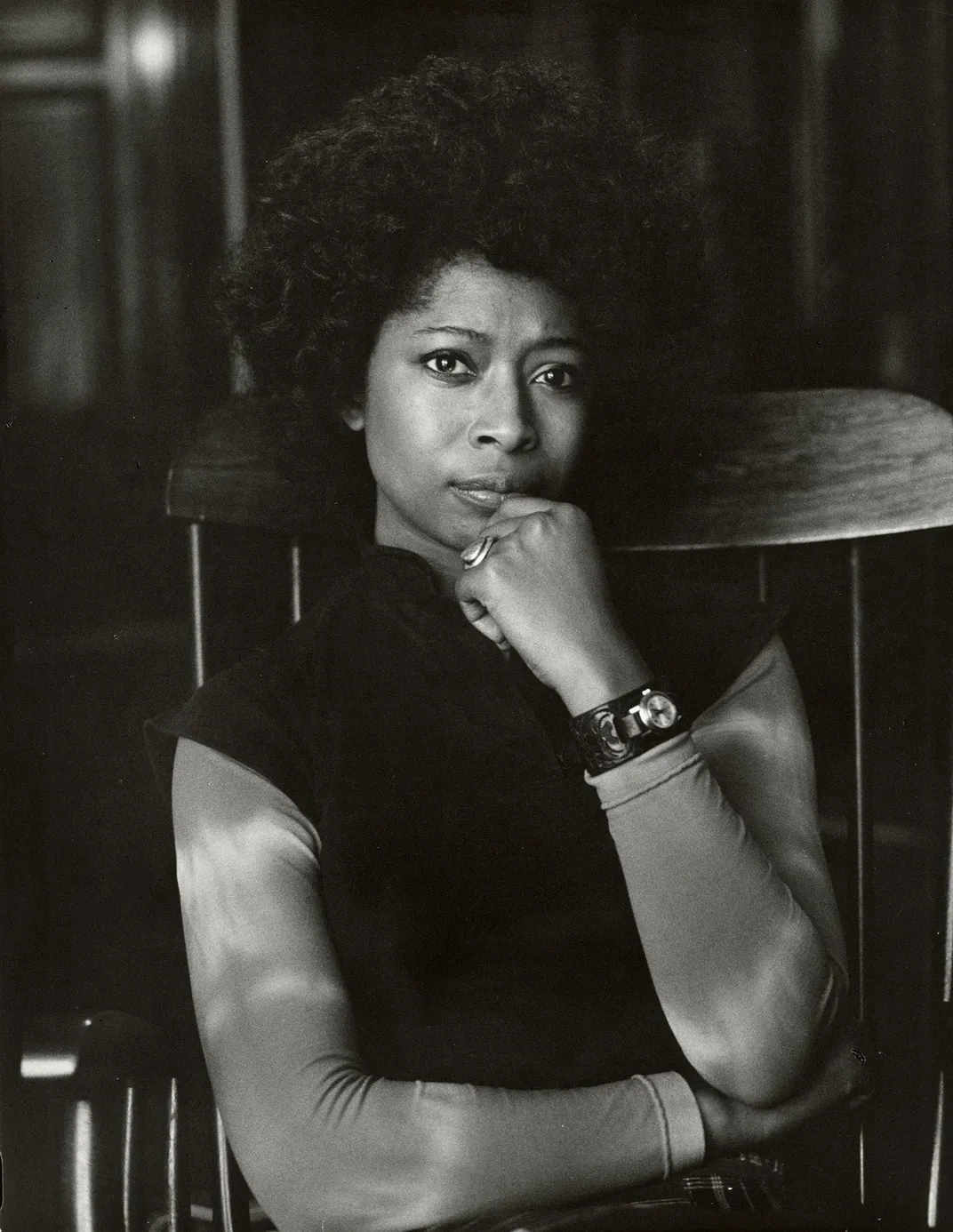

The month after A Raisin in the Sun opened on Broadway, photographer David Attie visited its author, 29-year-old Lorraine Hansberry, at her Greenwich Village apartment. On assignment for Vogue, he cataloged such details as ceiling-high bookshelves, a clunky typewriter and a vase filled with forsythia clippings, offering a sense of the space where the playwright had penned her searing exploration of racial segregation.

