Why We Have to Play Catch-up Collecting the Portraits of Female Athletes

The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery is setting its sights on the future

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4e/4f/4e4f0ddc-1261-4162-b6cb-214bfaae9147/91t0038c1web.jpg)

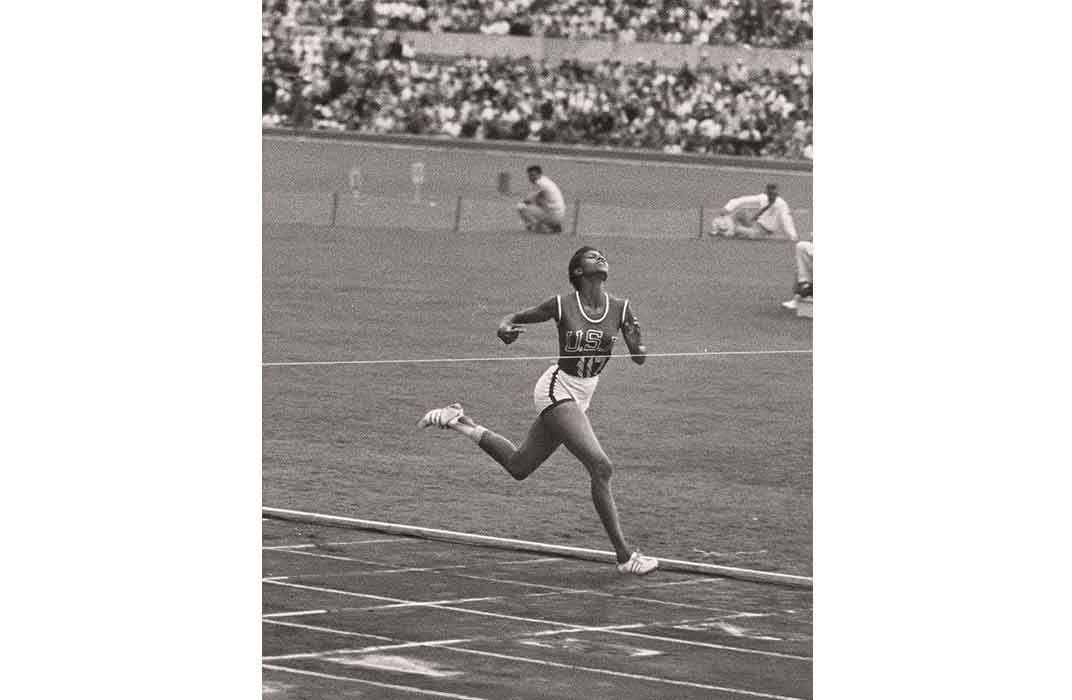

The history of American female Olympians has always been one of catch-up and perhaps it’s not too surprising that this also applies to portraiture. Most of the images of women athletes held in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery are photographs dating no earlier than 1970. Why? Because portraiture is always tied to advancements in history and art, and female Olympians—and their likenesses—were principally made possible through changes in civil rights legislation and the rise of photojournalism.

Another reason, is the history of the National Portrait Gallery and how the collection was created in the first place.

It was under President John F. Kennedy in 1962 that Congress decided to dedicate a museum to acquire the portraits of men and women who have made significant contributions to the development of America. The Portrait Gallery opened to the public in 1968 and—important for this conversation—it was not permitted to collect photographs until 1976, just 40 years ago. We also did not collect portraits of living people (other than U.S. presidents) for the museum's permanent collections until 2001.

Previously candidates had to have been dead 10 years and undergone the “test of time.” And finally, the history of American portraiture favored those who could vote; white men who owned land. So, we can perhaps be forgiven for now having to look back in order to truly reflect the words on the Great Seal of America: E Pluribus, Unum—Out of Many, One.

Returning to portraits of sporting champions, it is worth noting that the launch of the modern Olympic movement had a somewhat confused start. In 1896, 14 nations and 241 athletes—all men—came together to compete in Athens, but it was not until 1924 in Paris that the Olympics truly caught on as the recognized international event we know today. Women were first allowed to compete in only six sports: lawn tennis, golf, archery, figure skating, swimming and fencing consecutively.

