Why Is This Year’s Passover Seder Different From All Other Years’?

A Smithsonian folklorist examines Jewish humor in the midst of a pandemic

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/31/70/3170c099-2c6a-4832-9ddb-d50191baef81/gettyimages-607352076.jpg)

The eight-day Jewish holiday of Passover (Pesach) begins this year after sundown on Wednesday. The first night’s ritual meal, known as a seder, typically brings together extended family and usually some friends. The youngest person at the table sings four questions, all of which ask what makes the night different from all other nights. The irony is that due to the coronavirus pandemic, this year’s seder will have to be different from all other years.

The story of Passover may sound terribly solemn to the uninitiated. After all, it tells how the Jewish people were enslaved in Egypt for some 200 years until God, on their behalf, unleashed ten terrible plagues, including frogs, lice, boils and locusts. Jews escaped the tenth plague—the killing of firstborn sons in each household—by marking their door posts with the blood of a sacrificial lamb. Seeing this mark, the Angel of Death “passed over” those houses and spared its inhabitants. However, before they could safely settle in their homeland of Canaan, the Jews endured another 40 years of wandering in a desert wilderness. We can read about all of these grim details in the Old Testament's Book of Exodus.

In contrast to the austerity and tribulations of the Passover story, the seder affords an opportunity to celebrate communally. As Ruth Marcus in the Washington Post explains, “a Passover Seder is the ultimate antithesis of social distancing. We are commanded to come together to retell the Passover story, to share it with our children, even those too young to comprehend.” Seder in Hebrew means order, so almost everything about the occasion is prescribed with rituals.

For instance, the meal offers an abundance of food, including matzo ball soup and gefilte fish, two staples of Eastern European Jewish cuisine. There’s an abundance of drink, including no less than four prescribed cups of wine. There’s an abundance of singing, including songs about numbers (Echad Mi Yodea, or “who knows one”), songs about animals (Chad Gadya, or “one little goat”), and a song to express one’s appreciation to God (Dayenu, or “it would have been enough”). There’s also a treasure hunt for a hidden piece of matzah. And all of this is supposed to be done while reclining, as part of the informality and relaxation of the occasion.

But how will Jews observe such communal traditions this year amid the coronavirus pandemic? Large gatherings of people packed around a table to share food and drink are simply not kosher. Most families will have to isolate themselves, but perhaps extend the rituals to others through a virtual presence. Although the direct use of electronic devices at the seder is normally prohibited among more observant Jews, most (but not all) rabbis are allowing for a streaming seder, especially if a virtual assistant like Siri or Alexa can activate the stream.

