WWII Navy Corpsman Collected Birds Between Pacific Theater Battles

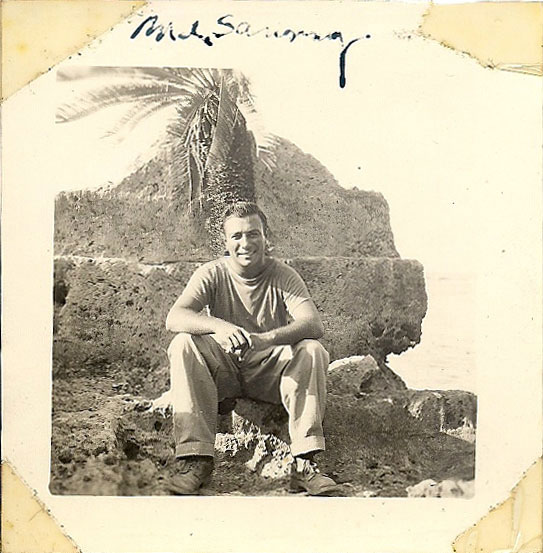

Sammy Ray was a bird zoologist when he enlisted in the Navy and was recruited by Smithsonian to collect exotic specimens in the South Pacific. Photo courtesy of Sammy Ray.

“The carnage on the beach was unbelievable,” said Sammy Ray, recalling when he landed on the island of Peleliu with the 1st Marine Division in September 1944. “Still to this day, I don’t know how I got out alive,” Ray says.

As the Navy senior hospital corpsman for the division, Ray experienced firsthand the horrors of the casualties as his medical team attempted to save lives and limbs. Those traumatic memories were still vividly fresh in his mind several months later on April 1, 1945, when his unit landed on the beaches of Okinawa. Ray was filled with sharp anxiety, fearing the loss of life on Peleliu foreshadowed what laid ahead for his unit on Okinawa.

His fears were, fortunately, unfounded; their invasion of the island was uncontested by the Japanese. Nonetheless, on April 1, 2011, 66 years to the day after landing on Okinawa, an emotional Sammy Ray visited the Smithsonian collections to view many of the 171 bird specimens he had collected, preserved and shipped to D.C. from various South Pacific islands during World War II.

“To see the birds again, and the fact it happened on the anniversary of a day that was very strongly etched in my mind…it took me back to what I was experiencing that day .”

His contributions during World War II, along with the efforts of many other scientists and servicemen who worked in the South Pacific, helped the Smithsonian gather a wide-ranging collection of biological specimens from the relatively unexplored ecosystem.

A special exhibit opening July 14 in the Museum of Natural History will explore Smithsonian’s collecting efforts during World War II through photos, specimens, correspondence and museum records that have been maintained and studied by specialists at the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

“When Time and Duty Permit: Collecting During World War II” exhibits many pieces of Ray’s story firsthand, including a pristinely preserved bird skin he stuffed and letters he exchanged with Alexander Wetmore, who was an ornithologist and Secretary of the Smithsonian at the time. In one such letter, Ray said that as dedicated as he was to collecting birds, he was committed to the responsibilities he had as the senior hospital corpsmen. He penned to Wetmore he would collect bird specimens “when time and duty permit.”

Ray, a bird zoologist with a college degree at the time he enlisted in the Navy, was recruited by Wetmore to be a specimen collector before he had even received his station assignments.“From that moment on, preparations were made for me to collect in the South Pacific,” Ray said. “No one knew for sure but that was the guess.”

Wetmore’s gamble paid off; Ray was assigned to meet the 1st Marine Division in New Caledonia, about 100 miles north of Australia. From there, his division hopped from island to island, which put Ray in a perfect position to collect a variety of exotic birds.

“I was the most-armed non-combatant to ever hit the beach in the South Pacific,” Ray quipped. In addition to his military-issued weaponry and a heavy arsenal of medical equipment, the Smithsonian provided him with a special collecting gun. The gun was retrofitted with an auxiliary barrel for discharging “dust shot” — light ammunition designed to kill small birds without destroying their bodies.

Ray prided himself on his ability to bring bird pelts “back to life”. He collected this buttonquail on Okinawa. Photo courtesy of Smithsonian Archives.

After hunting down a bird, Ray would remove its skin and use wood straw or hemp to stuff the inside of the pelt, sewing the skin back together to create an real “stuffed animal” of sorts. Ray’s impeccable taxidermy skills have stood the test of time, nearly 67 years later his specimens are still immaculately well-preserved.

But his efforts weren’t always appreciated or understood by other members of his unit.

Ray recalled a time when he spent the night in a mangrove swamp after staying out late to collect birds. A fitful night was spent with iguanas crawling across his body before the morning sun rose. When he returned to camp, a line of men standing was around their colonel at 6 a.m.. Ray knew immediately that they had been looking for him.

Although his bird collecting at first landed him in trouble with the unit’s colonel, Ray used his ingénue to establish a working relationship with the commander. The colonel warmed to Ray as soon as he learned that he was the senior hospital corpsmen. In such a position, Ray had access to the medical supply of alcohol, a hot commodity among military men. By satiating the colonel’s thirst for alcohol, Ray was able to carry on his bird collecting without interference.

Upon completing his tour of duty in November 1945, Ray continued in his studies of biology to earn his master’s and Ph.D degrees from Rice University through a fellowship program sponsored by Gulf Oil, concentrating on understanding parasite life cycles. Ray, now 93 years old, teaches biology at Texas A&M University Galveston, where he has been an influential faculty member, mentor and teacher since 1957 as a highly respected shellfish expert and self-titled “oyster doctor”.

“When Time and Duty Permit: Collecting During World War II” is located on the ground floor of the Constitution Avenue lobby at the Museum of Natural History and will run from July 14, 2012, through late May 2013.