Why the Chicano Underdog Aesthetic ‘Rasquachismo’ Is Finally Having Its Day

Next up for the podcast Sidedoor, actor and director Cheech Marin opines on the Chicano art sensibility that is defiant, tacky and wildly creative

:focal(1963x886:1964x887)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/d2/c9d23fcf-8dde-44c1-b498-526245121a3a/gettyimages-949064784.jpg)

“I have a T-shirt that says ‘Chicano art is American art,’” says Cheech Marin over a mid-morning breakfast in his hotel room.

During an interview last December before the Smithsonian’s Ingenuity Awards, Marin wore a T-shirt with the image of a skull embellished with bright colors and swirling designs—an image one might associate with the Mexican Dia de Los Muertos celebrations or the Pixar movie Coco.

Marin first made his mark on Hollywood with Tommy Chong in the 1970s in the pioneering Cheech and Chong films and albums, the irreverent marijuana-laced comedies that lit up America with such routines as “Earache My Eye,” “Basketball Jones” and “Sister Mary Elephant” and won Grammy recognition four years running from 1972 to 1975.

Marin’s days playing a stoner are far behind him, but the actor and comedian remains an innovative voice in American culture. Now, some of his most influential work is off-screen, as both collector and advocate for Chicano art, which he believes has long been overlooked by the fine art world.

In a new Smithsonian Sidedoor episode, Marin talked about his dedication to elevating Chicano art, especially the kind that reflects an inventive and survivalist attitude.

“When Chicano artists in L.A. wanted to show their art, they were told by the-powers-that-be at museums that Chicanos don’t make fine art. They make agitprop folk art,” he says, “agitational propaganda.”

