Why the Smithsonian Folklife Festival is Anchoring a 30-Foot Kenyan Sailing Vessel on the Mall

The 10-day-long celebration of global culture, featuring Kenya and China, takes place in late June and early July

Nestled in the Indian Ocean just off the northern coast of Kenya, the isolated archipalegeo of Lamu allows visitors to sail hundreds of years back into time.

Lamu was the most conspicuous melting pot in East Africa in the 1800s, a place whose wealth reflected Swahili, Arab, Persian Indian and European influences. For centuries, its fortune largely rested on the dhow, a hand-hewn, wooden boat that skimmed the islands’ shores. Monsoon winds carried the vessels, laden with gems, silks and spices, to harbors as far away as China and the Arabian Peninsula. As a result, the far-flung Lamu became both an important port and a hotbed of cultural fusion.

Once a notable Swahili stronghold, Lamu Town—the archipelago's largest urban center, located on Lamu Island—now draws visitors as a Unesco World Heritage site. This year, the 48th annual Smithsonian Foklife Festival will spotlight Kenya as part of a two-country program that also features China. In honor of the occasion, the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage will transport one of its ancient wooden watercrafts (aptly named “Lamu”) all the way from East Africa to the National Mall in Washington, D.C. There, says Preston Scott, a Festival curator, it will stand as a tribute to Kenya’s diverse heritage.

“One of the themes we're celebrating this year [at the Foklife Festival] is Kenya as a cultural melting pot throughout history, particularly along the coast,” says Scott. “The dhow was really the instrument that allowed all of that to happen—exchanges with trade, language, food, dress, religion, everything.”

Lamu boasts the historical honor of being Kenya's oldest continually inhabited town. Founded in 1370, it was one of the original Swahili settlements along coastal East Africa, and attracted an influx of notable Islamic scholars and teachers; today, its coral stone homes and narrow streets remain sparsely populated by locals, tourists and donkeys (an estimated 2,200 of the animals live on Lamu island, and are used for agriculture and transport). Despite a looming—and controversial—construction project that seeks to spend billions building a megaport and oil refinery in the region, the island has remained largely untouched. There are no cars on the island; locals must walk or rely on dhows for coastal travel.

“It’s a remarkable place,” says Scott, who’s traveled to Lamu several times in preparation for the Folklife Festival. “It’s kind of stuck in time.”

If Lamu’s stuck in time, then the dhow’s exact origins are lost in time. The boats are thought to have Arab roots, but many scholars trace their inception all the way back to China. The teak hulls are long and thin, and the sails are large and usually hand-stitched. There are no cranks or wenches for the canvas; sailors must pull on ropes to navigate the vessel through the water. Since the dhow can cut swiftly and cleanly through vast swathes of ocean, Lamu often hosts large-scale races that pit Kenya’s most seasoned sailors against each other in a competition that’s equal parts living history and sea-savvy.

Despite the dhow’s storied past, its fleet-sailed future is on the wane. Very few cultures in the world continue to use dhows for everyday use, and their construction is faltering in other Eastern nations, like Oman, that once also considered the dhow a vital cornerstone of life.

“But dhow building’s still vital in Lamu,” says Scott. “The fishermen go out every single day. Dhows aren’t just decorative items or museum pieces.”

During Scott’s travels to East Africa, he saw dhows speed through the region’s waterways and thought “‘Wow, wouldn’t it be great to bring one to Washington,’ not realizing we might even be able to do it.”

Scott’s sights eventually settled on a 30-foot-long dhow, fashioned 10 years ago by a famous boat builder. “It’s teak; it's all made of wood,” says Scott. “It’s all handcarved, with handmade nails. It’s very elegant.”

The dhow’s maker had died. But his son, Ali Abdalla Skanda, offered to restore the boat for Scott...and for the Folklife Festival.

This past month, the dhow was hauled off a beach and loaded into a truck bound for Mombassa, Kenya’s second-largest city located eight hours north of Lamu. A freighter is shipping it all the way to Baltimore, where it will then be floated inland—and trucked once more—to Washington, D.C. By the end of June, says Scott, the dhow will hopefully be safely ensconced by grass and trees on the National Mall.

“Skanda will have a shipbuilding tent nearby with all his tools,” says Scott. “He’s actually bringing one assistant with him, too—a dhow builder from Lamu named Aly Baba. The dhow will be up and on a platform, and they will be finishing some of its carving and painting.”

After the Festival, where will the dhow go next? Scott says he hopes that the boat will become part of the Smithsonian's collections at the Museum of Natural History.

“It’s a symbol of cultural crossroads,” he says.