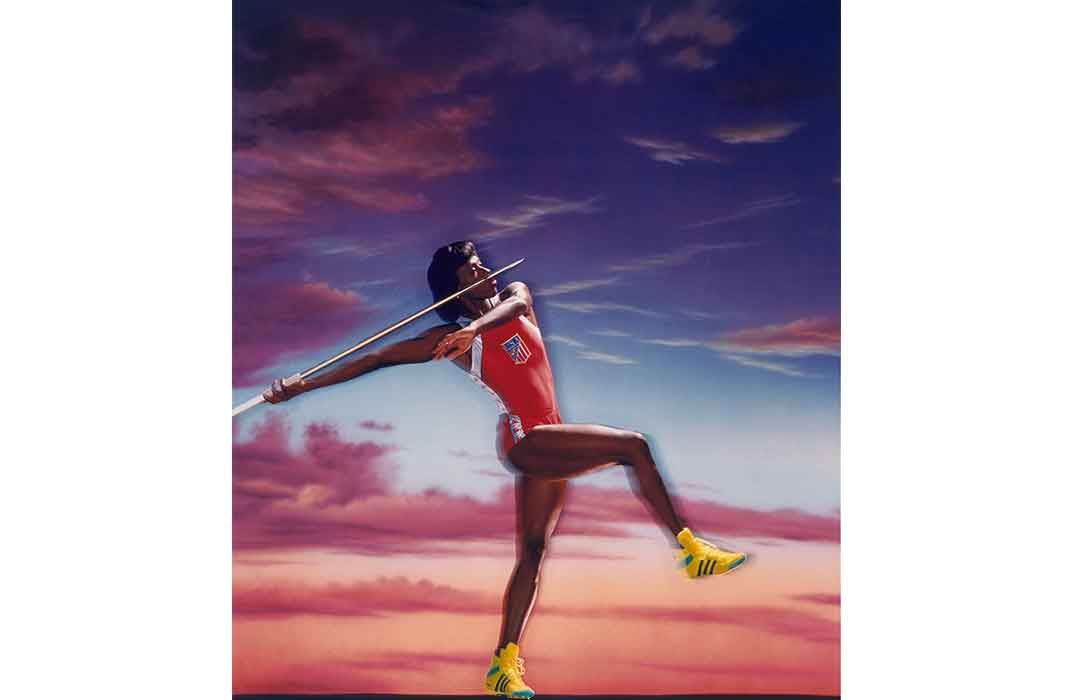

And when we reflect upon the achievements of past champions such as Jackie Joyner-Kersee, the most decorated woman in U.S. Olympic track and field history, it seems remarkable that athletics and gymnastics have only been open to women since 1928. Keep in mind, that 2016 is only the second time that woman are enrolled in all the sports thanks to the 2012 decision to allow female boxers to compete.

This history of absence is reflected in our national collection. Of the 13 women athletes whose portraits date prior to 1970, four are tennis players, four are ice skaters, three are swimmers, and two, Wilma Rudolph and "Babe” Didrikson, excelled at track and field.

Missing from the collection however, is golfer Margaret Abbot, the first woman to medal in the Olympics in 1900; Matilda Scott Howell, the first woman to win Olympic gold in 1904; and Elizabeth Robinson, the first woman to win gold in track and field in 1928.

The turning point for American female athletes began in 1964 with the passage of Title IX of the Civil Rights Act and that moment was further bolstered by the 1972 Title IX amendment to the Higher Education Act that would define sports as a component of “education” and prohibited institutions receiving federal funds to discriminate on the basis of gender.

According to the National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education, Title IX increased the number of women playing college level sports more than 600 percent, although women athletes still have significantly fewer opportunities than their male counterparts from scholarships to coaches and facilities.

In a similar vein, women earn on average of 23 percent less once they become professional, and depending on the sport, inequities can be much higher; players in WNBA earn only 2 percent of what men earn in the NBA. Similarly although almost a quarter of the 2016 Team USA represent a racial minority—the most diverse Olympic team in history—minority women are a much smaller subset of the whole. The arts, I’m afraid, tell a similar story. Of all the athletes found in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection search, less than seven percent depict women.

While the Ancients famously commemorated their Olympic champions by means of profiles created on sculptures, ceramics and minted coins, around the turn of the 20th century photojournalism—the combination of documenting current events with thrilling photography that could be easily distributed via printing technology—was the main form of sports portraiture. A significant gender bias, however, has existed with regards to depicting women athletes; with the most notable example being Sports Illustrated that despite having launched in 1964 has featured women athletes less than five percent on their covers. How wonderful then to hear that they, too, are becoming more inclusive with the news that this week’s magazine cover features Michael Phelps, Katie Ledecky and Simone Biles wearing their combined total of 14 medals from the Rio Olympic games.