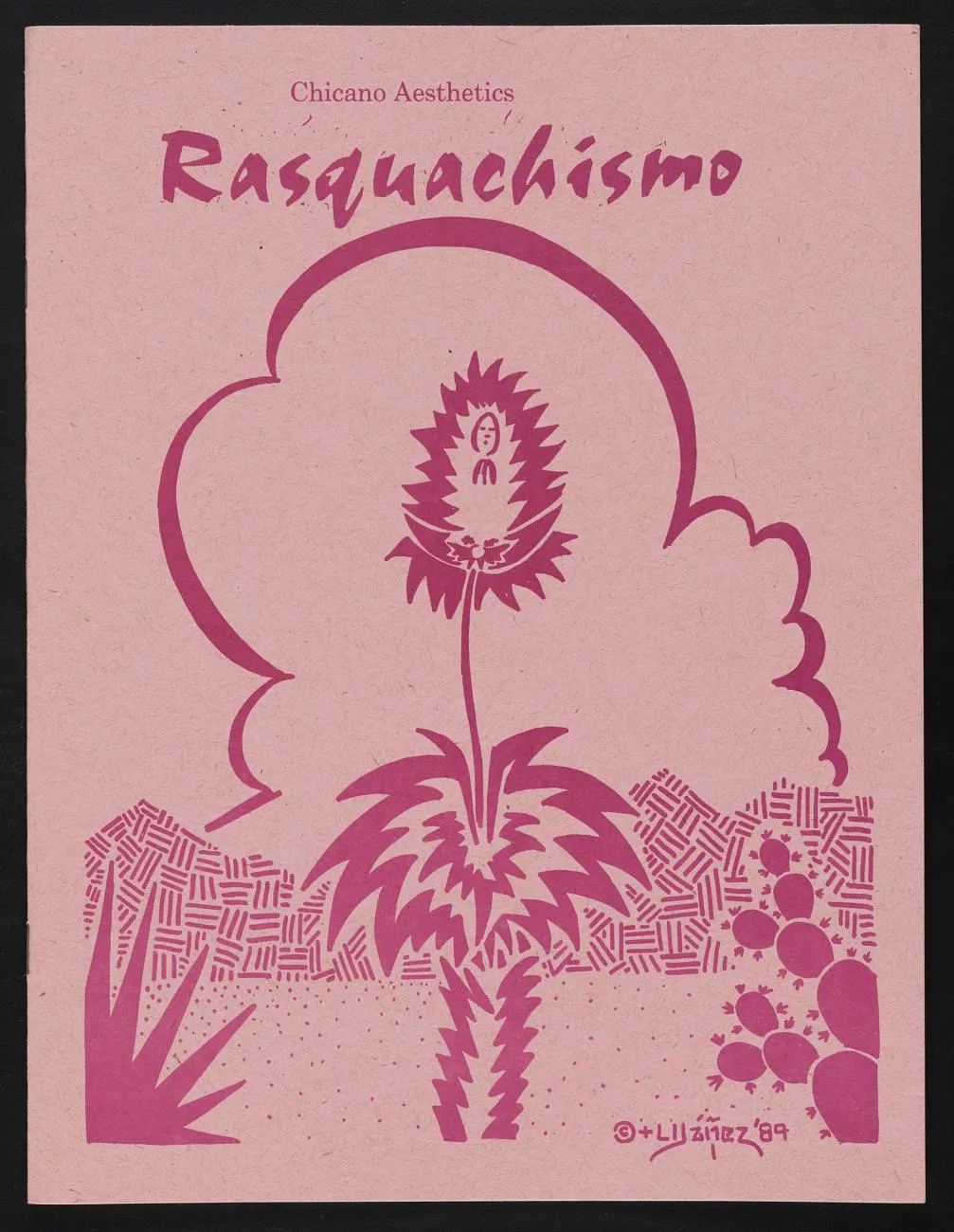

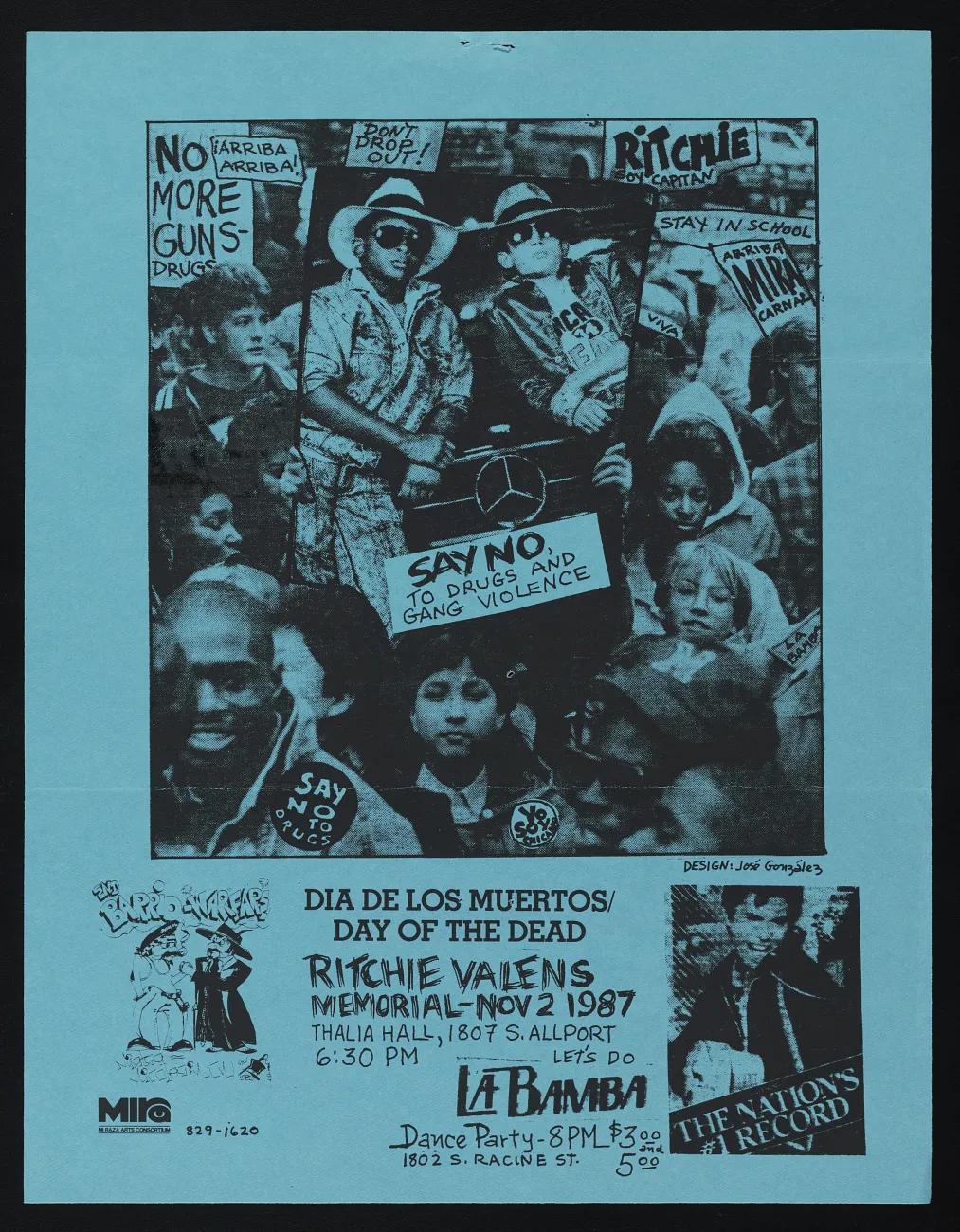

Much of the Chicano art of the 1960s and 70s, became linked with the posters and murals of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement calling for farmworker rights or resisting the Vietnam War. But in the forthcoming Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art, Culture, and Industry of the Riverside Art Museum, he will put his own private Chicano art collection, one of the largest in the country, on public display to showcase the range of this type of art. And some of the pieces will include one particular sensibility that’s growing in popularity—rasquachismo.

The term comes from the word rasquache, which has rolled off the tongues of Chicanos and Mexicans for generations to describe what is kitschy or crummy. Now, rasquachismo is entering the lexicon of artists, collectors and critics to describe an “underdog” aesthetic in Chicano art that is brilliantly tacky, gaudy and even defiant. It’s a sensibility that applies to everything from a velvet painting of cockfighting chickens to a self-portrait of an artist in a quinceañera dress against a backdrop of dollar bills.

“Anybody who knows rasquache recognizes it immediately. Rasquache is being able to take a little pushcart that sells ice cream cones and turn it into a three-bedroom house. That is the essence of it,” Marin says with a laugh. “You have to make art or something resembling art in your life with baser objects. It's not art made of gold, it’s made of tin, dirt or mud.”

As Marin launches his center in the predominantly Latino community of Riverside, California, collector Josh T. Franco is making sure that rasquachismo is also being documented in Washington, D.C. He’s been tapped by the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, which holds records of art in the U.S. that stretch back over 200 years, to document the movement. For him, the task is daunting.

He is amassing an archive of everything from photographs and publications to letters and tax returns that tell the story of Latino and Chicano art in America. His fascination with rasquachismo isn’t just a professional pursuit, though. It’s personal.

In the west Texas Chicano community Franco is from, the aesthetic was in the backyard—almost literally. He grew up close to his grandfather who made sculptures and a put-put course behind his home out of discarded playground items and found materials.

