In 1753, the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus named the cacao tree, Theobroma cacao. “Theos” means “god” in Greek, and “broma” translates to food, giving the plant that bears cocoa beans, the source of so many delectable treats, a fitting name, “cacao, food of the gods.” Even so, chocolate is elevated to a new height at Valentine’s Day.

Chocolate is the ground seeds of the cacao tree, a plant native to the tropical regions of the Americas and part of pre-Columbian culture and food. The first European taste of chocolate was in the form of a rich and bitter beverage, which was given to the Spanish at their meeting with Montezuma in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1519. The Spanish took the concept back to Europe and added sugar first, and later milk to make it more like the hot chocolate and molded chocolate candy of today.

It takes about 9 pods—or approximately 550 seeds or beans, as they are called—to make one pound of unsweetened chocolate, and a lot of patented innovations to transform it into the product you see on shelves now.

Many of the improvements in chocolate in the 19th century and early 20th century related to improving ways of making it into a beverage. We often think of mocha, or a mixture of coffee and chocolate, as something relatively new; however, inventor Daniel Fobes of Boston was issued U.S. Pat. No. 64,856 on May 21, 1867, for a mixture of coffee and chocolate in the form of cakes or tablets that were to be eaten or mixed with water or milk and used as a beverage. In 1911, Servetus Achor of Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, was granted Pat. No. 982,779 for a “Process of Preparing Emulsified Chocolate.” The product comprises chocolate, along with sugar and milk, in such proportions that when mixed with hot water or milk it produced “a delicious refreshing beverage.”

Of course, as wonderful as a chocolate beverage is, today when we think of Valentine’s Day, it’s a box of chocolate candy that usually comes to mind. The solid chocolate used to make beverages in the 19th century could be eaten as solid, and it was sold in that form, but it was grainy because the nib, or center of a cocoa seed, was present in discernible pieces. It was not until the Swiss chocolate manufacturer and inventor Rodolphe Lindt invented the “conche” in 1879, which would grind the chocolate nib in to very small particles that a product came about with a smooth mouth feel. The device was comprised of a granite roller that went back and forth in a granite trough grinding the chocolate.