Inaugurated in 1967 by the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the Folklife Festival is held each July in Washington, D.C., and aims to promote the understanding and continuity of grassroots cultures around the world. This year, the 10-day event is split into two programs. One side of the National Mall will focus on Kenya’s role as a cultural and coastal meeting point throughout history, highlighting the ways its people protect its land and heritage. The other, meanwhile, will celebrate China’s vast diversity with a host of participants who come from 15 regions and represent some of the country’s 56 ethnicities.

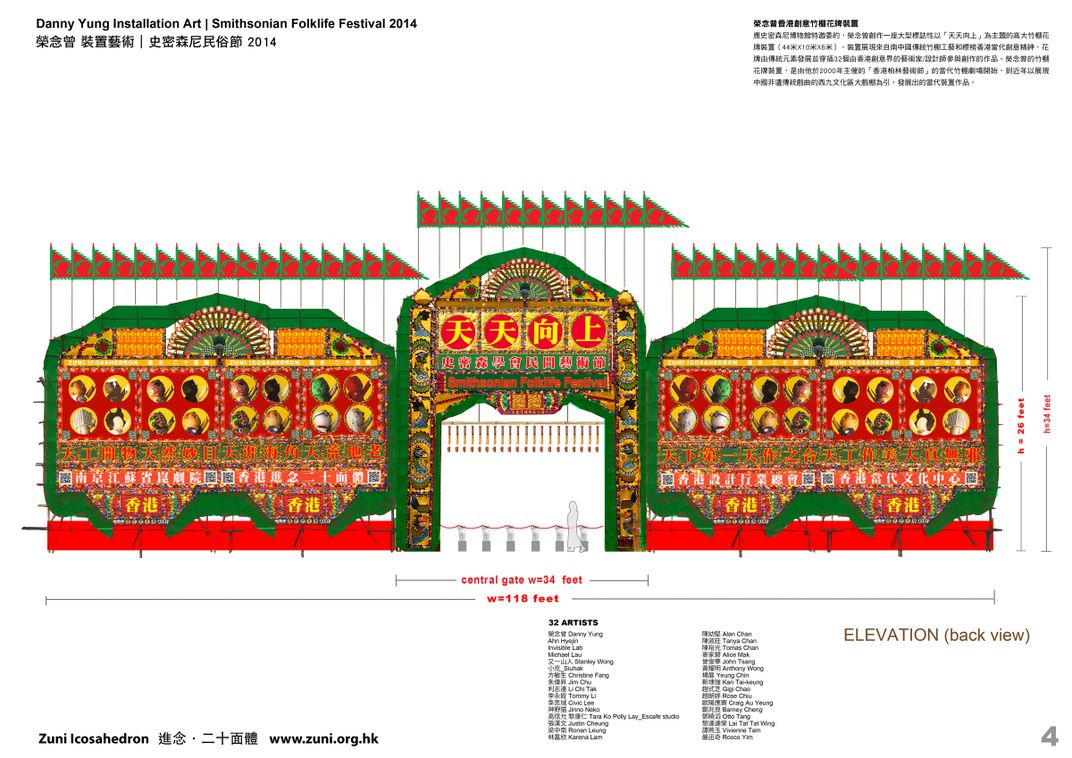

The China Festival offerings include a People’s Park—a public Chinese gathering area in which individuals will join together for collective exercising, singing, dancing and games. Attendees can also get crafty in China’s “Family Style” tent, which will offer children and parents alike the chance to learn dances, make paper lanterns and kites, press a design into a moon cake and learn Mandarin phrases. Additionally, a festive Chinese flower plaque will be assembled from 40-foot containers of imported bamboo and erected on the Mall; it will be accompanied by other vivid cultural symbols, including a moving dragon-lion cart that will serve as a prop to a Chinese Wu opera troop.

James Deutsch, curator for the China program, says that one fascinating aspect of working on the program was the knowledge that so much of our historical culture is rooted in ancient Chinese culture. “We’ve been writing texts for visitors to get acquainted with the customs we’re featuring, and we had to resist the temptation to say, ‘You know, this goes back more than 2,000 years.’ But the fact is, it’s true.”

“Calligraphy and paper go back to China,” continues Deutsch. “Many of our musical instruments go back to China. Porcelain—which we call china—is given that name because, well, that’s where it comes from. So that’s just one fascinating aspect of working on this program, thinking about these really long traditions of continuity and change.”

The Folklife Festival runs from June 25, through Sunday, June 29, and Wednesday, July 2, through Sunday, July 6. The Festival is held outdoors on the National Mall in Washington, DC, between the Smithsonian museums. Admission is free. Festival Hours are from 11 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. each day, with special evening events beginning at 6 p.m. The Festival is co-sponsored by the National Park Service.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Fawcett-Bio.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/2b/d12bca45-6732-48fa-a798-7aaf65409836/dhow3.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Fawcett-Bio.jpg)