The Youngest of the Little Rock Nine Speaks About Holding on to History

Carlotta Walls LeNier, whose school dress is in the Smithsonian, says much was accomplished and now we need to hold onto it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/3d/df3d0d26-c729-408c-b24c-48296c08ee22/101st_airborne_at_little_rock_central_highweb.jpg)

In the galleries of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, a singular black dress, printed with blue, white and sea-green letters and patterns, is on display. It seems more than appropriate attire for a young lady’s first day of school.

The dress once belonged to Carlotta Walls LaNier, who with eight other African Americans integrated Little Rock’s Central High school for the first time in September of 1957—an act that made the Little Rock Nine an indelible part of this nation’s contentious history.

“It was not an easy task, but we didn’t expect it to be as it turned out,” LaNier recalls. “You have to learn how to deal with adversity, and I think we all did.”

Adversity doesn’t seem quite a strong enough word to describe the experience of black teenagers braving an angry white mob of segregationists to go to school the morning of September 4, 1957, only to be turned away by armed Arkansas National Guardsmen under orders from Governor Orval Faubus.

After a legal battle, and a judge’s order to remove the National Guard, the Little Rock Police Department escorted the nine African American students into Central High through a furious mob of some 1,000 whites on September 23. But the students were removed after a few hours amidst chaos and rioting. LaNier wore her dress for both of what she calls the “two first days” of her sophomore year in high school.

“I want you to think about the fact that I was 14, number one. Number two, the underlying theme here in the foundation of this whole thing is really we had a right based on Brown v. Board of Education . . . and this was a Supreme Court decision,” LaNier explains. “My parents had always said to me ‘Be prepared to go through the door whether there’s a crack in the door or the door is flung wide open.’”

