A Monumental Struggle to Preserve Hagia Sophia

In Istanbul, secularists and fundamentalists clash over restoring the nearly 1,500 year-old structure

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fadingglory_dec08_631.jpg)

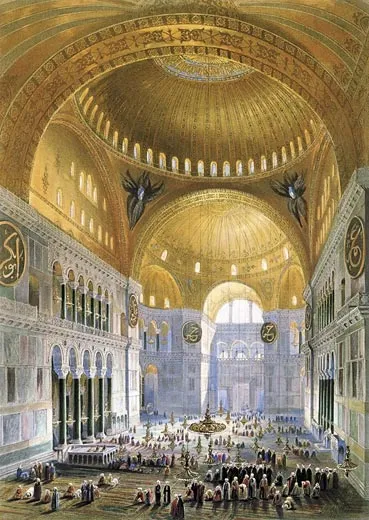

Zeynep Ahunbay led me through the massive cathedral's cavernous nave and shadowy arcades, pointing out its fading splendors. Under the great dome, filtered amber light revealed vaulted arches, galleries and semi-domes, refracted from exquisite mosaics depicting the Virgin Mary and infant Jesus as well as long-vanished patriarchs, emperors and saints. Yet the overall impression was one of dingy neglect and piecemeal repair. I gazed up at patches of moisture and peeling paint; bricked-up windows; marble panels, their incised surfaces obscured under layers of grime; and walls covered in mustard-colored paint applied by restorers after golden mosaics had fallen away. The depressing effect was magnified by a tower of cast-iron scaffolding that cluttered the nave, testament to a lagging, intermittent campaign to stabilize the beleaguered monument.

"For months at a time, you don't see anybody working," said Ahunbay, a professor of architecture at Istanbul Technical University. She had directed a partial restoration of the building's exterior in the late 1990s and is regarded by conservators as its guardian angel. "One year there is a budget, the next year there is none," she said with a sigh. "We need a permanent restoration staff, conservators for the mosaics, frescoes and masonry, and we need to have them continuously at work."

Greeting her with a deferential salute, a workman beckoned us to accompany him through a massive wooden door, half hidden in shadow beneath an overhead gallery. Following the beam of his flashlight, we made our way across a pitch-dark antechamber and up a steep cobblestone ramp littered with fallen masonry and plaster. The incline may have been built to enable the sixth-century builders to cart construction materials to the second-story gallery. "There are problems here too," said Ahunbay, pointing to jagged cracks in the brick vaulting overhead.

Visible for miles across the Sea of Marmara, Istanbul's Hagia Sophia, with its giant buttresses and soaring minarets, symbolizes a cultural collision of epic proportions. (The name translates from the Greek as "Sacred Wisdom.") The structure stands not only as a magnificent architectural treasure but also as a complex accretion of myth, symbol and history. The landmark entwines the legacies of medieval Christianity, the Ottoman Empire, resurgent Islam and modern secular Turkey in a kind of Gordian knot, confounding preservationists who want to save it from decay and restore its former glory.

In addition to the obvious challenges—leaks, cracks and neglect—an invisible menace may pose an even greater danger. Istanbul sits squarely atop a geologic fault line. "There most definitely are seismic threats to Hagia Sophia, and they are great," says Stephen J. Kelley, a Chicago-based architect and engineer who consults on Byzantine churches in Turkey, the former Soviet Union and the Balkans. "One tremor and the whole thing could come falling down."

"Conservationists are very concerned about Hagia Sophia," says John Stubbs, a vice president of the New York-based World Monuments Fund, which contributed $500,000 and raised another half million in matching funds for urgent repairs during the last decade."It's an unbelievably complex structure. There's the roof, the stonework, marble, mosaics, paintings. We don't even know all that's in play in there. But we do know that it requires ongoing, vigilant attention. Hagia Sophia is an utterly unique building—a key monument in the history of architecture and a key symbol of the city of Constantinople right through to our time."

