Why We Have a Civic Responsibility to Protect Cultural Treasures During Wartime

With the recent deliberate destruction of cultural treasures in the Middle East, we remember the measures taken in the past to preserve our heritage

:focal(469x270:470x271)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/76/6b76924a-5f30-4009-956d-93ee9e601f09/4249052823web.jpg)

Sometime in the mid-6th century A.D., an unknown artist sculpted a beautiful figure standing nearly six feet tall out of the limestone in a man-made cave in northern China. Commissioned by a Buddhist emperor of the Northern Qi dynasty, the figure was a bodhisattva, representing an enlightened human being who delayed his own entry to paradise to help others achieve their own spiritual development. It joined an array of other sculptures, forming an underground temple of Buddhist iconography and signaled the regime’s desire for divine guidance and protection.

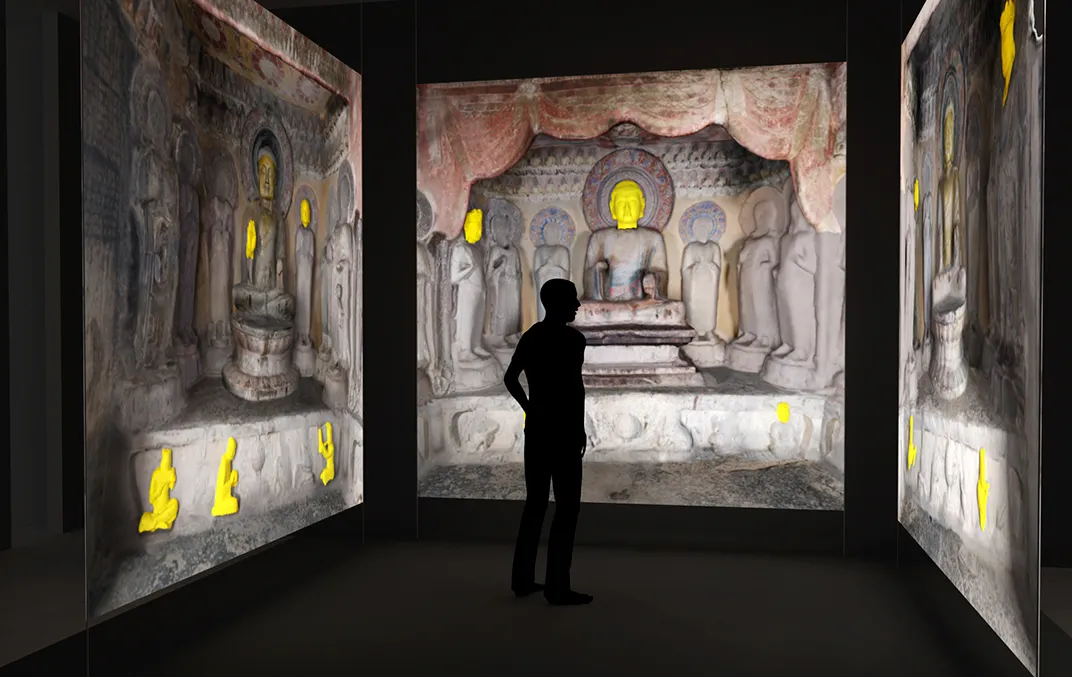

But neither enlightenment nor protection prevailed when in 1909 looters, encouraged by civil strife and lawlessness in China, started to cut and remove statues and sculpted heads from the temple cave and sell the treasures on the art market. The standing bodhisattva came to Paris in 1914, in the possession of Chinese immigrant and art dealer C.T. Loo and Swiss poet, collector and antiquities aficionado Charles Vignier. Two years later, they sold the piece to financier Eugene Meyer, who almost immediately offered to exhibit it at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. He and his journalist wife Agnes owned and loaned it for decades. The Meyers eventually bought the Washington Post and supported civic, educational and cultural causes. Agnes Meyer donated the statue to the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art in 1968. A few years ago, the standing bodhisattva helped anchor an exhibition, "Echos of the Past," organized by the Smithsonian and the University of Chicago, that included the statue’s appearance in a digitally reconstruction of the original Xiangtangshan cave before it was looted.

We know a lot about the sculpture from what we call provenance research—tracking the record of ownership of an artwork. It’s good practice, prescribed in the museum community to ensure that works are legally acquired. Museums generally operate according to a 1970 Unesco treaty that says that artworks illicitly obtained should be returned to their rightful owners. The U.S. and several other nations also seek to recover art work looted during the Nazi-era and return those as well—a practice initiated by the now well known “Monuments Men”—and women.

While museums are sometimes criticized for holding onto items acquired from other nations, their goal has been to preserve, exhibit and learn from them. It’s a noble, worthwhile and civic idea—that we of today might gain insight from understanding the past, and even be inspired by our heritage and that of others. Civic leaders generally support cultural heritage preservation and education as worthy social goals, though sometimes convincing politicians and officials that such efforts merit support from public coffers is not always easy. But actions undertaken in different parts of the world to destroy such heritage brings the basic mission of museums into strong relief.

The Taliban’s blowing up of the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001 was a shock, as has been the burning of medieval manuscripts in the libraries of Timbuktu and ISIS thugs taking sledgehammers to Akkadian and Assyrian sculptures in the Mosul museum. These heinous acts, condemned around the world, point to the material obliteration of history, of people’s diversity and often a society’s complex, multifaceted nuanced identity.

