Rare, Centuries-Old Korean Buddhist Masterpiece Goes on View

Sealed and hidden within the sculpture were sacred texts and symbolic objects

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/65/3e6504a0-235b-4d20-afa2-7a1f658c66a7/duk000953-01crop.jpg)

A Buddhist seeking care and kindness will often turn his or her prayers to Gwaneum, the bodhisattva of compassion. Bodhisattvas—beings who have reached enlightenment but stay connected to the material world to help humanity—are not unlike Christianity’s saints, figures associated with positive traits or attributes to whom people can turn in times of need.

A 13th-century sculpture of Gwaneum, once displayed in a Buddhist temple in Korea, now takes center stage at the Sackler Gallery of Art. On loan from the National Museum of Korea, the statue is the focus of the new exhibition “Sacred Dedication: A Korean Buddhist Masterpiece.”

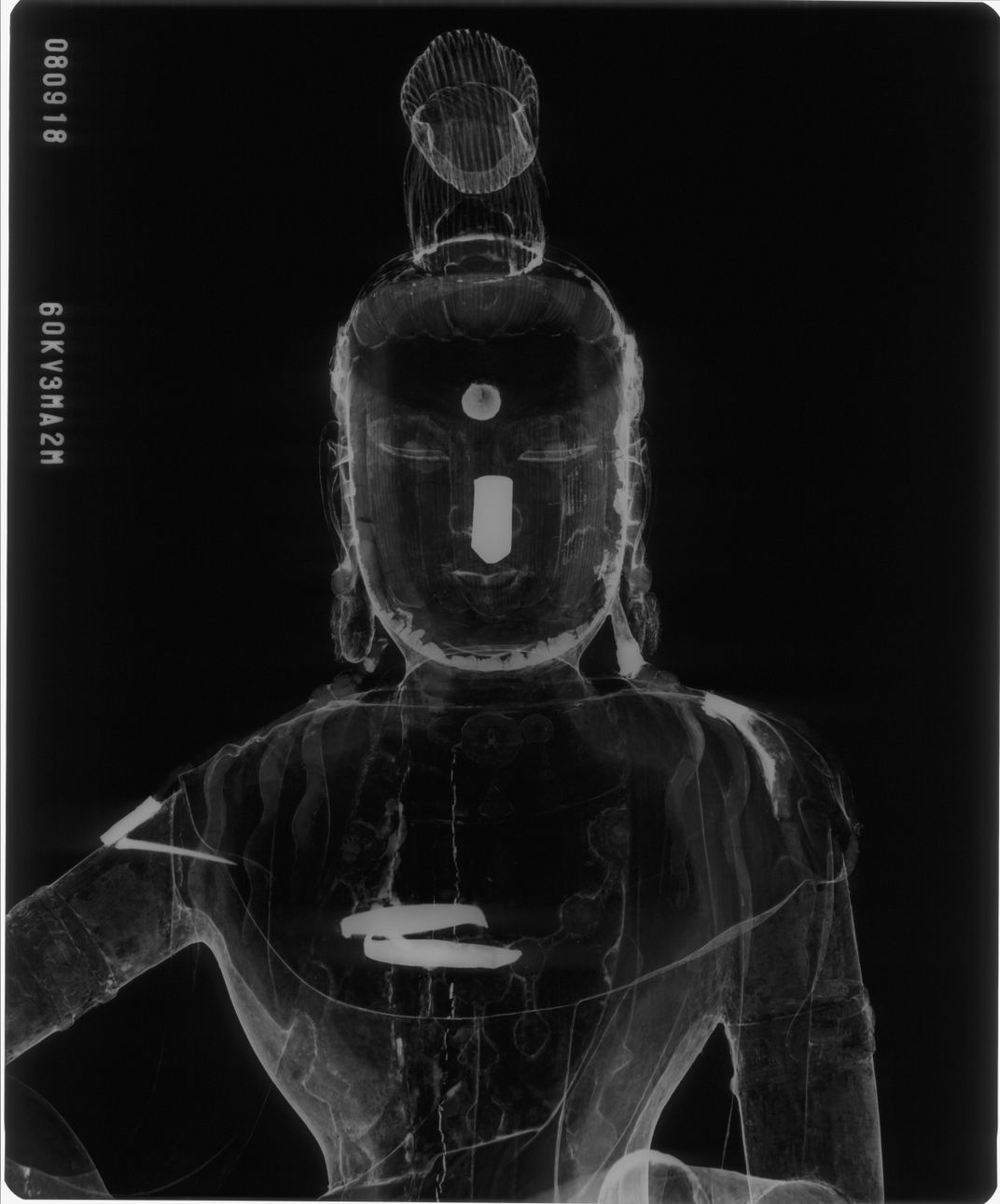

The two-foot tall gilded wooden figure is constructed of 15 pieces of fir, stapled and nailed together. A separate, elaborate metal crown is placed on its head, just above the forehead’s urna, which represents the third eye or vision into the divine world. Reclining in an informal pose, associated with the deity’s dwelling place on the waves above the sea, the sculpture’s right arm is extended and its left arm is bent, resting in mid-air, indicating that it might possibly have been originally placed on a carved wooden platform in a temple.

Gwaneum, also known as Avalokiteshvara in Sanskrit, is the most popular bodhisattva in East Asia. Chinese examples of the figure are well known—some are even on display across the hall at the Sackler’s ongoing exhibition “Encountering Buddha: Art and Practice Across Asia,” but few of these statues still exist in Korea. This one, which dates from the Goryeo dynasty (918-1392), is the oldest surviving sculpture of its kind in its country.

