This Woeful Wipeout Made Evel Knievel an Instant Legend

In 1967, a bone-shattering spill at Caesars Palace spawned a career in self-endangerment

:focal(990x295:991x296)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/3b/823bf9ce-a43f-487c-ba0d-76241b71f855/evel1.jpg)

Whether or not you consider yourself a fan of stunt biking, it is safe to assume the name Evel Knievel rings a bell. A prototype of American recklessness and audacity, Knievel is remembered not only for his successful long-distance jumps, but also for his crushing, can’t-look-away failures. One of these wipeouts, which took place on the grounds of the (just-opened) Caesars Palace hotel and casino in 1967 Las Vegas, stands out: this incident, which left Knievel battered and bedridden, wound up catapulting him into the international spotlight.

It was Friday, December 31, the brink of a new year in Cold War-worn America, when the charismatic but then little-known biker attempted a ramp-to-ramp jump of the signature fountains at Caesars Palace. (They had caught his eye the previous month, when he was in town to see a boxing match.) At 141 feet, the horizontal distance he needed to traverse while airborne to make it across the water would have intimidated anyone, especially bearing in mind the weight and power limitations of motorbikes in that era. Knievel, though, was the picture of steely stoicism. Stern-faced, he sat atop a red, white and blue Triumph-brand cycle emblazoned with the motto “Color me lucky,” and sported a patriotic jumpsuit to match.

As Knievel accelerated along the lengthy takeoff ramp, the dense crowd gathered to see the spectacle held its breath. Then, for a surreal couple seconds, the motorcycle man glided through the clear air, the jets of the Palace fountains framing him in an image of pure daredevil glory. A moment later, he hit the landing ramp, his feat seemingly a smash success. But all did not go according to plan. He had just barely made it onto the second ramp, the rear wheel of the Triumph snagging on the edge as he touched down. This threw Knievel fatefully off-balance.

Hoorays gave way to horror as the biker flipped headfirst over his handlebars, his body slamming against the asphalt of the Caesars parking lot and rolling several times before stopping. His rider-less cycle spun out of control and skidded away. Concussed and with severe fractures in his pelvis, femur, wrist and ankles, Knievel was rushed to the hospital, where he passed the next month recovering. A rumor circulated that he spent fully 29 days comatose, which in all likelihood was not the case. But belief in that factoid added to fans’ exuberance when Knievel finally revealed himself, alive and on the mend, to his adoring public.

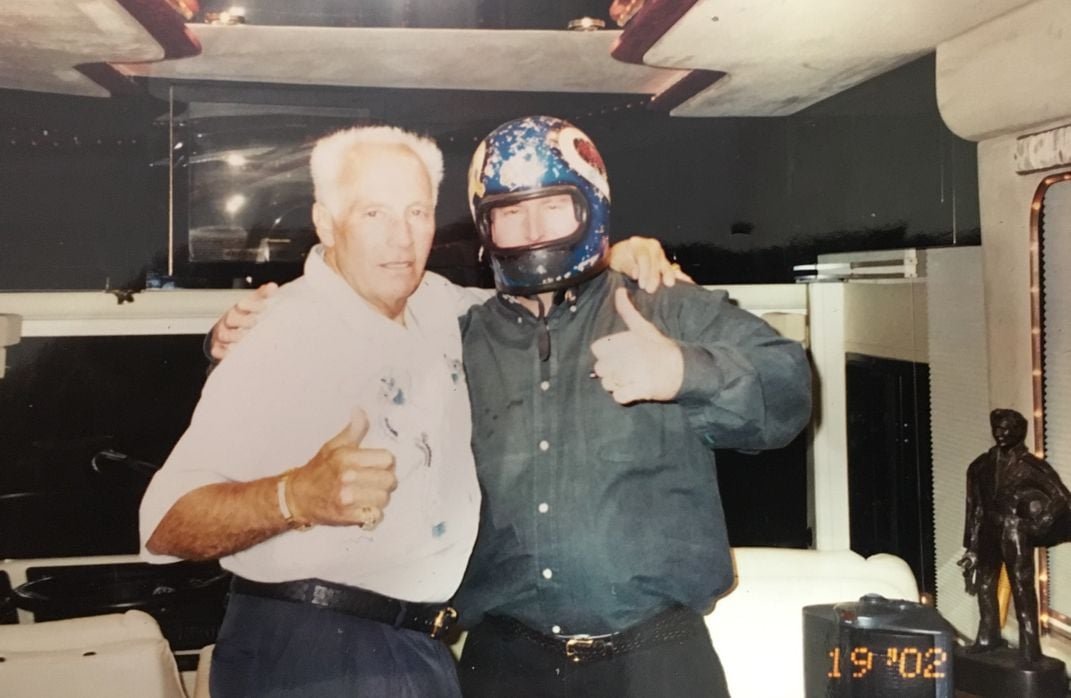

“This made him a superstar,” says Joey Taff, a close friend of Knievel’s and his sometime de facto PR spokesman. It was thanks to a persuasive letter Taff composed in 1993 that one of Knievel’s trademark jumpsuits and the XR-750 Harley-Davidson that became his signature ride found their way into the Smithsonian’s collections.

