Why a New Robin Hood Arises Every Generation

Troubled times always bring out the noble bandit who, in the face of tyranny and corruption, robs from the rich to give back to the people

:focal(905x246:906x247)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4c/62/4c62cb8c-8914-40a7-b6a1-b43a5558afe4/robin-hood-movies-gallery-07.jpg)

Folklore comes from the folk, which is why “robbing the rich to give to the poor” is a motif that has endured for centuries in the imagination of the people. When it comes to the redistribution of wealth in ballad and legend, heroes never rob from the poor to further enhance the fortunes of the rich.

The most recent illustration of this principle arrives in movie theaters on the day before Thanksgiving. Directed by Otto Bathurst, Robin Hood stars Taron Egerton in the title role, with Jamie Foxx as Little John, Ben Mendelsohn as the Sheriff of Nottingham and Eve Hewson as Marian.

The 2018 film version uses new digital technologies in many of the action sequences, but employs much of the same traditional folklore in casting Robin as the quintessential social bandit righting injustice by robbing from the rich and giving to the poor.

As the new blockbuster film settles into nationwide circulation, I went in search of the deep roots of the hero Robin Hood in archival records and folklore references. Assisted by Michael Sheridan, an intern serving at the Smithsonian’s Center for Folklore and Cultural Heritage, it soon become clear that in times of economic downturns, in times of tyranny and oppression, and in times of political upheaval, the hero Robin Hood makes his timely call.

We do not know if there ever was an actual Robin Hood in medieval England, or if the name simply attached itself to various outlaws in the 13th century. It is not until the late 14th century—in the narrative poem Piers Ploughman by William Langland—that references to rhymes about Robin Hood appear.

I kan noght parfitly my Paternoster as the preest it syngeth,

But I kan rymes of Robyn Hood and Randolf Erl of Chestre,

Ac neither of Oure Lord ne of Oure Lady the leest that evere was maked.

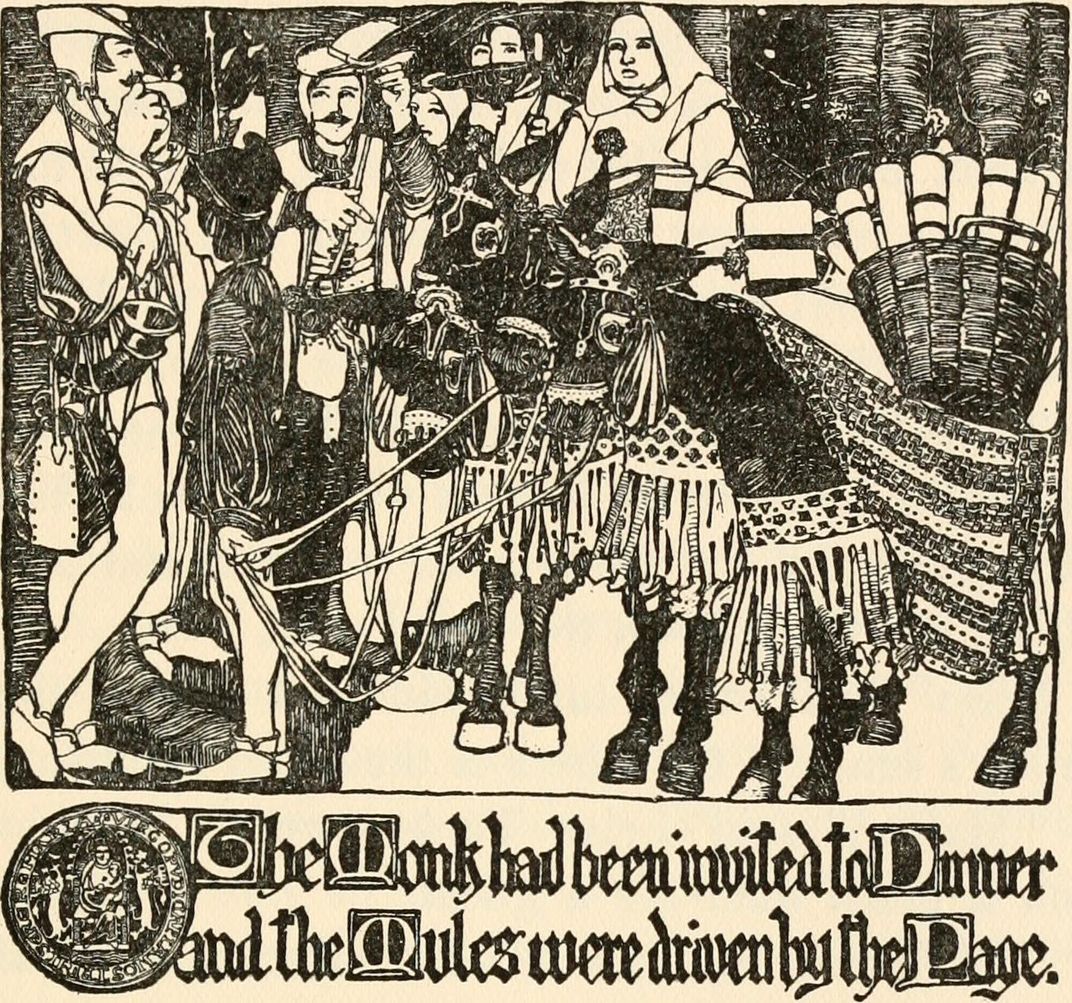

According to a timeline assembled by Stephen Winick at the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress, stories about Robin Hood continued to circulate for the next several centuries, gradually taking on many of the details that are familiar today: Robin as a “good” outlaw, according to Andrew of Wyntoun’s Orygynale Chronicle (ca. 1420); Robin living in Sherwood Forest, according to the ballad “Robin Hood and the Monk” (ca. 1450); Robin robbing the rich and giving to the poor, according to John Major’s History of Greater Britain (1521); and Robin as a noble earl, according to Richard Grafton’s Chronicle at Large (1569).

