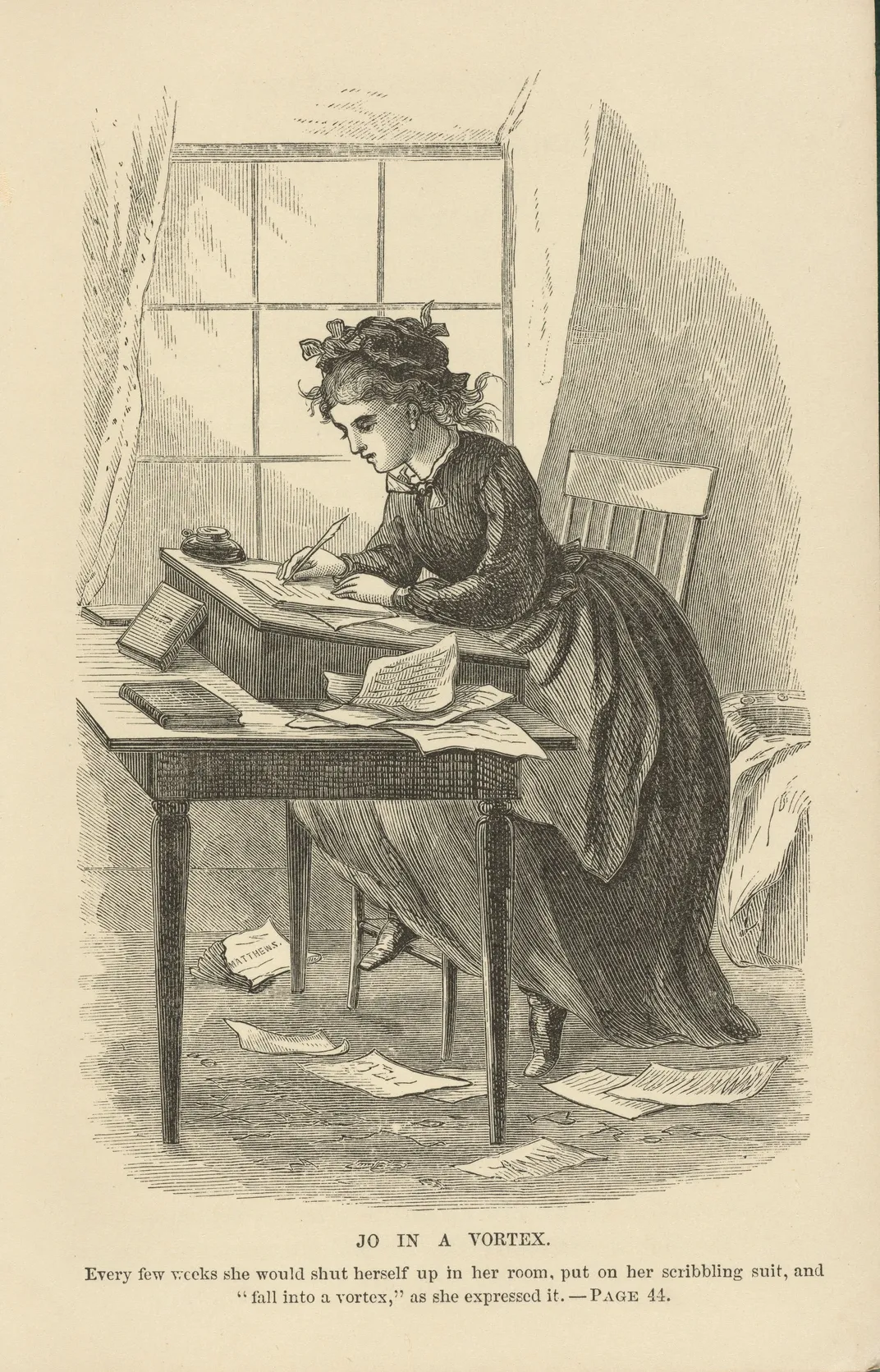

A new book by Anne Boyd Rioux—Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy—explores the cultural significance of Alcott’s most successful work. Rioux says she was surprised by “the incredibly widespread impact that the book has had on women writers, in particular.” Little Women’s most flamboyant character, the high-tempered and ambitious Jo March, is an aspiring author and an independent soul, much like Alcott. Her nascent feminism has touched many who have admired her challenges to societal norms while embracing its virtues. Over the years, Jo has fed the ambitions of writers as diverse as Gloria Steinem, Helen Keller, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Gertrude Stein, Danielle Steel, J.K. Rowling, Simone de Beauvoir and national Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith.

