Why Thomas Jefferson Created His Own Bible

In a new book, Smithsonian curator of religion Peter Manseau tells of how The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth first sparked hot controversy

:focal(1640x701:1641x702)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/e8/50e85c8c-bf13-46d1-bf90-2eea374ae0bb/gettyimages-1153804240.jpg)

Great religious books are often inseparable from tales of their discovery. Whether it is Joseph Smith unearthing the golden plates that would become the Book of Mormon, or Bedouin shepherds stumbling upon the cave-hidden jars that yielded the Dead Sea Scrolls, part of the significance of some sacred texts is derived from stories presenting the possibility that they might have never been known at all.

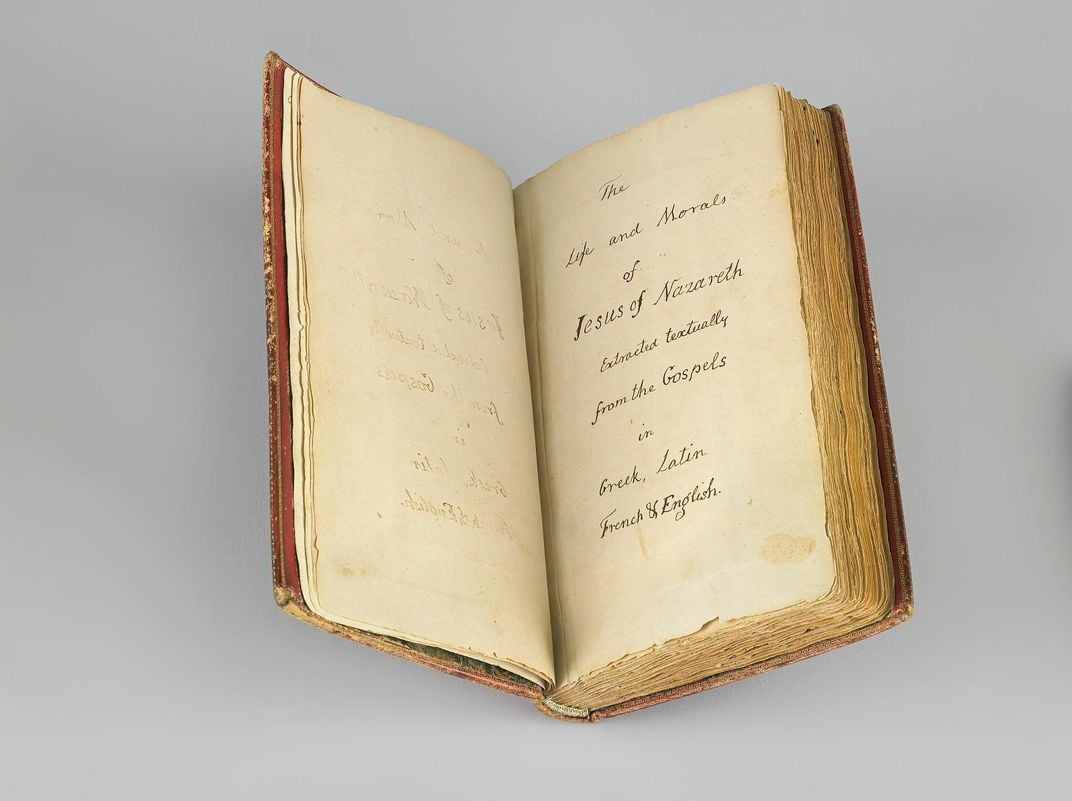

The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth—popularly known as the Jefferson Bible—is another such book. Completed by Thomas Jefferson 200 years ago this summer, the infamous cut-and-paste Bible remained all but forgotten for the better part of a century before an act of Congress brought about its publication in 1904. Since then, it has been as controversial as it has been misunderstood.

