Yikes! The Sky is Falling. And a Meteoric Dispute Ensues

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/linda2.jpg)

Around this time each year, geologists from the department of mineral sciences at the National Museum of Natural History anxiously await the arrival of hundreds of meteorites that are collected annually from Antarctica. The space rocks are sent thousands of miles first by ship, and then by truck to the museum on the National Mall.

What the geologists weren’t expecting when the shipment of 1,010 meteorites arrived last week was that a meteorite would crash down practically in their own backyard. It slammed through the roof of a doctor’s office in Lorton, VA, just a half hour’s drive away.

“It was good timing, we were lucky—or, I guess, that meteorite is lucky it came at the right time,” said Carri Corrigan, a geologist at the museum, who was already at work analyzing this year's meteorite harvest.

Though thousands of metric tons of space rock reach our planet each year, much of it burns completely as it passes through the earth’s atmosphere. The rocks that do make it are more likely to land in the sea or in desolate terrain (Antarctica is a great place to find them because the dark rocks are visible on the ice) than they are to land in populated areas. In fact, you’re more likely to be struck by lightning than you are to be hit by a meteorite—the only recorded instance of human impact was in Sylacauga, Alabama in 1954, when Elaine Hodges was struck by a meteorite in the hip while napping on her couch. (She survived but, Ouch!)

Corrigan says she can think of only two meteorites (aside from the one recovered in Lorton) that fell and were then recovered in the past year: one in West, Texas; the other near St. Catharines in Ontario. To have one so close, at a time when analysis was already underway, was "truly special," Corrigan said.

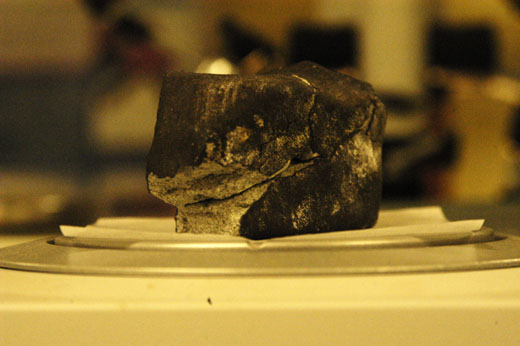

It also meant that I had a chance to visit the U.S. National Meteorite Collection (run by the museum) as analysis got underway. I was one of the few people able to see and hold the fist-sized meteorite—ash gray with sparkling pieces of metal and a burned charcoal-gray fusion crust.

Of course, I didn’t know at the time that, as Corrigan explained, the dark exterior of the meteorite was actually a fusion crust, left by the residue of melted rock as it flew through the atmosphere, or that the sparkles that caught my eye under the microscope were actually metal.

But then again, I also didn’t expect the “Lorton meteorite” to be so small—between one-half and three-quarters of a pound—compared to the big, hurling balls of green fire I associated with meteorites, thanks to the science fiction movies I watched as a child.

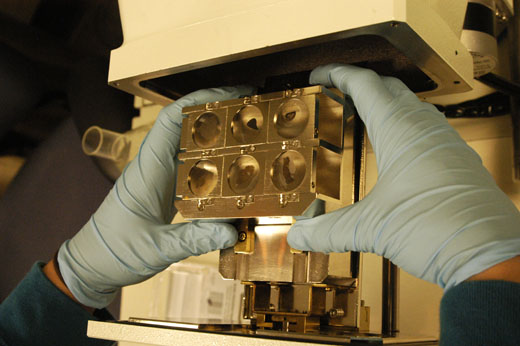

We had to use a sample much smaller than that—a chip that fit neatly in the center of a one-inch glass slide—and place it into a table-sized electron microprobe, which streamed 20 nanoamps of current through the sample and allowed us to take a closer look. It’s similar to the way other gems and minerals in the museum’s collection, like the famous Hope Diamond, and lava and salt rocks from Hawaii, are analyzed, Corrigan said.

When the Lorton sample came under the probe, what appeared on the trio of screens beside it looked almost like a density map, with misshapen ovals and circles in differing shades of gray and black, and occasionally, a brassy yellow.

The researchers told me the look is typical of an ordinary chondrite, the kind of meteorite Corrigan and others suspect the "Lorton Meteorite" to be, and the kind of meteorite that comprises the majority of the museum’s collection. Ordinary chondrites, and other types of chondrites, come from the asteroid belt.

The brassy yellow ovals indicated metal, bright in color because of their higher iron metal content, which caused them to reflect more clearly under the probes, said Linda Welzenbach, a museum specialist and the meteorite collection manager. The duller, almost mustard yellows, would indicate metal that had more iron sulfide, she explained.

But Corrigan flew past the yellow circles on the backscatter image in front of her, past the black fractures and dark gray, indicating rivers of feldspar, to zoom in on the lighter gray circles called chondrules, the crystallized mineral droplets that give chondrites their name.

Chondrites have higher amounts of iron, as opposed to the large amounts of calcium and aluminum found in lunar meteorites, bits of the moon that land on the Earth. Types of chondrites are distinguished by their total amount of iron, Corrigan said. They measure that amount with the probe, which detects the ratios of minerals called olivine, pyroxene and feldspar. The gem version of the olivine mineral is peridot (the birthstone for August) and the compound thought to make up most of the mantle of the earth. The "Lorton Meteorite" itself is likely an L chondrite, which has a low iron content, though Welzenbach was hesitant to identify it until all of the readings had been analyzed.

“Part of the reason we like to study in meteorites is that it will help us learn about earth as well,” she said.

Back in the Mason-Clarke Meteorite vault, where meteorites are stored, Linda opened the box that held the "Lorton Meteorite," broken into three pieces from the fall. Put together, the meteorite became almost whole again, with the missing chunk offering a glimpse of the sparkling interior. It’s similar to how visitors to the museum will see the meteorite if the Smithsonian gets to call itself the owner. The doctors' office where the meteorite was found turned it over to the Smithsonian for analysis, but according to today's Washington Post, ownership issues are complicating whether or not the museum will get to keep it for display.

Either way, the chance to analyze the meteorite is invaluable.

“It’s not everyday a meteorite lands in our backyard,” Corrigan said.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)