Little Women, which has never been out of print, follows the adventures of the four March sisters and their mother, “Marmee,” living in somewhat impoverished circumstances in a small Massachusetts town while their father is away during the Civil War. By the 1960s, Alcott's story had been translated into at least 50 languages. Today sales continue, after having found a home among Americans’ 100 most favorite books in 2014, and being ranked among Time’s top 100 young adult books of all time two years later.

At the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, a photograph of Alcott taken by George Kendall Warren between 1872 and 1874 in his Boston studio shows the author, her head bent in profile, reading from a sheaf of papers she holds in her hands. Little is known about the image but the museum’s curator of photographs Ann Shumard was able to determine the date range based on the studio address on the back of the photo.

Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why It Still Matters

Today, Anne Boyd Rioux sees the novel’s beating heart in Alcott’s portrayal of family resilience and her honest look at the struggles of girls growing into women. In gauging its current status, Rioux shows why Little Women remains a book with such power that people carry its characters and spirit throughout their lives.

A former daguerreotypist, Warren “was well-known for documenting the literary celebrities that were in the orbit of Boston as well as individuals who came through that city to lecture or appear publicly or visit their publishers,” Shumard says. “Picturing Alcott with papers in her hand—that really is a way of situating her as a woman of letters.” Alcott’s elaborate draping attire, according to Shumard, represents “what a respectable, well-brought-up woman would have worn to have her portrait made,” Shumard says.

When a publisher asked Alcott to write a book for girls, the already-published author procrastinated. “I think the thought of a girls’ book was stifling to her,” Rioux says. In fact, Alcott once commented that she “never liked girls or knew many except my sisters.” When she finally wrote the book, she composed it quickly and with little deliberation, basing the characters on her own family.

Little Women triumphed immediately, selling the initial run of 2,000 books in just days. The original publication represented the first 23 chapters of what would become a 47-chapter book. Soon, her publisher was shipping tens of thousands of books, so he ordered a second installment, which would complete the classic. “Spinning out her fantasies on paper, Louisa was transported, and liberated. Her imagination freed her to escape the confines of ordinary life to be flirtatious, scheming, materialistic, violent, rich, worldly, or a different gender,” writes Alcott’s biographer Harriet Reisen.

Little Women was not strictly for girls. Theodore Roosevelt, who was the very model of a manly man, admitted that “at the risk of being deemed effeminate,” he “worshipped” Little Women and its sequel, Little Men. At the end of the 19th century, Little Women appeared on a list of “the 20 best books for boys,” but in 2015, Charles McGrath of the New York Times confessed that as a child, he read Little Women in a brown paper wrapper to avoid taunts from other boys. Rioux says she understands that reading the novel and feeling like outsiders can be unsettling for boys, but she believes “that’s a great experience for them to have.”

Furthermore, “it’s a book that has had such widespread cultural ramifications, has ignited so many discussions over the years, and has had real world impacts on people’s lives and their perception of themselves and perception of each other and our culture,” says Rioux. She has found that Little Women is “a worldwide phenomenon” and “a story that has translated across time and space in a way that few books have.” Alcott’s decision to throw the spotlight on four different girls demonstrated to readers “that womanhood isn’t something you’re born with; it’s something that you learn and grow into,” Rioux says. “And you have the ability to pick and choose which parts of it you want.”