The 86-page book, now held in the collections of the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, is bound in red Morocco leather and ornamented with gilt tooling. It was crafted in the fall and winter months of 1819 and 1820 when the 77-year-old Jefferson used a razor to cut passages from six copies of the New Testament—two in Greek and Latin, two in French and two in English—and rearranged and pasted together the selected verses, shorn of any sign of the miraculous or supernatural in order to leave just the life and teachings of Jesus behind. Jefferson, who had suffered great criticism for his religious beliefs, once said that the care he had taken to reduce the Gospels to their core message should prove that he was in fact, a “real Christian, that is to say, a disciple of the doctrines of Jesus.”

While certain members of the Jefferson family were aware that this highly redacted compendium of scripture had served as their esteemed forbearer’s nightly reading at Monticello, we would likely not know more about it if not for the work of a pair of men who happened to have the skills, interests and connections necessary to appreciate and make something of what they had found.

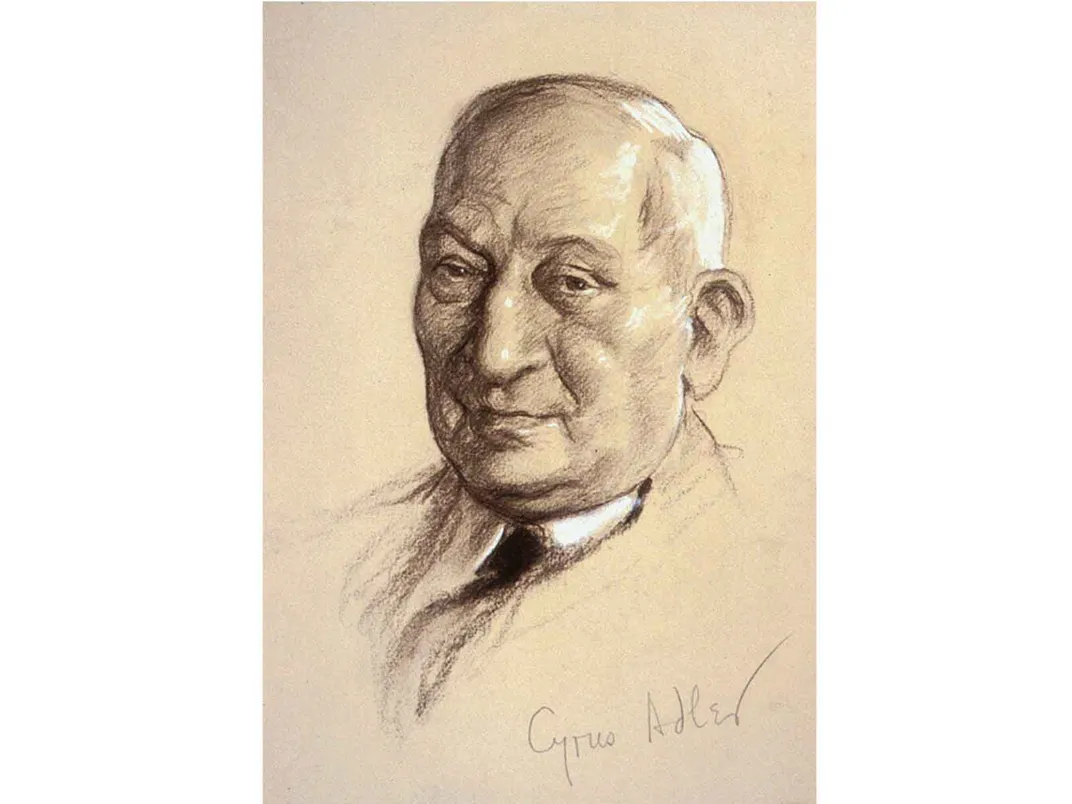

The first, Cyrus Adler, was the son of a Arkansas Jewish shopkeeper who, in a quintessentially American story of reinvention, ended up first a professor of Semitic languages at Johns Hopkins University and later one of the most influential public historians of his generation. He helped found the American Jewish Historical Society, and eventually became an advisor on religious issues to U.S. presidents.

Before reaching such heights of influence, Adler served from 1888 to 1908 as a curator, librarian and director of the division of religion at the Smithsonian Institution, which tasked him with seeking out and collecting unique examples of the material culture of American religion.

