Why We Missed America’s National Treasures During the Shutdown

The Smithsonian’s Richard Kurin reflects on the recent shutdown and the icons that have shaped American history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131022092037around-the-mall-shutdown-lessons-thumb.jpg)

The doors of the Smithsonian’s museums were recently shuttered during the debt crisis and shutdown of the United States government. Americans who had long ago planned their trips to the nation’s capital, as well as foreign tourists and school children, arrived only to find signs barring them from entry “due to the government shutdown.” Elsewhere in the country, visitors to national parks, historic monuments and memorials, and even websites found a similar message. The shutdown and debt ceiling crisis brought home to many Americans the fragility of our democracy. That sense of loss and then relief prompts a reflection on why these items came to be significant and how they became, sometimes surprisingly, even precariously, enshrined as icons of our American experience.

The National Zoo’s panda cub born on August 23, 2013, weighed just three pounds when the camera inside the enclosure went dark on October 1. But the cub’s mother Mei Xiang remained diligent in her maternal care, and the Zoo’s animal handlers and veterinarians continued their expert vigilance—so that when the panda cam came back on, the public was delighted to see the little cub was not only healthy, but had gained two pounds and was noticeably more mature. Tens of thousands of viewers rushed to the website on October 18, crashing the system over and over again. The next day, the Zoo’s celebrated reopening made newspaper headlines across the nation.

The excitement reminded me of another type of opening, when the pandas made their original appearance at the Zoo during the Nixon administration. Those first pandas, Hsing-Hsing and Ling-Ling, came to Washington in 1972 because Nixon was seeking a diplomatic opening of a relationship between the United States and the Communist government of the People’s Republic of China. As part of a mutual exchange of gifts, the Chinese offered the pandas to the United States. And we in turn, gave the Chinese a pair of musk oxen, named Milton and Matilda. This was zoological diplomacy at its most elaborate—the State Department had carefully brokered the deal, ruling out other creatures, like the bald eagle, as unsuitable. The eagle, it determined, was too closely associated with our beloved national symbol. Bears were symbolic of Russia, and mountain lions signaled too much aggression. In any case, I think we got the better of the deal. The pandas became instant celebrities and when they took up residence at the Zoo, they transcended their diplomatic role, becoming instead the much-loved personalities and evolving over time into ambassadors of species and ecosystem conservation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dd/ef/ddefb698-e345-497e-9da3-4757ff27a897/libertysm.jpg)

The Statue of Liberty, so familiar to us in New York Harbor as a symbol of freedom, is a historic beacon to immigrants, and a tourist destination, but it didn’t start out that way. Its sculptor and cheerleader Frédéric Bartholdi initially designed the large statue for the Suez Canal in Egypt. But finding a lack of interest there, Bartholdi modified and repurposed it for a French effort to celebrate friendship with America in celebration of the U.S. centennial. The sculptor found an ideal site for it in New York, and while French citizens enthusiastically donated their money to fabricate the statue, American fundraising for the statue’s land, base and foundation faltered. Hoping to persuade Congress to support the project, Bartholdi sent a scale model of Liberty from Paris to Washington, where it was installed in the Capitol Rotunda. But Congress wasn’t swayed.

Other U.S. cities sought the statue. Newspaper publisher and grateful immigrant Joseph Pulitzer eventually took up the cause—donations large and small at last rolled in. In 1886, with Thomas Edison’s newly invented electric lights installed in Liberty’s torch, President Grover Cleveland pulled the rope to unveil her face, and the Statue of Liberty was open. It was some 17 years later, as a massive influx of immigration was stirring civic debate, that the poem by Emma Lazarus with its famed phrase “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to be free” was posthumously added as an inscription on its base. It’s wonderful to be able to visit the Statue in New York again every day, and Bartholdi’s model too, is here in Washington, residing on the second floor of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

