You Can Thank Scientists for the National Park System

Early conservation research and scientific expeditions laid the groundwork and helped to convince the public national parks were a good idea

The two volcanic rocks couldn’t be more different at first glance. The hyalo-liparite obsidian could be mistaken for a candy bar with large chocolate chips, while beside it inside the glass case, the geyserite more closely resembles white sidewalk chalk.

The rocks were collected on the expedition of scientists, photographers and painters that geologist Ferdinand Hayden led in 1871, the first federally-funded survey of the American west. They are on view in a new exhibition “100 Years of America’s National Park Service” at the National Museum of Natural History. They are examples of the many specimens that scientists, exploring the American West, sent back to the early Smithsonian Institution.

The show honors the scientific collecting that helped to lay the groundwork for the creation of the national park system one hundred years ago this summer.

“Volcanic specimens such as these—along with survey reports that the land wasn’t suitable for agriculture, mining, or settlement—convinced Congress to pass legislation to create Yellowstone, America’s first national park,” notes a label in the show, which was co-organized by the museum and the National Park Service.

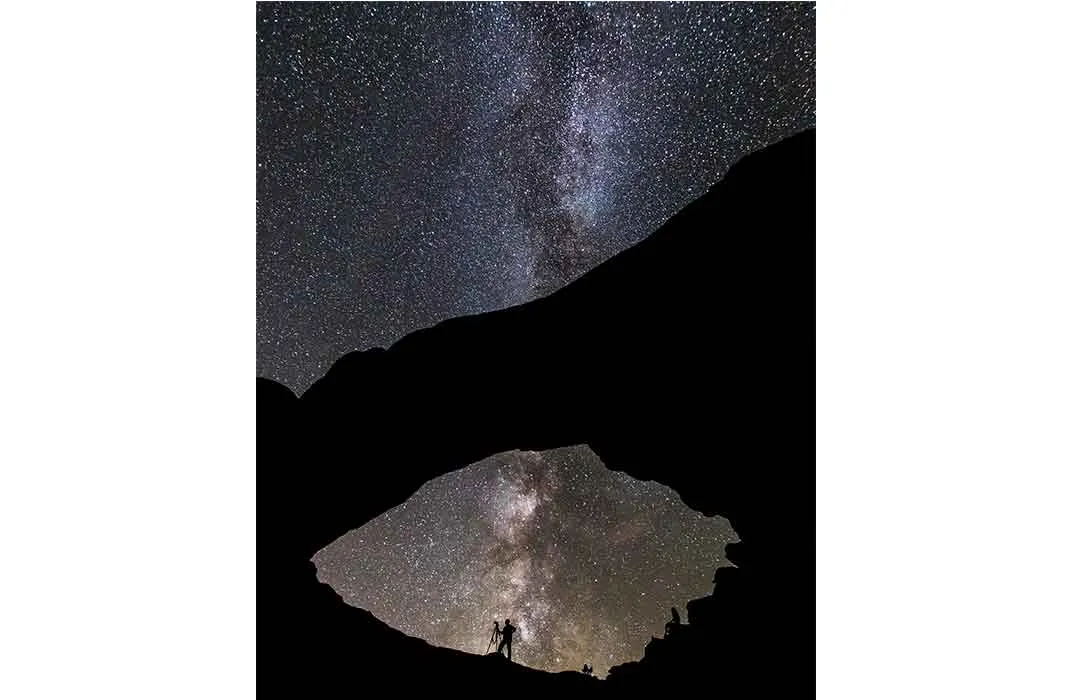

Surrounding the glass case housing the two volcanic rocks are contributions from 18 award-winning photographers, including a display of 15 gorgeous panoramic views created by nature photographer Stan Jorstad and 24 awe-inspiring images by Carol M. Highsmith of some of the most popular parks—Yellowstone, Yosemite, the Great Smoky Mountains, Grand Teton and Glacier National Park.

Scientists on expeditions conducting geological surveys of the west, says Pam Henson, an historian with the Smithsonian Institution Archives, were among the first to notice red flags in nature that suggested pathways to extinction of species if the status quo of human exploitation was allowed to continue.

