What shape do you think of when you hear the word pasta? Macaroni. Ribbons and strands. Bowties. Tubes. Stuffed pockets. The Italians invented over 1,300 shapes of pasta, according to food scholar Oretta Zanini De Vita’s Encyclopedia of Pasta. Of course, like nonna’s dearest grandchild, there are multiple names for each shape. For example, cavatelli, meaning “little hollows” in Italian—and looking like little hot dog buns—goes by 28 different names depending on the region and town where you’re eating it.

Different shapes of pastas serve different purposes. They pair with an array of sauces: thicker sauces such as bolognese for tagliatelle, or flat ribbons of pasta; and lighter sauces such as lemon butter herb with farfalline, a small, rounded version of the traditional bowtie pasta. Rigatoni are short tubes of pasta with a ridged exterior—a shape great for chunky sauces that can fall into the ridges and the center of the tubes. And what’s the perfect pasta pairing for homemade pesto? Trofie. Herbs, oil and cheese cling to the crevices of the short, thin, twisted noodle. Then, of course, large pasta shells and pocket pastas, such as tortellini, serve a specific function, as a vessel for their cheese or meat-based filling.

Making Pasta

The various shapes can be categorized based on the means by which they are formed: by hand, rolled into sheets, or extruded. For each pasta making method, there have been a number of inventions to ease and mechanize the process.

Pastas formed by hand have been the most difficult to replicate by machine because of the complexity of the actions done by hand. Cavatelli, gnocchi and orecchiette, for example, are made by rolling pasta dough by hand into a long snake shape, cutting it into equal sized dough pieces, and dragging the dough to form a cup like shape. With cavatelli and gnocchi, the dough is dragged against a fork or grooved surface with a thumb to form a curled dough piece in the shape of a hot dog bun; the only real difference between the two is the dough. Gnocchi is made from a dough containing eggs, flour and cooked potatoes, whereas cavatelli are typically made from an eggless semolina wheat dough. Orecchiette, Italian for “little ear,” are made by dragging the dough pieces against a flat surface using a small spatula or knife, followed by a little hand shaping to round it out.

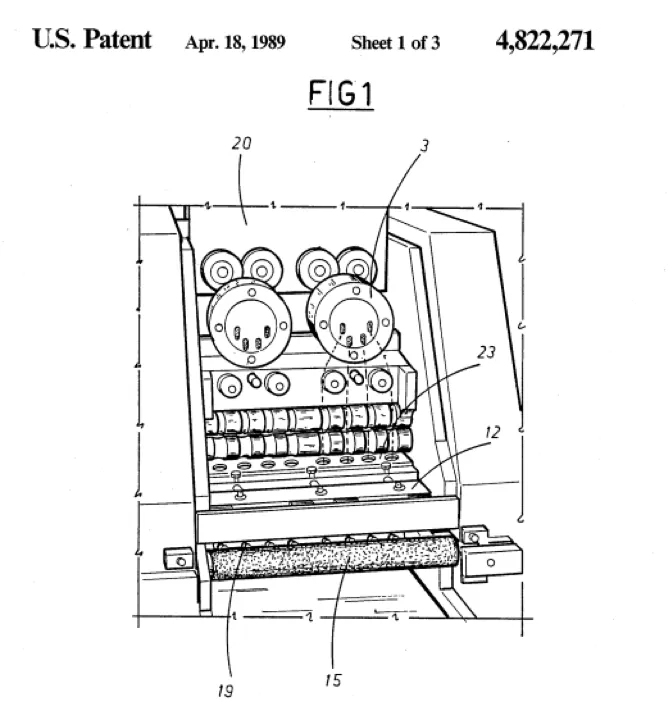

Italian inventors Franco Annicchiarico and Adima Pilari, who received U.S. patent no. 4,822,271 on April 18, 1989 for “an improved machine for manufacturing short cut varieties of Italian pasta (orecchiette, etc.),” developed a machine for making these cupped pastas. Comprised of three units, this patented invention allows users to feed the machine with pasta mix that later extrudes into sticks of pasta. Those sticks are then “cut into cylindrical pellets,” and finally, three rollers flatten, curl, rotate and form the pasta into a cup shape.

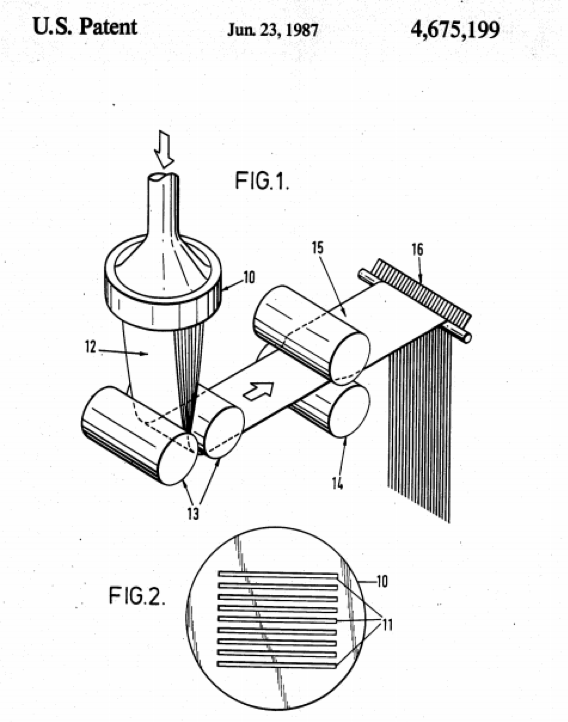

In a second method, dough is rolled out, cut into shapes and sometimes folded, as is the case with ravioli, lasagna noodles, and wide flat pasta noodles, such as tagliatelle and farfalle. On June 23, 1987, inventor Jau Y. Hsu of Brookfield, Connecticut received U.S. patent no. 4,675,199 for a process of cutting pasta shapes from sheets of dough. With the invention, “flour is mixed with from 15% to 33% by weight of water based on the weight of flour and water to form as dough,” and three nozzles create three sheets of pasta dough, which are then compressed and cut into the desired form. A year later, Italian inventor Enrico Fava was granted U.S. patent no. 4,769,975 for “a machine for the packaging of food products of flat, wide type, in particular lasagne.” This machine provides the positioning and cutting of pasta, such as lasagna sheets, and then feeds the sheets into coupled trays, stacking the layers of pasta. The invention makes it easy for a user to move the layered pasta to equipment that can hold the pasta until it’s ready for packaging.