As these stories developed and spread, Robin became the quintessential “social bandit,” a term popularized in the late 20th century by the British historian Eric Hobsbawm. “Though a practice in social banditry,” he writes, “cannot clearly always be separated from other kinds of banditry, this does not affect the fundamental analysis of the social bandit as a special type of peasant protest and rebellion.” In other words, social bandits are not criminals, Hobsbawm maintains, but rather they are defenders of the honest folk against the evil forces of tyranny and corruption, especially during times of economic uncertainty. Moreover, Hobsbawm identified this as a worldwide phenomenon, including Balkan haiduks, Brazilian congaceiros, Indian dacoits, and Italian banditi.

Perhaps, what is most fascinating about Robin’s social banditry is how the folk tale has spread to certain outlaws in the United States, who (like the Robin Hood of the Middle Ages) are regarded as defenders of the folk. Take for instance, the tale A Gest of Robyn Hode, dating to around 1450, in which Robyn Hode aids a poor knight by loaning him 400 pounds so that the knight can pay an unscrupulous abbot. Robyn shortly thereafter recovers the money by robbing the abbot. Some 400 years later, a similar story is told about the American outlaw Jesse James (1847–1882) from Missouri, who is supposed to have given $800 (or $1,500 in some versions) to a poor widow, so that she can pay an unscrupulous banker trying to foreclose on her farm. Shortly thereafter Jesse robs the banker and recovers his money.

Jesse James rose to near celebrity stature in 1870s, active as a bank, train and stagecoach robber during a time of economic depression in the U.S., especially following the Panic of 1873. Twenty years later, the Panic of 1893 triggered another economic depression, out of which emerged Railroad Bill, an African-American Robin Hood whose specialty was robbing trains in southern Alabama.

The Great Depression of the 1930s saw a similar rise of other social bandits, who were often celebrated as Robin Hood hero figures. John Dillinger (1903–1934) from Indiana was seen as a crusader, fighting the enemies of the folk by robbing banks at a time when banks were known to collapse taking with them with their depositors’ savings and foreclosing mercilessly on home and farm mortgages. According to one oral history in the Folklore Archives at Indiana University, Dillinger became “a hero to the people, you know—kind of a Robin Hood. He would steal from the rich and give to the poor. . . . Everybody was poor then—we were in a depression, you see. Dillinger was poor. The only ones that were rich were the banks, and they were the ones who made everybody else poor.”

When Dillinger was killed by agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation outside a movie theater in Chicago, the title of Public Enemy Number One went next to Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd (1904–1934). Known as the “Oklahoma Robin Hood,” Floyd, according to Time magazine, was believed to be “always looking out for the little guy.”

“Rumors circulated that he had destroyed mortgage notes when he robbed banks, freeing struggling farmers from foreclosure.” One of Floyd’s fellow Oklahomans, Woody Guthrie, reaffirmed the Robin Hood legend with a ballad about Floyd helping the “starvin’ farmer” and “families on relief.”

Well, you say that I'm an outlaw,

You say that I'm a thief.

Here's a Christmas dinner

For the families on relief.

Contrasting the social bandit with white-collar criminals, Guthrie concluded, “some [men] will rob you with a six-gun, and some with a fountain pen.”

How and why Depression-era bandits like Dillinger and Floyd acquired their reputations as Robin Hoods must have been perplexing and frustrating for law enforcement officials. But many folklorists believe it’s partly a matter of circumstance—real-life bank robbers achieve renown during economic depression and partly also that the folk cannot resist creating new social bandits with traditional motifs in their own hard times.

The latter phenomenon may explain why social banditry is celebrated in nearly every film version made about Robin Hood, even when these films are produced by large Hollywood studios that may have more in common with the rich than with the poor.

Not much is known about the earliest such film, the 1908 Robin Hood and His Merry Men, but the first feature-length version, Robin Hood of 1922, following a sharp recession after World War I, was a spectacular success. Robin was played by Douglas Fairbanks, one of the most popular silent film stars, sometimes termed the “king of Hollywood,” who never walked on screen when he could leap and bound. His Robin good-naturedly relishes each new swordfight and opportunity to shoot arrows with great accuracy.

Errol Flynn, perhaps even more swashbuckling than Fairbanks with sword and longbow, played Robin next during the Great Depression in the 1938 The Adventures of Robin Hood, a Technicolor extravaganza that codified Robin as leader of a jolly band of bandits in Sherwood Forest, fighting passionately for truth and justice against unscrupulous noblemen who try to seize the English throne while King Richard the Lion-Heart is returning from the religious wars known as the Crusades.

These same elements have remained in nearly every film version since. Most notably for Sean Connery’s recession-era 1976 Robin and Marian, in which Robin returns to Sherwood Forest after the death of King Richard. Next, during the oil price shock economy for Kevin Costner’s 1991 Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, in which Robin fights against a conspiracy led by the Sheriff of Nottingham. And again, following the 2008 international banking crisis for Russell Crowe’s 2010 Robin Hood, in which Robin fights against a French conspiracy to invade England.

Theatergoers are no doubt in need of new Robin Hood folk hero in 2018. This year’s band of men and women in Sherwood Forest remain merry even as the evil forces of tyranny and corruption seek to marginalize them in 21st-century fashion.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)