Some of America’s most amazing natural wonders lie beyond the boundaries of its national parks. Beneath the waters within the National Marine Sanctuaries, a whole hidden world is submerged—a submarine realm where deep-sea spires tower, humpback whales glide and all manner of fishes reside. The country’s 14 marine sanctuaries, another of America’s best ideas, hold some of its most incredible marvels and reflect a stunning biodiversity. Created in 1975, the National Marine Sanctuary System protects more than 600,000 square miles of ocean and Great Lakes, spanning from the South Pacific to the North Atlantic.

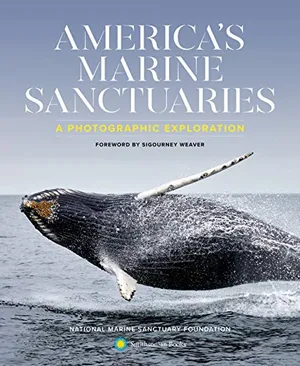

Now, readers can discover the awe-inducing mysteries of the oceans without leaving home. America’s Marine Sanctuaries: A Photographic Exploration, newly published by Smithsonian Books, takes readers on a comprehensive journey through the nation’s finest in underwater landscapes. Breathtaking images of wildlife and scenery are paired with profiles of each sanctuary location, along with accompanying commentary describing the sanctuary’s contributions to our society as well as tips for practicing stewardship to preserve the area for future generations.

The book details the magnificence of America’s marine sanctuaries, or as Walt Whitman once called it, “the world below the brine.” Each of the sanctuaries— American Samoa, Olympic Coast, Channel Islands, Cordell Bank, Florida Keys, Flower Garden Banks, Gray’s Reef, Greater Farallones, Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale, Mallows Bay-Potomac River, Monitor, Monterey Bay, Stellwagen Bank, and Thunder Bay—holds unique natural treasures. Below, Smithsonian magazine offers a sample of the aquatic havens featured.

America's Marine Sanctuaries: A Photographic Exploration

America's Marine Sanctuaries tells the story of fourteen underwater places so important they are under special protection, together forming the US National Marine Sanctuary System. These sanctuaries, spanning more than 620,000 square miles and ranging from the Florida Keys to the Great Lakes and to the Hawaiian Islands, are critical and breathtaking marine habitats that provide homes to endangered and threatened species.

National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa

Distinctive Features: Australia's Great Barrier Reef isn’t the only place that houses sprawling coral reefs: the American Samoa consists of five islands formed by volcanoes as well as two coral atolls that boast over 250 distinct coral species. One coral colony off the coast of the island Ta’u measures a whopping 22 feet in height. Scientists estimate that it is about 500 years old and consists of 200 million individual coral animals. Several of these massive Porite corals make up the aptly named “Valley of the Giants.” In addition to wildlife, the sanctuary helps preserve the culture and history of Samoans, a legacy dating as far back as 3,600 years ago when the Polynesian Lapita people first reached Samoa.

Fast Facts: The only sanctuary south of the equator houses 950 species of brightly colored fish and 1,400 types of marine invertebrates including giant clams, sea urchins and sea stars. Rose Atoll Marine National Monument, one of two national marine monuments, is situated within the sanctuary and is named for the pink patches of algae that distinguish the atoll’s reefs from the others. When it was designated in 1986, it was the smallest sanctuary at .25 miles. In 2012, however, it added large swaths of ocean and became the biggest sanctuary at 13,581 square miles.

Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale Marine Sanctuary

Distinctive Feature: Humpback whales, once populous in the world’s oceans, saw their numbers slashed by commercial whaling. A number of laws now protect the majestic animals, one of which created the sanctuary that is now the most important nursery for humpback whales in the Pacific. Here, the warmer Hawaiian waters suit the newly born calves, which lack the thick blubber that insulates their parents.

Fast Facts: Hawai’i also contains Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, a name that honors Papahānaumoku and Wākea, the earth mother and the sky god. A traditional story tells of their union, which created the Hawaiian Islands, the taro plant and the Hawaiian people. Because of how remote the area is, Papahānaumokuākea fosters reefs inhabited solely by species found nowhere else in the world, the only known marine area where all species are endemic. The largest marine conservation area in the world and a United Nations World Heritage site, the monument spans more than 580,000 square miles and is 1,350 miles northwest of the Hawaiian Islands. The Hawaiian Islands sanctuary, designated in 1992, is 1,366 square miles.

Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary

Distinctive Feature: The waters of this sanctuary are known for their abundant sea life, which thrives on the area’s seasonal upwelling, a phenomenon in which winds that blow across the ocean’s surface pushes the waters offshore, allowing colder, nutrient-rich waters to rise. These waters foster high biological productivity, attracting seabirds, whales, sea turtles that migrate thousands of miles to feed in the waters.

Fast Facts: The resources contained by the sanctuary, which spans 135 miles of coastline, are co-managed by four coastal native tribes, Hoh, Makah and Quileute, as well as the Quinault Indian Nation, in addition to the state of Washington and the United States. In 1855, treaties signed by Washington territory officials and the Coastal Tribes negotiated the ceding of thousands of acres of land in exchange for exclusive reservation lands and the promise of their right to hunt and gather resources at their usual areas. Olympic Coast, designated in 1994, is located on the coast of Washington State and is 3,188 square miles.

Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary

Distinctive Feature: The Monterey Canyon looms beneath the waters of Monterey Bay. More than a mile deep, its size rivals that of the Grand Canyon. The Davidson Seamount, in the southern area of the sanctuary, is among the largest known to humankind: it is 7,480 feet from top to bottom and still comes 4,000 feet short of the ocean’s surface. In 2018, researchers discovered an “octopus garden,” a nursery for the species, while exploring Davidson Seamount. The second found in the world, biologists estimated that conservatively 1,500 of the creatures live in the colony.

Fast Facts: The “Serengeti of the Sea” earns its nickname for its marvelous biodiversity, affording some of the most spectacular views for wildlife watchers in the world. More than 500 kinds of fishes, 180 species of seabirds and 36 marine mammal species grace the sanctuary’s waters. Monterey, designated in 1992, remains one of the largest national marine sanctuaries at 6,094 square miles.

Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

Distinctive Feature: Thunder Bay sits along northwestern Lake Huron, where cold, fresh water preserves a sunken treasure—a graveyard of ships. Taken down by collisions, storms and other forces of nature, more than 200 vessels rest in the dark depths of the lake. Thunder Bay is one of three national marine sanctuaries that commemorates America’s maritime history, along with Monitor and Mallows Bay-Potomac. The sunken ships represent vessels as varied as an 1844 wooden sidewheel steamer to a 20th-century German freighter. Together, the ships are like time capsules marking America’s transition from a sparsely populated wilderness to an industrialized superpower.

Fast Facts: The Great Lakes, the “Third Coast” of the United States, lay claim to the only freshwater national marine sanctuary and one-fifth of all of the fresh water on Earth: six quadrillion gallons. Four thousand three hundred miles off the coast of Michigan were designated as Thunder Bay in 2000.

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

Distinctive Features: From the 1500s through the 1700s, Spanish flotas, or fleets, carried pillaged silver and gold through the waters of the Florida Keys. Many Spanish vessels, as well as merchant and military ships, never arrived at their Key West destination after being done in by the hurricanes ripping in from the Caribbean. The strings of coral that populate the waters of the Keys are another obstacle for any schooner that tries to approach. The coral reefs of Tortugas Ecological Reserve, 70 miles past Key West, are the pride and joy of the sanctuary, and the reserve is the largest no-take marine reserve in the continental United States.

Fast Facts: Manatees, green sea turtles, herons and many-limbed mangroves are just a few of the Florida Keys’ most iconic species. The 3,800 square mile sanctuary protects over 6,000 species of marine life as well as 400 underwater historic sites, many of which are ships that sank in the notoriously perilous waters of the Florida Keys. The sanctuary was designated in 1990.

Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary

Distinctive Feature: Nearly a third of the sanctuary has been set aside as a designated research area, the greatest proportion dedicated to science out of all of the sanctuaries. Reserve managers get to control research activities so as to minimize the effects on marine life while allowing scientists to do their work. Gray’s Reef is unique from tropical reefs, which typically consist of hard coral, in that its foundation is formed of organic sediment consisting of shell fragments, sand and mud that were stuck together over millions of years. This formation process produced sandstone with numerous pores, allowing for plentiful growth of barnacles, snails, sea squirts and other invertebrates. The layer of these creatures that carpet the rocks they inhabit give the Gray’s Reef the appearance of a “live bottom.”

Fast Facts: The reef, designated in 1981, was discovered 20 years prior by biological collector and curator Milton “Sam” Gray. The small size of Gray’s Reef—22 square miles off the coast of Georgia—belies its significance to scientific discovery. The spot draws 200 species of fish including snappers, groupers and black sea bass, making it a popular fishing location.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4b/34/4b349dd7-95e6-449f-b981-c9cb587f27ed/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/74/3074ae5f-bd29-4119-9f23-a6db28ba3c85/longform_desktop.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tara.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/b0/6bb01836-347b-4c23-be1c-ed1483ddd2e0/page_58.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/4a/154aa08d-68a6-40c0-9f22-3d859f70b45e/page_59.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/be/76bed84d-9ca4-4159-a0c9-b4f899ecd820/page_10.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/90/ea908d8f-5d13-432f-a619-2552d05daab8/p9fixed.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/24/c024c733-ff32-4436-9c38-2654c5e3f1a9/page_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d6/00/d600481b-303c-4435-9a56-5f65113e6d86/page_70.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/28/8d28febf-32a3-4175-b8f0-ad608ff34077/page_84.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/d9/8ed9192b-9b04-4f0c-b594-000101f9f72b/page-85.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d3/f4/d3f43ca0-5e1c-4d8e-b854-7946bb278833/page_118.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/0a/f20a88fe-b559-4a8b-9def-413f9e72486e/page_119.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fb/53/fb531c27-55cf-4b9b-a746-1526cb5ca06e/page_120.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9b/3b/9b3bebc9-e007-4dfa-93a1-18ad329576d2/page_99.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/17/bd/17bdaeaa-3064-4cf1-b56d-6e94ebc30571/page_28.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d2/72/d2720207-ce2f-401e-8471-605f1b75bcb4/page_51.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tara.png)