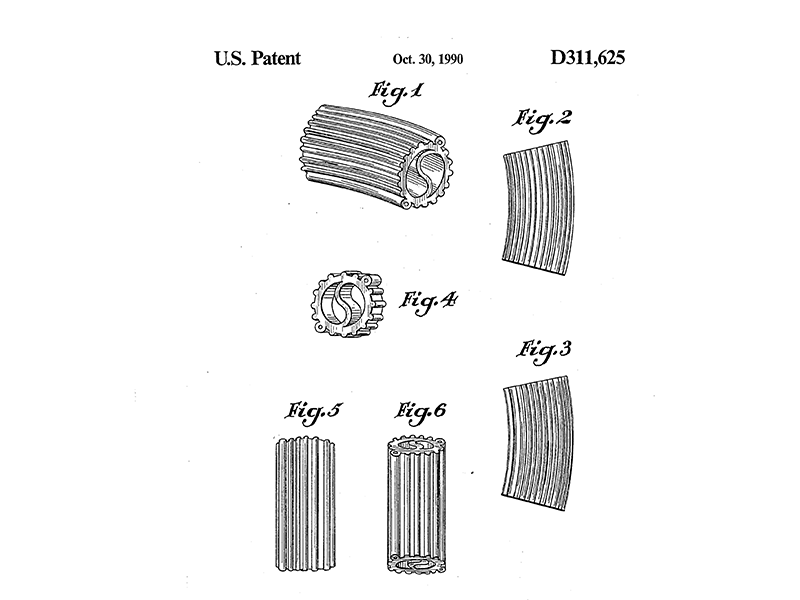

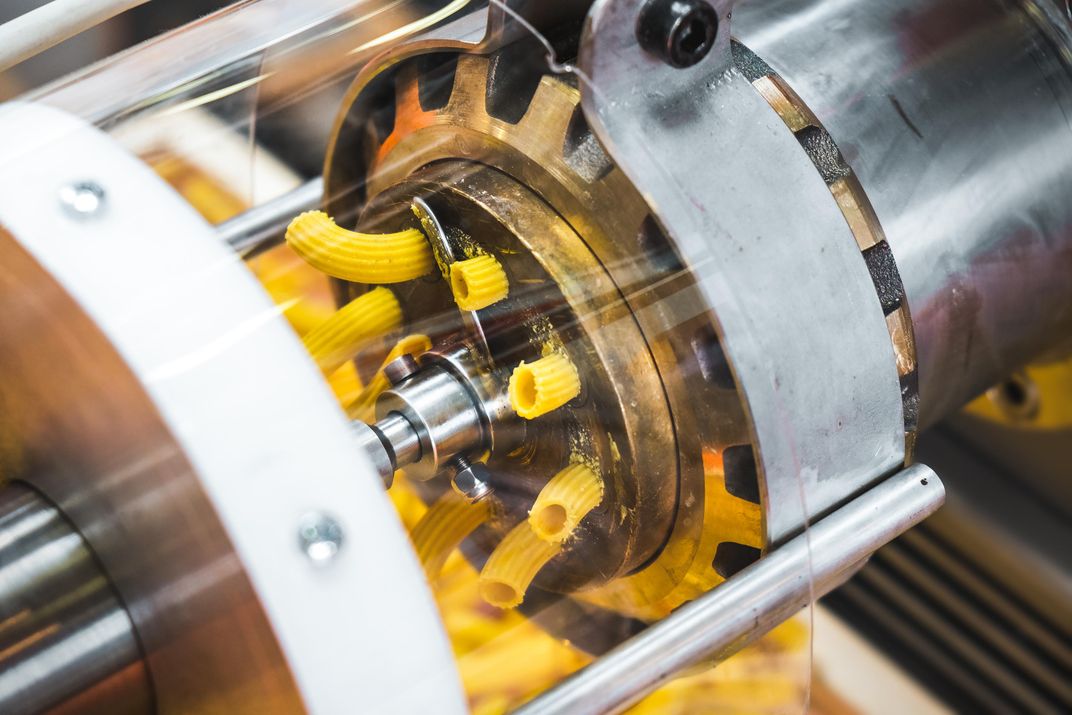

A third method for forming pasta is via extrusion, meaning dough is forced through an extrusion die and cut to length. Macaroni, rotini, penne, fusilli and rigatoni are all produced this way; the only real difference is the shape of the holes in the extrusion die. Flat shapes, such as lasagna, which are traditionally made by rollers or a rolling pin can also be formed by extrusion using a die with a slot shaped opening. Spiral shaped pasta is made by dies that have angled slots that cause the dough to spin as it is extruded. Hollow shapes and other complex shapes are made from dies cut like stencils, in which the die has a solid area for the hole to be, and bars that hold it in place but back far enough in the die that the dough forms around it.