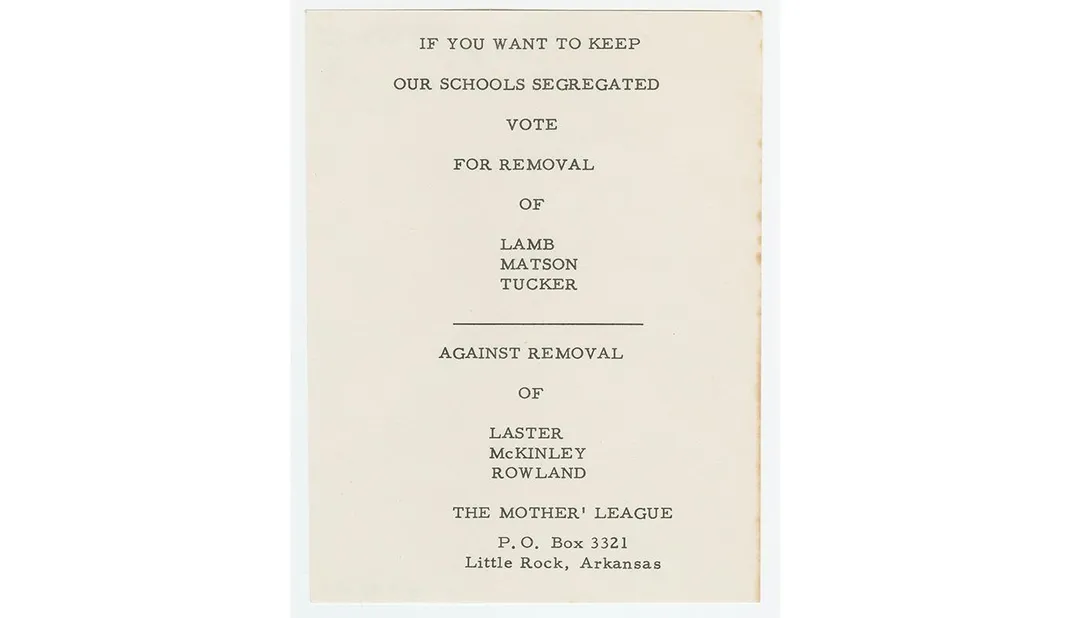

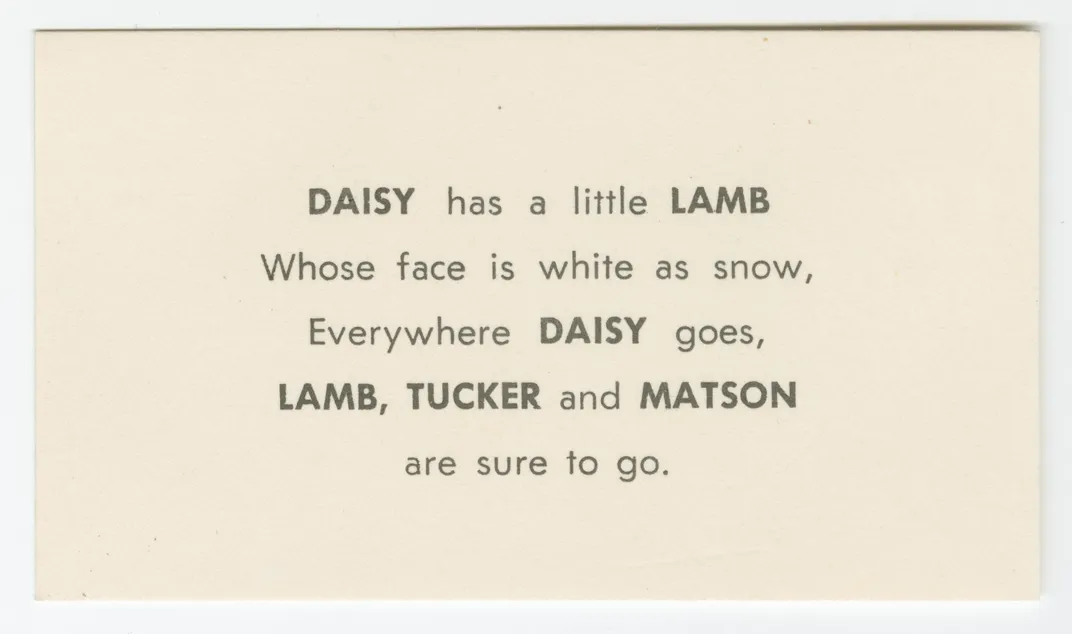

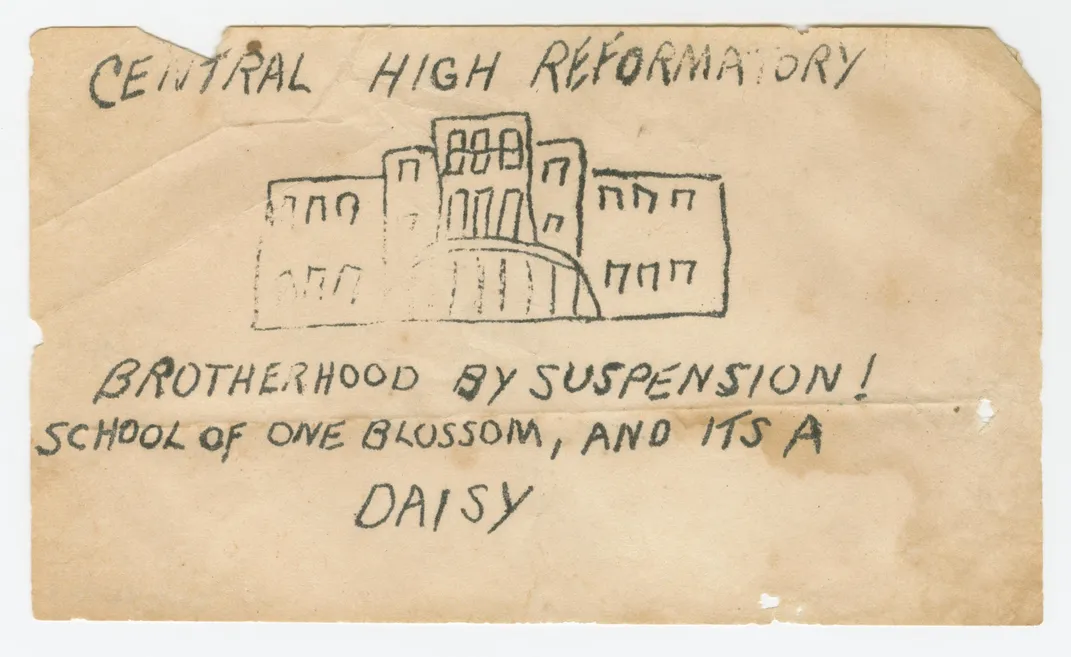

LaNier, now 74, was the youngest of the nine black students recruited by Arkansas NAACP President Daisy Bates to be the first African Americans to attend Central High School. This was in the wake of the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, in which the U. S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. In a related decision, the court ruled that all public schools in the nation be integrated “with all deliberate speed.” As Arkansas prepared to integrate the high school, LaNier and the eight other students received intensive counseling to ensure that they had the determination to endure likely hostile situations. She knew a new black high school was going to open, but LaNier wanted to go to Central High because it had better resources.

“It would at least give you that opportunity to have those books . . . . the most recent books. You have access to a better education, is what it boils down to. It had nothing to do with the fact that we had poor teachers. We had great teachers. They just didn’t have what was equal to what was over at Little Rock Central High School,” LaNier says.

Her parents didn’t even know she had signed up to attend Central High until her registration card arrived in the mail in July. LaNier remembers it as just a normal thing to do according to how she had been raised by her brick mason father and homemaker mother.

“My father’s eyes got large when he saw the postcard. . . . It was no big deal to me, and they were both rather proud of the fact that I had done that,” LaNier says. But her choice of school and the racial tensions surrounding the nine students did affect her family. “My father lost every job . . . once they found out who he really was. One thing after another. So it was tough on them, but they remained supportive. I’ve said so often in presentations that the real heroes and sheroes are the parents.”

She says until you become a parent, you don’t know what kinds of things you will allow your child to be part of, and whether you will allow them to participate.