Several years before, while still completing his doctoral studies, he had been hired to catalogue a private library. “In 1886 I was engaged, when a fellow at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in cataloguing a small but very valuable Hebrew library,” he wrote. “Amongst the books were two copies of the New Testament, mutilated.” The two highly edited English New Testaments he discovered also came with a note indicating they had once been the property of Thomas Jefferson, who had used them to make an abridged version of the Gospels.

In his new role at the Smithsonian, Adler was well positioned to approach the Jefferson family and make inquiries about this rumored book. He learned that upon the 1892 death of Jefferson’s granddaughter Sarah Randolph, the redacted scripture had come into the possession of her daughter, Carolina Ramsey Randolph. After Adler made her an offer of $400, The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth joined the growing collections of the Smithsonian’s national museum.

Adler was not singularly responsible for delivering the book to the world, however.

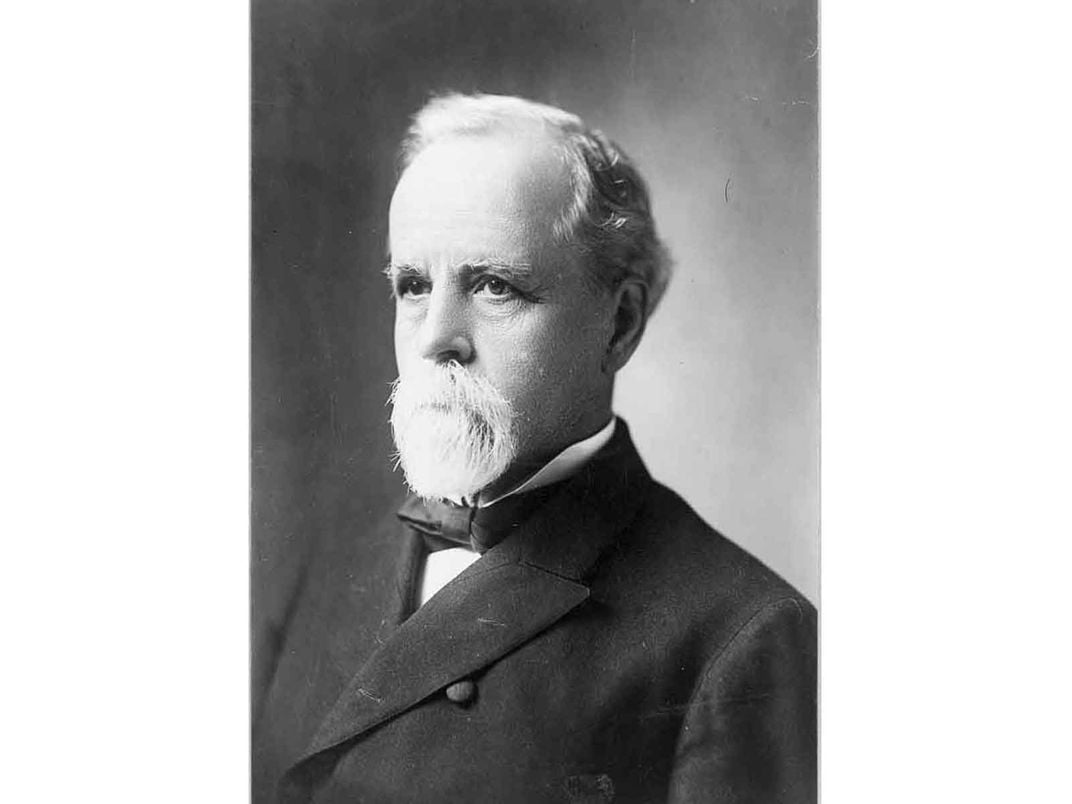

It would be Iowa Congressman John Fletcher Lacey who would begin to tell the story of the Jefferson Bible in the first spring of the new century. Lacey had been giving the collection of Jefferson’s books purchased by Congress in 1815 a “careful examination” when he thought to inquire about the whereabouts of the Bible.