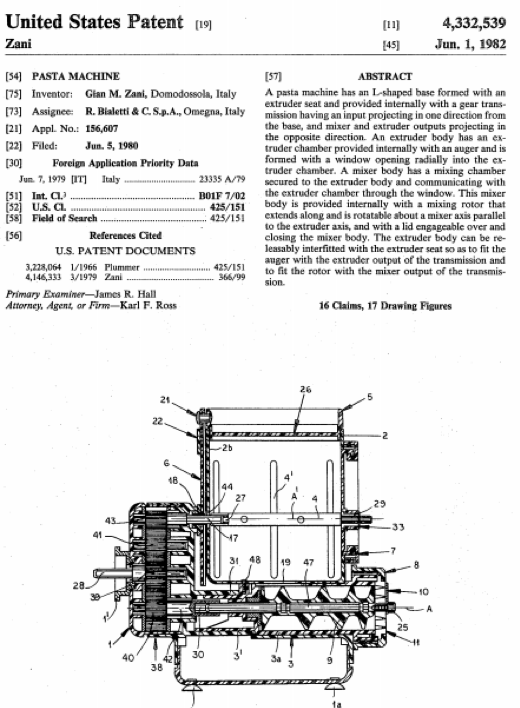

When it comes to this technique, there have been innovations in the machinery to produce the pasta as well as the shapes themselves. U.S. patent no. 4,332,539 is for a machine that does it all—mixes, shapes and extrudes the dough into pasta shapes. For those who prefer spaghetti or Japanese “Udon” noodles, U.S. patent no. 4,752,205 describes a machine that extrudes elongated strands of pasta with groves.