“Now my folks really didn’t know and neither did the other parents, but they supported us. They didn’t want to be quitters either,” LaNier explains. “We were kids going to school, being harassed, being bullied from one extreme to another but we persevered.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/38/763805c9-ffca-41a3-8c52-8e5f7cd066c2/nmaahc-2011_17_201.jpg)

LaNier and the other students, Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Thelma Mothershed, Melba Pattillo, Gloria Ray, Terrence Roberts and Jefferson Thomas, endured a plethora of daily insults and worse. Pattillo was kicked and beaten, white students burned a black effigy in a vacant lot across from the school, and Ray was pushed down a flight of stairs. But simply getting into the school building was a challenge LaNier says few expected because Little Rock was considered to be a moderate city.

Two days before school was set to open, Governor Faubus announced he was calling in the Arkansas National Guard to protect citizens from the violence he feared would break out if the black students were allowed inside. LaNier remembers her father going to work September 4, and her mother dropping her off with a group of ministers the NAACP had enlisted to escort the teens to the school. Eight arrived together. But Eckford didn’t know about the plans and arrived alone. There’s a picture of her, notebook in hand, approaching the school surrounded by a screaming crowd of white adults and students.

“Then, once we got to the corner of the school, that’s when the National Guard closed ranks. Then finally the commanding officer came up and said . . .‘take these kids back home,’” Lanier says, still sounding furious. “‘Well what do you mean?’ we asked. That’s when we knew they were really there to keep us out, not to protect the citizens of Little Rock.”

After a federal court battle raged for weeks, led by NAACP lawyer (and eventual U.S. Supreme Court Justice) Thurgood Marshall, federal Judge Richard Davies ordered the National Guard removed from the school. On September 23, LaNier’s second first day, Little Rock Police escorted the nine black students through a frothing crowd of about 1,000 whites.

