Why the Smithsonian Just Can’t Quit Studying the Civil War

150 years later, the war is still in focus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/SEP13_H01_Secretary_631x300.jpg)

It’s only one weapon among the 5,700 in the firearms collection of the American History Museum, but it speaks to the Civil War in a very personal way. Under the watchful eye of curator David Miller, I hoist the 1863 Springfield rifle musket to my shoulder and feel its weight, with deepening respect for those who used these muskets with deadly results. This particular weapon was owned by Pvt. Elisha Stockwell Jr., who lied about his age to sign up, at age 15, with the Union Army. He took canister shot in his arm (and a bullet in his shoulder) at Shiloh, marched with General Sherman toward Atlanta, and, at 81 and nearly blind, finally put pen to paper to write about his experience.

“I thought my arm was gone,” he wrote of the moment the grapeshot struck him, “but I rolled on my right side and...couldn’t see anything wrong with it.” Spotting ripped flesh, a lieutenant had Stockwell sit out a charge against the “Rebs,” possibly saving his life.

The musket young Elisha used also speaks volumes about the technology of the day. In a Smithsonian symposium last fall, Merritt Roe Smith of MIT argued that the creation of the technical know-how that could produce precisely tooled, interchangeable parts for hundreds of thousands of rifles, a feat the South couldn’t match, set the stage for explosive industrial growth after the war.

The Smithsonian’s observation of the Civil War’s sesquicentennial encompasses exhibitions at many of our 19 museums. For an overview of exhibitions and events and a curated collection of articles and multimedia presentations, check out Smithsonian.com/civilwar. Be sure to experiment with the interactive map of the Battle of Gettysburg, which, in addition to troop movements, displays photographic panoramas of the terrain as various military units would have seen it.

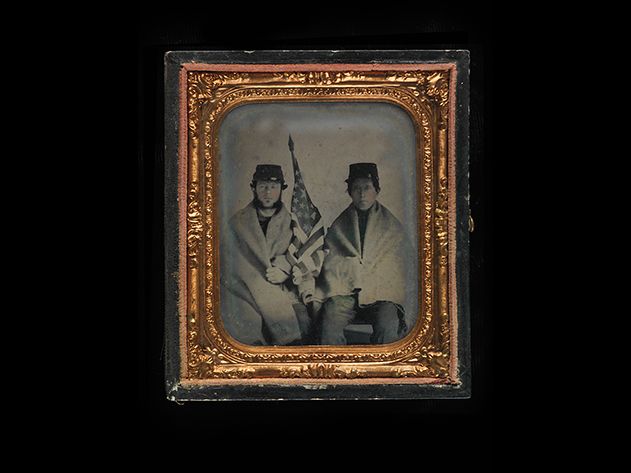

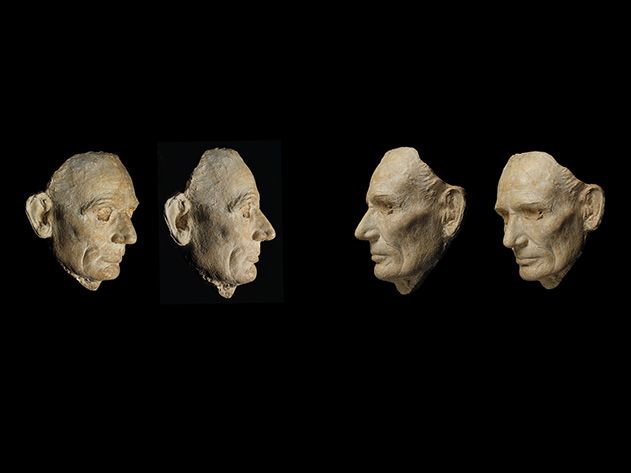

One high point of our Civil War remembrance is the richly illustrated Smithsonian Civil War: Inside the National Collection, to be published next month by Smithsonian Books. Our curators and historians selected 150 noteworthy and often moving objects to write about: weapons, uniforms and portraits, but also a slave-ship manifest, plaster casts of Abraham Lincoln’s face and hands, and photographs of hydrogen-air balloons used by the Union for surveillance. Three shows tied to the book will air on the Smithsonian Channel.

Also next month, Smithsonian Books will publish Lines in Long Array, which includes historical poetry about the war alongside contemporary verse. Sectional hatred nearly rent asunder the young United States, but Herman Melville captured the way the war’s unimaginable carnage could erase distinctions between Blue and Gray in a poem called “Shiloh: A Requiem (April, 1862),” set in the battle’s aftermath: “natural prayer / Of dying foemen mingled there— / Foemen at morn, but friends at eve— / Fame or country least their care / (What like a bullet can undeceive!).”