World War I Letters From Generals to Doughboys Voice the Sorrow of Fighting a War

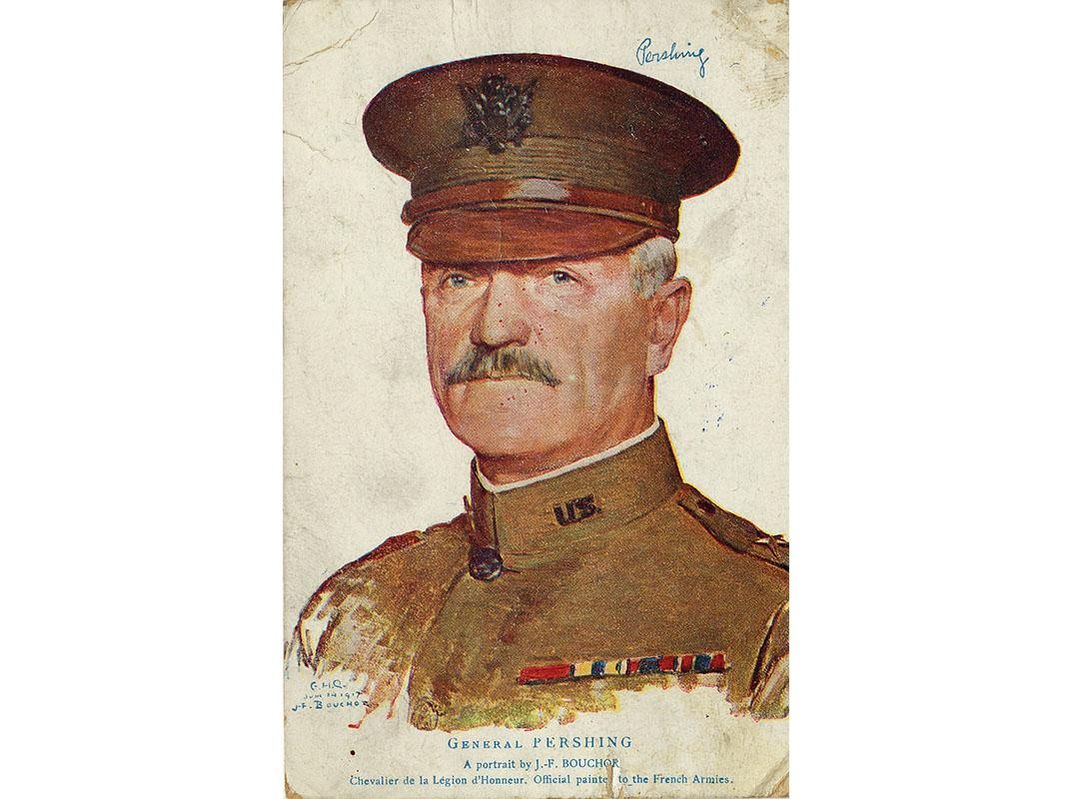

An exhibition at the National Postal Museum displays a rare letter from General John Pershing

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/cc/45cc7729-8003-4941-a0a5-abf98aa8c292/165ww262a132naraweb.jpg)

One of several exhibitions in the nation's capital noting the 100th anniversary of America’s involvement in World War I begins and ends with letters by Gen. John J. Pershing.

One of them, of course, is the widely distributed missive to “My Fellow Soldiers,” after which the exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C. was named, extolling the troops’ extraordinary work.

“Whether keeping lonely vigil in the trenches or gallantly storming the enemy’s stronghold; whether enduring monotonous drudgery at the rear, or sustaining the fighting line at the front, each has bravely and efficiently played his part,” Pershing wrote.

While every member of the American Expeditionary Forces under his command received that communication, a different, quite personal handwritten letter, opens the show. In it, Pershing shares the personal grief to a family friend at the horror of losing his wife and three young daughters in a house fire two months earlier, while he was deployed in Fort Bliss, Texas.

October 5, 1915.

Dear Ann: -

I have been trying to write you a word for some time but find it quite impossible to do so.

I shall never be relieved of the poignancy of grief at the terrible loss of Darling Frankie and the babies. It is too overwhelming! I really do not understand how I have lived through it all thus far. I cannot think they are gone. It is too cruel to believe. Frankie was so much to those whom she loved, and you were her best friend.

Ann Dear, if there is anything I can do for you ever, at any time, please for Frank’s sake let me know. And, I want to hear from you just as she would want to hear from you. [page break] My sister and Warren are here with me. Warren is in school. I think his is such a sad case – to lose such a mother and such sisters.