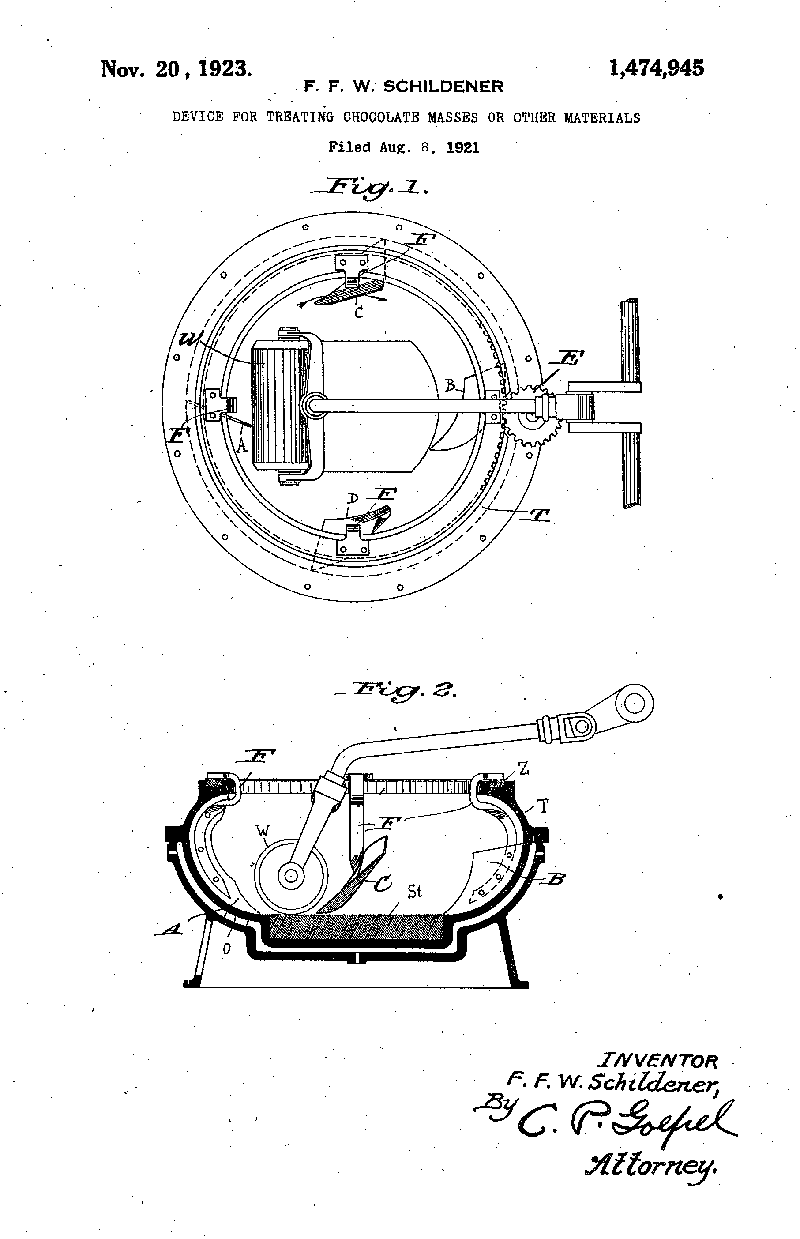

While conches have changed over the years, the continuous grinding of the chocolate over hours and hours remains a constant. German inventor Freidrich Schildener made his own refinement to the conching machine, a “device for treating chocolate masses or other materials” patented in 1923 that combined the roller action developed by Lindt with the attributes of a rotating scraper. The patent discloses how “Untreated raw chocolate is placed in a heated circular container T, in which it is continuously moved to and fro, similar to the mass in a longitudinal grinding mill” and “in order to subject all and any parts of the mass to the treatment a number mixing and scraping blades… rotate around the inner wall of the container."

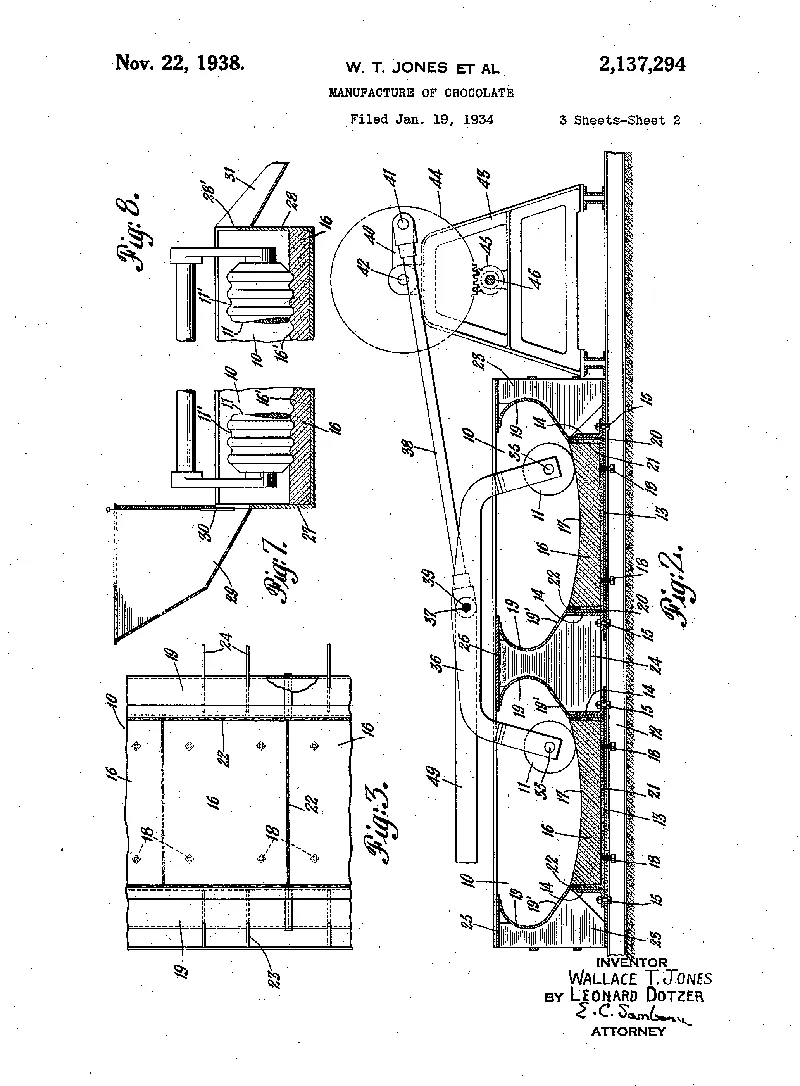

A decade later, Wallace Jones and Leonard Dotzer improved the conching process in yet another way by developing an apparatus and process that used multiple conching rollers and allowed the chocolate to be conched in a continuous stream as opposed to batches.