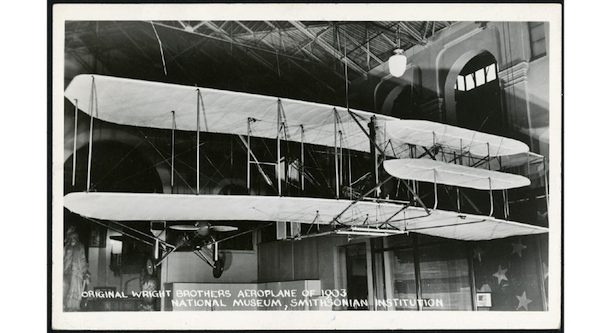

The shutdown of the immensely popular National Air and Space Museum came at a particularly unfortunate time. The museum was temporarily displaying, through October 22, Leonardo da Vinci’s handwritten and illustrated Codex on the Flight of Birds, a rare and unusual loan from the people of Italy. Tens of thousands of U.S. citizens missed out on an opportunity to see this amazing Renaissance document from the early 16th century—an experience made all the more poignant because it was put on display alongside the Wright brothers’ Kitty Hawk Flyer. Almost like the fulfillment of da Vinci’s musing, this airplane opened the skies to humans in an unprecedented way after a series of flights on North Carolina’s Outer Banks on December 17, 1903. The Flyer was the first heavier than air, self-powered, piloted craft to exhibit controlled, sustained flight. It took on irreparable damage that day and never flew again. Few realize, however, that a disagreement between Orville Wright and the Smithsonian nearly prevented the flyer from ever coming to Washington. Orville was rightly offended by the incorrect labeling of another airplane on view at the Smithsonian. The label claimed the honor of first in flight went to an aircraft invented by Samuel P. Langley, a former Secretary of the Institution. The dispute lasted for decades and the Wright Flyer went to London and would have stayed there had not Orville Wright and the Smithsonian finally settled their differences in 1948 and the little aircraft that changed history came to Washington.

The Star-Spangled Banner on view at the National Museum of American History reminds us of how our government and nation was almost shutdown by war and invasion. In August 1814, British troops, had routed the local militia, invaded Washington, burned the Capitol, the White House and other public buildings and was advancing on to Baltimore, a strategic target with its privateers and port on the Chesapeake Bay. British ships pounded Fort McHenry which defended the city from invasion. Rockets and bombs burst overhead through the night in a vicious assault—but the troops and the fortifications held strong. And on September 14, Francis Scott Key, a lawyer and poet saw the huge American garrison flag still flying in the “dawn’s early light,” and penned the words that once set to music became our national anthem. The flag itself was paraded and celebrated almost to destruction throughout the 19th century; people clipped pieces of its red, white and blue threadbare wool cloth as souvenirs. Finally, in 1907, the flag was sent to the Smithsonian for safekeeping. We’ve cared for it well, using support from the federal government and donors like Kenneth Behring, Ralph Lauren, and others to carefully restore it and house it in an environmentally controlled chamber—but when visitors see the flag and learn its story, they soon realize how tenuous our country’s hold on its freedom really was 200 years ago.

The basic principle of democracy—self-government, was spelled out in the Declaration of Independence that affirmed the founding of the United States on July 4, 1776. The Congress had John Dunlap print a broadside version of the Declaration, which was quickly and widely distributed. In the following months, a carefully hand-lettered version on vellum was signed by members of the Congress, including its president, John Hancock. This document is called the engrossed version. Lacking a permanent home during the Revolutionary War, the document traveled with Congress so that it could be safeguarded from the British. The engrossed version faded over the ensuing decades, and fearing its loss, the government had printer William Stone make a replica by literally pulling traces of ink off of the original to make a new engraving. Stone was ordered to print 200 copies so that yet another generation of Americans could understand the basis of nationhood. In 1823, he made 201—which included a copy for himself; that extra one was later donated by his family to the Smithsonian and is now in the collections of the American history museum. The faded engrossed version is on exhibit at the National Archives, re-opened for all to enjoy.

The Declaration of Independence has been preserved, enshrined, and reproduced. Its display continues to inspire visitors—and though its fragility might be taken as a metaphor for the fragility of the principles of democracy and freedom it represents, it also reminds us that democracy requires persistent care. Places like our museums, galleries, archives, libraries, national parks and historic sites provide the spaces in which the American people, no matter how divided on one or another issue of the day, can find inspiration in a rich, shared, and nuanced national heritage.

The Smithsonian’s History of America in 101 Objects, Penguin Press, is out this month.