Constantinople, as Istanbul was known for centuries, owed its importance to the Emperor Constantine, who made it the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire in A.D. 330. Although an earlier basilica of the same name once stood on the site, today's Hagia Sophia was a creation of the Emperor Justinian, who rose from humble origins to become the greatest of the early rulers of the empire that historians would call Byzantium. During his 38-year reign, from 527 to 565, Justinian labored to bring harmony to the disputatious factions of the Eastern Orthodox Church; organized Roman law into a code that would influence European legal systems down to the present; and set his armies on the march, enlarging the empire until it reached from the Black Sea to Spain. He also erected hundreds of new churches, libraries and public edifices throughout the empire. Hagia Sophia, completed in 537, was his crowning architectural achievement. Until the 15th century, no building incorporated a floor space so vast under one roof. Four acres of golden glass cubes—millions of them—studded the interior to form a glittering canopy overhead, each one set at a subtly different angle to reflect the flicker of candles and oil lamps that illuminated nocturnal ceremonies. Forty thousand pounds of silver encrusted the sanctuary. Columns of purple porphyry and green marble were crowned by capitals so intricately carved that they seemed as fragile as lace. Blocks of marble, imported from as far away as Egypt and Italy, were cut into decorative panels that covered the walls, making the church's entire vast interior appear to swirl and dissolve before one's eyes. And then there is the astonishing dome, curving 110 feet from east to west, soaring 180 feet above the marble floor. The sixth-century historian Procopius marveled that it "does not appear to rest upon a solid foundation, but to cover the place beneath as though it were suspended from heaven by the fabled golden chain."

Magnificent as it was, Hagia Sophia contained none of its splendid figurative mosaics at first. Justinian may have acceded to the wishes of his wife, Theodora (who reputedly began her career as an entertainer and prostitute), and others who opposed the veneration of human images—later to become known as "iconoclasts." By the ninth century, those who worshiped such images, the "iconodules," gained ascendancy, commissioning artists to make up for lost time. Medieval pilgrims were awed by the mosaics, ranging from depictions of stylized angels to emperors and empresses, as well as a representation of an all-seeing Christ looming from the dome. Many of these images are lost; those few that remain are unique, says art historian Natalia Teteriatnikov, former curator at Dumbarton Oaks, in Washington, D.C., where a center for Byzantine studies is housed. "They cover almost the entire history of Byzantium, from 537 through the restoration of the icons and on up to imperial portraits from the late 14th century. No other Byzantine monument covers such a span of time."

For more than 900 years, Hagia Sophia was the most important building in the Eastern Christian world: the seat of the Orthodox patriarch, counterpart to Roman Catholicism's pope, as well as the central church of the Byzantine emperors, whose palace stood nearby. "Hagia Sophia summed up everything that was the Orthodox religion," says Roger Crowley, author of 1453: The Holy War for Constantinople and the Clash of Islam and the West. "For Greeks, it symbolized the center of their world. Its very structure was a microcosm of heaven, a metaphor for the divine mysteries of Orthodox Christianity." Pilgrims came from across the Eastern Christian world to view its icons, believed to work miracles, and an unmatched collection of sacred relics. Within the cathedral's holdings were artifacts alleged to include pieces of the True Cross; the lance that pierced Christ's side; the ram's horns with which Joshua blew down the walls of Jericho; the olive branch carried by the dove to Noah's ark after the Flood; Christ's tunic; the crown of thorns; and Christ's own blood. "Hagia Sophia," says Crowley, "was the mother church—it symbolized the everlastingness of Constantinople and the Empire."

In the 11th century, the Byzantines suffered the first in a series of devastating defeats at the hands of Turkish armies, who surged westward across Anatolia, steadily whittling away at the empire. The realm was further weakened in 1204 when western European crusaders en route to the Holy Land, overtaken by greed, captured and looted Constantinople. The city never fully recovered.

By the mid-15th century, Constantinople was hemmed in by Ottoman-controlled territories. On May 29, 1453, after a seven-week siege, the Turks launched a final assault. Bursting through the city's defenses and overwhelming its outnumbered defenders, the invaders poured into the streets, sacking churches and palaces, and cutting down anyone who stood in their way. Terrified citizens flocked to Hagia Sophia, hoping that its sacred precincts would protect them, praying desperately that, as an ancient prophesied, an avenging angel would hurtle down to smite the invaders before they reached the great church.

Instead, the sultan's janissaries battered through the great wood-and-bronze doors, bloody swords in hand, bringing an end to an empire that had endured for 1,123 years. "The scene must have been horrific, like the Devil entering heaven," says Crowley. "The church was meant to embody heaven on earth, and here were these aliens in turbans and robes, smashing tombs, scattering bones, hacking up icons for their golden frames. Imagine appalling mayhem, screaming wives being ripped from the arms of their husbands, children torn from parents, and then chained and sold into slavery. For the Byzantines, it was the end of the world." Memory of the catastrophe haunted the Greeks for centuries. Many clung to the legend that the priests who were performing services that day had disappeared into Hagia Sophia's walls and would someday reappear, restored to life in a reborn Greek empire.