One such scientist was William Temple Hornaday, a founder of the American Conservation Movement and chief taxidermist at the Smithsonian, who went out west in the 1880s to collect bison in the preserve that was later designated Yellowstone National Park.

“He goes out there, and he’s stunned because there are no bison,” says Henson. Instead, Hornaday found mountains of bison skulls.

Hornaday eventually found a small, remnant herd of the quintessential American species. “Over the time that he’s out there, you see in his correspondence essentially a conversion experience,” Henson says. “He’s like, ‘Oh my God. We have to preserve these things. They are iconically American.’” So Hornaday started a movement to preserve the American bison, a cause to which he devoted the rest of his life. He would later become a founder of the Smithsonian's National Zoo.

Hornaday brought live buffalo back to Washington, D.C., and started the Department of Living Animals. The bison grazed behind the red stone Smithsonian Castle Building on what’s now the Haupt Garden, and the animals became very popular.

Other scientists, such as John Wesley Powell who explored the Colorado River and the Grand Canyon, sent specimens back to the Smithsonian, and Powell became the founding director of the Bureau of American Ethnography. “The Smithsonian has close ties with all of these explorers,” Henson adds.

A historical account on the park service website explains, the service didn’t exactly start in 1872 with Congress’ creation of Yellowstone National Park. “Like a river formed from several branches, however, the system cannot be traced to a single source. Other components—the parks of the nation’s capital, hot springs, parts of Yosemite—preceded Yellowstone as parklands reserved or established by the federal government,” according to the site. “And there was no real ‘system’ of national parks until Congress created a federal bureau, the National Park Service, in 1916 to manage those areas assigned to the U.S. Department of the Interior.”

At first, the service faces opposition, notes Ann Hitchcock, a curator of the show from the National Park Service. “One of the debates in Congress was proving that this land was useless: not good for agriculture, mining or other kinds of developments. So you might as well preserve it, because it’s pretty unusual and interesting,” she says. “It’s a tremendous piece of our natural heritage.”

Hitchcock cites Franklin D. Roosevelt’s quote that “there is nothing so American as our national parks.”

Henson notes that two powerful forces were pitted against the scientific imperative to protect U.S. wildlife and habitats at the outset. Settlers didn’t like the idea of restrictions on hunting even at-risk species, fearing the decimation of their way of life. And the influence of churches held sway with clergy that preached from the pulpit that the earth and its herds had been divinely bestowed upon people to do with as they saw fit.

Early settlers felt that “God put all of this out there for man’s bounty, and that there was no inherent value in the forest, in the plants and animals, other than to serve mankind,” Henson says. “It’s a giant shift to say these things have an inherent value that humans should not disrupt.”

But the possibility of extinction eventually changed hearts and minds, says Henson. “Extinction really was shocking. You have the Carolina parakeet and the passenger pigeon. The bison, you’re right at the edge. Things go extinct,” Henson says. “There were so many passenger pigeons that nobody conceived they could go extinct. That really becomes a metaphor for human destruction of God’s creation in a way.”

In 1872, when then-president Ulysses S. Grant signed the bill into law, more than 2 million acres of land were set aside to become public parks. Paintings by artists like Thomas Moran had shown the public the splendor of the American west. Specimens that scientists sent back East had delivered a message on the cultural and geological significance of the land.

In 1832 following a trip to the Dakotas, artist George Catlin presciently wrote of “some great protecting policy of government . . . in a magnificent park, . . . a nation’s park, containing man and beast, in all the wild[ness] and freshness of their nature’s beauty!”

In much the way Catlin’s early vision of a national park didn’t directly pave the way for the National Park Service, the scientific expeditions didn't immediately create the conservation movement. But they planted the seed.

"100 Years of America's National Park Service: Preserve, Enjoy, Inspire" is on view through August 2017 at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/36/42/3642e94b-4fff-425f-8c81-ea187a48f744/vickweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)