Extremists say that these objects have no value, but they cynically loot and sell what they can carry off, using such treasures to help finance further destruction. Cultural heritage, whether in the tangible form of monuments, mosques, temples, churches and collections or in the more intangible form of living customs, beliefs and practices is under attack as a strategic pillar of extremist warfare. It is a war on civilization itself—whether that be Islamic, Jewish, Christian, Hindu or Buddhist, eastern, western or indigenous.

One might be tempted to say, sacking and looting are the heritage of humankind in their own right—think the destruction of Solomon’s temple, the pillaging of Rome, the ransacking of Baghdad by the Mongols and the exploits of Conquistadors among the Aztecs and Incas. There are, of course, more modern examples.

Last year we celebrated the bicentennial of the Star Spangled Banner, held in the Smithsonian’s collection. The flag flew over Baltimore weeks after the British burned the U.S. Capitol, the White House and other public buildings in an effort to dispirit the young nation’s citizenry. Often, in modern warfare the scale of bombing and destruction by weaponry can make valued cultural heritage a casualty of inadvertent destruction.

The U.S. faced heavy criticism for the fire-bombing of the architecturally significant Dresden during World War II, but President Franklin Roosevelt and General Dwight Eisenhower recognized the need to try to protect heritage in the midst of the Allied invasion of Europe. Still there are times when a key decision makes a difference. Kyoto, home to much of Japanese imperial tradition and its most treasured sites, was high on the target list for the dropping of the atomic bomb. But U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson, even in an all-out war, recognized its cultural importance and vetoed that idea.

Cultural heritage, while targeted for destruction in war, can also be used to help heal after conflict and to reconcile people with their former enemies and their past. As Japan was recovering from the war and under U.S. occupation, it was no less a warrior than General Douglas MacArthur who supported the efforts of Japanese authorities to preserve their cultural treasures. In post-World War II Europe, Auschwitz, the largest concentration camp, became a memorial and museum to recognize and draw understanding from the Nazi effort to exterminate the Jewish people. The 1954 Hague Convention recognizing the value of heritage, demonstrated world-wide condemnation for the deliberate destruction of cultural property in armed conflict and military occupation, and a 1972 Unesco convention formalized an international regime for recognizing world heritage sites.

In the U.S. in the 1980s, American Indians and their culture, a century earlier marked by the government for destruction and assimilation, were celebrated with a national museum at the foot of the U.S. Capitol. In the 1990s, Robben Island, once the home of the infamous prison housing Nelson Mandela and his compatriots fighting against apartheid was turned into a museum for the new South Africa. Both prisoners and guards became docents, educating visitors about the era, and a site that had once drastically divided a population, helped to bring it together. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, the Mostar Bridge, commissioned by Suleiman the Magnificent had been destroyed in fighting between Croats and Muslims. The bridge had more than a roadway; it was a symbol of connection between the two communities and wiping it out served to divide them in conflict. In 2004 it was rebuilt, again serving to recognize a shared history.

The same year, the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre and museum opened in Rwanda, at the site of mass graves of victims of that genocide, and provided a means to encourage all citizens of that country, Hutu and Tutsi to avoid the racism and intolerance that led to that national tragedy. Not only museums and memorials, but heritage encapsulated in living traditions that once divided people can be used to bring them together. Unesco’s Slave Route project focused on how the African diaspora illustrated the perseverance of people and their cultures while enduring a most odious practice. The Smithsonian working with Yo-Yo Ma, the Aga Khan and Rajeev Sethi demonstrated how conflicts, forced migration and exploitation along the historic Silk Road were surmounted, and resulted in complex and creative cultural expressions in art, music, cuisine, fashion and ideas that connected people around the globe.

Cultural heritage teaches us things. It embodies knowledge of particular times about architecture, engineering, design, social structure, economy, craftsmanship and religious beliefs. It offers an appreciation of history, and lets us understand something about the way in which people lived. But heritage is not only about the past. Heritage is either forgotten and obscured, or articulated and valued in the present. It symbolizes how people think of themselves and others, including their predecessors and neighbors today. In that sense, cultural heritage teaches us about tolerance and respect for a diverse humanity. Saving heritage saves us from the foibles of arrogance, intolerance, prejudice toward and persecution of our fellow human beings. It reminds us of our better nature and like the standing bodhisattva, helps us all live in a more humane world.

The discussion continues in a program “Cultural Heritage: Conflict and Reconciliation” organized at the Smithsonian with the University of Chicago at the Freer Gallery’s Meyer Auditorium on April 17. A session featuring Irina Bokova, Director General of UNESCO, Emily Rafferty, the President of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mounir Bouchenaki, Director of the Arab Regional Centre for World Heritage, and Richard Kurin, interviewed by David Rubenstein, Smithsonian Regent and University of Chicago Trustee, and co-founder of The Carlyle Group. The event will be available via webcast.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/kurin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/76/6b76924a-5f30-4009-956d-93ee9e601f09/4249052823web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/89/bf892771-d99b-4d1f-9d33-8db4972e30fc/42-23829655.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5f/d7/5fd7b616-9c14-44f2-9716-1f340ceadbc1/42-29252364.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/e0/1de0fb10-ce3b-4547-a98a-ca9902e82071/42-64378043.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/kurin.png)