“We went in through a side door, some field marshals of the NAACP and some fathers of the Little Rock Nine. . . . That was like 8:30 in the morning, and by 11:30 they had spirited us out of there. . . The city sent Little Rock’s finest there, which was about 17 of them. That’s all they had to be around the school, and they couldn’t hold back that many people,” LaNier remembers. “Kids were jumping out of windows and others were saying ‘Get one of them, let’s hang them.’”

LaNier was in the rear of the school in geometry class when the police came to remove her, and she says she didn’t see any of that until it was on the evening news.

“It was on the radio, too, I guess because my mother was standing in the yard when the policeman dropped me off. She had gotten a number of phone calls from her sister and from my great aunts and so forth to ‘go up and get (me),’ but there was no way she could have done that anyway. And the gray hair she has on her head. . . started that day,” LaNier says.

On September 24, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent in 1,200 members of the U-S Army’s 101st Airborne Division and put them in charge of the 10,000 National Guardsmen on duty. The Little Rock Nine were escorted by troops to their first full-day of classes on September 25.

“We were taken to school every day in a military station wagon with a Jeep in front and a Jeep in the back. Guns, they were all up and down the hallways,” LaNier says. “I tell kids today I had a helicopter buzzing over my school. Twelve hundred troopers bivouacked on campus. . . I don’t ever want to see that happen for them or any other educational institution. That’s not the way to go to school.”

