Juliet so famously pleads to Romeo, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet,” in William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Gertrude Stein, in a 1913 poem, wrote, “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.” As an important image, roses cannot be dismissed.

But have you ever thought of the perennials as an invention?

The United States Patent and Trademark Office grants different types of patents: utility, design and plant. Plant patents specifically cover certain types of asexually reproduced plants, often decorative plants and fruit trees (Think: taking clippings and rooting them vs. starting plants from seeds).

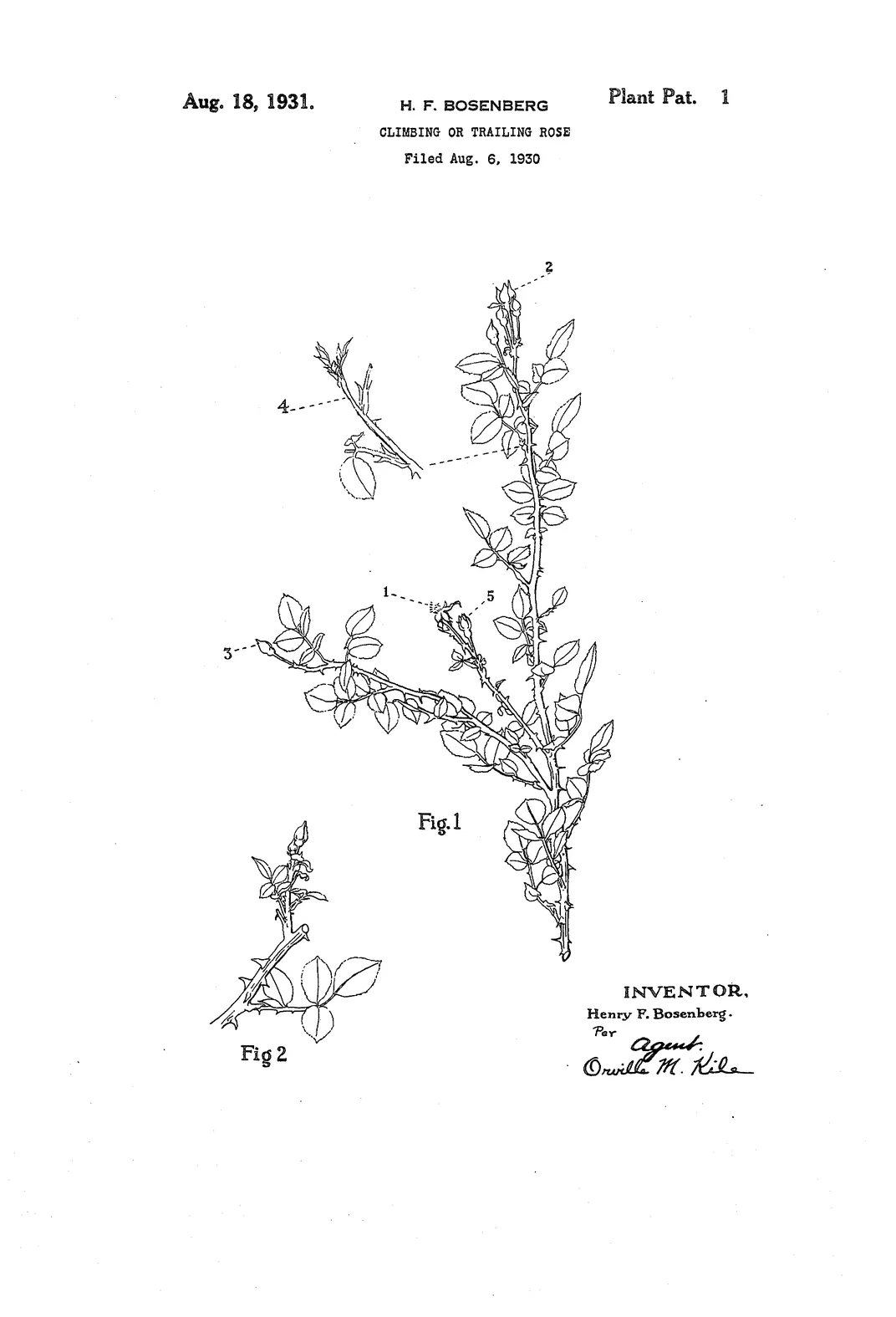

One of the large areas for activity in terms plant patents is roses. In 2016, the USPTO granted 80 plant patents for new and distinct roses, and since the 1930s, the office has issued nearly 6,000 plant patents overall. In fact, U.S. Plant Patent Number 1 was issued to New Jersey resident Henry Bosenberg on August 18, 1931 for "New Dawn," a climbing plant, which bears champagne-colored roses and is “characterized by its everblooming habit.” While the patent protection for the rose variety has long expired, the rose continues to be extremely popular and readily available today.

