World’s Largest Stamp Gallery to Open in Washington, D.C.

America’s most famous stamp, the Inverted Jenny, goes on permanent view for the first time in history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130919113040postage-stamp-470.png)

Stamp collectors like nothing better than a mistake. Take for example the notorious blunder of 1918 that flipped a Curtiss Jenny aircraft upside-down on a United States 24-cent postage stamp. The so-called “Inverted Jenny” has since become America’s most famous stamp and one of the world’s most famous errors. “This is a stamp that just makes every collector’s heart beat,” says Postal Museum curator Cheryl Ganz.

On Sunday, September 22, the original Inverted Jenny goes on permanent view for the first time in Smithsonian history. Presented in a four-stamp block with three singles, the Jennies are the crown jewels of the new William H. Gross Stamp Gallery, a 12,000-square-foot addition to the Postal Museum. The gallery will feature some 20,000 philatelic objects, a handful of which are reproduced below. Curator Daniel Piazza hopes that the Jennies will become a “stop on the tour of Washington,” canonized with other great artifacts in American history.

The Jenny was the first U.S. airmail stamp as well as the first airmail stamp to be printed in two colors. Its complex production process allowed ample room for error. One collector, William T. Robey, anticipating a potentially lucrative printing error, was waiting for the new stamps at a Washington, D.C. post office on May 14, 1918. He asked the clerk if any of the new stamps had come in. “He brought forth a full sheet,” Robey recalled in 1938, “and my heart stood still.” The image was upside down! “It was a thrill that comes once in a lifetime.”

Robey sold the sheet of 100 stamps for $15,000. That sheet, which was later broken up, has a storied history that includes resale, theft, recovery, deterioration and even some fleeting disappearances. The National Postal Museum says that the Inverted Jenny is the stamp that visitors most often ask for, but because of conservation issues, the stamps were rarely put on view; the last time was in 2009.

The Jennies will be displayed in a custom-designed case fitted with lights that automatically switch on and off as visitors move through the exhibit. Also debuting on the Stamp Gallery’s opening day is a new $2 USPS reprint of the Inverted Jenny, so visitors can take home the best loved error in philatelic history—at a fraction of the price tag.

UPDATE 9/23/2013: This post has been updated to indicate that the Jenny stamp was the first bicolored airmail stamp and not the first bicolored stamp.

Scroll down to preview other treasures from the William H. Gross Stamp Gallery:

John Starr March’s pocket watch, 1912 This watch probably stopped when RMS Titanic sank in the Atlantic. Recovery ship crew members found it on the body of John Starr March, an American Sea Post clerk.

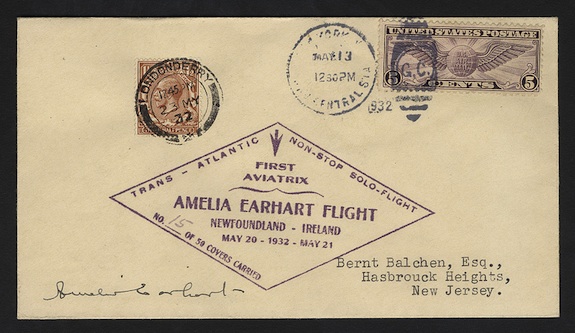

Amelia Earhart solo transatlantic flight cover, May 20, 1932 On her historic solo flight across the Atlantic, Earhart carried 50 pieces of unofficial mail—each postmarked before and after landing, cacheted, numbered and autographed to document the record-setting event.

Amelia Earhart’s flight suit, 1920s Amelia Earhart wore this brown leather flight suit designed for female pilots. Fully lined with orange, red and brown plaid flannel, it provided insulation from the elements while flying in an open cockpit or at high, chilly altitudes. The snap collar protected against drafts.

Pilot Eddie Gardner’s aviation goggles, 1921 One of the first pilots hired by the Post Office Department, Eddie Gardner set a record by flying from Chicago to New York in a single day (September 10, 1918). He was wearing these borrowed goggles when his airplane crashed during an aviation tournament in 1921. He died from injuries.

Hindenburg disaster card, May 6, 1937 Under this panel is a piece of mail salvaged from the wreckage of the airship Hindenburg. The burnt card reached its address in a glassine envelope with an official seal. At least 360 of the more than 17,000 pieces of mail on board the airship survived the disastrous fire.