“Everybody in the world was praying for him,” Taff recalls with excited hyperbole. “All over the world, everybody was praying for this crazy guy nobody had ever heard of, Evel Knievel.” What began as an incredibly ill omen for 1968—and indeed, it was a terrible year for the United States—turned into a glimmer of hope for Americans and others as Evel pulled through. “He lived, and he walked,” Taff says. “Coming out of the hospital in a wheelchair, it was just huge all over the news. By that time, he was a household name.”

“He was both a daredevil and a showman,” says Roger White, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, “an action hero come to life. Whatever he did, he expanded it to incredible lengths, and exceeded incredible limits. He’s earned a unique place in American history.”

While nearly killing himself for fame had not exactly been the plan for Evel Knievel, he was a smooth operator, and he deftly milked his hospital recovery for all it was worth. Even before Caesars, Taff says, Knievel had a knack for shrewd self-promotion. The only way he’d been able to arrange the Caesars Palace gig at all was through a series of bogus phone calls to the founder of the establishment, Jay Sarno. Posing as various journalists, Knievel would express a keen interest in covering “Evel Knievel’s upcoming jump at Caesars Palace,” creating a tremendous illusion of hype among the hotel leadership. Eventually, when Knievel approached them as himself, he was met with open arms.

In subsequent years, he continued on a campaign of daring jumps, his success mixed but the reaction of fans unwaveringly positive. The larger-than life quality of Knievel led to a couple Hollywood adaptations—one, Viva Knievel!, starring the stunt biker himself—and a highly profitable line of action figures. Wipeout or win, people across the country could not get enough of Evel Knievel. His endless self-endangerment for the sake of entertaining crowds had a distinctly American appeal to it.

So too did his stars-and-stripes style. As Taff recounts it, “It was an awful, dark period for American history. Evel comes along and says, ‘You know what? I’m going to change that. I’m going to bring patriotism back. I’m going to make patriotism cool.’” Rejecting the black leather badass aesthetic of groups like the Hells Angels, Knievel invariably favored colorful jumpsuits and flowing capes.

Taff certainly sees Knievel as a kind of superhero. “He was one of those people that was so magical,” he says. “He made dreams come true. He helped people.” Taff acknowledges, though, that the motorcycle maven had his hostile side too. Knievel trusted very few individuals in his life, Taff notes, and “had a reputation: if he didn’t like you, you better look out.” The low point in Knievel’s career was likely his assault of his former press agent Shelly Saltman in 1977, which surprised many and contradicted the wholesome portrayal of Knievel in the recently released Viva Knievel! As the story broke, the wacky feature film fizzled in international theaters.

Given Knievel’s tempestuous and solitary nature, Taff is especially grateful to have been able to call him a long-term friend. Taff was on hand for the recent unveiling of the Evel Knievel Museum in Topeka Kansas, which chronicles the thrill-seeker’s mercurial life in the limelight and boasts such staples of Americana as Knievel’s custom tractor trailer rig, “Big Red,” from which he made a number of characteristically dramatic entrances across his showboating career. Knievel himself has been dead ten years—what wound up killing him was pulmonary fibrosis—but his impact on this country is still readily appreciable, and his distinct daredevil persona resonates across the artifacts of the Topeka museum, as well as those of the Smithsonian.

Evel Knievel’s successes are worth celebrating, but what truly makes him memorable are all the occasions on which he failed, flagrantly, only to come back for more as soon as he had recuperated. This spirit of perseverance animated, and continues to animate, his far-flung fan base. “If I asked the average person, ‘Where was Evel’s biggest world record jump?’” says Taff, “they’d say ‘I don’t know.’ ‘When was it?’ ‘I don’t know.’ And then I’d say, ‘What was his biggest crash?’ And they’d say, ‘Oh, yeah! You mean Caesars Palace! Everybody saw that!’”

“He really was risking his life,” says Roger White, “and he proved it by getting banged up and almost killed—a few times.” The Smithsonian’s Evel Knievel memorabilia has not been on view for several years, but White says that is going to change in the near future, in large part due to the sustained interest of fans across the country. “There are plans to put the bike back on display,” he tells me. “Knievel’s legacy has legs.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)