Why Religious Freedom and Diversity Flourished in Early America

Jam-packed exhibition features artifacts as diverse as Jefferson’s Bible, a steeple bell cast by Paul Revere and a storied Torah

In theory, Reverend John Eliot’s 1663 scripture was the perfect proselytizing tool. Entitled Holy Bible Containing the Old Testament and the New; Translated into the Indian Language, the text was adapted for an indigenous audience and, ostensibly, had an advantage over opaque English sermons.

Eliot learned Algonquian in order to translate the Bible, but unfortunately for both parties, the oral language had no written form. The reverend had to transcribe his oral translation—and teach his audience how to read the text. The Algonquian Bible is a touchstone of American religious history: It was the first Bible published in English North America, predating by 80 years its earliest successor, a German text used mainly in Pennsylvania churches.

“Religion in Early America,” a new exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, displays Eliot’s holy book alongside artifacts including Thomas Jefferson’s personalized Bible, a 17th-century iron cross made by the first Catholic community in North America and a 19th-century manuscript written by an enslaved Muslim. The exhibition marks the museum’s first exploration of spirituality during America’s formative years and traces religious diversity, freedom and growth between the colonial period and the 1840s.

One of the show’s recurring themes is the evolution of European-born religions in a New World setting. A 1640 edition of the Bay Psalm Book, a Puritan hymnal, was one of the first texts published in North America. In a clear embrace of their new religious context, the colonists chose to translate the hymnal from its original Hebrew text instead of reprinting an English edition. Joseph Smith’s Book of Mormon, published in 1830, incorporates indigenous Native American groups into the European Biblical narrative.

The religious landscape of early America encompassed more than competing Christian denominations, and these smaller communities are also represented. Groups including enslaved Muslims, Jewish refugees, and adherents of Gai-wiio, a blend of Quaker and Iroquois beliefs, existed at the margins of the dominant Christian population. The presence of such groups was once common knowledge, but as faiths evolved, elements of their history were forgotten.

For Peter Manseau, the museum’s new curator of religious history, the exhibition is an inaugural event in a five-year program designed to integrate faith into the collections through scholarship, exhibitions, events and performances.

“You can’t tell the story of American history without engaging with religion in some way,” Manseau explains.

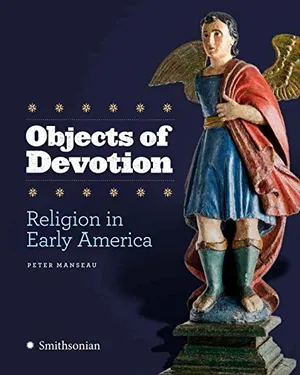

Objects of Devotion: Religion in Early America

Objects of Devotion: Religion in Early America tells the story of religion in the United States through the material culture of diverse spiritual pursuits in the nation's colonial period and the early republic. The beautiful, full-color companion volume to a Smithsonian National Museum of American History exhibition, the book explores the wide range of religious traditions vying for adherents, acceptance, and a prominent place in the public square from the 1630s to the 1840s.

Eliot’s Algonquian Bible, for example, reveals a key motivation for colonization: the spread of Christianity. Hoping to extend his translated text’s reach, the reverend created an accompanying guide to the written word and offered to visit “wigwams, and teach them, their wives and children, which they seemed very glad of.” Although the Algonquian Bible was a difficult read for its intended audience, the text grew popular across the Atlantic—in an ironic twist, English Christians saw the Bible as a symbol of colonists’ evangelical success.

Soon after the first settlers’ arrival, new communities and dissenting religious beliefs began to spread across the continent. Early religious activist Anne Hutchinson championed the right to question Puritan tenets in 1636, while fellow reformer Roger Williams founded the settlement of Rhode Island, known for its religious tolerance and separation of church and state, that same year. Pacifist Quakers, ecstatic Shakers and fiery evangelicals built their own communities in places like Pennsylvania, New York and New England. Adherents of religions outside of the Christian tradition—including the Jewish families that arrived in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1658—did the same.

This outpouring of faith established a connection between religious diversity, freedom and growth. “If they didn’t find a way to live together, they would never create a society that would function as one,” Manseau says. “And, contrary to the fears of many in early America, this creation of religious freedom did not lead to the decline of religion as a cultural or moral force, but rather led to explosive growth of religious denominations.”

The items chosen to represent diverse faiths in America run the gamut from George Washington’s christening robe and a 17th-century Torah scroll to unexpected objects such as a compass owned by Roger Williams. The religious reformer, who was exiled from Massachusetts due to his “great contempt of authority,” used the compass on his journey to Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island. There, he created a new colony built on the premise of religious liberty for all.

“He literally finds his way there with this compass,” Manseau says. “It’s not an obviously religious object, but it becomes part of this significant story of religion in early America.”

One of the Smithsonian’s newest acquisitions—an 800-pound bronze bell commissioned in 1802 for a Maine Congregational church—reveals the chapter of Paul Revere’s life following his famous midnight ride. The Revolutionary War hero was a talented metalsmith, and in 1792, he expanded his business with the family-run foundry Revere and Son.

The first bells produced by Revere’s foundry were met with mixed reviews. Reverend William Bentley of the Second Congregational Church in Salem, Massachusetts, commented, “Mr. Revere has not yet learned to give sweetness and clearness to the tone of his bells. He has no ear and perhaps knows nothing of the laws of sound.” Despite this critique, the reverend purchased a Revere and Son bell, maintaining that he had done so out of patriotism.

The metalsmith turned bell maker soon honed his craft and moved on to cannons and rolled copper. He continued working with the foundry, however, and by his death in 1818, had cast more than 100 bells. The foundry remained operational after its patriarch’s death but shut down in 1828 after producing a total of 398 bells.

The Bilali Document is a reminder of a history all but forgotten. Written by a man named Bilali Muhammad, the 13-page document is the only known Islamic text written by an enslaved Muslim in America. Historians estimate that about 20 percent of the men and women seized from Africa were Muslim, and the Bilali Document represents their struggle to keep Islamic traditions alive.

Omar ibn Said, a Senegalese man taken from his homeland in 1807, converted to Christianity after several years of slavery. His autobiography, The Life of Omar ibn Said, Written by Himself, reveals that Said blended elements of Christianity and Islam and hints that he converted out of situational necessity rather than spiritual conviction. Said’s tale sheds light on the plight of Bilali Muhammad and other Muslim slaves, whose stories have been lost over centuries of coercion, captivity and conversion.

“The place of religion in America has always been complex, and it’s always been a matter of negotiation,” says Manseau. “This simple fact of religious freedom has never guaranteed that there wouldn’t be tensions between religious traditions.”

“Religion in Early America” is on view at the National Museum of American History until June 3, 2018.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6e/ac/6eacc63d-cf17-4992-b377-f90cb9e61824/img_9579.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4b/41/4b41d087-06e6-4875-a531-a8d184ec5066/lucretia_motts_bonnet_1_rws2016-09090.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/48/30489804-877f-42c9-b30a-dd283eac2fa6/treated_open_title_page_blacket2011-09342.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)