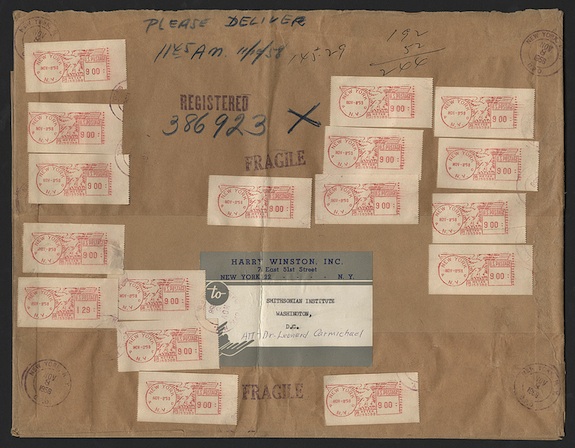

Hope Diamond wrapper, November 8, 1958 Jeweler Harry Winston mailed the world-famous Hope Diamond to the Smithsonian Institution in this wrapper, registered first class mail. It traveled by Railway Mail Service from New York to Union Station. The total cost was $145.29, of which $2.44 was postage. The remainder covered the expense of the one million dollar postal insurance.

Street collection box damaged September 11, 2001 Located at 90 Church Street, across the street from the World Trade Center, this mailbox was scratched, dented and filled with dust—but its body and the mail inside remained intact.

San Francisco earthquake cover, April 24, 1906 Postmarked six days after the devastating 1906 earthquake, this cover arrived in Washington, D.C., on April 30 with 4 cents postage due. Makeshift post offices in San Francisco accepted mail without postage and sent it to the receiving post office, where postage due was assessed and collected from the recipient.

Silk Road Letter, 1390 This is the oldest paper letter in the National Philatelic Collection. Mailed by a Venetian merchant in Damascus on November 24, 1390, the text discusses the prices for luxury fabrics and spices, like cinnamon and pepper. It was carried by courier to Beirut, where it boarded a Venetian galley, and arrived in Venice on December 26, having traveled 1,650 miles in one month.

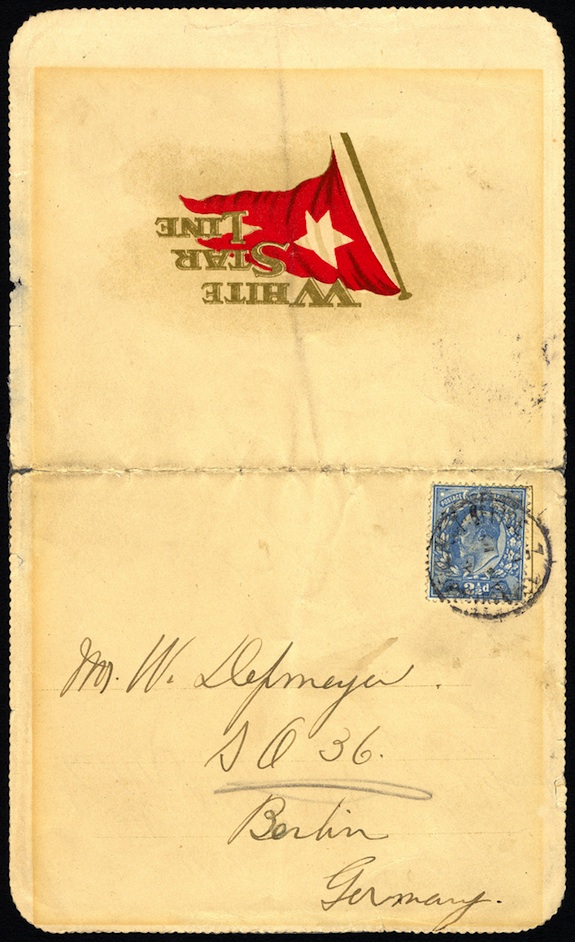

Letter mailed aboard RMS Titanic, April 10, 1912 First-class Titanic passenger George E. Graham, a Canadian returning from a European buying trip for Eaton’s department store, addressed this folded letter on ship’s stationery. Destined for Berlin, it received Titanic’s onboard postmark (“Transatlantic Post Office 7”) and was sent ashore with the mail, probably at Cherbourg, France. Mail is one of the rarest artifacts from Titanic.