I am trying to work and keep from thinking; but oh! The desolation of life: the emptiness of it all; after such fullness as I have had. There can be no consolation.

Affectionately yours

John J Pershing

It’s the first time the letter has been on public display, says Lynn Heidelbaugh, the postal museum curator who organized the show. “This is a touching letter of the heart wrenching, about how he’s dealing with his profound grief.”

Just a year and a half after that tragedy Pershing was made commander of the American Expeditionary Force by President Woodrow Wilson, overseeing a force that would grow to two million soldiers.

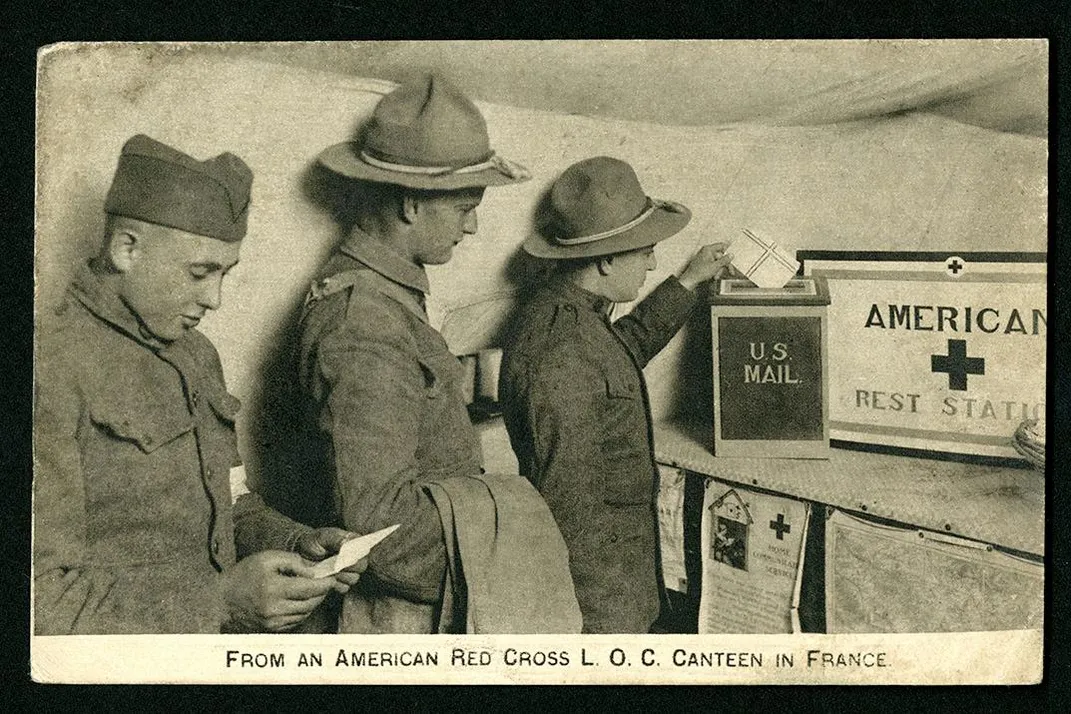

If World War I was unlike any conflict fought before, that was also reflected in the post office, which had to handle an unprecedented number of cards, letters and packages overseas Before cell phones, Skype and email, pen and paper was the only way for soldiers to stay in touch with loved ones and the postal service struggled to keep up.

“In that first year alone, there were 52 million pieces of mail going back and forth, most of it from the U.S., but a fair number coming from the military as well,” Heidelbaugh says. “We wanted to show how quotidian letter-writing was. This is what you did as much as we email today."

“My Fellow Soldiers: Letters from World War I” is the first temporary exhibition within the permanent “Mail Call” corner of the Postal Museum covering mail from all the U.S. armed conflicts. Many of the items are donated from the Center for American War Letters at Chapman University in Orange, Calif. But in all, more than 20 institutions lent pieces for the show.

Because of the fragility of paper; the display will change over time, with other letters and other stories swapped in, as others are removed, Heidelbaugh says. But all of its items will be available for examination—and transcribed—in a nearby electronic kiosk.

“There are a lot of stories to cover,” she says. “We do cover the military mail of soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines, but we also have letters from people working for social welfare organizations overseas—some of the people who were there even before the U.S. entered the war,” she says. “And then we have people that are working in the Red Cross campaign as well as on the home front. We really wanted to get as many voices and perspectives as we could.”