In the search that followed, Lacey recounted that he nearly ransacked the Library of Congress, but the book was nowhere to be found. Only upon asking for the assistance of the Librarian of Congress did he learn that the volume would be found not in the shelves serving the Capitol, but elsewhere on the National Mall.

“A few days later,” an account published in 1904 recalled, “Mr. Lacey sought the librarian” Adler at the Smithsonian and “queried him concerning this mysterious volume.” Adler met with Lacey, showing him the Bible and before long Lacey had brought it to the attention of the House Committee on Printing, urging his colleagues to consider having this long-forgotten collection of Gospel extracts reproduced. With only a little persuasion, the next stage of the life of the Life and Morals had begun.

Lacey next set forth a bill calling for the U.S. government to fund the printing of 9,000 copies, 3,000 for use in the Senate, 6,000 for use in the House, to be reproduced “by photolithographic process,” and with an introduction “not to exceed 25 pages,” which would be written by Adler. The estimate expense for this project was $3,227. But the proposal sank.

When Lacey took to the House floor to defend the notion on May 10, 1902, his own party leveled pointed criticism. Fellow Republican Charles H. Grosvenor of Ohio had apparently not heard the news of the book’s discovery. When the Speaker of the House David B. Henderson announced the bill to be introduced, Grosvenor called out simply: “Mr. Speaker, what is this?”

“Congress has published all the works of Thomas Jefferson with the exception of this volume,” Lacey responded, “and that was not published because it was not then in the Congressional Library.”

Apparently dissatisfied with this response, Grosvenor asked again for his colleague to explain what exactly the book was, and why it was so important.

"Morals of Jesus of Nazareth as compiled by Thomas Jefferson,” Lacey answered. “It makes a small volume, compiled textually from the four Gospels. This is a work of which there is only one copy in the world; and should it be lost, it would be a very great loss.”

Grosvenor was not convinced. “Would the gentleman consent to put Dillingworth's spelling book as an appendix to the work?” he said mockingly, referring to a perennial text used by school children throughout the 19th century.

“That would be very amusing,” Lacey replied, “but this is really one of the most remarkable contributions of Thomas Jefferson.”

The sparring continued with Lacey defending his proposition. “The Government owns this manuscript, and it is the only copy in the world.”

“I wish it had never been found,” was Grosvenor’s final retort, while Lacey read into the record his appreciation of the book, and justification for its publication.

“Though it is a blue-penciled and expurgated New Testament, it has not been prepared in any irreverent spirit,” Lacey declared. “The result is a consolidation of the beautiful, pure teachings of the Saviour in a compact form, mingled with only so much of narrative as a Virginia lawyer would hold to be credible in those matter-of-fact days… No greater practical test of the worth of the tenets of the Christian religion could be made than the publication of this condensation by Mr. Jefferson.”

The bill passed, but the debate continued. Some members of Congress balked when they came to believe Lacey’s intention was to produce an annotated version of Jefferson’s redacted text. For those who had been initially ambivalent, the possibility of framing a historical document with an element that might amount to government-sponsored biblical criticism was too much to bear.

Meanwhile, news that the U.S. government would soon be in the Bible printing business ignited public alarm over Jefferson’s religious ideas such as had not been seen in nearly a century. “The so-called Jefferson Bible seems bound to make trouble," the Chicago Inter Ocean warned. "This is the more remarkable from the fact that it has been forgotten for nearly a century… So completely had the Jefferson Bible been forgotten that when the House of Representatives passed a resolution recently to print 9,000 copies comparatively few of the present generation knew that such a book existed.”

Now that they had been reminded, many of this generation wondered why this book should find publication at the public’s expense eight decades after its creation. Christian ministers were the loudest voices against the proposal. Across the country, all denominations opposed it.