A photo of the author stands on the table next to a lamp and a stack of papers; a poster advertising the Sidney Poitier-led Broadway production is visible above a neighboring bookshelf. But the most striking aspect of the scene is an oversize, intimate portrait of Hansberry added in during editing. Captured during the same sitting, the superimposed image takes up an entire wall, dominating the composition and upping the number of Hansberry’s appearances in the tableaux to a total of three.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/c1/c4c106cf-72d9-4847-9b8d-9fb2e633a5fb/npg_93_92_hansberry_r.jpg)

As photography scholar Deborah Willis observed in 2008, the portrait exemplifies “this whole notion of [Hansberry’s] positive experience of living in an environment of self-pride. [It] became an affirmation of what she contributed to literature, to the stage.”

Hansberry, who drew on her personal experience of racism to become the first African American woman whose work was produced on Broadway, is one of 24 groundbreaking authors featured in the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery’s newest exhibition. Titled “Her Story: A Century of Women Writers,” the show spotlights such literary giants as Toni Morrison, Anne Sexton, Sandra Cisneros, Ayn Rand, Jhumpa Lahiri, Marianne Moore and Jean Kerr. Collectively, the museum notes in a statement, the women represented have won every major writing prize of the 20th century.

“This is a very highly decorated group,” says the museum’s senior historian, Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw. “And the objects in the exhibition are also very diverse. We have sculptures, paintings, drawings, a caricature and photographs. So it really provides the viewer with a strong cross section . . . of 100 years [of] women from many different backgrounds.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d6/e6/d6e66cc7-7905-4fc7-8a7d-c4e1579e986e/npg_2012_48_angelou.jpg)

According to Shaw, Hansberry is one of the most radical women included in the exhibition. An ardent supporter of the American Communist Party, the author also advocated for aggressive anti-racist action at a time when segregation was the norm. In May 1959, she told journalist Mike Wallace that black Americans had “a great deal to be angry about,” adding, “I feel, as our African friends do, that we need to point toward the total liberation of the African peoples all over the world.”

Born in Chicago in 1930, Hansberry grew up on the city’s segregated south side. But in 1937, her parents opted to move the family to the all-white neighborhood of Woodlawn, defying Chicago’s racially charged housing covenants and, in doing so, attracted the ire of violent white mobs. On one occasion, a brick thrown through the window almost struck Hansberry in the head; years later, she recalled her mother “patrolling [the] house all night with a loaded German luger.”

Tensions soon rose enough to convince Hansberry’s father, Carl, to bring the case to the courts. In 1940, the Supreme Court ruled in his favor, reaffirming the family’s right to live in Woodlawn and paving the way for the eventual dismantling of restrictive housing covenants. Carl himself died unexpectedly six years later, succumbing to a cerebral hemorrhage while scouting out new homes for the family in Mexico City. Hansberry later suggested that “American racism helped kill him.”

These experiences closely informed the plot of A Raisin in the Sun, which follows a black family’s struggle to better its prospects following the death of its patriarch. After much debate over how to spend a $10,000 life insurance check, the Youngers agree to put the money toward the down payment for a house in an all-white neighborhood.

Hansberry’s play succeeded against all odds, winning her the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award, earning four Tony Award nominations and spawning a Golden Globe-nominated 1961 film of the same name.

Today, says Shaw, Raisin continues to resonate—particularly at a time “when one of the political talking points has been about ‘saving the suburbs’ from low-income development, which is another way of instituting modern-day redlining to keep neighborhoods economically segregated and also, to a certain extent, racially segregated.”

Hansberry died of pancreatic cancer on January 12, 1965. Just 34 years old, she left behind an extensive oeuvre, including a second Broadway play centered on the decidedly different subject of Greenwich Village’s Bohemian culture; several unpublished screenplays emblematic of her radical philosophies; and an array of diaries, letters and papers documenting such topics as her closeted lesbian relationships.

Before her death, the ailing author questioned her dedication to activism, penning a journal entry that asked, “Do I remain a revolutionary? Intellectually—without a doubt. But am I prepared to give my body to the struggle or even my comforts?”

She concluded, “Comfort has come to be its own corruption.”

Much like Hansberry, Sandra Cisneros draws inspiration from her childhood in Chicago. The collection of vignettes in her 1984 The House on Mango Street traces a year in the life of the young Chicana woman Esperanza Cordero; deftly conveying its protagonist’s evolving relationship with her community, the text also chronicles issues of race, class and gender.

“One day I’ll own my own house,” she reflects in the book, “but I won’t forget who I am or where I came from.”

Cisneros—whose accolades include an American Book Award, the National Medal of Arts and a MacArthur “Genius Grant”—initially approached House on Mango Street as a memoir, intending to write “something that was just mine, that no one could tell me was wrong.” But the project evolved after she began working at a high school in a Latino neighborhood of Chicago.

“I started writing stories of my students’ lives and weaving it into this neighborhood from my past,” the author said in 2016. “. . . I feel as a writer that I have a gift of expressing things that people feel, and speaking for them, and also creating clarity and bridges between communities that misunderstand one another.”