Whimsical Shapes

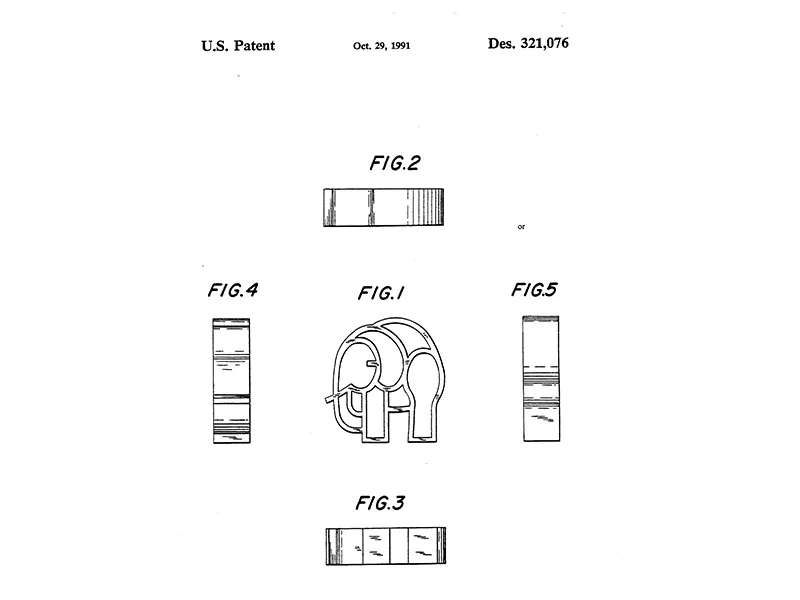

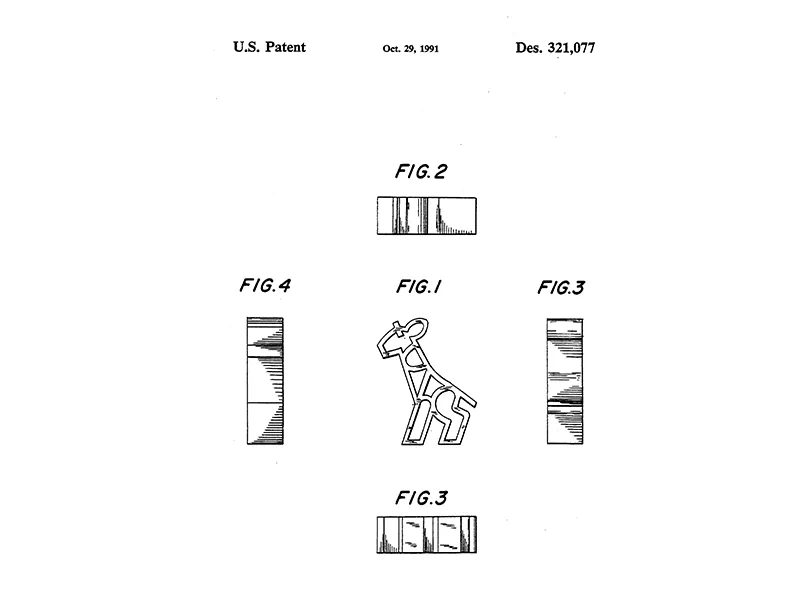

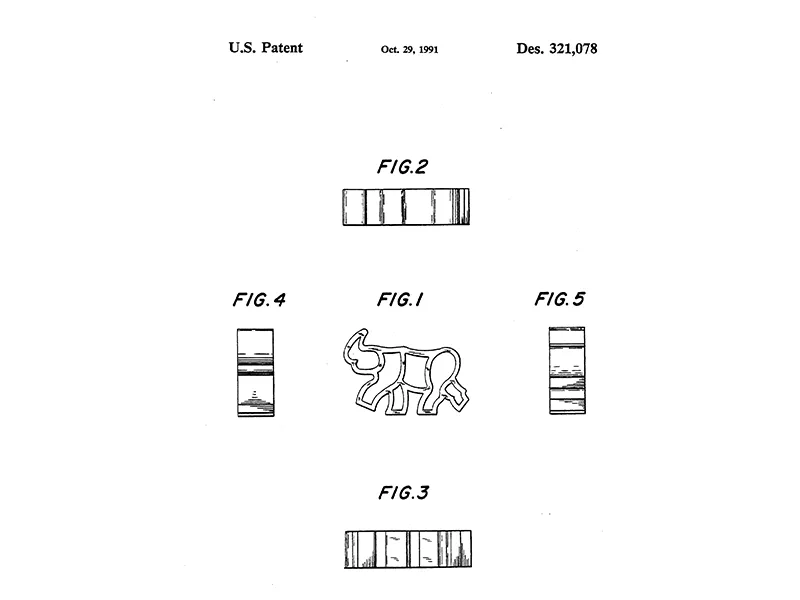

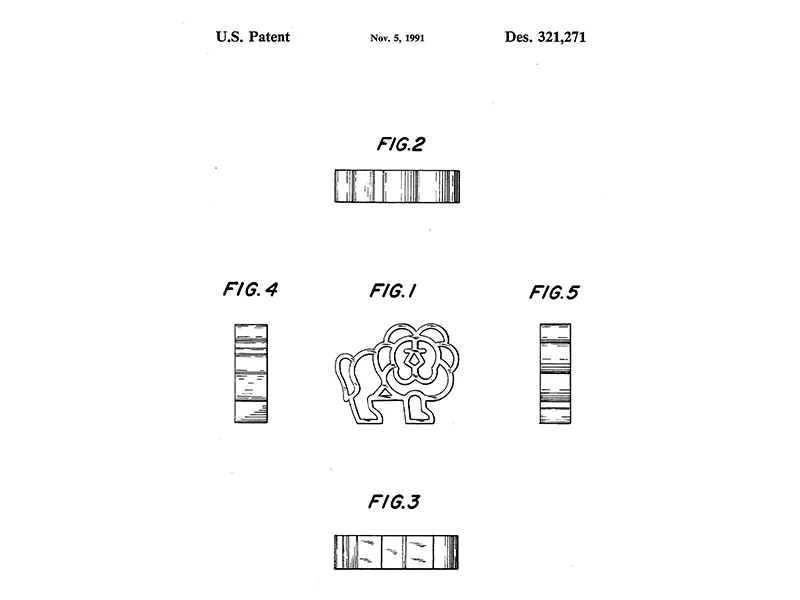

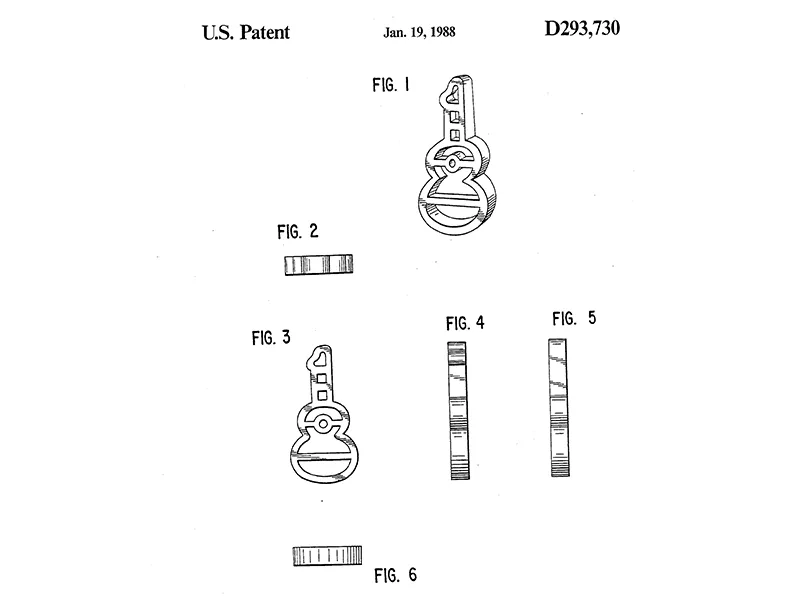

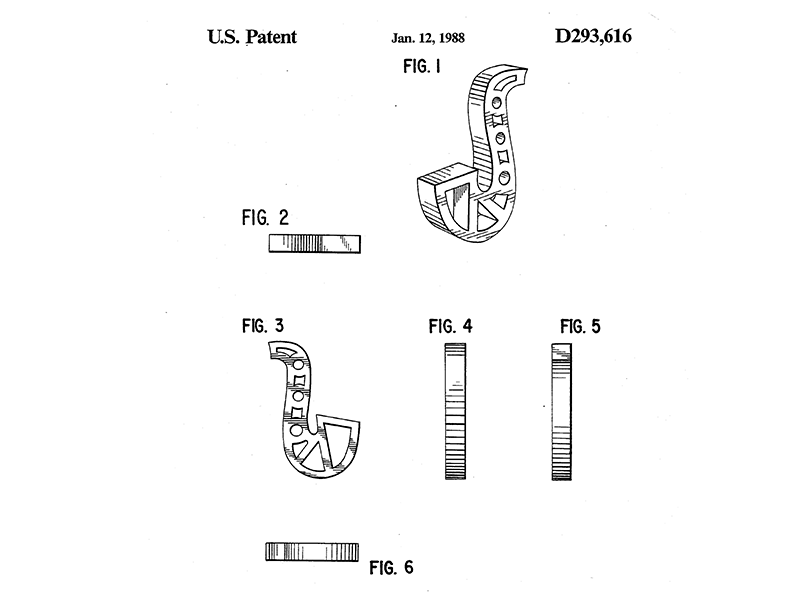

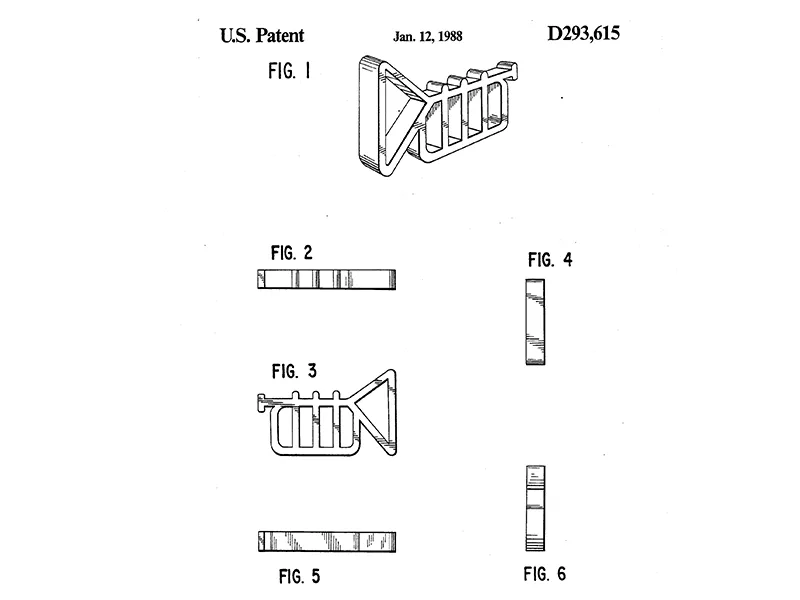

Edward Meyers, Jr., working at CPC foods, now part of Unilever, which makes Knorr products like “Pasta Sides,” was prolific in making imaginative pasta shapes for which he was awarded numerous design patents. Take a look at these patents – a safari of animal-shaped pasta in your dish. Meyers created designs that could take a child’s imagination from the classic elbow pasta shape to a bowl full of elephants, giraffes, rhinoceros and lions (oh my!).

