Before the age of pumpkin spice everything, there was pumpkin pie.

The first English settlers brought the concept of pie to the American colonies. As in their native England, early colonists cooked their pies in long narrow pans called "coffins." The crusts often were not eaten, but simply designed to hold the filling during baking. It was during the American Revolution that the term “crust” replaced “coffin” to describe the pastry shell, and the crust became good enough to eat.

Native to North America, pumpkin was likely served at the first Thanksgiving. However, it is doubtful that it was eaten was in a form that we could consider a pie. Instead, the pumpkin was probably boiled or roasted.

Pumpkin pie did not become a frequent Thanksgiving Day dessert until later. Amelia Simmons included a recipe resembling what we eat today in her American Cookery, the first cookbook by an American published in United States in 1796. This cookbook, which the Library of Congress recently designated one of the 88 “Books That Shaped America,” was quite popular in its day, so the inclusion of the recipe certainly contributed to the popularity of pumpkin pie. Today, about 50 million pumpkin pies are consumed each Thanksgiving.

The traditional pumpkin pie recipe involves a pie pan, a pastry shell and filling. Pie pans are shallow containers, made of virtually any oven-proof material, with sloped sides and a narrow flat rim. The pastry shell is primarily made of flour, fat and water. And the filling contains four key ingredients: pumpkin, a milk product, eggs and sugar, and some optional spices. Once baked, the filling forms a custard.

There are a lot of variations to the crust and filling; everyone has a way of making the pie their own. While you might have a great recipe, it would be very difficult to get a patent today on your pumpkin pie recipe. Typically, recipes of this type are obvious variations of what has been done before; however, there are a host of patented inventions that have helped make it easier to bake a pumpkin pie.

Starting with the pie pan

Many a pumpkin pie starts with a Pyrex glass pie pan. It is not surprising when you think about how Corning has been making glass bakeware since 1915. Corning scientist, Jessie Littleton, enamored with rugged lantern globes and battery jars made of Nonex glass (an early borosilicate glass developed by Eugene Sullivan), thought that it would make an ideal substance for cookware. He knew that a glass pan would absorb heat better than a metal pan, because metal actually reflects most of the heat. To prove his point, Littleton cut off the top of a Nonex glass battery jar and gave the newly created low casserole dish to his wife, Bessie. She found that the glass dish both cooked food faster and cooked at lower temperatures than a metal pan. Glass also had the added benefit that she could see the food as it cooked. The trademark Pyrex®, a fanciful word based on “py” for pie pan (the first product), was first used in 1915, the mark was registered in 1917 (Reg. No. 115,846), and a brand was born. Pyrex ovenware was a great success, selling over four million pieces its first four years of production and an additional 26 million over the following eight years.

