When the Last of the Great Auks Died, It Was by the Crush of a Fisherman’s Boot

Birds once plentiful and abundant, are the subject of a new exhibition at the Natural History Museum

In June of 1840, three sailors hailing from the Scottish island of St. Kilda landed on the craggy ledges of a nearby seastack, known as Stac-an-Armin. As they climbed up the rock, they spotted a peculiar bird that stood head and shoulders above the puffins and gulls and other seabirds.

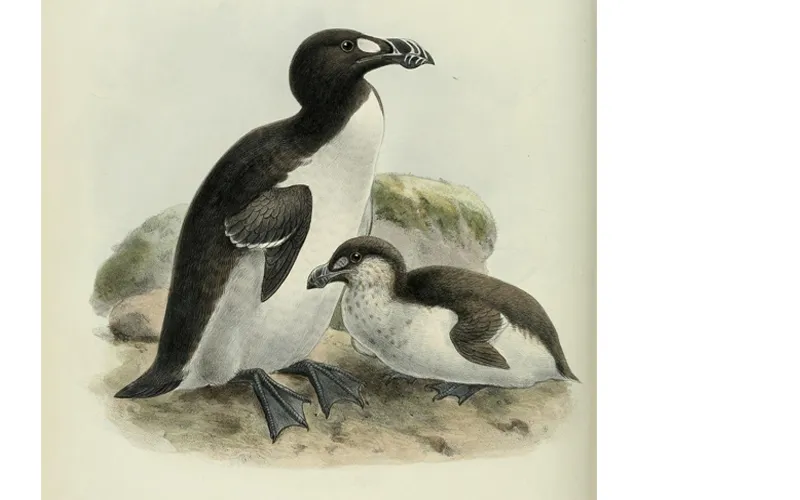

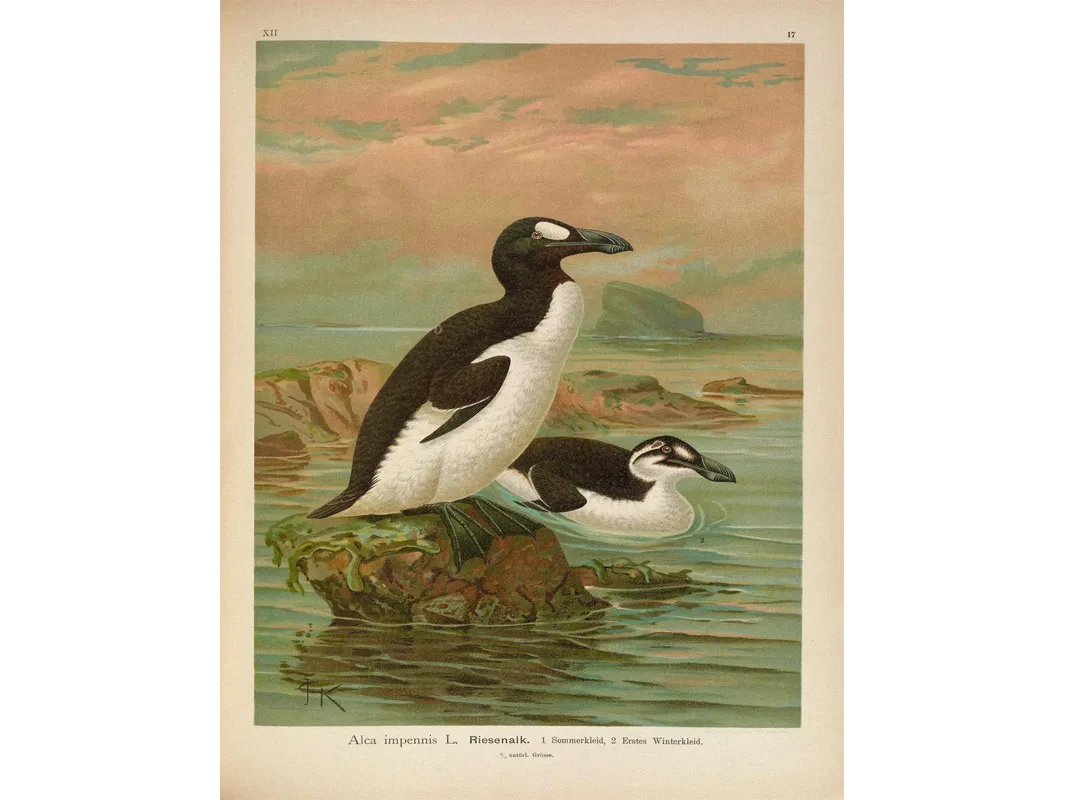

The scruffy animal’s proportions were bizarre—just under three feet tall with awkward and small wings that rendered it flightless, and a hooked beak that was almost as large as its head. Its black and white plumage had earned it the title the “original penguin,” but it looked more like a Dr. Seuss cartoon.