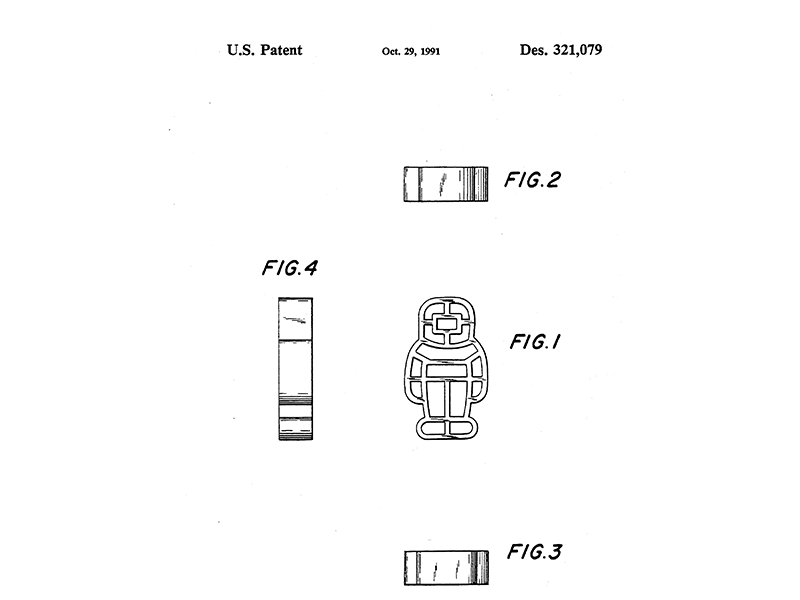

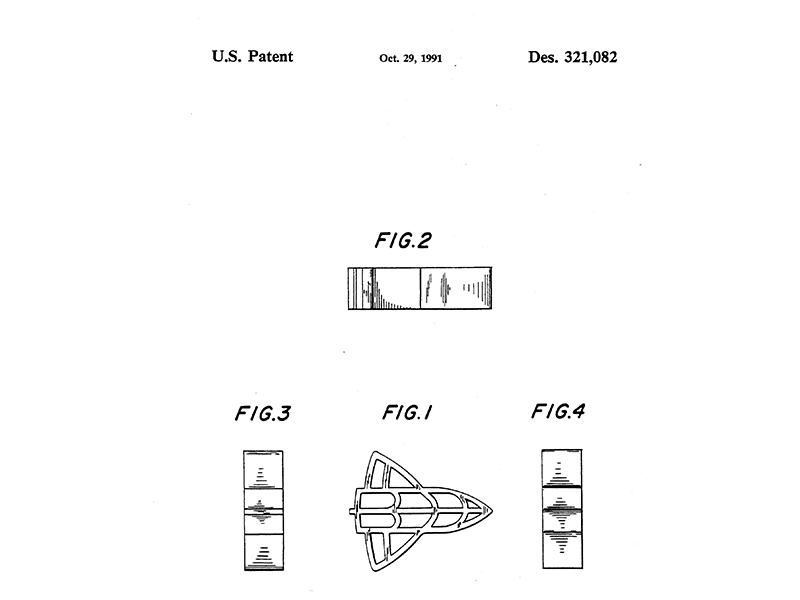

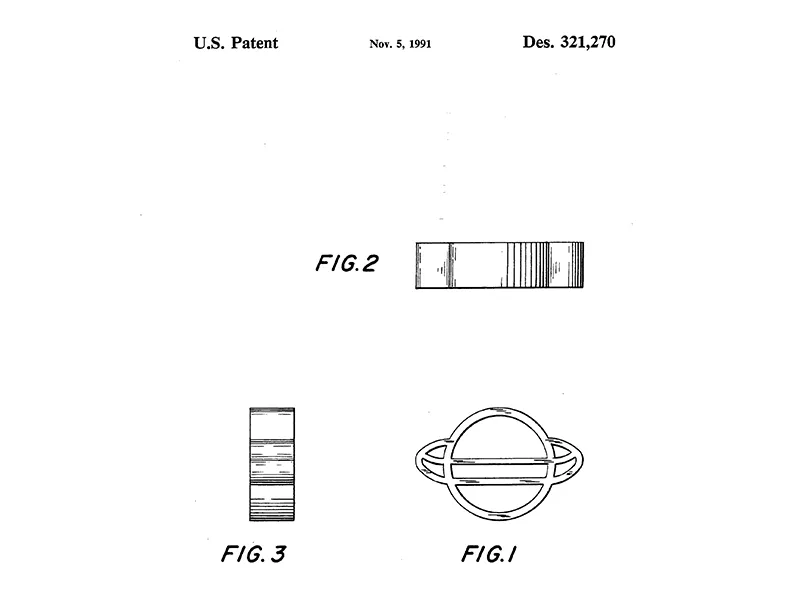

Pasta shapes resembling animals are one thing, and replicating shapes of astronauts and space quite another! This year marks the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, on July 20, and, 28 years ago, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office granted three design patents to Meyers for space-related pasta—in the shape of an astronaut, a spaceship and planet Saturn.