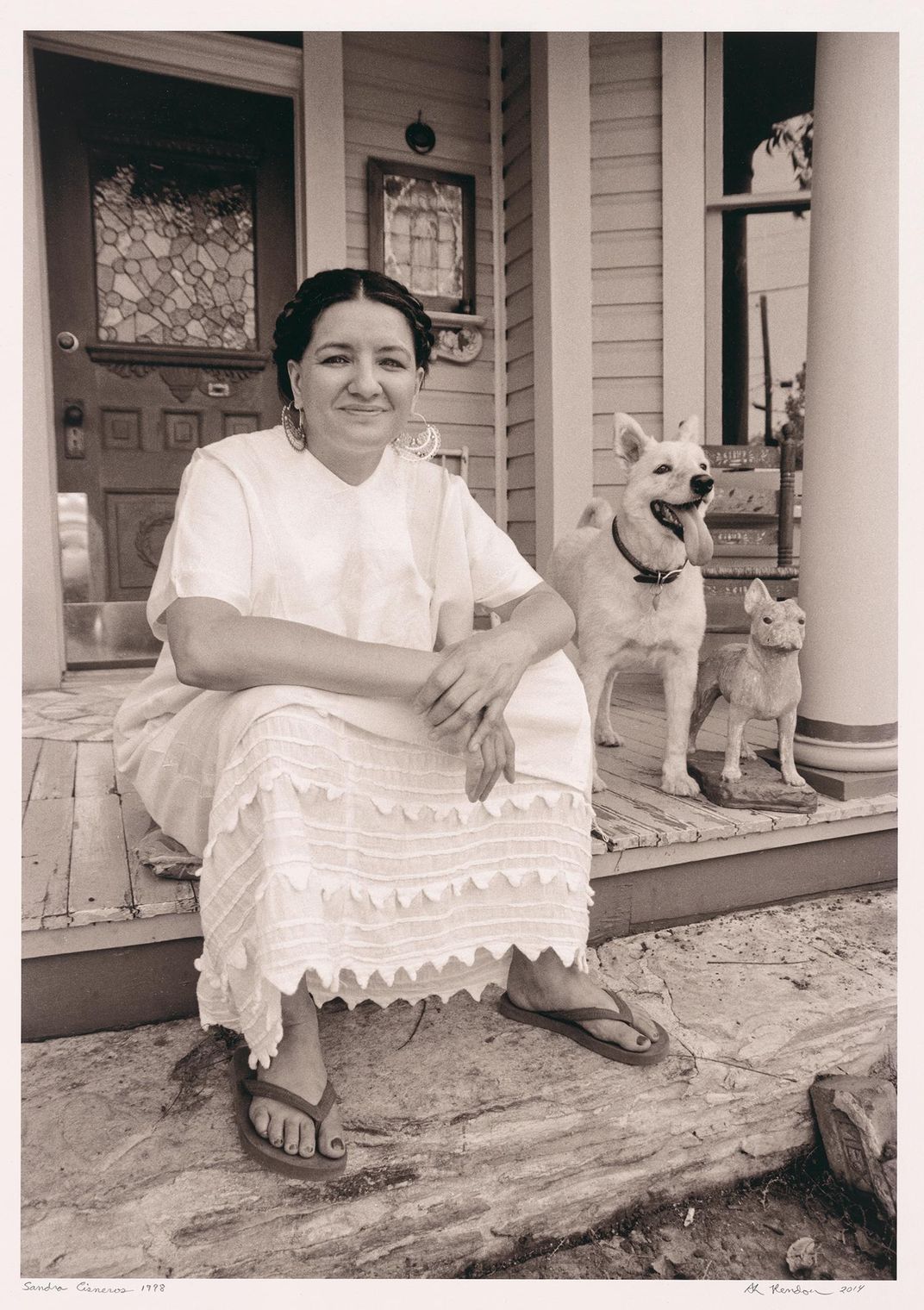

The exhibition features a portrait of Cisneros sitting on the front porch of her San Antonio home with her pet dog. Taken in 1998 by Al Rendon, who is known for his photographs of local Hispanic leaders, the image shows its subject sporting traditional Mexican dress (minus a pair of flip flops accentuated by brightly colored toenail polish). She wears large hoop earrings, and her hair, carefully parted in the middle, is arranged in a braided updo.

“The immediate response is that she looks like the artist Frida Kahlo,” says Shaw. “That's an association that's easy to make visually, [but] it's less about her emulating Kahlo than it is about a common respect for, and love of, Mexican folk heritage and the aesthetic . . . of the 1940s and '50s.”