The sailors watched as the bird, a Great Auk, waddled clumsily along. Agile in the water, the unusual creature was defenseless against humans on land, and its ineptitude made it an easy target “Prophet-like that lone one stood,” one of the men later said of the encounter.

Perhaps the men enjoyed the thrill of the hunt, or perhaps they realized its meat and feathers were incredibly valuable. In any case, they abducted the bird, tying its legs together and taking it back to their ship. For three days, the sailors kept the Great Auk alive, but on the fourth, during a terrible storm, the sailors grew fearful and superstitious. Condemning it as “a maelstrom-conjuring witch,” they stoned it to death.

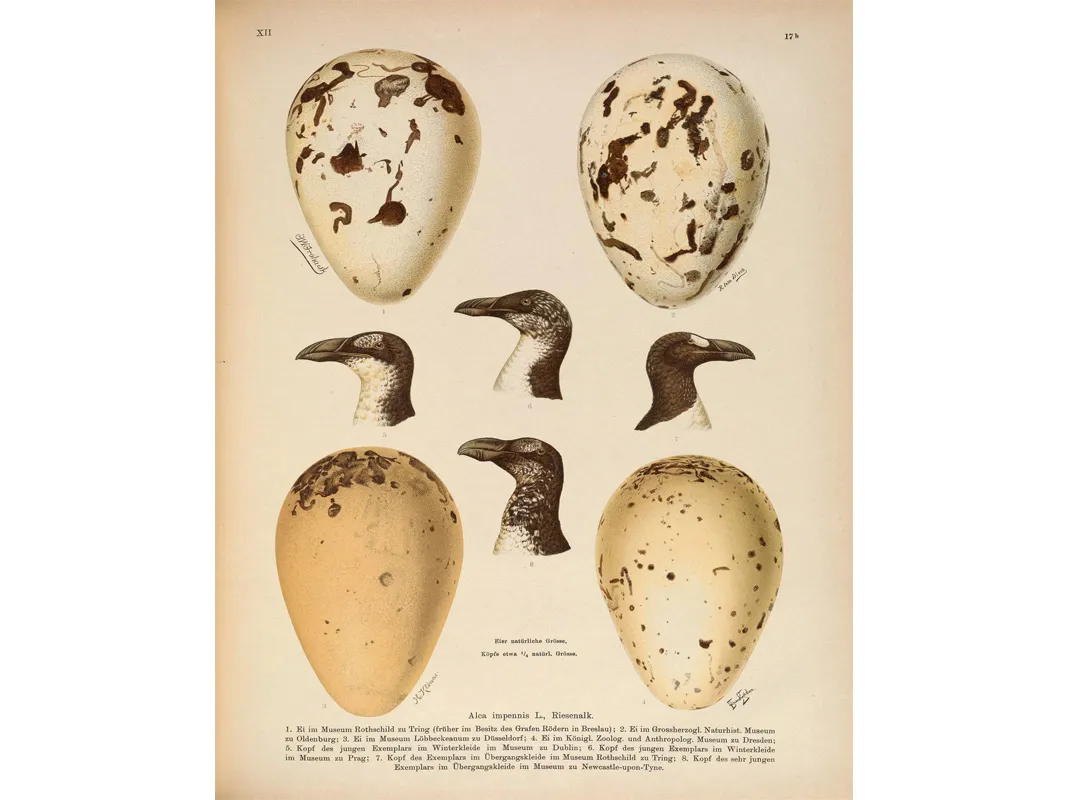

It was the last of its kind to ever be seen on the British Isles. Four years later, the Great Auk vanished from the world entirely when fishermen hunted down the last pair on the shores of Eldey Island, off the coast of Iceland. The men spotted the mates in the distance and attacked, catching and killing the birds as they fled for safety. The female had been incubating an egg, but in the race to catch the adults, one of the fishermen crushed it with his boot, stamping out the species for good.

Now the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History is paying homage to the Great Auk and other extinct birds including the Heath Hen, Carolina Parakeet, and Martha, the last Passenger Pigeon, in a new exhibition from the Smithsonian Libraries called “Once There Were Billions: Vanished Birds of North America.” Featuring the Great Auk as a cautionary tale, the show—which includes taxidermy specimens from the collections and several antiquarian books like John James Audubon's The Birds of America—paints a striking picture of the detrimental effects humans can have on their environment.