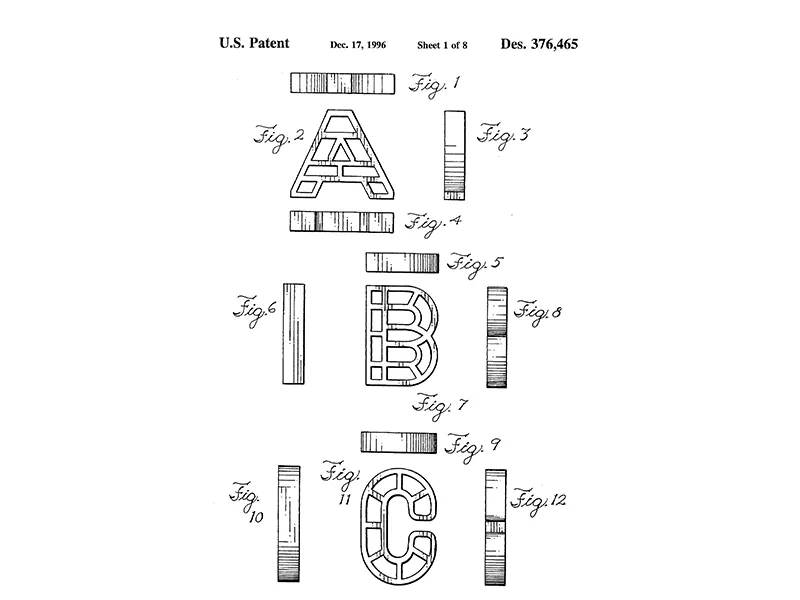

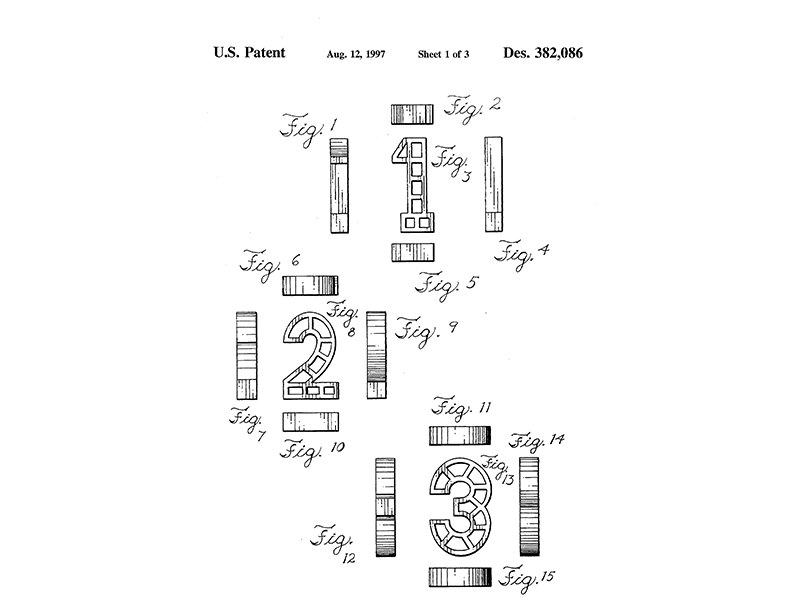

In case safari animals and space are not your style, what about some game-themed mac and cheese for the Super Bowl? In 2013, inventors Ricardo Villota and Guillemo Haro and assignee Kraft, Inc., received design patents for pasta in the shapes of helmets, goal posts, and footballs. In total, Kraft has received 22 design patents for pasta shapes—everything from musical instruments to the alphabet.