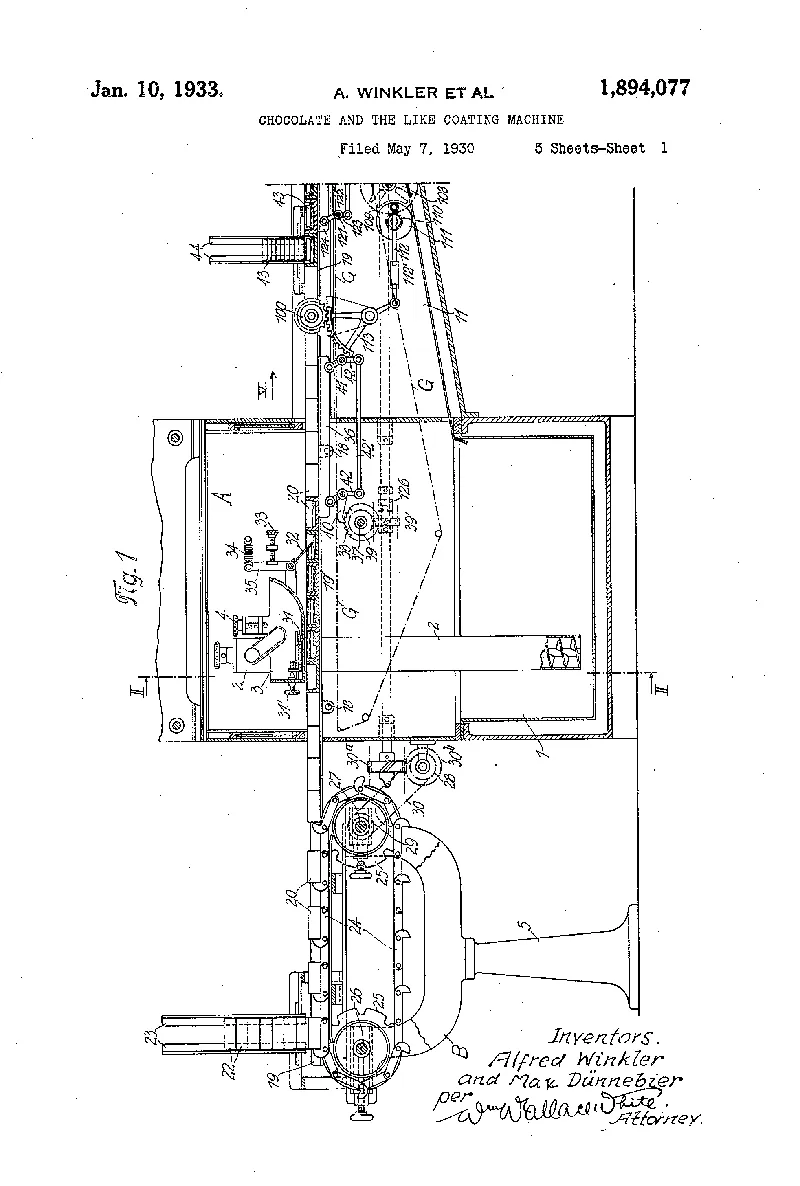

A proper box of Valentine’s Day chocolates comprises a variety of individual chocolate pieces; in the production of individual chocolates, solid pieces need to be molded and fondant or caramel centers need to be coated. This is either done by hand or by using different machines. In the 1930s, Alfred Winkler and Max Dünnebier developed and patented a multipurpose machine for “coating sugar bodies, biscuits and other articles with chocolate and the like.” In 1938, chocolate making was often local business; candy would have to travel by rail, and the melting point of chocolate made it something that was not easy to ship. Small local companies needed flexible machines that could produce a variety chocolates. The machine developed by Winkler and Dünnebier could both coat fondant or caramel centers and mold both solid and hollow chocolates. While large commercial operations today would have separate machines to do these tasks as their scale would allow for the space, capital investment and capacity, a small operation could still use this machine today.

