One of my last pre-pandemic memories of working at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, where I am a biological anthropologist, was an early morning chat with a global health colleague. It was late February 2020, before the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed that Covid-19 was possibly spreading person-to-person in communities across the United States. We were in the museum’s lobby watching the crowds arrive that morning, a steady stream of visitors, many on their way to see our exhibition on emerging infectious diseases and One Health.

While we talked about her recent television interview on the latest information about the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, her face tensed. She told me, with unforgettable urgency: “We need to change the narrative. This is a pandemic.” It’s too late to keep the virus out, she meant, counter to a lot of messaging at the time. We could only slow it down.

As the curator of the exhibition “Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World,” I had been collaborating with a lot of experts to educate the public about how and why new zoonotic viruses emerge and spread, and ways that people work together across disciplines and countries to lower pandemic risks. We opened the show in May 2018, not anticipating that a pandemic—publicly declared by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020—would shutter it less than two years later.

On this grim anniversary, in a world reckoning with more than 2.5 million virus-related deaths and functionally distinct variants of the virus circulating, the museum remains closed. And while working still at home, I sit with the certainty that we need to once again change the narrative. Not just about Covid-19, but pandemics in general. Even after the latest coronavirus is brought under control, humanity will continue to face new pandemics because we cause them, by ways that we are and things that we do. If we understand why, then we can better control how.

Pandemic risks are hardwired in human beings. From the evolutionary history and biology of our species, to the social and cultural conditions of our behavior, to the cognitive and psychological processes of our thinking, we can see our challenges by looking a bit closer at ourselves.

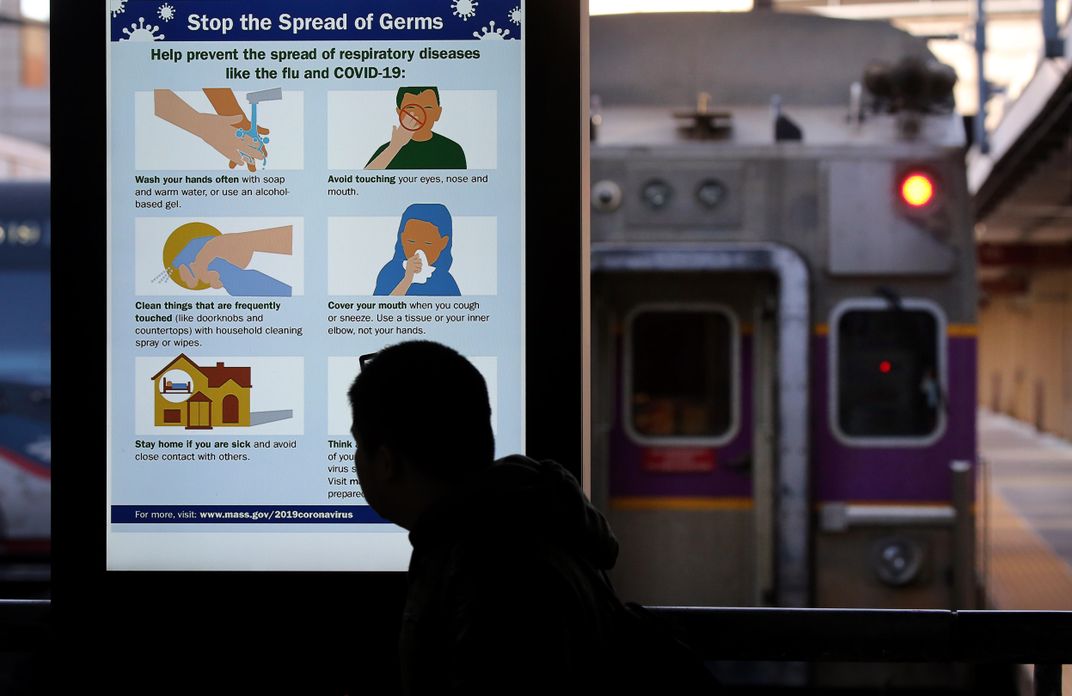

Much of the pandemic potential of SARS-CoV-2 lies in how easily and unwittingly people can infect each other. The emission of infectious respiratory particles—that is, virus-containing aerosols and droplets that are generated when an infected person breathes, talks, laughs, sings, sneezes and coughs—is a major source of transmission. To reduce the airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2, mask wearing is effective, with layered interventions that also include hand hygiene, distancing, ventilation and filtration. All of these measures serve to counteract some of the latent liabilities of our pandemic-prone species.

Another pandemic feature of SARS-CoV-2 is its newness to humans, who have only just encountered this virus, with limited defenses and a number of evolutionary disadvantages against it. As a Pleistocene latecomer to the natural world, Homo sapiens are accidental hosts of many zoonotic pathogens like SARS-CoV-2. We create opportunities for these pathogens to infect and adapt to us when we disturb their natural hosts and ecosystems, or enable their transmission among other nonhuman animals, such as those that we protect, farm and consume.

Human activities including deforestation, industrialized food production and wildlife trade have been driving the emergence of new zoonotic pathogens with increasing frequency since the 20th century. Genetic analyses indicate that SARS-CoV-2, like 75 percent of emerging zoonotic pathogens, originated in wildlife. Close similarities to viral genome sequences from bats and pangolins in East Asia have helped narrow down its potential reservoirs of origin, although we may inadvertently create new reservoirs for its reemergence.

Our unique biological traits also contribute to the pandemic spread of pathogens, once a spillover from another species occurs. Human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 wouldn’t be nearly so successful without our widespread use of oral language, made possible by the human brain and throat. Our vocal tract, with its singular configuration of tubes, evolved to expel an alphabetic array of speech sounds at an astonishing rate. As such, it is also well tuned to broadcast viruses like SARS-CoV-2 that replicate in the upper respiratory tissues.