Buddhism reached Korea in the fourth century, and by the time this sculpture was created in the 1200s, it was widespread and had royal support. The rich materials of the sculpture, from its gold covering to its crystal urna, suggests it was created in a workshop of highly-skilled woodcarvers and gilders. “During the Goryeo period, you have very strong royal patronage for the Buddhist institution and for image-making,” explains the museum’s Keith Wilson, who co-curated “Sacred Dedication” with Sunwoo Hwang, a student from Dongguk University in Seoul and a fellow at the museum.

Sculptures of Gwaneum were popular in Korea but only a few survived invasions that the country underwent, explaining in part the deity’s lasting appeal for the masses and for rulers alike, explains Hwang. As Korea suffered wars and occupations, much of its material culture, including these types of sculptures, were destroyed.

In the 13th century, the Goryeo kingdom capitulated to the Mongols and became a semi-autonomous state. Its royals, including the crown prince and princess, were later forced to live in Beijing. “It’s a trying time for Korea,” says Wilson, the museum’s curator of ancient Chinese art. Gwaneum “as a compassionate protector might have had special meaning in this time for the court.” He explains, the bodhisattva is “meant to be an approachable figure, someone who can advocate for us within the Buddhist pantheon, maybe even answer prayers or needs.”

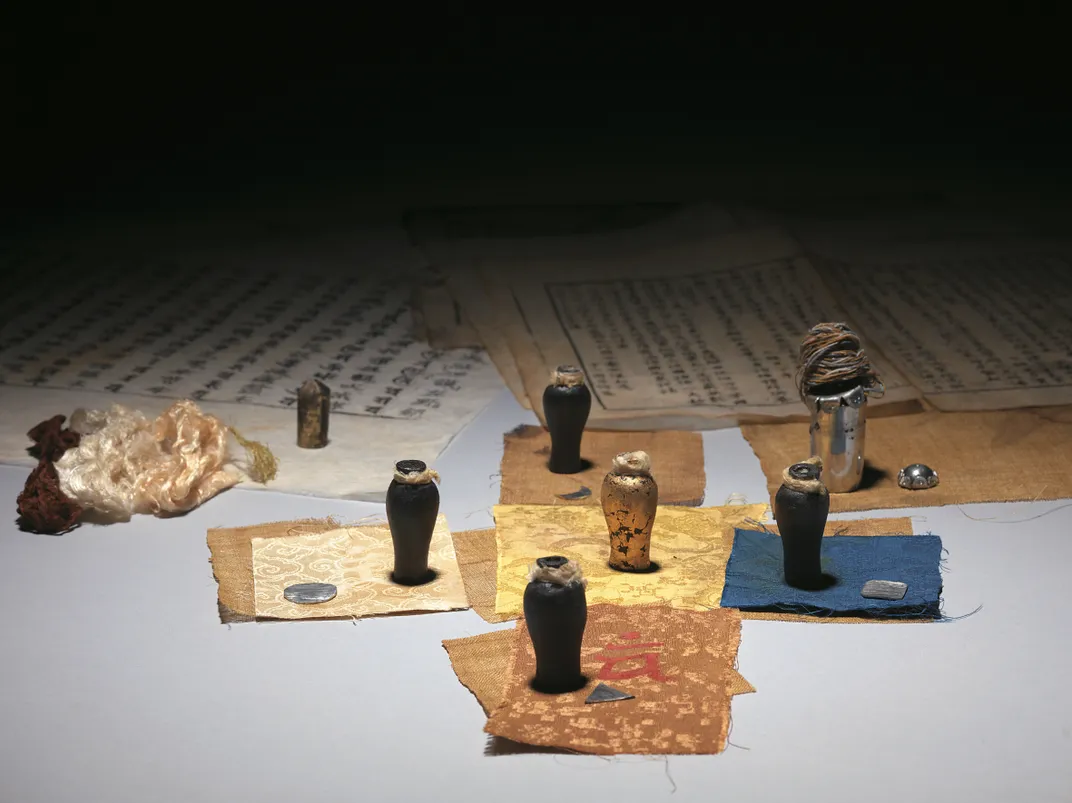

When the sculpture was completed and dedicated in the 13th century, sacred texts and symbolic objects were placed in it, both in its head and its body. “The idea was the relic and the dedication materials gave the sculpture spiritual life for believers,” says Wilson. The materials transformed the sculpture so it was “not just a piece of carved wood . . . It had a kind of spiritual force from the material that was placed inside.”

Recent research, including X-rays and material analysis by the National Museum of Korea, shows that the sculpture includes contents from different time periods, indicating that it was opened up and re-dedicated at least once. The dedication materials have been temporarily removed and are on display alongside the sculpture, with explanations of their symbolic meaning. A 3D scan by Smithsonian Institution’s Digitization Program allows viewers to visualize the sculpture’s construction and the contents’ original placement. Hwang is especially excited to be able to share with visitors the lesser-known context of the consecration rituals. In February 2020, in conjunction with a symposium on the exhibition, Korean Buddhist monks will demonstrate a contemporary dedication ritual.

This is the first time this sculpture has been shown outside Korea, and Hwang and Wilson see it as a complement to the museum’s “Encountering the Buddha” show, which doesn’t include any examples of Korean sculptures. The loaned statue is placed opposite a scroll from the Freer|Sackler’s collection, depicting Gwaneum in his dwelling place on the rocks above the sea’s waves and being visited by a pilgrim on his way to enlightenment. The ability to place two rare depictions of Gwaneum, made within a century of each other, is a special opportunity for Wilson and Hwang and one they relish sharing with visitors to the museum.

“Sacred Dedication: A Korean Buddhist Masterpiece” is on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. through March 22, 2020.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/6d/ec6d3673-d5d9-4165-9570-2cc57517c8ba/duk000953-02.jpg)