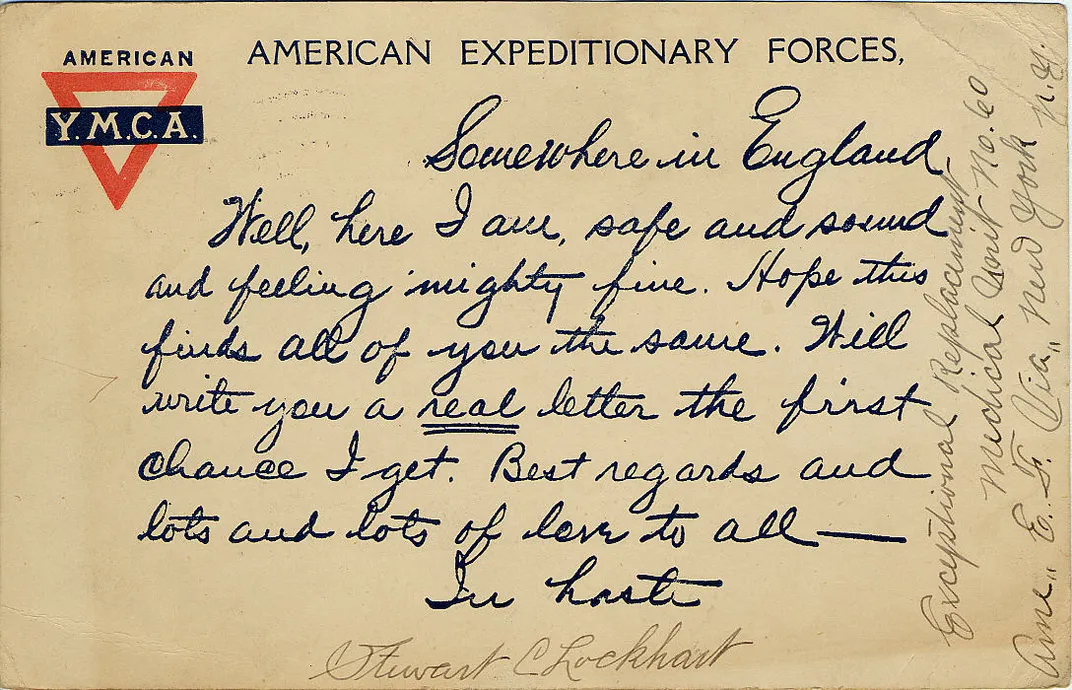

Many are handwritten and “their personality comes out through their handwriting and turn of phrase.” Others are typewritten as an efficient way to get a lot of words on a page.

But there was always a question of how much the writers could express, since they could fall in enemy hands or were otherwise examined by military censors to ensure secrets or locations were not revealed.

“‘Somewhere in France’ becomes a huge phrase,” Heidelbaugh says.

Letters give an insight on women’s involvement in the war effort and African-American troops whose participation in segregated units was more welcomed than their citizenship was at home.

The letters on hand may reflect the gulf between the educated and non-literate, Heidelbaugh adds, but there are some examples that suggest letters had been dictated to others.

One World War I veteran writes his perspective on foreign war to his son, about to embark on combat in World War II.

“It’s not a letter about bravado, Heidelbaugh says. It says, ‘You will have adventures, but it’s the people that you meet and your own character that will get you through.’ It’s a touching letter and it in many ways reflects Pershing’s letter about the character of the military, to face the trials of war.”

And because the exhibition will change, replacing and adding frail letters over its 20 months, repeat visits will be rewarded.

In addition to the letters, there are artifacts of the era, such as examples of pens designed to work in the trench, or some of the many examples of sheet music about the process of writing to the troops over there. One from 1918 is titled “Three Wonderful Letters from Home.”

World War I is when the Army Post Office was established—the APO—as a way to get mail to a specific unit without naming its location. The APO is still in existence 100 years later.

Though modern electronic communications provides more instant contact with loved ones back home, Heidelbaugh says the personal letter still has a place. “Through my interviews and taking to people, even studies show that a personal letter on paper has carried more weight—providing that tactile experience in that connection.”

Through correspondence official and personal, Heidelbaugh says “we hope this will inspire people to go back to their own family collections, if not to their WWI letters, then other sets of letters, or to consider their own communication.

“How do they even archive communication today or create records of our communication, how we express ourselves? These are analog and relatively easy to save and people share their stories that they might not have been able to have come home and shared themselves. And now with 100 years of perspective we can share those stories.”

“My Fellow Soldiers: Letters from World War I” is on view through Nov. 29, 2018 at the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum Mail Call Gallery. Read an excerpt from the new book My Fellow Soldiers by Andrew Carroll, a companion to the exhibition, on the death of President Theodore Roosevelt's son Quentin.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)