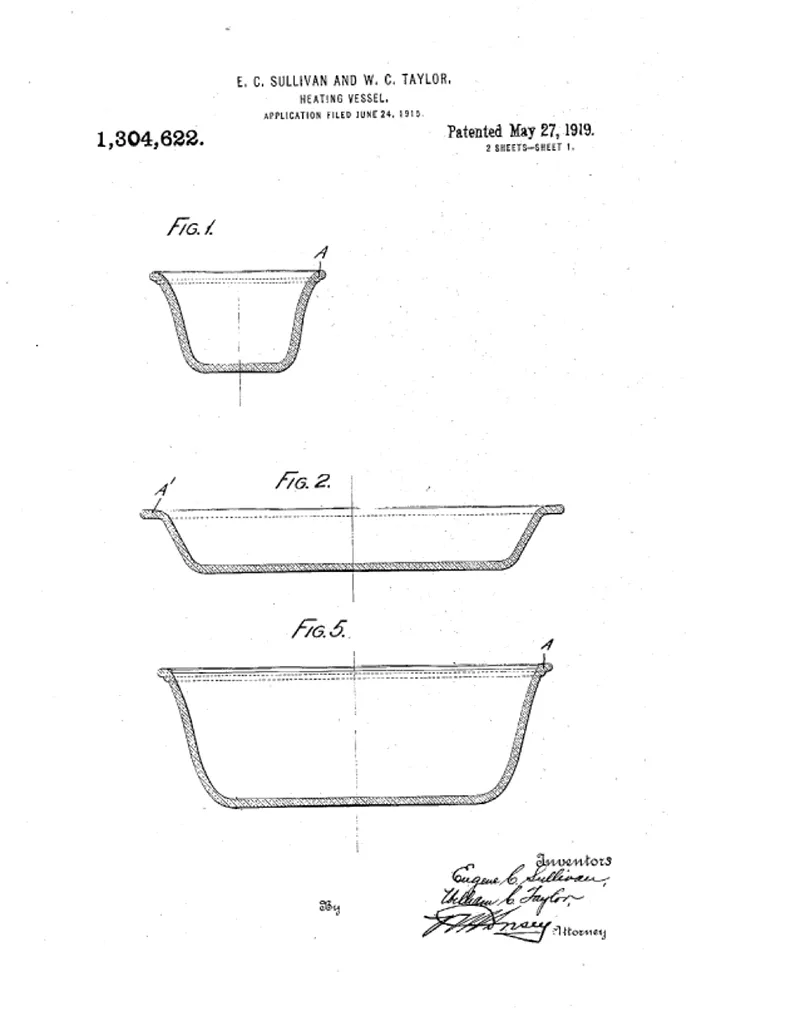

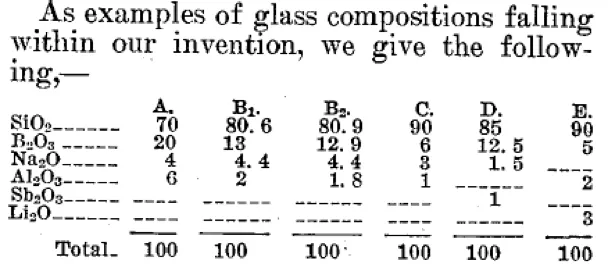

The success of Pyrex ovenware is rooted both in the shape of their baking dishes and in the glass formulation. The Nonex glass was reformulated to remove lead oxide, a common component in glass, and Corning developed a line of baking dishes using the new formulation. Eugene Sullivan and William Taylor of Corning, filed for a patent on both the baking dishes and glass formation on June 24, 1915. The United States Patent Office considered them to be separate inventions. On May 27, 1919, two patents were granted: 1,304,622 to a “heating vessel” and Pat. No. 1,304,623 to the “Glass.”

The pie crust

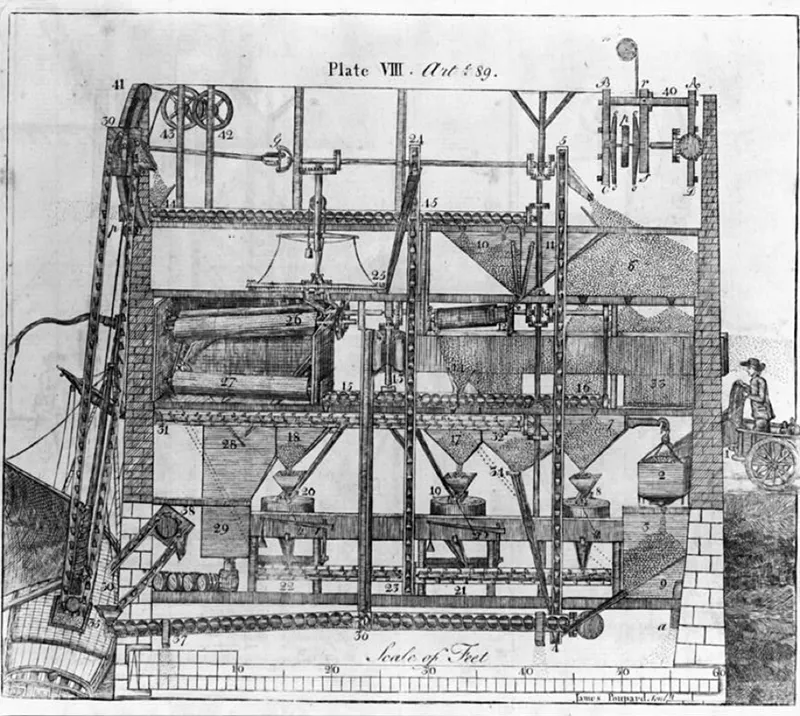

Flour and fat, carefully mixed with just the right amount of water, are the key to making a perfect pie crust. Since colonial times, wheat has been grown in America and gristmills have been turning wheat into flour. George Washington built a gristmill in 1770 and upgraded the mill in 1791 to use patented technology developed by Oliver Evans. Washington learned of Evans's improvements in 1790, when he reviewed and signed the patent application submitted to the newly-established United States Patent Office; it was the third patent granted by the office. Unfortunately, the original patent was lost in the Patent Office fire of 1836 and no longer exists; however, the technology lives on both in books and the gristmill at Mount Vernon. Many patents have been granted on producing flour over the years, but this was the first.

For the second key ingredient in the crust, a hard fat, such as butter, lard or solid vegetable shortening, is carefully cut into the flour leaving small particles of fat covered with flour. Salt is added for flavor, and a little cold water is added to form a dough. There is a science to making pie dough come out flakey. The fat particles need to stay cold enough not to melt so that they can flatten out in the rolling process; moreover, the flour can be easily over worked and gluten can form, making a tough dough. Bakers generally have a preference when it comes to using lard, butter or vegetable shortening.