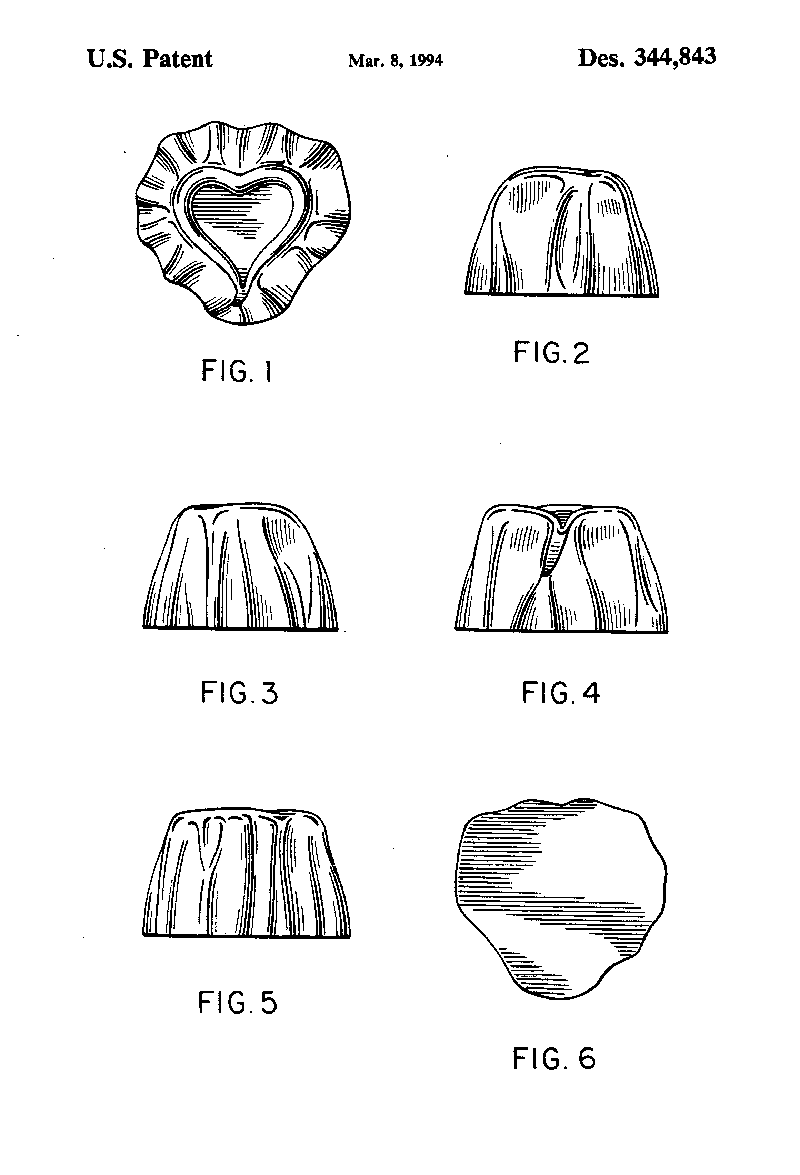

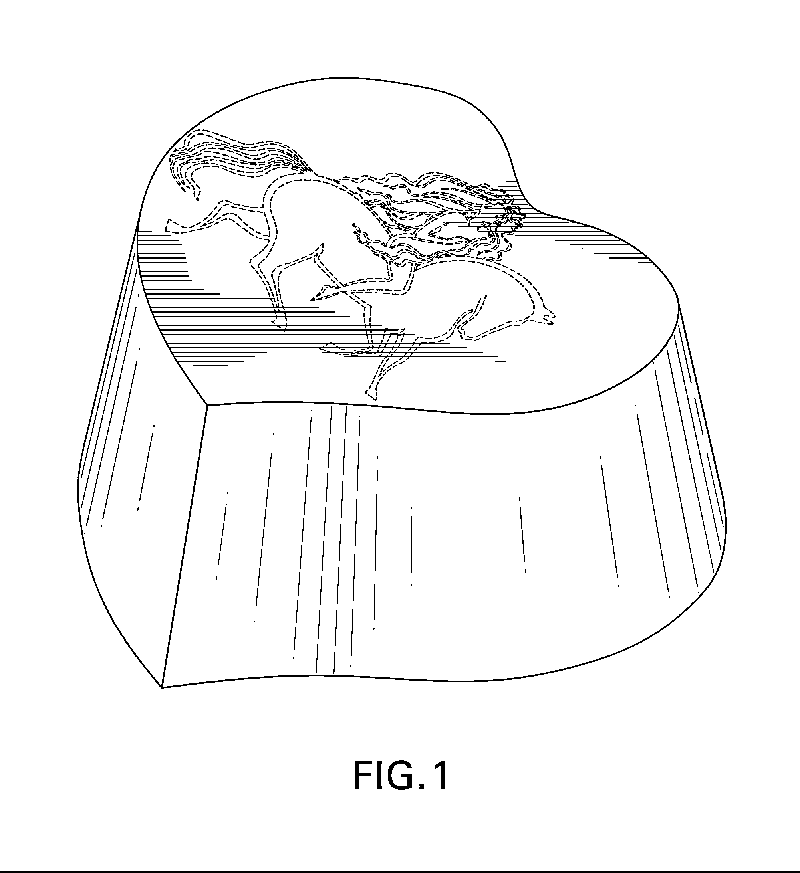

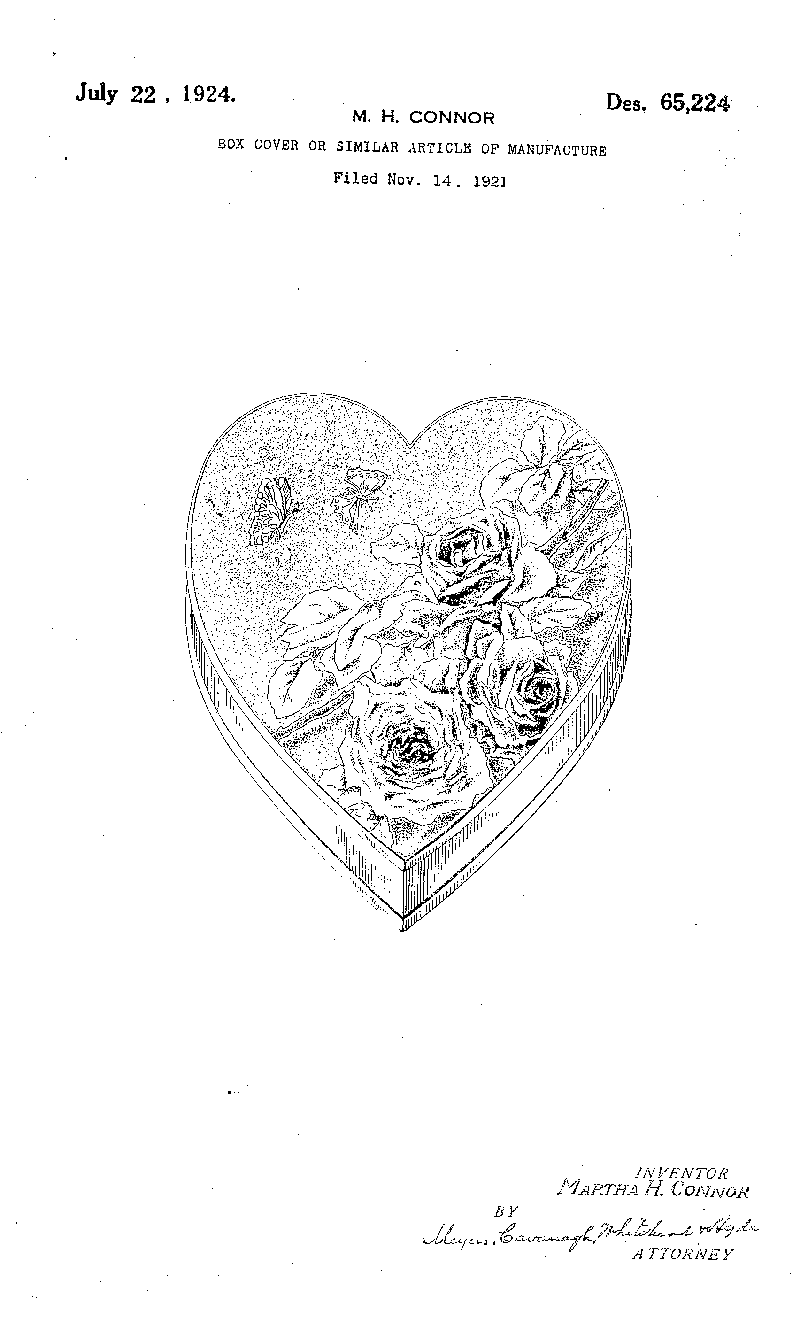

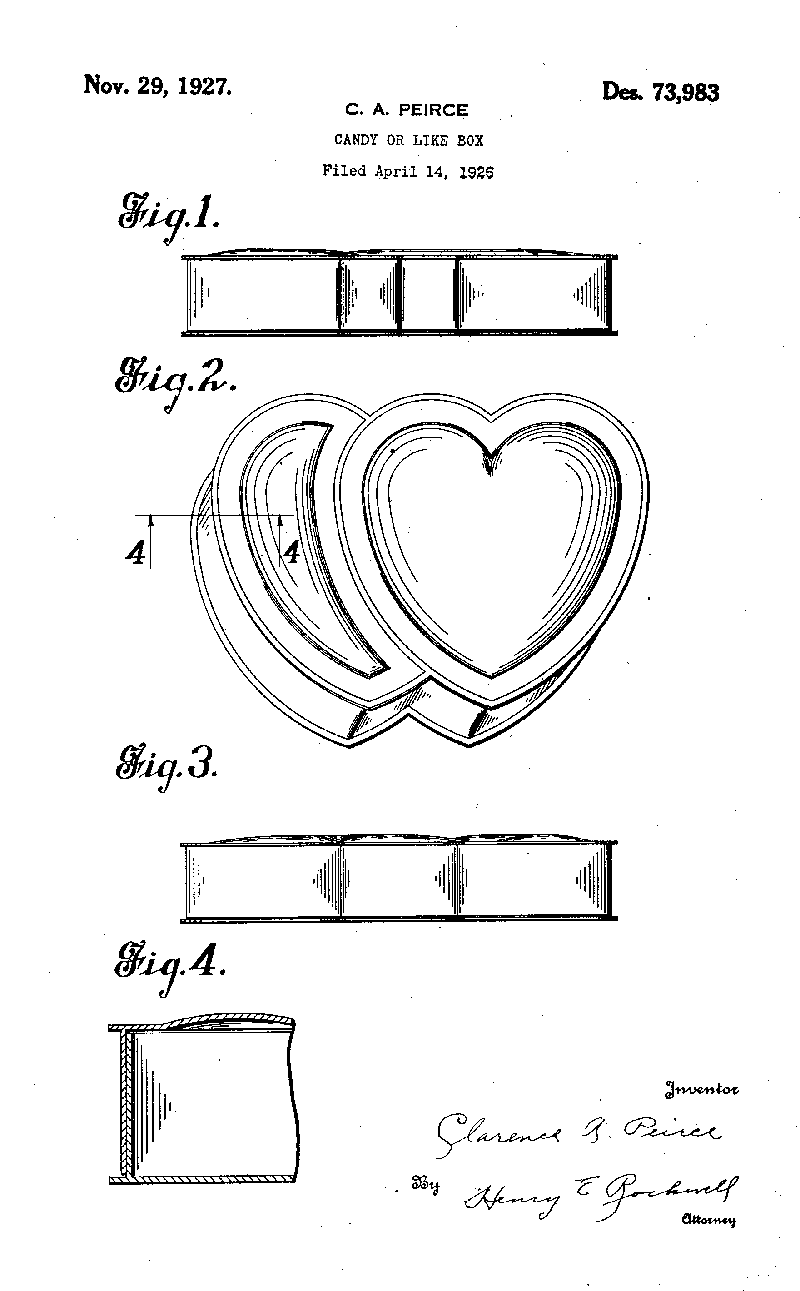