Nor would the transmission of pathogens be so easy without the functionality of the human hand. Our dexterous thumb and fingers, with their unique proportions and opposability, place the world at our pulpy fingertips—along with millions of microbes collected by our noteworthy nails and fleshy apical pads. These defining features of human anatomy are extraordinary benefits for consumption and innovation that helped H. sapiens overtake the planet. Yet, ironically, they facilitate existential disease threats to us today.

Modern civilization has also primed us for the propagation of new infectious diseases, as most humans now live in constant contact within large, dense and globalized populations. This lifestyle is a recent ecological path from which we can’t turn back. Our anatomically modern ancestors thrived as small, dispersed and mobile groups of foragers for more than 300,000 year history, but our shifts to sedentism and agriculture over the last 12,000 years has now shaped our foreseeable future.

With population growth helped by domesticating and accumulating food, our predecessors started to build their environments and create long-distance links between them. Aggregating in urban centers with expanding spheres of influence, they constructed granaries, raised livestock and established trade networks by which pandemic pathogens eventually began to spread across ancient empires—via nonhuman hosts and vectors, aided by human transportation. Many of these pathogens are still with us, while others like SARS-CoV-2 continue to emerge, as pools of potential hosts increase and international travel connects us all.

Human social habits and cultural customs, too, affect the transmission of pathogens. Like other primates, H. sapiens form stable social groups that depend on bonded relationships for cohesion and support. In the same way that nonhuman primates foster these social bonds through grooming, people elicit feelings of closeness through physical touch and direct interaction—as when we hug and kiss, gather and dance, and eat and drink communally.

The cultural significance of these behaviors can deepen our reliance on them and heighten the infectious disease risks that they pose. Indoor dining, air travel and religious congregation are just a few of the ways that we maintain these social relationships and by which SARS-CoV-2 has spread.

Yet the strength of social rules that constrain our behaviors is another factor in the spread of disease. In some countries where weaker and more permissive social norms are less conducive to cooperative behaviors, cultural looseness may partly explain the country’s higher rates of Covid-19 cases and deaths, compared to stricter countries in which mitigation measures have been more successful in limiting them. The level of political polarization in a country, as well a the nature of its government's communications about the virus, should also be considered. Both led to the divisive politicization and resistance of public health measures in the U.S., which has accounted for at least 20 percent of Covid-19 cases globally since March 2020.

People also differentiate social groups by who is not a member—sometimes by processes and constructs of othering that are evident across societies as well as during pandemics. Scapegoating, stigmatization and xenophobia are among the first responders to a new illness, whereby groups who are viewed as opposite, inferior and not us are blamed for disease transmission. This is a prominent pattern in origin stories and conspiracy theories of diseases, which often pathologize exotic places and allege foreign malfeasance to make a new threat seem more comprehensible and controllable.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, some U.S. leaders have deflected responsibility for Covid-19’s devastation with “Kung Flu” and “China Virus” slurs, stoking anti-Asian racism and deadly hate crimes. Othering is also intertwined with systemic racism and structural violence against historically marginalized groups in the U.S., resulting in glaring health disparities that Covid-19 has further emphasized.

And because we are human, we have a tendency to ascribe human characteristics to the nonhuman domain. We perceive faces in clouds, anger in storms and tremendous powers in pathogens. Called anthropomorphism, this is a common phenomenon that makes the unknown seem more familiar and predictable. Often people anthropomorphize with good intentions, to explain a concept, process or event—such as a novel virus—that is not easily understood.

Yet this framing is misleading, and in some ways unhelpful, in communicating about pandemics. Over the past year, the coronavirus has been described like a supervillain as “lurking” among us, undetected; “seeking” new victims; “preying” upon the most vulnerable; “outsmarting” our best defenses, and ultimately as “Public Enemy Number One.”

Far from a criminal mastermind, SARS-CoV-2 is merely a piece of genetic code wrapped in protein. It is unable to think or want. It does not strategize or make decisions. And it cannot do anything on its own—not even move. So why do we say that viruses like SARS-CoV-2 can “jump” between animals or “hitch a ride” to a host, as if they had propulsive legs and prehensile hands? This manner of speaking misdirects our attention from our true challenger: us.

Here’s the narrative that nobody wants, but everyone needs: There will be another pandemic. When it happens and how bad it becomes are largely within our highly capable human grasp—and will be determined by what we do with our extraordinary human brains.

Remarkable scientific advances in vaccine development over the past year may expedite an end to the current pandemic of Covid-19, but they cannot eradicate a zoonotic pathogen like SARS-CoV-2.

We also must direct our unmatched brainpower towards economic, technological and ecological changes that recognize the interconnectedness of human, animal and environmental health, so that we can prevent the emergence of new pathogens as much we can, and be prepared for them when we don’t.

It is a hallmark of our cognitive abilities to calculate and respond to future probabilities. We will have to adapt to this pandemic reality, but adaptation is something that humans are famously good at. It’s what got us here.

When the “Outbreak” exhibition finally reopens, it will have adapted, too. The content will be updated, the interactive experiences may be more limited, and every single visitor will be a pandemic survivor. But its messages of One Health and global cooperation will be the same, just as important now as they were a year ago. Although the show is in a museum, it’s not about the past. It’s about what’s now and what may be next.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/36/b43625a0-e57e-4f9e-ba41-65de24a87919/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/a1/b0a1f723-8ba2-4aba-ab18-5c56dd4b5b67/afasdf.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sholts_head_shot.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sholts_head_shot.jpg)