Taking a Cue from Textile-Making to Engineer Human Tissue

Researchers in search of a faster, cheaper way to engineer human tissue found success in traditional textile production methods.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2d/b9/2db9c425-2c82-4f14-8f40-652341ab71ec/fabric_in_loom.jpg)

Engineered human tissue plays a small but growing role in medicine. Engineered skin can be used on surgical patients or burn victims, engineered arteries have been used to repair obstructed blood flow and entire engineered tracheas have even been implanted in patients whose airways were failing. As the science progresses, researchers hope to be able to engineer entire organs, such as hearts or livers.

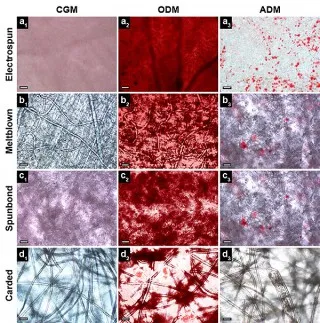

But tissue engineering is not easy. It involves first creating a “scaffold” to grow the tissue on. The scaffold is typically made through a process called “electrospinning,” which involves using an electrostatic field to bond materials together. In some cases, the scaffolding can be implanted along with the tissue, and it will dissolve in the body over time. But electrospinning can be a slow and costly process, making it difficult to create tissue on the large scale needed for medical research and applications.

What if, researchers wondered, making scaffolding was as easy as, say, making socks?

“We started thinking, ‘could we look at some other industry standard practices that make other materials, like textiles?’” says Elizabeth Loboa, dean of University of Missouri's College of Engineering.

Reasoning that textiles and human tissues are not so different, Loboa and her team worked with researchers at the University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University’s College of Textiles to investigate the scaffold-building potential of traditional textile manufacturing processes.

The researchers investigated three common textile-making methods—melt blowing, spunbonding and carding. Melt blowing involves using high-pressure air to blow hot polymer resin into a web of fine fibers. Spunbonding is similar, but uses less heat. Carding separates fibers through rollers, creating a web of textile.

“These are processes used very commonly in the textile industry, so they’re already industry standard, commercially relevant manufacturing processes,” Loboa says.

The team used polylactic acid, a type of biodegradable plastic, to create the scaffolds, and seeded them with human stem cells using the various textile techniques. They then waited to see if the cells began to differentiate into different types of tissue.

The results were promising. The textile techniques were effective and more affordable than electrospinning. The team estimated a square meter of electrospun scaffolding costs between $2 and $5, while the same-sized sample made using textile techniques cost only $0.30 to $3. Textile techniques also work significantly faster than electrospinning.

The team’s next challenge will be to see how the scaffolds work in action, which will involve animal studies. The researchers also need to reduce the fiber size of the textile-produced scaffolding to better resemble the extracellular matrix of the human body, or the network of molecules that support cell growth. Electrospun scaffolding produces very small fibers, which is one of the reasons it’s such a popular method; the textile methods seem to produce larger fibers.

In the future, Loboa hopes to be able to produce larger quantities of scaffolding to grow human skin, bone, fat and more. These tissues could help repair limbs for wounded soldiers, Loboa says, or help babies born without certain body parts.

“We have to really figure out ways to get these to be successful in our patients,” she says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)