That same afternoon, Constantinople's new overlord, Sultan Mehmet II, rode triumphantly to the shattered doors of Hagia Sophia. Mehmet was one of the great figures of his age. As ruthless as he was cultivated, the 21-year-old conqueror spoke at least four languages, including Greek, Turkish, Persian and Arabic, as well as some Latin. He was an admirer of European culture and patronized Italian artists, such as the Venetian master Gentile Bellini, who painted him as a bearded, introspective figure swathed in an enormous robe, his small eyes gazing reflectively over an aristocratically arched nose. "He was ambitious, superstitious, very cruel, very intelligent, paranoid and obsessed with world domination," says Crowley. "His role models were Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar. He saw himself as coming not to destroy the empire, but to become the new Roman emperor." Later, he would cast medallions that proclaimed him, in Latin, "Imperator Mundi"—"Emperor of the World."

Before entering the church, Mehmet bent down to scoop up a fistful of earth, pouring it over his head to symbolize his abasement before God. Hagia Sophia was the physical embodiment of imperial power: now it was his. He declared that it was to be protected and was immediately to become a mosque. Calling for an imam to recite the call to prayer, he strode through the handful of terrified Greeks who had not already been carted off to slavery, offering mercy to some. Mehmet then climbed onto the altar and bowed down to pray.

Among Christians elsewhere, reports that Byzantium had fallen sparked widespread anxiety that Europe would be overrun by a wave of militant Islam. "It was a 9/11 moment," says Crowley. "People wept in the streets of Rome. There was mass panic. People long afterward remembered exactly where they were when they heard the news." The "terrible Turk," a slur popularized in diatribes disseminated across Europe by the newly invented printing press, soon became a synonym for savagery.

In fact, the Turks treated Hagia Sophia with honor. In contrast to other churches that had been seized and converted into mosques, the conquerors refrained from changing its name, merely adapting it to the Turkish spelling. ("Ayasofya" is the way it is written in Turkey today.) Mehmet, says Ilber Ortayli, director of the Topkapi Palace Museum, the former residence of the Ottoman emperors, "was a man of the Renaissance, an intellectual. He was not a fanatic. He recognized Hagia Sophia's greatness and he saved it."

Remarkably, the sultan allowed several of the finest Christian mosaics to remain, including the Virgin Mary and images of the seraphs, which he considered to be guardian spirits of the city. Under subsequent regimes, however, more orthodox sultans would be less tolerant. Eventually, all of the figurative mosaics were plastered over. Where Christ's visage had once gazed out from the dome, Koranic verses in Arabic proclaimed: "In the name of God the merciful and pitiful, God is the light of heaven and earth."

Until 1934, Muslim calls to prayer resounded from Hagia Sophia's four minarets—added after Mehmet's conquest. In that year, Turkey's first president, Kemal Ataturk, secularized Hagia Sophia as part of his revolutionary campaign to westernize Turkey. An agnostic, Ataturk ordered Islamic madrassas (religious schools) closed; banned the veil; and gave women the vote—making Turkey the first Muslim country to do so. He cracked down harshly on once-powerful religious orders. "Fellow countrymen," he warned, "you must realize that the Turkish Republic cannot be the country of sheikhs or dervishes. If we want to be men, we must carry out the dictates of civilization. We draw our strength from civilization, scholarship and science and are guided by them. We do not accept anything else." Of Hagia Sophia he declared: "This should be a monument for all civilization." It thus became the world's first mosque to be turned into a museum. Says Ortayli, "At the time, this was an act of radical humanism."

Although ethnic Greeks constituted a sizable proportion of Istanbul's population well into the 20th century, the heritage of Byzantium was virtually expunged from history, first by Mehmet's Ottoman successors, then by a secular Turkey trying to foster Turkish nationalism. Nobel Prize- winning author Orhan Pamuk says that by the 1960s, Hagia Sophia had become a remnant of an unimaginably distant age. "As for the Byzantines," he writes in his memoir, Istanbul, "they had vanished into thin air soon after the conquest, or so I'd been led to believe. No one had told me that it was their grandchildren's grandchildren's grandchildren who now ran the shoe stores, patisseries, and haberdasheries of Beyoglu," a center-city neigborhood.

