“Worlds Within Worlds” at the Sackler Tells Stories Within Stories

A new exhibit explores the prosperous rule of the Mughal empire and the cross-cultural art it inspired

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/37/333787ef-d52a-4fc0-8146-98cfa2b8eb5a/s1986141-2.jpg)

As Akbar, one of the greatest Mughal emperors and patron of the arts, once said, “There are many that hate painting; but such men I dislike.”

Curator Debra Diamond would tend to agree. She is a driving force in gathering together the lavish Mughal paintings on display in the new exhibition, “Worlds Within Worlds: Imperial Paintings from India and Iran” that opened July 28 at the Sackler Gallery of Art. The exhibition features intricate paintings rich with color from the Mughal empire, dating from 1556 to 1657, and commissioned by the three greatest art patrons of the era—the emperors Akbar (1542-1605), Jahangir (1569-1627), and Shah Jahan (1592-1666). The Mughal empire extended across India and Persia, today’s Iran, and was led by Muslim rulers descended from Genghis Khan. Their rule linked Persia with India’s Hindu Rajput kingdoms.

“We wanted to show something fabulous and the interconnections between worlds,” Diamond states. The exhibition is among a number of events and shows this year to mark the Sackler Gallery’s 25th anniversary, and is the first to highlight the museum’s Persian art collection.

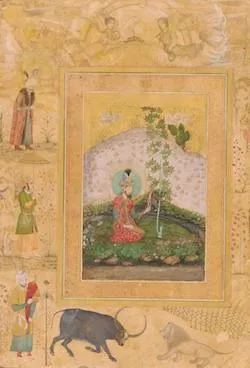

To showcase their power, influence and wealth, emperors from the 1500s hired painters and writers to make lavish books, known as folios. The works took years to complete and could consume every hour of the artists’ life and served to define the ruler’s legacy as world leaders. The exhibit brings together 50 such works.

Each emperor had a unique aesthetic. Diamond points to the “dynamism” of Akbar, the “refinement” of Jahangir and the “opulent formality” of Shah Jahan.

Shah Jahan, whose name in Persian signifies “King of the World,” ruled from 1628 to 1658. Famously known for commissioning the Taj Mahal, his portraits depict him as the very embodiment of wealth and power, with border imagery laced in exquisite goldleaf detail. As with his most famous building project, Jahan looked to the finest of details to convey his message. He wrote, “beautiful things. . . create esteem for the ruler in the eyes of and augments dignity.”

Powerful and wealthy as the ruler proclaimed, in the folio entitled, Late Shah Jahan Album, a sad story emerges. There, Jahan’s son, Shah Shuja is depicted (left). Shah Shuja, a boy of just two or three years, is seen on a single page of the folio looking away from the viewer. Diamond discovered that the boy had contracted a serious disease and was gravely ill. “The family unit prayed to God to save him,” she says. “In the portrait he is a sweet and loving baby and exquisitely painted.”

Jahan’s artists used an unusual technique of tightly piecing together cut and fitted, highly polished colored stones, otherwise known as pietra dura, in a gorgeous mosaic. Radiant borders specked with gold leaf reflect Jahan’s love for jewels, gems and flowers.

Emperors prided themselves not just on their own artistic legacy, but also on their mastery of the art history of the period. Shah Jahan’s predecessor Jahangir, who ruled from 1605 to 1628 said, “No work of past or present masters can be shown to be that I do not instantly recognize who did it.” In his portraits, Jahangir was depicted “taller and more slender” than previous emperors, Diamond says, in a display of arrogance and prestige. “He sees himself as a cosmopolitan ruler,” she says, and not just a fearfully strong leader, an important distinction for someone presiding over a culturally heterogeneous territory.

In conjunction with the opening of the exhibit, the film series “Indian Visions at the Freer” begins this month and features the Alms of a Blind Horse on July 14 and the Mughal-e-Azam on August 11. For family entertainment, “Inspired by India: A Family Celebration” on Saturday, August 11, celebrates Indian subcontinent cultures. The exhibition will be on view through September 17, 2012.