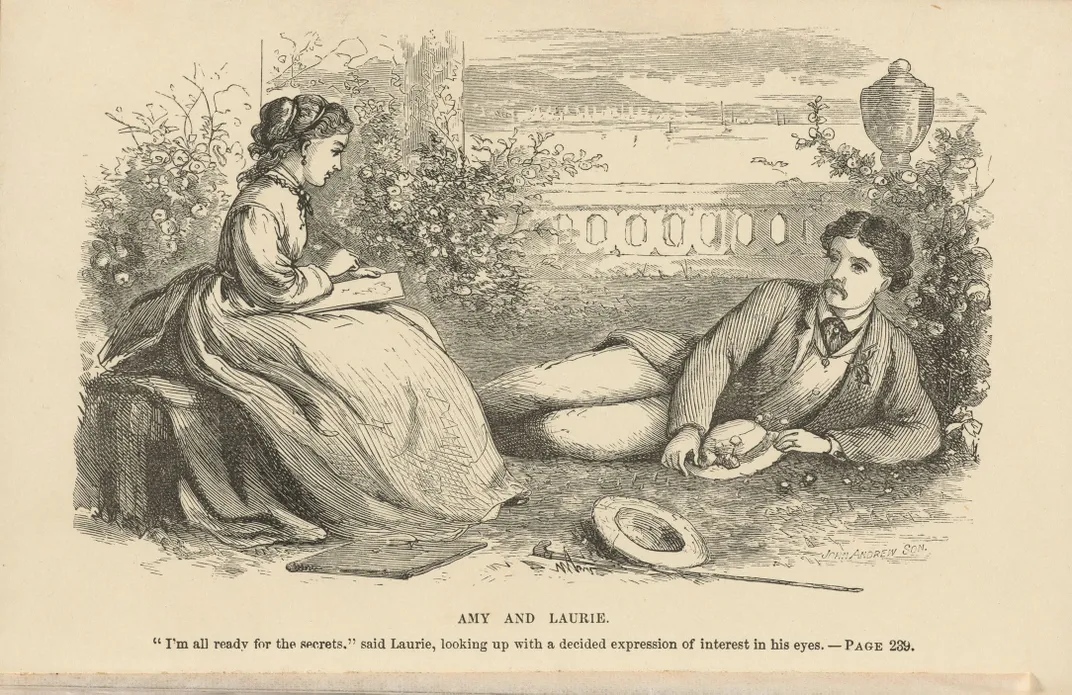

For many readers, the heart of the book’s second half was a simple question: Would Jo marry her charming neighbor, Laurie? Alcott had hoped to leave Jo a “literary spinster,” like herself; however, fans demanded that Jo marry. Alcott bowed to pressure but didn’t give her readers everything they wanted. Jo disappointed many 19th-century fans by rejecting Laurie’s marriage proposal in a scene made especially painful by her genuine affection for him. After denying Laurie, Jo wed a less obviously appealing older man. Faced with readers’ eagerness for a wedding, Alcott later said that she “didn’t dare to refuse & out of perversity went & made a funny match for her.” Equally to the dismay of 20th century feminists, the marriage caused Jo to abandon her writing career.

After the novel’s release, readers learned that Jo mirrored its author, while Alcott’s real-life sisters—Anna, Lizzie, and May—were models for the March sisters. What readers did not know was that unlike Jo, Alcott experienced an unstable family life. Her father Bronson was a Transcendentalist who rubbed shoulders with Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Although he encouraged his daughter’s writing, he believed working for money would violate his philosophy. Consequently, his wife and daughters labored to feed the family, which moved often. This may explain Mr. March’s small-but-exalted role in Little Women.

In Little Women, Alcott brought the quite different March girls to life by endowing each with assets and flaws. Beautiful Meg was vain and dreamed of riches; stubborn-but-talented Jo was prone to fits of temper; sweet, timid Beth wanted to spend adulthood at home; and often-selfish Amy yearned to be an artist. Pulitzer Prize-winning author John Matteson wrote in Eden’s Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father that what gave the second installment “its enduring power is that not one of the March sisters gets what she had once believed would make her happy.” Meg married a financially strapped man; Jo stopped writing; Beth suffered a lingering illness and died; and Amy abandoned her artistic dreams.

Initially, the book generated both literary and popular enthusiasm, but within two decades, fans remained ardent while elite support declined. Little Women sold well in Great Britain, and during the 19th century, it was translated into many languages, including French, Dutch, German, Swedish, Danish, Greek, Japanese and Russian. After its success, Alcott became a wealthy celebrity appalled by strangers who visited her Concord, Massachusetts, home. When she died in 1888, the New York Times wrote in a front-page obituary that “there is little in her writings which did not grow out of something that had actually occurred, and yet it is so colored with her imagination that it represents the universal life of childhood and youth.” Her home, Orchard House, became a museum in 1912, the same year Little Women premiered as a Broadway drama. A musical rendition reached Broadway in 2005.

Two now-lost silent films—one British, one American—emerged in 1917 and 1919. Katherine Hepburn starred as Jo in the first major film in 1933, and her performance remains the most indelible. A series of Little Women Madame Alexander dolls joined a host of other related products spurred by the film’s success. June Allyson became Jo in a 1949 film, and Winona Ryder tackled the role in 1994. Mark Adamo’s critically acclaimed opera debuted in 1998 and was broadcast by PBS in 2001.

In the 1970s and 1980s, feminists appreciated the book’s portrayal of gender as learned conduct rather than innate behavior. They also noted Alcott’s portrayal of the girls’ overworked mother, Marmee, who concedes, “I am angry nearly every day of my life, Jo, but I have learned not to show it.”

Despite feminist interest—or perhaps because of it—Rioux notes that the book began falling off school reading lists in the last half of the 2oth century.

It is no longer commonly read in U.S. schools, at least partly because it is seen as unappealing to boys. She believes this plays a role in depriving boys of the opportunity to understand girls’ lives. “I think that’s a real shame,” Rioux says, “and I think it has real world cultural consequences.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)