Solid vegetable shortening originated when Proctor & Gamble was looking for replacements for animal fats in the early 20th century. Edwin Kayser, a German chemist, wrote to the Cincinnati, Ohio-based company on October 18, 1907, about a new chemical process that could create a solid fat from a liquid by hydrogenation. Proctor and Gamble had been looking for a way to convert liquid cotton seed oil, a byproduct of cotton fiber production, into a solid fat that could be used for soap making. They purchased the U.S. rights to Kayser’s patents and began to experiment in turning cotton seed oil into a creamy solid. The material looked very similar to lard, and they began considering this product a replacement for animal fats and marketing it to home cooks. In 1910, John Burchenal of Proctor & Gamble filed a patent application for the “homogenous white or yellowish semi-solid closely simulating lard.” On April 13, 1915, Pat. No. 1,135,351 was granted. One of the objects of the invention was to produce “a shortening in cooking, in which the liability to become rancid is minimized;” the unsaturated bonds in the fats had been removed by hydrogenation so the resulting fats were less likely to become oxidized and go rancid than typical animal fats. The product Crisco® Shortening is the result of this patented technology and came into the market in 1911. The trademark Crisco (Reg. No. 117,704) was first used in commerce in 1911 and registered in 1917. Wrapped in white paper, it was seen as a “pure” economical alternative to animal fats. The product has become a worldwide staple, even being immortalized in sculpture.

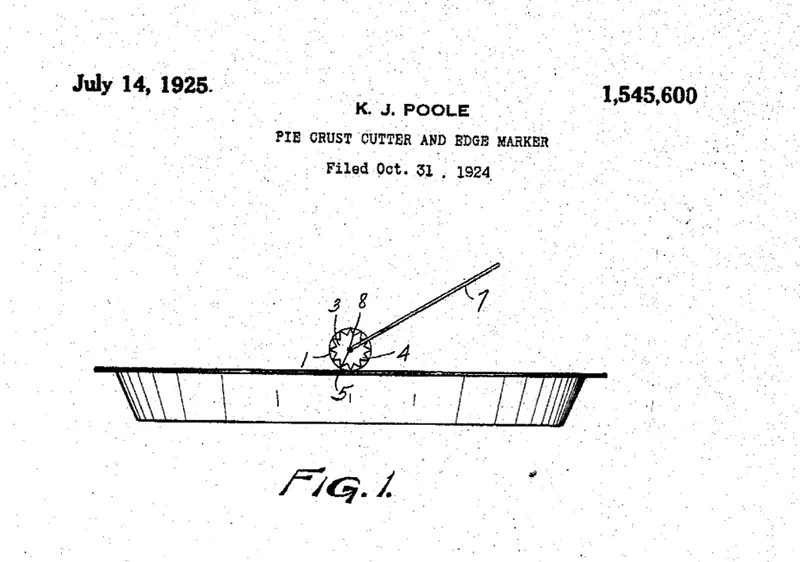

While the pie crust can be mixed by hand and rolled out using a rolling pin, there are a plethora of patents on labor saving devices to help crimp the edge, such as Kenneth James Poole’s Pat. No. 1,545,600 for a “Pie-Crust Cutter and Edge Marker,” granted on July 14, 1925.

Making the filling

The most common recipes call for the use of evaporated milk—the cans of milk that are placed next to the cans of pumpkin on endcaps at the supermarket this time of year. John Meyenberg, of St. Louis, Missouri, received Pat. No. 308,422 on November 25, 1884 for a “Process of Preserving Milk.” The patent describes the process in which the milk is heated and water is “evaporated” and the milk product is “condensed” as the water is removed; hence, the origins of the names “evaporated milk” or “condensed milk.” (Evaporated milk is condensed milk without the added sugar.) The evaporated milk is cooled then sealed in cans, and then heat sterilized. “After this the cans are examined to discover if all are air-tight, and if so they are ready for the market,” the patent reads.

While the pumpkin for the filling can be made by cooking fresh pumpkins and pureeing the flesh, most people used canned pumpkin for convenience, or in some instances taste. Today, 85 percent of the world’s canned pumpkin comes from the Libby Pumpkin Factory in Morton, Illinois. (Libby’s has been selling food products since 1894.) The pumpkins are grown from Libby’s own priority seeds, which yield the desired orange color as well as their non-stringy creamy consistency more akin to a squash than the pumpkins used on Halloween for Jack-o’-lanterns. Peter Durand, a British merchant, is often credited for receiving the first patent (British Pat. No. 3,372) for the idea of preserving food using tin cans on August 25, 1810.

So when you are making and eating your pumpkin pie on Thanksgiving, take a moment to consider all of the patented inventions that have made the perennial favorite what it is today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/3b/1d3b7eb3-2e67-4f2f-9ddd-cfb1149a8e82/pumpkin_pie.jpg)