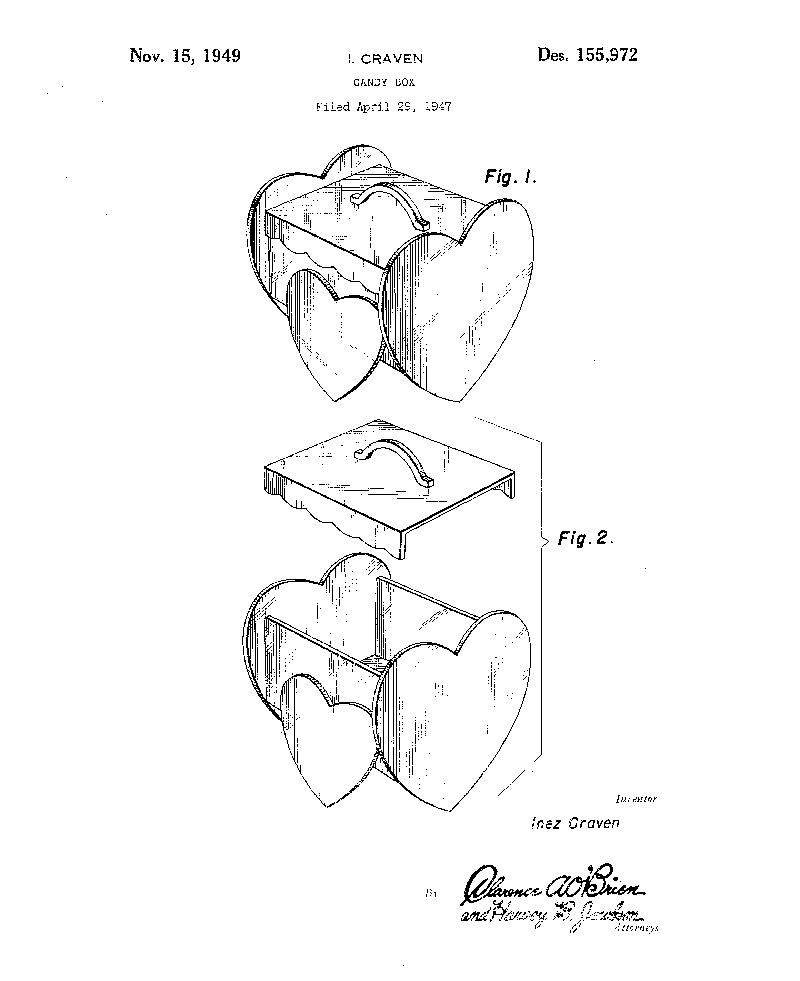

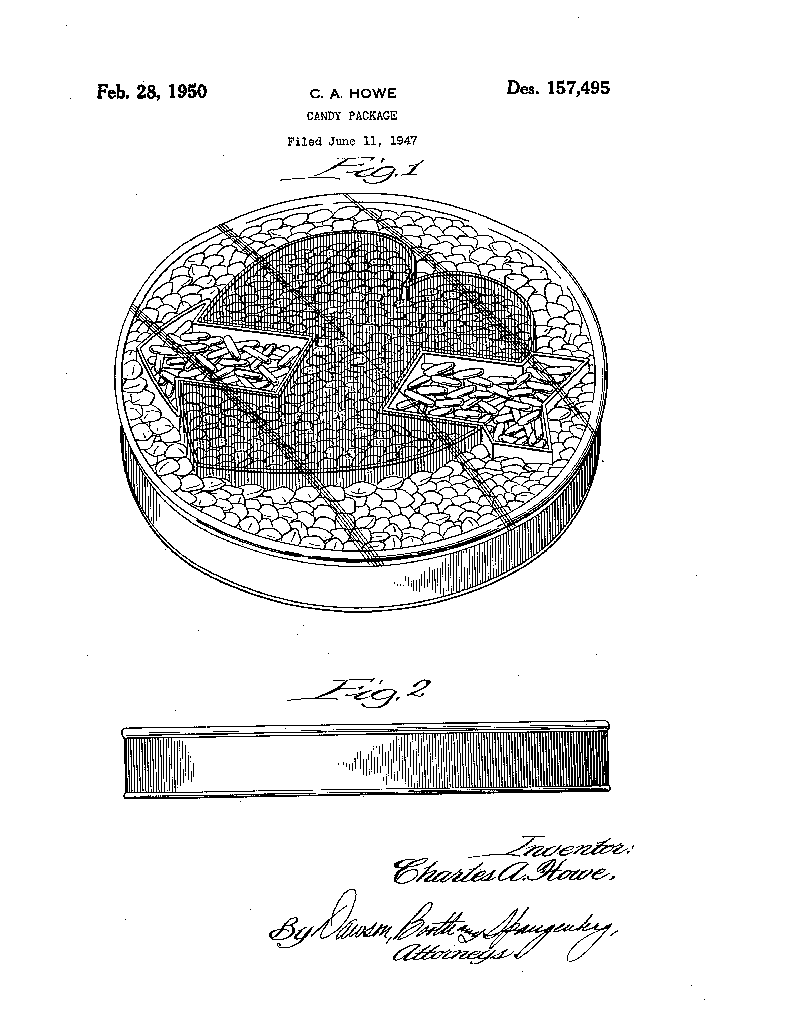

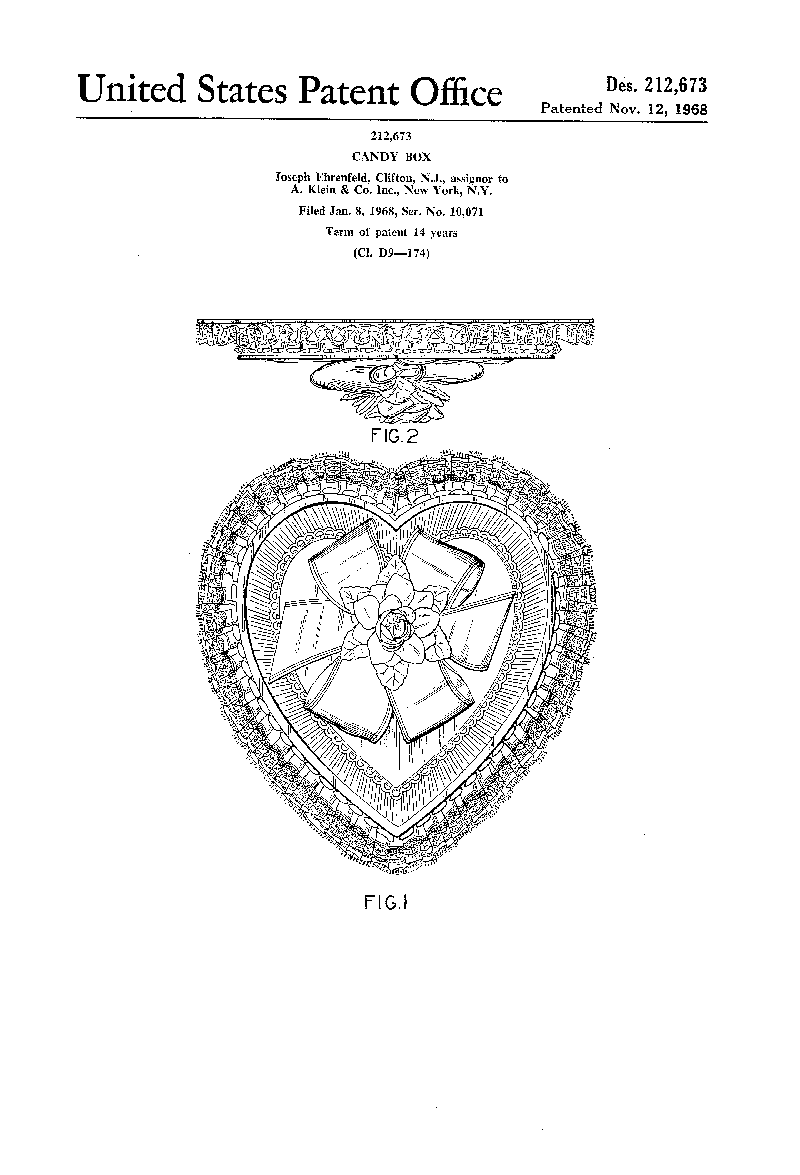

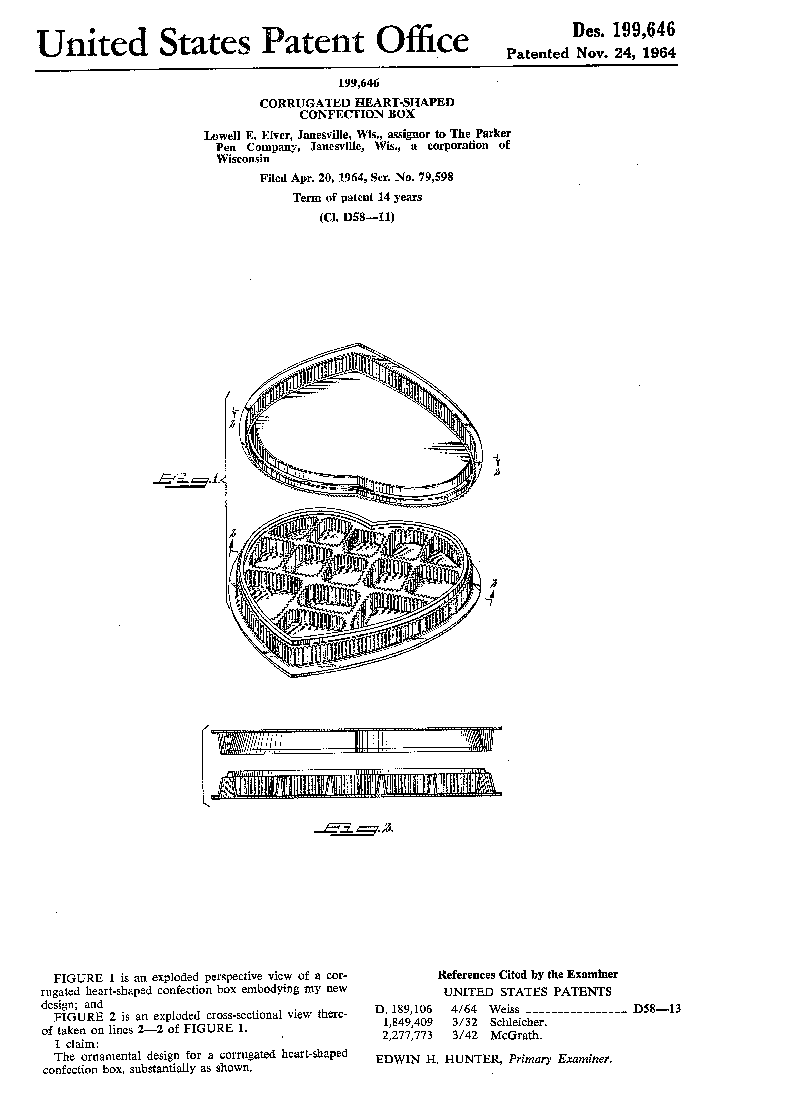

Certainly, when it comes to chocolates for the holiday, presentation is a key element. In 1861, British chocolatier Richard Cadbury put “eating chocolates” in boxes decorated with cupids and rosebuds—a move that is part of an extensive design history in the presentation of chocolates. We’ve grown accustomed to receiving our chocolates, sometimes heart-shaped pieces of Dove or Godiva chocolate, in heart-shaped boxes, many of which have even been patented.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/6a/566ae274-6793-4619-b888-e26c6b6369e5/valentine_chocolate.jpg)