Another famous patented rose is “Peace,” for which a patent (Plant Pat. 591) was granted on June 15, 1943 to French horticulturist Francis Meillard. Available in the United States since 1945, the rose has graced gardens worldwide and continues to be easily found at garden centers.

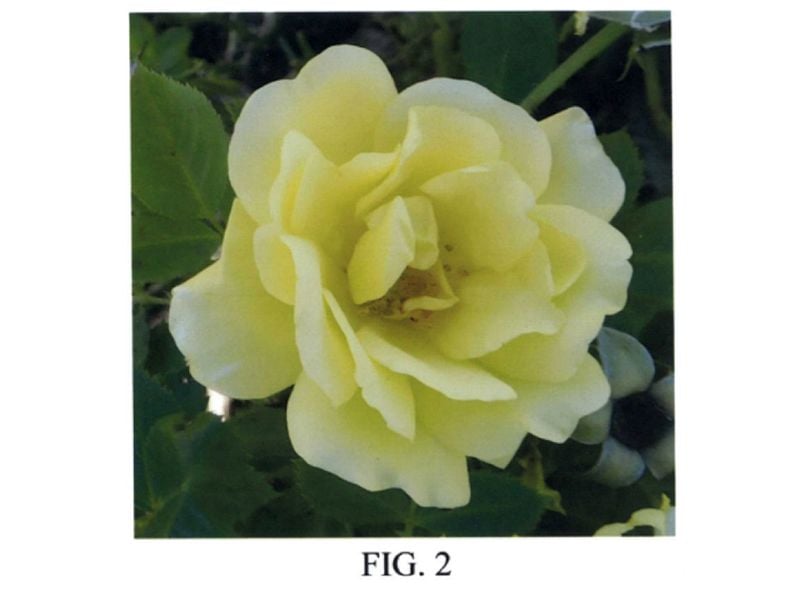

As recently as this past Tuesday, two new rose patents were issued—a plant with orange flowers called “Miniature Rose Plant Named ‘PoupahO70’” (Plant Pat. 27,641) and a bright yellow shrub rose named “Rosa Plant Named SFROSA128” (Plant Pat. 27,640). And more will likely be granted on Valentine’s Day. (New patents are issued every Tuesday.)

Red is the most common rose color given at Valentine’s Day, and long stemmed roses are hybrid tea roses. There have been 708 patented red hybrid tea roses, so there is always a chance that the red roses that you give or receive this Valentine’s Day are patented.

Walter E. Lammerts, for example, was granted a patent (Plant Pat. 2,751) on July 11, 1967, for a red rose plant specifically bred to grow well in green houses. The long-stemmed variety is known to “recycle its blooming quickly during the winter months, as at Christmas and again for Valentine’s Day. “

While not a hybrid tea, the red miniature rose Ralph Moore invented in 1976 (Plant Pat. 3,935), called “My Valentine,” may also fit the bill for the day.

But roses come in other colors too. The color of flowers is predominantly attributed to two types of pigments: flavonoids and carotenoids. Specific flavonoids contribute to pink–red colors and specific carotenoids to yellow-orange colors. Roses can be bred in colors ranging from white to yellow to orange to pink to red, based on the genes that are available in the gene pool of the plant.

Blue pigments do not naturally occur in the gene make up of roses; they lack the delphinidin gene that produces the blue pigment present in other flowers. But there are two ways to make blue roses. One is to take a light colored or white rose, put it in water containing blue pigment, and watch the rose pull the blue pigment up into the plant, including the flower, as transpiration occurs and the plant takes up water. The second is to insert a gene from a plant that makes blue pigment into the genes of a rose plant. This allows the rose plant to express the gene and produce a blue colored flower. The process of producing blue roses is covered by several patents assigned to Florigene (Pat. No. 5,480,789 issued in 1996 and Pat. No. 6,774,285 issued in 2004).

While the roses placed in blue water, have a truer blue color than the ones produced by genetic manipulation, the genetically modified roses sold by Florigene have an attractive lavender color. Time will tell if biologists can invent a truly blue rose.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/94/af/94afb8b5-2483-49fe-9731-d510e973c4b3/roses.jpg)