High Design

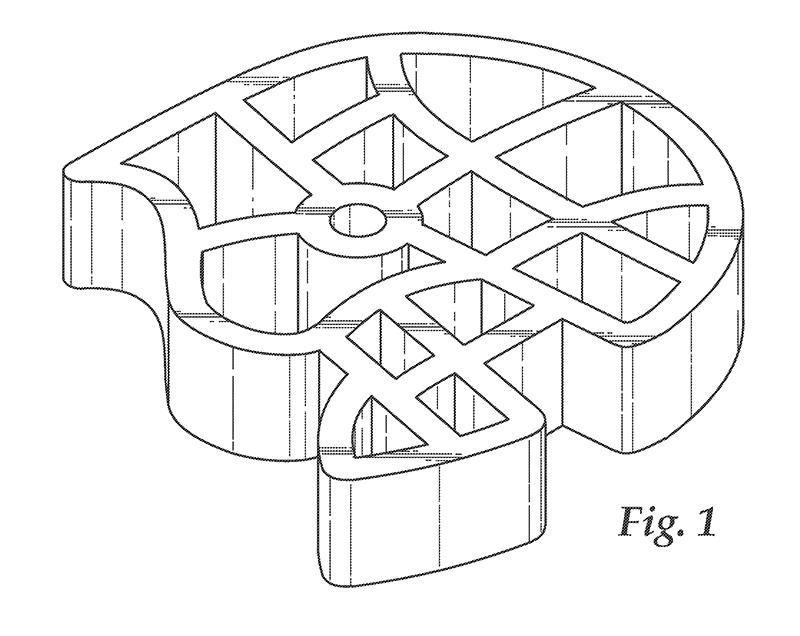

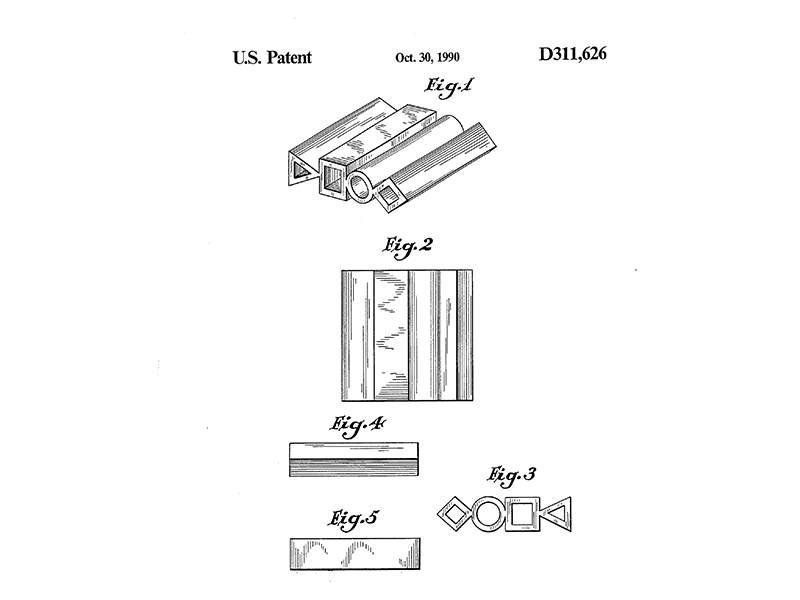

Interesting pasta shapes can also be high design for the chicest of restaurants and gourmands. Architect and designer Phillippe Starck, better known for iconic items like the ghost chair, also designed and patented pasta shapes. According to Starck’s belief, “design is first and foremost a tool that, at best, tries to help people improve their lives.” When Starck was commissioned to create a new innovative pasta design for the Panzani brand, he had several goals in mind: create a health-conscious pasta shape that is 10 percent pasta and 90 percent air, add wings to the pasta for double thickness in case people overcook the pasta, and create a spring-like shape that is well-balanced like yin-yang.

