Talk to almost any Charleston-based historian, and you’re almost certain to hear stories about midnight rides, dramatic speeches, and fierce battles that shifted the outcome of the war—the Revolutionary War, that is.

“You know, there was as much protest with the Stamp Act here in Charleston as there was in Boston or New York,” says Carl Borick, executive director of the Charleston Museum complex, which includes a historic house once occupied by a Colonial Charlestonian who fought for American independence. That’s a point seconded by Tony Youmans, who brings Charleston history to life at the Old Exchange & Provost Dungeon. “The last 18 months of the American War for Independence were almost entirely decided here in Charleston—more battles are fought in South Carolina in those 18 months than in all the other states combined!”

For history lovers, Charleston has long been a must-visit destination, and more than ever, the city’s Revolutionary past is coming to life at museums and national parks. Below, we’ve put together an itinerary that invites you to explore Charleston as it was in the early days of the American Revolution—and the American republic.

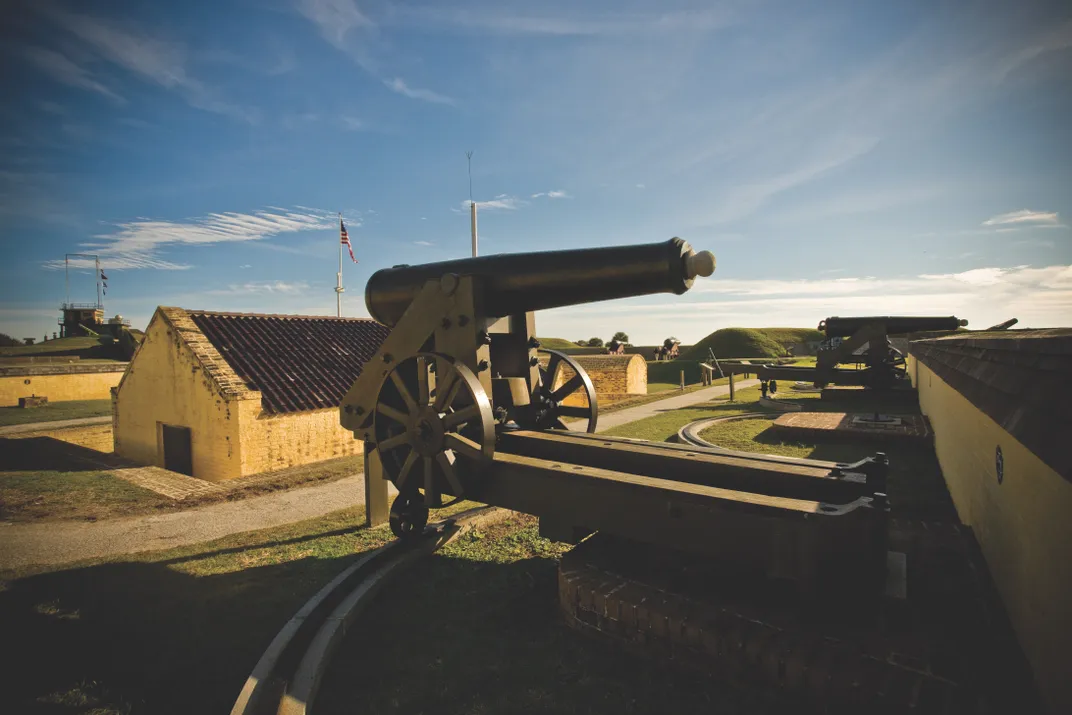

Fort Moultrie National Historic Park

The palmetto tree adorns South Carolina’s state flag, and once upon a time, its wood defended the fledgling city of Charleston (in colonial times known as Charles Town) from would-be intruders. At Fort Moultrie National Historic Park, visitors can see a model of the original palmetto log and sand fort that was only half-built when, in 1776, Commodore Sir Peter Parker, captaining a fleet of nine ships, attempted to take the city by sea. “The British viewed Charleston as a gateway to the South,” says Dawn H. Davis, the public affairs officer of Fort Moultrie and a thirty-year veteran of the National Park Service. “They actually thought there was a lot of loyalist support here to come into Charleston, and that it would be an easy thing, to come through a half-finished palmetto log fort and invade the South.” The fort, though, held strong, and Parker and his men were forced to retreat.