Kerr Boyce Tupper of Philadelphia’s First Baptist Church immediately took to his pulpit to condemn the Jefferson Bible. Yet in doing so he took a unique tack. He argued that the U.S. government was Christian in character and should not abet such obviously un-Christian activities. “Ours is confessedly and conspicuously a Christian government,” he declared, “and Jefferson’s Bible, if rightly represented, is essentially an unchristian work.”

Elsewhere the prospect of the Jefferson Bible’s publication pit minister against minister. A meeting of the national Presbyterian Preacher’s Association convened to draft a statement of formal protest became mired in so much disagreement that it was forced to declare it had to “obtain further information before officially condemning the statesman's annotated book.” The group’s proposed resolution would have declared the publication of the Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth “a direct, public and powerful attack on the Christian religion” but the lively debate that ensued created only further confusion.

"If the people cannot look to us for unflagging vigilance in opposing the assailants of God’s Word,” the Rev. I. L. Overman argued, “to whom can they turn?”

In response, the Rev. Dr. J. Addison Henry made an appeal for pragmatism: "I have heard that the Jefferson work does not contain a single derogatory word against the Christian religion. Let us remember that ‘he who is not against us is for us.’ This so-called revised bible may help us.”

Members of the American Jewish community also saw the congressional printing of the Life and Morals problematic. The Jewish Exponent of Philadelphia published a statement of protest, and the journal Jewish Comment declared, “This is not the affair of government in this country and every Jew should be on the alert to safeguard against such acts of unwisdom.”

Among the most strident critics of the government’s proposed Bible printing project were not just ministers and rabbis, but publishers. “The preachers generally oppose the publication of the ‘Bible’ by the government, and so do the publishers, the latter wanting the job for themselves,” the Richmond Dispatch reported. “They wish to secure the printing privilege for general sale. They are, therefore, reinforcing the clergymen who are memorializing Congress to rescind its action.”

With both the religious establishment and the publishing industry agitating against Lacey’s well-meaning endeavor, members of Congress suddenly were on the defensive regarding a bill none anticipated would be controversial. “Mr. Jefferson has been unjustly criticized in regard to this very book, and in justice to him it should be made public,” the chairman of the House Committee on Printing, Rep. Joel Heatwole of Minnesota, told the Washington Post. He claimed that the idea of publication initially had not been that of the Committee, but of “frequent requests… for the publication of the book, these requests coming largely from ministers of the Gospel on the one hand, and people interested in the memory of Thomas Jefferson on the other hand.”

Perhaps missing the point that many critics simply did not want government involved in the business of publishing religious books, Heatwole added, “No one that examines this little volume will rise from his perusal without having a loftier idea of the teachings of the Saviour.”

Lacey, for his part, was astonished by the uproar. “There isn’t even a semi-colon in it that is not found in the Bible,” he said. Though many complaints had reached his office, he had also received requests for copies from preachers from all over the country. Yet ultimately it was the former that proved impossible to ignore.

Within two weeks of introducing the bill and speaking eloquently on its behalf, Lacey presented a resolution proposing to rescind its passage, and offering to pursue publication with private companies rather than the Government Printing Office. The odd coalition of those opposed to the publication seemed to have won the day.

In the end, however, the storm passed. Lacey’s bill to rescind approval of publication was never taken up by the House. Publication of the Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth by the U.S. Government Printing Office was scheduled for 1904.

Meanwhile, the bookish Adler did his best to stay out of the limelight and steer clear of the controversy. When the first copies of the edition published by Congress appeared, its title page read:

The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth :

Extracted textually from the Gospels in

Greek, Latin, French, and English

by Thomas Jefferson

With an Introduction

by Cyrus Adler

A bit abashed, Adler made sure that subsequent print runs would shorten the last line to simply “with an introduction.” He was proud of the work he had done to bring the Jefferson Bible to the world, but he had also seen the backlash publishing controversial works could bring. And besides, he said, “I felt that Jesus Christ and Thomas Jefferson were sufficient names for one title-page.”

Excerpt from The Jefferson Bible: A Biography by Peter Manseau. Copyright ©2020 by the Smithsonian Institution. Published by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/PManseau.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/PManseau.jpg)