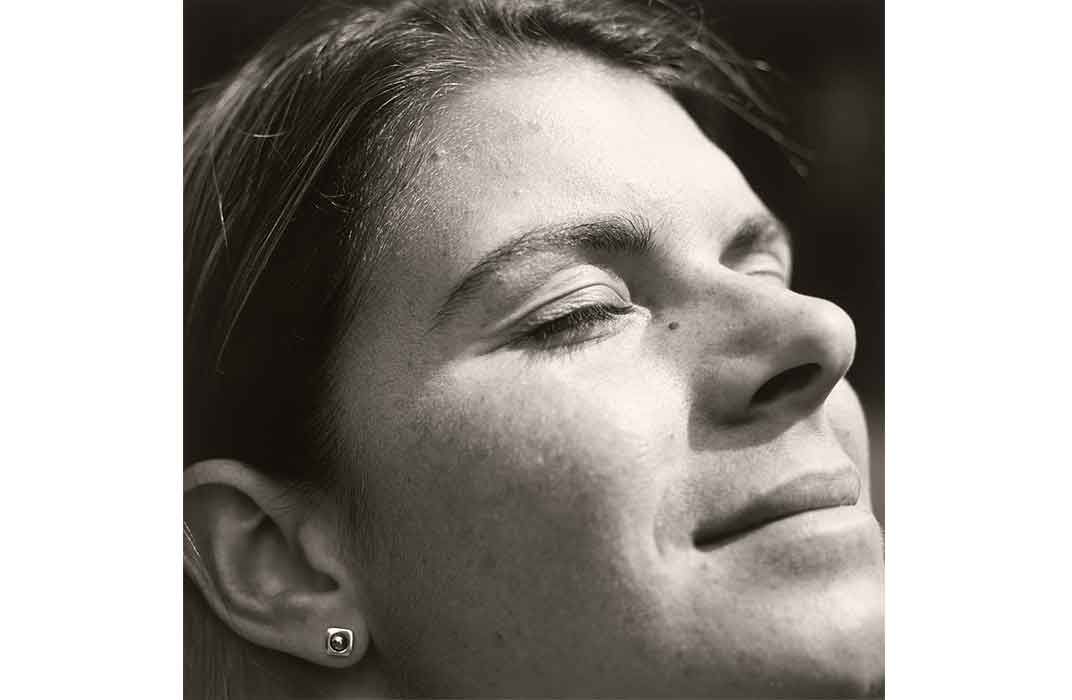

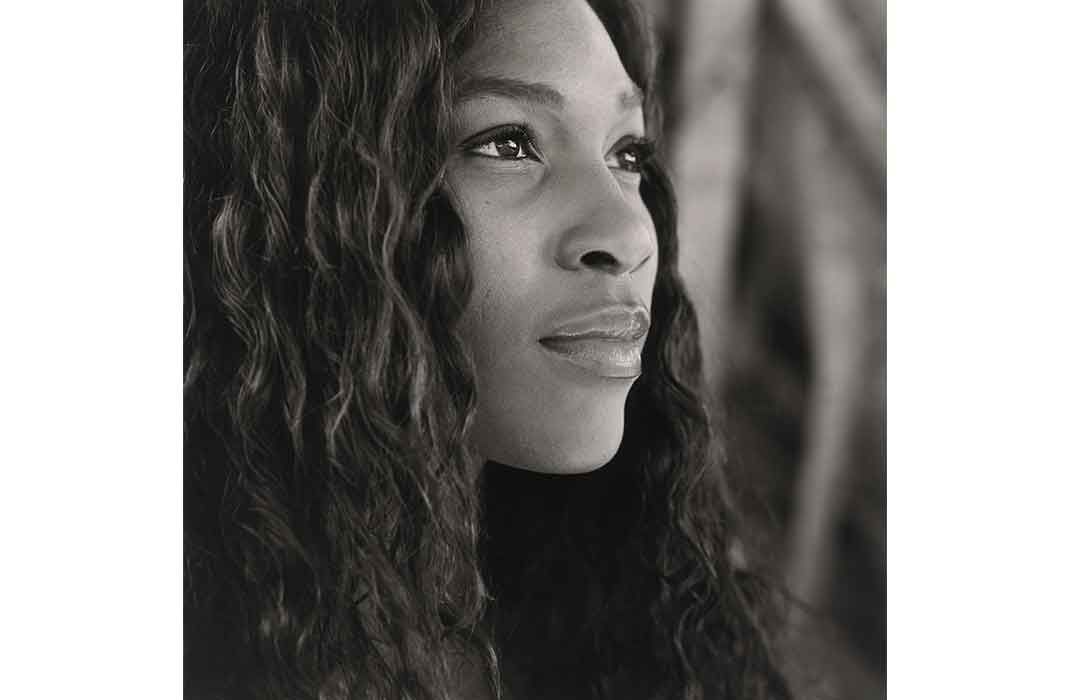

Despite the historical challenges we are thankful for the keen eye of a range of artists who first got behind the camera for TIME magazine, Sports Illustrated, ESPN and other popular publications that the national collection now includes fabulous portraits of such champions as figure skaters Dorothy Hamill and Debi Thomas, soccer star Mia Hamm, and tennis greats Billie Jean King, Chris Evert, Venus Williams and Serena Williams.

Collecting images of past athletes proves difficult as many were never recognized in their time with any sort of visual documentation. However amazing finds are still possible. In 2015, for example, we were overjoyed to acquire a very rare albumen silver print of Aaron Molyneaux Hewlett by George K. Warren that dates to 1865. Hewlett, a professional boxer from Brooklyn, became the first African-American appointed to the Harvard University faculty and the first superintendent of physical education in American higher education.

The future looks brighter. As sportswomen advance to equal their male peers, and photojournalists become more inclusive with regards to whom they feature, the National Portrait Gallery looks forward to adding more amazing women—and men—to the nation’s family album.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/KSajet_portrait_orange_1.13.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/44/09/4409c127-9311-465e-bffa-2ffe8b103426/b4000026cweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/KSajet_portrait_orange_1.13.JPG)