Rendon’s portrait offers an intimate view of Cisneros, seemingly placing the viewer in direct conversation with the writer. “I love the way she’s sitting on the steps, as though she's talking to a neighbor,” Shaw adds. “It has a very casual, relaxed feeling.”

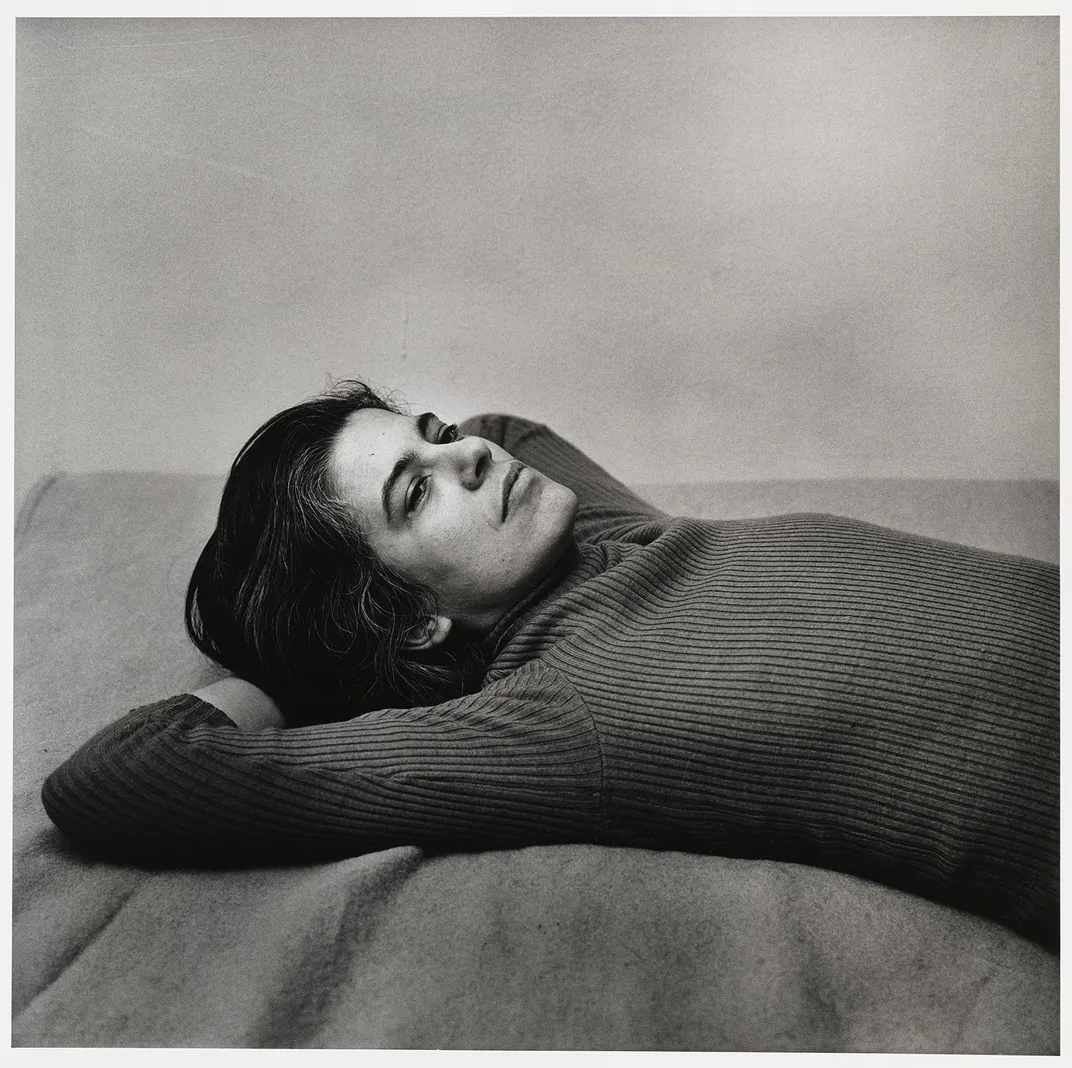

Compared with the easy familiarity of Hansberry’s and Cisneros’ portraits, the exhibition’s 1989 photograph of Maxine Hong Kingston is almost unsettling. Peering out at the viewer with a contemplative expression, the writer takes up just a small section of the composition. Everything else in the room, from a framed painting to a window and an out-of-place tree with a bird’s nest in its branches, is blurred and bathed in overexposed light.