The Great Auk’s grim fate had been predicted as far back as 1785 by explorer George Cartwright. “A boat came in from Funk Island laden with birds, chiefly penguins [Great Auks],” wrote Cartwright. “But it has been customary of late years, for several crews of men to live all summer on that island, for the sole purpose of killing birds for the sake of their feathers, the destruction which they have made is incredible. If a stop is not soon put to that practice, the whole breed will be diminished to almost nothing.”

Once widely distributed across the north Atlantic seas, Great Auks roosted mostly in the water except during breeding season when the birds inhabited only a select few islands ranging from Newfoundland in the west to Norway in the east. Prior to the 16th century, the species was so abundant that colonies consisting of hundreds of thousands packed the shores during the month-long breeding season. The Little Ice Age of the 16th to the 19th centuries slightly reduced their numbers and territory when their breeding islands became accessible to polar bears, but even with their natural predators encroaching upon their territory, they were a robust species.

It was not until the mid-16th century when European sailors began to explore the seas, harvesting the eggs of nesting adults that the Great Auk faced imminent danger. “Overharvesting by people doomed the species to extinction,” says Helen James, curator of the exhibition and a research zoologist at the Natural History Museum. “Living in the north Atlantic where there were plenty of sailors and fishermen at sea over the centuries, and having the habit of breeding colonially on only a small number of islands, was a lethal combination of traits for the Great Auk.”

The auks required very specific nesting conditions that restricted them to a small number of islands. They showed a preference for Funk Island, off the coast of Newfoundland, and Geirfuglasker and Eldey islands, off the coast of Iceland, and St. Kilda, all of which provided rocky terrain and sloping shorelines with access to the seashore. A sailor wrote that in 1718, Funk Island was so populated by Great Auks that “a man could not go ashore upon those islands without boots, for otherwise they would spoil his legs, that they were entirely covered with those fowls, so close that a man could not put his foot between them.”

Funk Island also happened to be favored as a stop for sailors heading towards the end of their transatlantic journeys. With provisions dwindling and a craving for fresh meat making them ravenous, the sailors would herd hundreds of the birds into their boats. In 1534, French explorer Jacques Cartier wrote, “in less than half an hour we filled two boats full of them, as if they had been stones, so that besides them which we did not eat fresh, every ship did powder and salt five or six barrels full of them.” Likewise, in 1622, Captain Richard Whitbourne said sailors harvested the auks “by hundreds at a time as if God had made the innocency of so poor a creature to become such an admirable instrument for the sustenation of Man.”

Hunting of the Great Auk was not a new practice. As humans first began settling in Scandinavia and Icelandic territories as far back as 6,000 years ago, Great Auks were estimated to be in the millions. A 4,000-year-old burial site in Newfoundland contained no less than 200 Great Auk beaks that were attached to ceremonial clothing, suggesting they were important to Maritime Archaic people. Similarly, their bones and beaks have turned up in ancient graves of Native Americans as well as paleolithic Europeans.

The Great Auk was wanted for more than its meat. Its feathers, fat, oil, and eggs made the original penguin increasingly valuable. The down industry in particular helped propel the bird to extinction. After exhausting its supply of eider duck feathers in 1760 (also due to overhunting), feather companies sent crews to Great Auk nesting grounds on Funk Island. The birds were harvested every spring until, by 1810, every last bird on the island was killed.

Some conservation attempts were made in order to protect the bird’s future. A petition was drafted to help protect the bird, and in 1775 the Nova Scotian government asked the parliament of Great Britain to ban the killing of auks. The petition was granted; anyone caught killing the auks for feathers or taking their eggs was beaten in public. However, fishermen were still allowed to kill the auks if their meat was used as bait.

Despite the penalties for killing Great Auks, the birds once endangered, became a valuable commodity, with collectors willing to pay as much as $16—the equivalent of nearly a year's wage for a skilled worker at the time—for a single specimen.

Specimens of the Great Auk are now preserved in museums around the world, including the Smithsonian. But even those are rare, with only about 80 taxidermied specimens in existence.

The exhibition,“Once there Were Billions: Vanished Birds of North America,” produced by Smithsonian Libraries, is on view through October 2015 at the National Museum of Natural History.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-07-10_at_9.57.27_AM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a4/12/a412f158-c771-4565-865e-c0a2fc61229a/auk1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/cf/c7cf7e41-d722-4857-b04b-dfd2e435326e/carrier_pigeon.jpg)