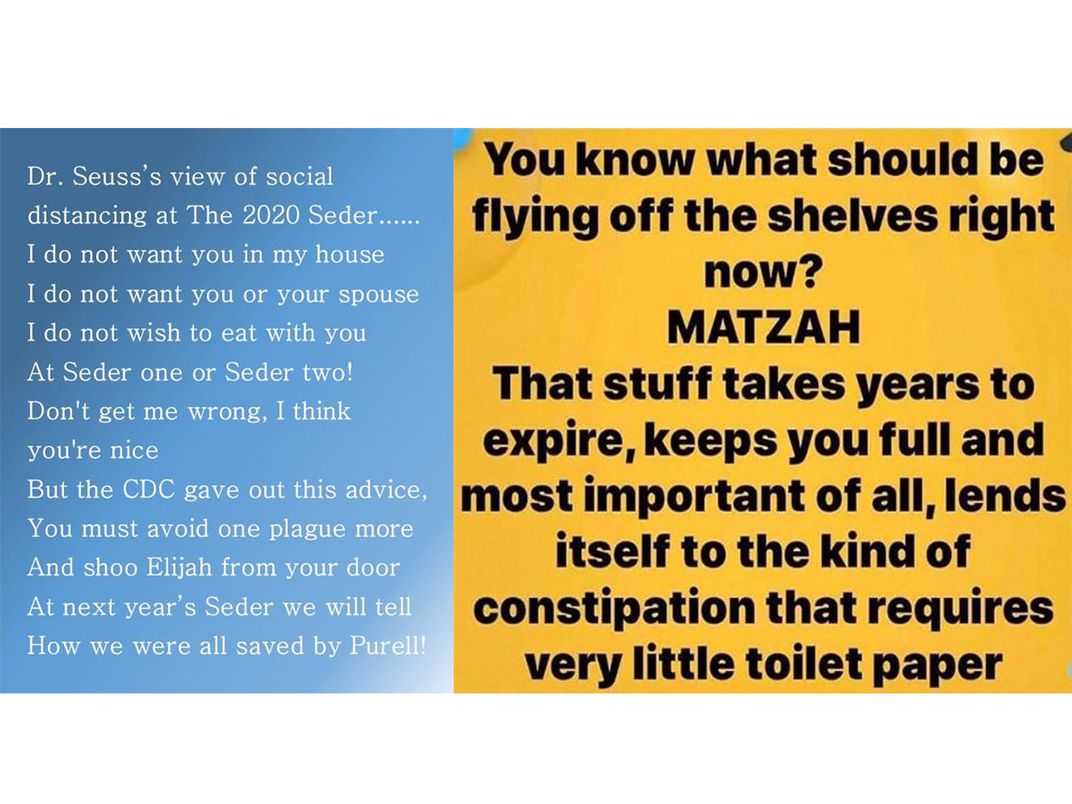

Streaming aside, what is of great interest to folklorists are the ways in which folk groups—be they religious, regional, racial, ethnic, or occupational—seek to maintain their longstanding traditions when threatened by adversity and upheaval. Perfect examples are the folk humor, such as the jokes and cartoons that are being widely shared by Jews during Passover preparations.

One comes in the form of a mock open letter to Dr. Anthony Fauci, seeking advice on how to manage the seder this year. Before asking questions about how to disinfect a seder plate or if “wandering in the desert [would] be advisable at this time,” the letter-writer informs Fauci, “You’re busy saving the world on four hours of sleep (Dayenu, am I right?), and I’m busy watching C-SPAN, eating Lucky Charms by the fistful, and not bothering to change from my daytime athleisure wear to my nighttime athleisure wear.”

Another joke in the form of a memo “issued by a family contemplating the season,” highlights a series of changes made necessary by the pandemic. For instance, instead of the traditional salt water on the seder plate to symbolize the tears and sweat of enslavement, “you should be able to cry your own salt water tears.” Children under five will be allowed to attend, but only if “they are entirely wrapped in plastic.” And instead of the prescribed four cups of wine, the Almighty has allowed us to drink eight cups.

What is revealed by these Jewish jokes about Passover seems less about the pandemic itself, and more about the patterns and traditions of Jewish humor. Folklorists who have studied Jewish jokes have noted their reliance on self-deprecating humor, in which the joke-tellers make fun both of themselves (eating Lucky Charms and needing eight cups of wine) and of their Jewishness, sometimes even resorting to anti-Semitic stereotypes. Think of Jack Benny (born Benjamin Kubelsky) who continuously joked about his stinginess with money. Or Sarah Silverman, who jokes about who is responsible for the death of Jesus Christ. Or Jerry Seinfeld, whose “greatest” Jewish joke plays on the belief that Jews are always complaining, or kvetching. By telling such jokes, Jews may be able to take some ownership of these stereotypes and thereby illustrate some of their absurdity.

This last feature seems to best explain the style of Jewish humor amid a pandemic. The coronavirus jokes may help to relieve anxiety, in part by joking about such a serious topic. And the Passover humor may help to build solidarity among members of this particular religious group. But I think it’s distinctively Jewish humor to comment on the irony that a holiday about plagues could be canceled or curtailed because of a plague. That’s kvetching at its finest.

This post originally appeared on the website of the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.

James Deutsch is a curator at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. He has participated in Seders in a dozen states and several foreign countries but has never tasted a matzo ball soup as delicious as his mother’s.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)