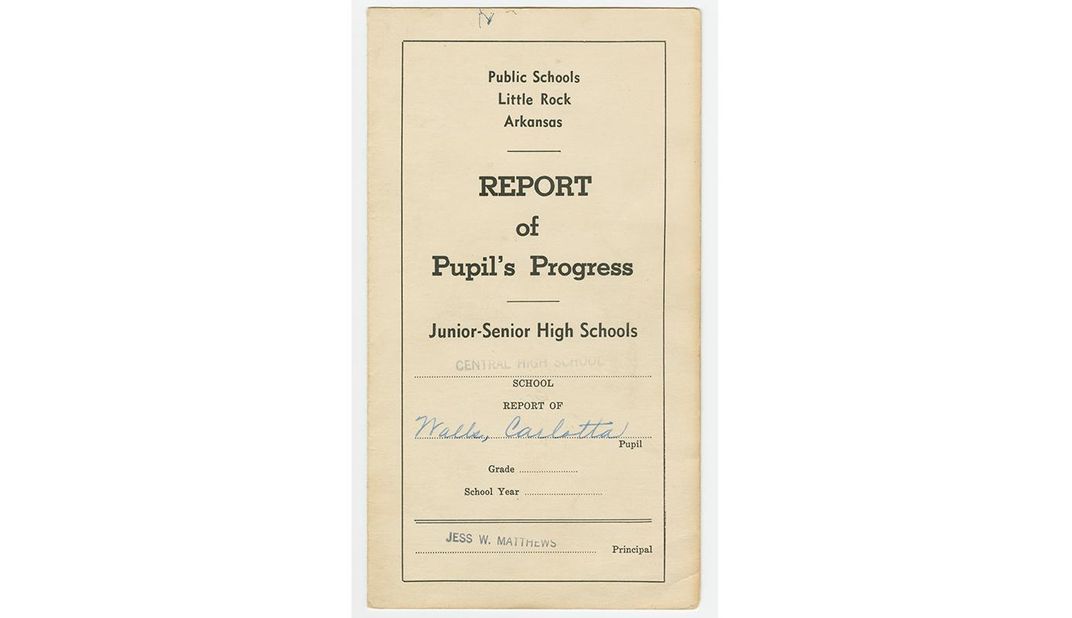

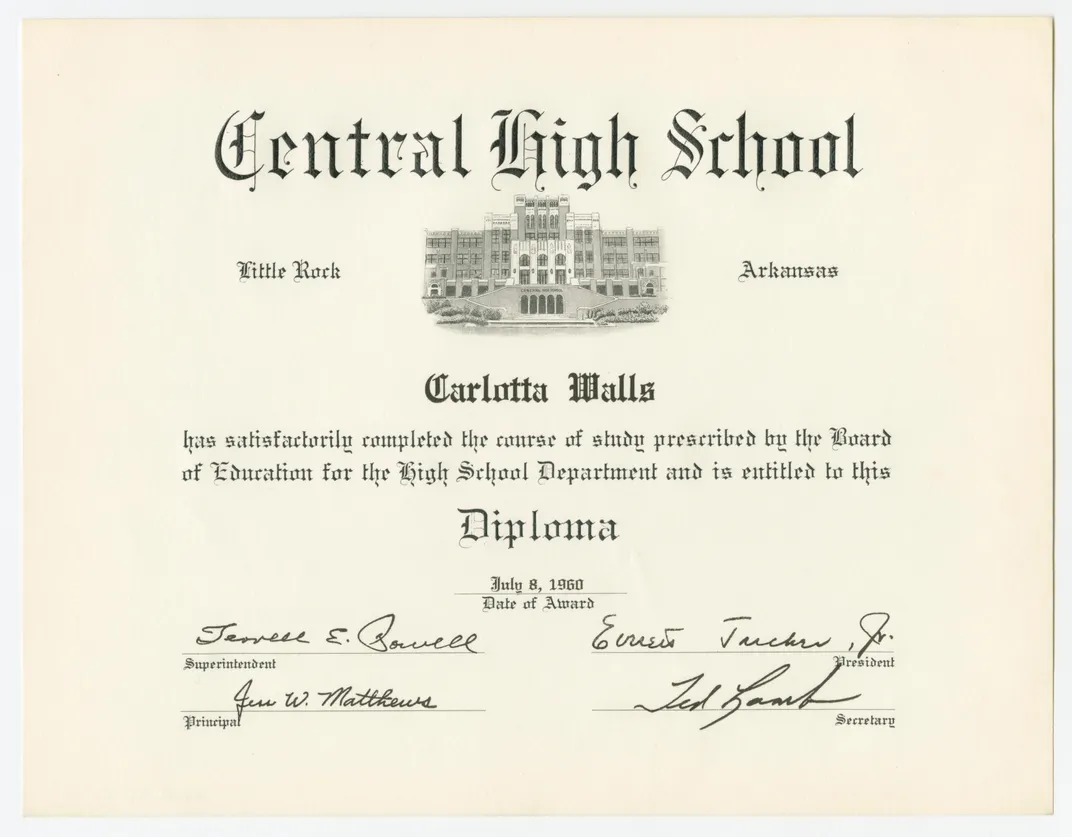

In May of 1958, Ernest Green became the first African American graduate of Central High. But Governor Faubus closed Little Rock’s high schools for the entire year to keep blacks from attending, and they didn’t reopen until August of 1959. LaNier returned to Central High and graduated in 1960.

LaNier says the dress she wore on September 4 and 23 was store-bought, rather than one of the garments made by her mother, an expert seamstress who made clothes for everyone in the family. Her great-uncle Emerald Holloway felt that she should have something special for her first day integrating the formerly all-white Central High.

“Uncle Em came by the house and gave my mother $20, and he said ‘I want you to buy her a store-bought dress. I want you to take her downtown and buy her a new dress to go to school.’ . . . I went downtown with her to pick it out,” LaNier says.

But LaNier didn’t discover her mother had kept the dress until around 1976. LaNier loaned it to the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit for a time, and considered several other options. But then, she decided to donate it to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, along with her diploma and a report card from Little Rock Central High. She says she thought about how her children and so many others around the country visited the Smithsonian museums to learn about the nation’s history.

“I think these kids need to know this history. You know they don’t have civics in school anymore. They don’t have history, and they don’t make them take history classes,” LaNier says. “When you really look at the history of this country, we know we live here 335 years in one way in this country and Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, it changed all of that.”

LaNier says the progress in this nation, including the Civil Rights Act and other legislation including the Voting Rights act, all stem from that foundation.

“Yes, we had it rough. We could’ve been killed. My home was bombed. I mean, I’ve been through a lot,” LaNier says. “So here we are, 63 years later. You compare 63 years to 330-plus years of living one way, and you see we have accomplished a great deal. Now we have to hold onto it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)