And in Marfa, Texas, in the backyard of the Sanchez family, who Franco also grew up with, stands a source of inspiration for his study of rasquachismo—an altar. It was built in 1997 from an upcycled bathtub, string lights and a plaster statue of the Virgin of Guadalupe to commemorate a modern-day miracle.

“Every night for two weeks there was a white shadow in the form of the Virgin of Guadalupe in the backyard against a tree,” Franco says. For the Sanchez family, the apparition was both miraculous and a natural product of the landscape.”

“I talked to Esther. . . the matriarch of the Sanchez family,” Franco says. “And she said ‘I know the shadow comes from the way that the light towers from the border patrol interact with the leaves from the tree, but why that shape (of Guadalupe)?’”

The appearance soon made the Sanchez family’s backyard a modern-day pilgrimage site, and Franco said people from Mexico, New Mexico and Texas came to visit. When the Virgin of Guadalupe could no longer be seen in their backyard, the Sanchez family honored the event by building the altar at the site.

While Church-related imagery is a frequent feature of rasquachismo, the lines of the aesthetic are blurry, if not nonexistent. An altar made of found objects is just as rasquache as a sleek and highly embellished lowrider.

“I think rasquachismo often is very messy and ad hoc, but I like to argue that lowriders are rasquache because it's shows a non-messy, methodical, polished, shiny expression of rasquachismo,” Franco says. “They're beautiful.”

The slow cruising cars have held a special place in Latino neighborhoods, west coast music videos, and Cheech Marin’s own movies for decades. Thanks to the work of Chicano artists and their advocates, lowriders and rasquachismo are being appreciated in the fine art world, but Franco still considers the recognition “a long overdue moment.”

“I feel responsible and scared,” he says, laughing. “I have to be responsible to my peers, but also my elders and people who, long before I had this job, I looked up to. Their legacies are important to me personally, but they are also just important to what the art history of this country will be in 100 years or 1,000 years.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Headshot_HaleemaShah.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Headshot_HaleemaShah.jpg)