“When we see her in this room, we get a kind of odd indoor-outdoor feeling,” Shaw explains. “. . . She’s down off to one side, and there is this whole larger space of imagination that opens up on the left.”

Anthony Barboza’s seemingly discordant snapshot echoes the feelings of liminality evident in Kingston’s writing. Born to Chinese immigrants in 1940, she grew up on folklore and family histories, always cognizant of her status as an unwitting outsider caught between the worlds of Chinese and American culture.

As a teenager, Kingston read Louisa May Alcott’s novel Eight Cousins and found herself identifying not with the white female protagonist, but an exaggerated, exoticized Chinese character named Fun See.

“I felt like I was popped out of her writing,” the author recalled in a recent interview with the New Yorker. “Out of American literature.”

Kingston’s debut book, The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts (1976), sought to reclaim her immigrant identity, blending fiction and nonfiction in “a new kind of autobiography” based on the “dreams and fantasies of real people,” as she told the Guardian in 2003.

Centered on real and mythical women alike, the book combines anecdotes from Kingston’s own life with stories shared by her mother and other female relatives whose accounts blur the boundaries between truth and invention. Four years after The Woman Warrior’s publication, the writer released China Men, a similarly genre-defying collection inspired by her male family members.

In 2003, Kingston was arrested after participating in an anti-war protest on International Women’s Day. She ended up sharing a jail cell with fellow featured writer Alice Walker—an experience detailed in the former’s 2012 verse memoir, I Love a Broad Margin to My Life.

This unexpected connection speaks to the “bonds and relationships” forged by a number of the women included in “Her Story,” says Shaw. Walker, who is perhaps best known for her 1982 epistolary novel, The Color Purple, wrote about what it was like to be a poor black woman in the American South. According to the curator: “That really resonates in a lot of the ways with what Kingston was writing about being first generation, living in a community that is tied to a past, [and] trying to reconcile where one stands in a world that is all about assimilation into a kind of Americanness that can be at odds with the traditions, values and expectations of one’s family.”

Kingston, for her part, aptly summarized an obstacle faced by writers of color who choose to focus their work on marginalized communities. Speaking with the Guardian in 2003, she declared, “I resented critics who reviewed my work as Chinese literature when I felt I was writing American stories about America.”

Some of the 24 women spotlighted in the exhibition were better known during their lifetimes than they are today. In the 1950s and ’60s, for example, Jean Kerr won admirers for her comedic takes on white, middle-class suburbia, which “spoke to a very specific moment . . . [and have] become dated in certain ways,” Shaw says. But others’ writings continue to hold broad appeal long after their creators’ deaths: Originally published in 1911, Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden was first made into a film in 1919. One hundred and one years later, the coming-of-age story is still being adapted for the silver screen.

Among the most striking portraits included in her “Her Story” is a 1998 picture of Toni Morrison that appeared on the cover of Time magazine. “Here’s this beaming, middle-aged black woman with her gray hair on full display. It rhymes with this Mongolian fur collar that is also black and white, salt and pepper,” Shaw says. “She’s got . . . these beautiful dreadlocks that have been pulled back from her face and this big smile on her face.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b5/5a/b55ad38a-65cc-43fc-a19c-8bf114035d4b/npg_2019_141.jpg)

Comparatively, Robert McCurdy’s 2006 painting of the Beloved author (on view in the museum’s “20th-Century Americans: 2000 to Present” gallery) depicts an unsmiling woman with her hands tucked into the pockets of a gray sweater. “I love the contrast of these two portraits, and it’s great to have them up at the same time because it really shows the sitters have different expressions and attitudes,” the curator explains.

She adds, “The Time cover makes Morrison look like a really friendly person you want to go and hang out with, and then the McCurdy portrait makes her look so formidable and very challenging.”

From Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon (1947) to Dorothy Parker’s “sarcastic poetry,” Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s screenplays, Susan Sontag’s literary criticism, Joyce Carol Oates’ multi-genre fiction and Maya Angelou’s autobiographical novels, “there is sure to be an author here [who] is on everyone’s list of favorites,” Shaw concludes.

“Her Story: A Century of Women Writers” is on view at the National Portrait Gallery through January 18, 2021. Free, timed-entry tickets are required for access to the museum.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c2/16/c21664c0-ca9c-43ec-81f7-291ac346a941/npg_89_88_parker.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/90/6990485b-df73-4648-bd68-02a79de63ea9/npg_2004_42_brown.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/a8/74a806c7-b6e4-4b9d-adf9-40a15082924f/mobile_marilynne.jpg)

:focal(582x188:583x189)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/a5/81a559e7-ade4-456f-8dee-29210a3876c1/social_marilynne.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)