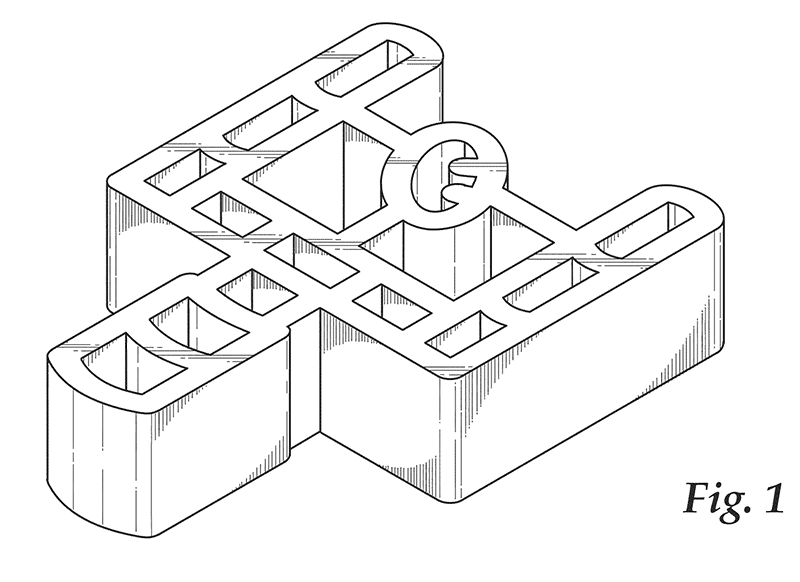

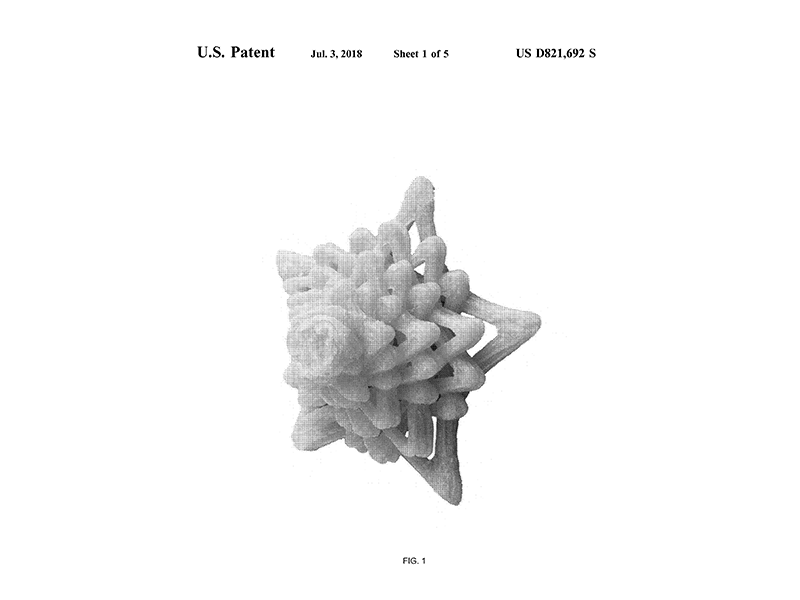

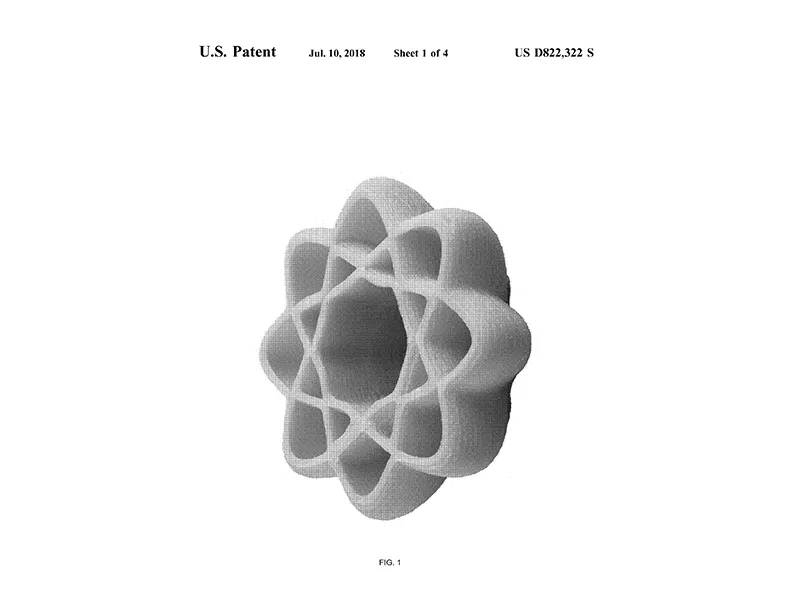

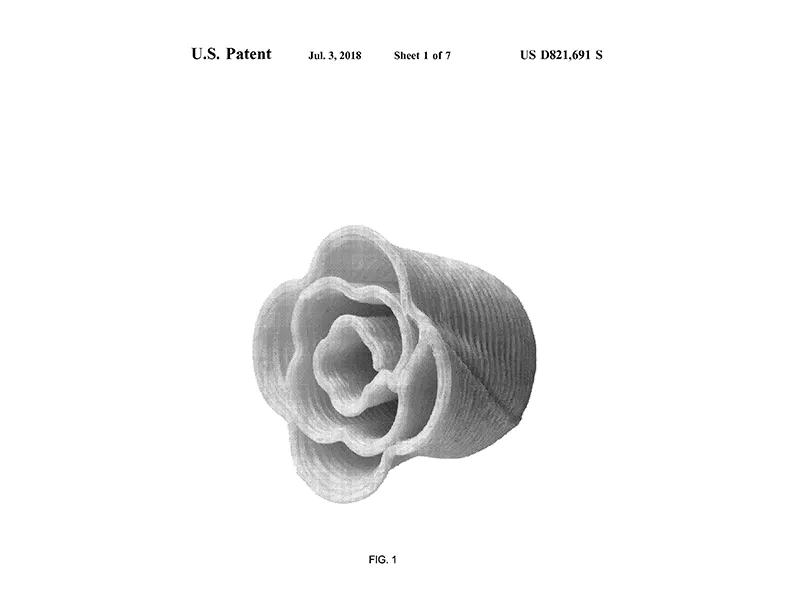

And a Little Bit of 3-D Printing

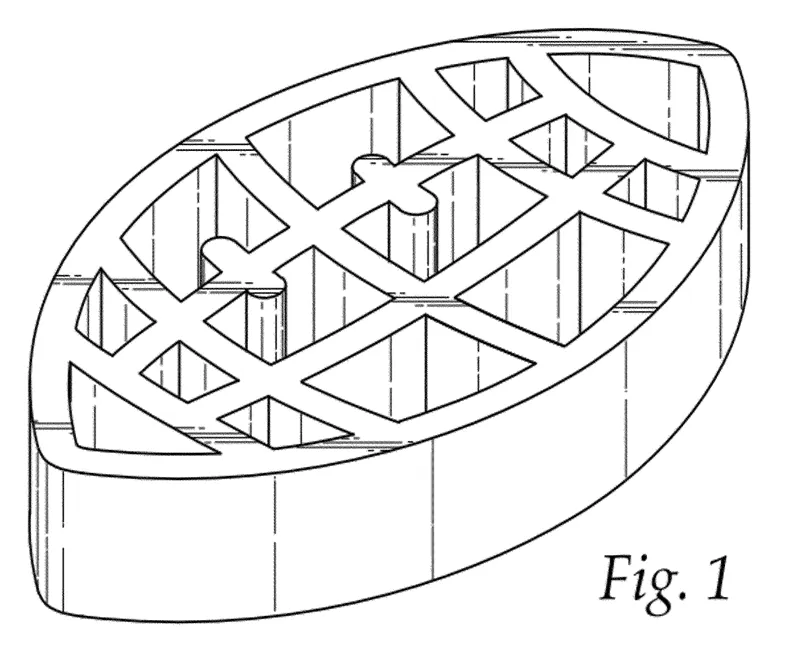

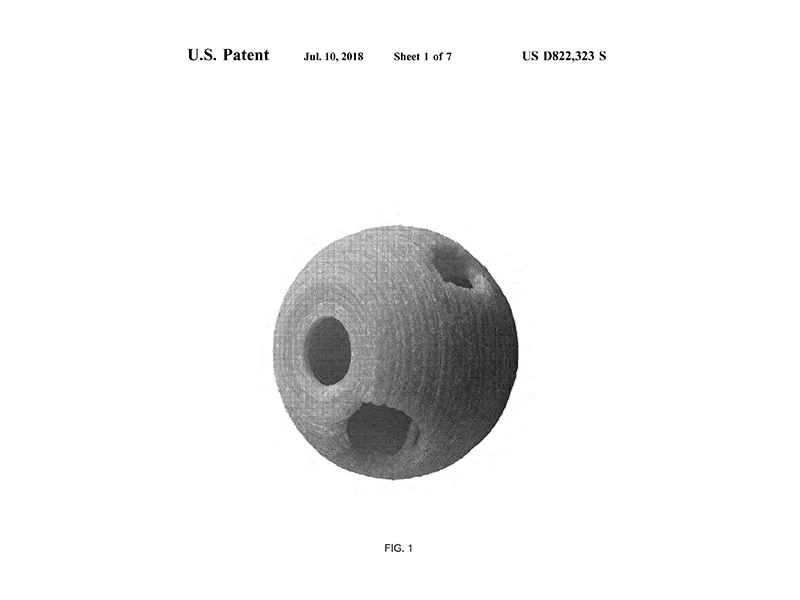

The only limitations when it comes to fanciful pasta shapes seem to be the imagination of the designer and the equipment needed to fabricate them. And what better technology to have for elaborate pasta shapes than 3D printing? Pasta Company Barilla® was the first to introduce this concept in 2014 when they hosted a contest for a 3D printable pasta shape. U.S. design patents nos. 821,691, shaped like a rose, and 822,323, shaped like a ball, were both winners of Barilla’s Print Eat contest. Neither made it to market, but it was a great way for Barilla to demonstrate their 3D printing pasta machine. Since that first project, the company continues to experiment and create pasta shapes that cannot be made by traditional methods. Barilla has design patents for pastas that look like layered stars and flowers. Although technology has advanced enough to change the shape of pasta dramatically, the company treats 3D printed pasta as a specialty application instead of as a replacement to traditional pasta. Barilla-backed BlueRhapsody is now making these products available to the market.

Each of us, no doubt, has our preference, but whichever pasta shape is on your plate, and however it is produced—buon appetito!

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/a8/30a8e9fb-89f9-464a-8ce4-d75b198f12e4/pasta_shapes.jpg)