While the British did successfully invade Charleston in 1780, Fort Moultrie itself continued to serve as a valuable defender of the coastline through World War II, and today, the site interprets its rich history all the way through its decommissioning in 1946, letting visitors travel back in time to imagine the original palmetto log fort and its successors.

Old Exchange & Provost Dungeon

The Old Exchange & Provost Dungeon has been at the center of Charleston history since its erection in the early 1770s. “It was meant to be an ornament on the water,” says Tony Youmans, executive director of the building’s museum, now owned and operated by the Daughters of the American Revolution. “So when you sailed into Charleston Harbor, this was the first major building you saw. You saw two church steeples, St. Phillips and St. Michael's, and then you spied the Exchange Building, and you knew that you were in Charleston.”

Costumed interpreters guide visitors on a journey through Revolutionary Charleston, with the building taking a starring role: in 1788, South Carolina politicians held meetings about the U.S. Constitution and the colony’s role in the new republic. Just two years later, when British forces captured the city, the Exchange was used as a prison for Continental soldiers and officers.

Visitors to the site also learn about its actual construction, much of which was done by enslaved laborers, and of the symbolism the building would have had as the most common destination for public slave auctions in Charleston.

Visiting the space is like walking through history itself: “you've got all the original brick,” says Youmans. You're going to walk on the same bricks, the same floors that prisoners, all of the people who came through and near this building walked.”

Heyward-Washington House

Built in 1772, the Heyward-Washington house was the longtime city home of Thomas Heyward, one of four Declaration of Independence signatories from South Carolina. Today part of a complex that includes another historic house, as well as the Charleston Museum, the home boasts a number of historic home décor pieces, including the Holmes Bookcase, an intricately-carved 1770 library bookcase widely considered one of the most important pieces of furniture from the Colonial era.

The staging of the house captures, for modern-day visitors, the feeling of Revolutionary-era Charleston life. The Holmes Bookcase, says Charleston Museum director Carl Borick, “is now in what we know as the card room, or the drawing room, and that was the room where gentlemen would go and play cards and smoke and drink. We think that could have been the room in the Heyward-Washington House where Patriots were holding some of these clandestine meetings.”

And while in the 1770s the house might have been known as the Heyward house, it got its second name from a very important visitor: “President Washington,” Borick explains, “did a tour of the Southern states after he was elected president because he wanted to unify the country, and he stayed at Thomas Heyward's house.” Many notable Charlestonians visited Washington at the house, and today visitors tour these same spaces, including the bedroom where the first president slept.

Middleton Place

About fifteen miles northwest of Charleston, Middleton Place is a plantation that was once home to the Middleton family—Henry Middleton was president of the First Continental Congress, and his son, Arthur, signed the Declaration of Independence and was later a British prisoner of war held in St. Augustine, Florida.

The building itself was ransacked by British troops during the siege of Charleston, and parts of the main house were burned by Union soldiers during the Civil War. Now a landmark on the National Register of Historic Places, the house and grounds (which include the oldest landscaped gardens in the United States) interpret the stories of both the Middleton family and the many enslaved people who lived and worked there. “We have the names of enslaved people—Hercules, Tom, Will, Mary,” says Jeff Neale, Middleton Place’s director of preservation and interpretation. “And we have traced many of them beyond the house, beyond their time here. We know many people enslaved here ran away—to the North, to join up with the British in an attempt to seek freedom. The Revolution was, for many enslaved people, an opportunity to exercise their own rights as humans. And it’s important to us to tell as many of these stories as we can.”

Powder Magazine

Right in the heart of historic Charleston’s downtown, the Powder Magazine is one of the city’s oldest buildings. Built in 1713, it was once upon a time a storehouse for gunpowder, making it an important location for both British troops and loyalists and those colonists and soldiers who fought on the side of the new nation. After the war, as the Charleston landscape shifted, the small building remained standing, and served as—amongst other things—a print shop, a livery stable, and even a private wine cellar.

Today, the National Society of The Colonial Dames of America own the building, and it is open to the public as a military history museum that takes visitors back to Charleston, circa 1781, as the city and its residents considered what it might mean to leave the British empire behind.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/8a/cf8a9f98-5eed-45d2-9433-dbca896fc983/middleton_2017_house_01_copy.jpg)