Turkish authorities have made little effort to excavate and protect the vestiges of Byzantium (apart from Hagia Sophia and a handful of other sites) that lie buried beneath modern Istanbul. The city's growth from a population of 1 million in the 1950s to 12 million today has created development pressures that preservationists are ill equipped to resist. Robert Ousterhout, an architectural historian at the University of Pennsylvania, has worked on Byzantine sites in Turkey since the 1980s; he was once awakened in the middle of the night by work crews surreptitiously demolishing a sixth-century Byzantine wall behind his house to make room for a new parking lot. "This is happening all over old Istanbul," says Ousterhout. "There are laws, but there's no enforcement. Byzantine Istanbul is literally disappearing day by day and month by month."

Hagia Sophia, of course, is in no danger of being knocked down in the middle of the night. It is almost universally regarded as the nation's "Taj Mahal," as one conservator put it. But the monument's fate remains hostage to the roiling political and religious currents of present-day Turkey. "The building has always been treated in a symbolic way—by Christians, Muslims, and by Ataturk and his secular followers," says Ousterhout. "Each group looks at Hagia Sophia and sees a totally different building." Under Turkish laws dating from the 1930s, public prayer is prohibited in the museum. Nevertheless, religious extremists are bent on reclaiming it for their respective faiths, while other Turks remain equally determined to retain it as a national symbol of a proud—and secular—civilization.

Hagia Sophia has also become a potent symbol for Greeks and Greek-Americans. In June 2007, Chris Spirou, president of the Free Agia Sophia Council of America, a U.S.-based advocacy group whose Web site features photographs depicting the building with its minarets erased, testified in Washington, D. C. at hearings sponsored by the Congressional Human Rights Caucus that the one-time cathedral had been "taken prisoner" by the Turks; he called for it to be restored as the "Holy House of Prayer for all Christians of the world and the Basilica of Orthodoxy that it was before the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks." Spirou then asserted, in terms usually reserved for the world's outlaw regimes, that "Hagia Sophia stands as the greatest testimony to the ruthlessness, the insensitivity and the barbaric behavior of rulers and conquerors towards human beings and their rights." Such rhetoric fuels anxiety among some Turkish Muslims that Western concern for Hagia Sophia reflects a hidden plan to restore it to Christianity.

At the same time, Turkish Islamists demand the reconsecration of Hagia Sophia as a mosque, a position once espoused by Turkey's current prime minister, 54-year-old Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who, as a rising politician in the 1990s, asserted that "Ayasofya should be opened to Muslim prayers." (Erdogan frightened secularists even more at the time by declaring his support for introduction of Islamic law, announcing that "For us, democracy is a means to an end.") Erdogan went on to become mayor of Istanbul and to win election as prime minister in 2003. The effect of increased religiosity is evident in the streets of Istanbul, where women wearing head scarfs and ankle-length dresses are far more common than they were only a few years ago.

As prime minister, Erdogan, re-elected with a large majority in July 2007, shed his earlier rhetoric and has pursued a moderate and conciliatory course, rejecting political Islam, reaffirming Turkey's desire to join the European Union and maintaining—however tenuously—a military alliance with the United States. "Erdogan-type Islamists are resolved not to challenge through word or deed the basic premises of the secular democratic state that Turkey wants to institutionalize," says Metin Heper, a political scientist at Bilkent University in Ankara. Although Erdogan has not publicly repudiated his stance on reopening Hagia Sophia to Muslim prayer, he has scrupulously enforced existing law against it.

To more ideological Islamists, Hagia Sophia proclaims Islam's promise of ultimate triumph over Christianity. In November 2006, a visit by Pope Benedict XVI to Hagia Sophia prompted an outpouring of sectarian rage. The pope intended this as a gesture of goodwill, having previously antagonized Muslims by a speech in which he quoted a Byzantine emperor's characterization of Islam as a violent religion. But tens of thousands of protesters, who believed that he was arriving to stake a Christian claim to Hagia Sophia, jammed surrounding streets and squares in the days before his arrival, beating drums and chanting "Constantinople is forever Islamic" and "Let the chains break and Ayasofya open." Hundreds of women wearing head coverings brandished a petition that they claimed contained one million signatures demanding the reconversion of Hagia Sophia. Thirty-nine male protesters were arrested by police for staging a pray-in inside the museum. When the pope finally arrived at Hagia Sophia, traveling along streets lined with police and riding in an armored car rather than his open popemobile, he refrained from even making the sign of the cross. In the museum's guest book, he inscribed only the cautiously ecumenical phrase, "God should illuminate us and help us find the path of love and peace." (There still has been no real rapprochement between the Vatican and Turkish Islam.)

For secular Turks, also, Hagia Sophia retains power as a symbol of Turkish nationalism and Ataturk's embattled cultural legacy. Many are dismayed by the possibility of Islamic radicals taking over the building. "Taking Ayasofya back into a mosque is totally out of the question!" says Istar Gozaydin, a secularist scholar and expert on political Islam. "It is a symbol of our secular republic. It is not just a mosque, but part of the world's heritage."

As a symbol, its future would seem to be caught in an ideological no man's land, where any change in status quo threatens to upset the delicate balance of mistrust. "Hagia Sophia is a pawn in the game of intrigue between the secular and religious parties," says Ousterhout. "There's an alarmist response on both sides. They always assume the worst of each other. Secularists fear that religious groups are part of a conspiracy funded from Saudi Arabia, while religious people fear that the secularists want to take their mosques away from them." The situation is exacerbated by bitter battles over the larger role of Islam in political life and the right of women who wear Islamic head scarfs to attend schools and universities. "Neither side is willing to negotiate," says Ousterhout. "There's a visceral mistrust on both sides. Meanwhile, scholars fear offending either group, getting in trouble and losing their jobs. All this makes it harder and harder to work on Byzantine sites." Several attempts to finance large-scale restoration with funds from abroad have been stymied by suspicion of foreigners, a problem that has been made worse by the war in Iraq, fiercely opposed by a large majority of Turks.

Astonishingly—although many scholars have studied Hagia Sophia over the years—the building has never been completely documented. New discoveries may yet be made. In the 1990s, during emergency repairs on the dome, workers uncovered graffiti that had been scrawled by tenth-century repairmen, imploring God for protection as they worked from scaffolds 150 feet above the floor. "Kyrie, voithi to sou doulo, Gregorio," ran a typical one—"Lord, help your servant, Gregorius." Says Ousterhout, "You can imagine how scared they might have been up there."

Daunting work must be done for Hagia Sophia to survive for future centuries. "This is the premier monument of Byzantine civilization," says Ousterhout. "Old buildings like Hagia Sophia are ignored until there's an emergency. They're put back together and then forgotten about until the next emergency. Meanwhile, there is a continual deterioration."

Huge sections of ceiling are peeling and flaking, stained by water seepage and discolored by age and uneven exposure to light. Acres of stucco must be replaced. Windows must be repaired, new glass installed, warped frames replaced. Hundreds of marble panels, now grime-encrusted, must be cleaned. Irreplaceable mosaics must somehow be restored and protected.

"There is no long-term plan to conserve the mosaics that still survive," says art historian Teteriatnikov, who adds that a more coordinated effort is needed to protect the structure from earthquakes. "Hagia Sophia is uniquely vulnerable," says architectural engineer Stephen Kelley, "because, in an earthquake, unless a building acts as a single tightly connected unit, its parts will work against each other." The structure, he adds, comprises "additions and alterations with many natural breaks in the construction. We just don't know how stable [it] is."

"At this point, we don't even know how much consolidation and restoration the building needs, much less how much it would cost," says Verkin Arioba, founder of the Historical Heritage Protection Foundation of Turkey, which has called for an international campaign to save the monument. "How do we approach it? How should the work be prioritized? First we need to assess how much damage has been done to the building. Then we'll at least know what must be done."

Meanwhile, Hagia Sophia continues its slow slide toward decay. "We have to rediscover Hagia Sophia," said Zeynep Ahunbay, as we left the gloom of the antechamber and re-entered the nave. I watched a trapped dove swoop down through ancient vaults and colonnades, then up again toward the canopy of shimmering gold mosaic, its wings beating urgently, like the lost soul of bygone Byzantines. "It is a huge and complicated building," she said. "It has to be studied the way you study old embroidery, stitch by stitch."

Writer Fergus M. Bordewich frequently covers history and culture.

Photographer Lynsey Addario is based in Istanbul.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.