A Musical Tour Along the Crooked Road

Grab a partner. Bluegrass and country tunes that tell America’s story are all the rage in hilly southern Virginia

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Crooked-Road-Floyd-Country-Store-Jamboree-631.jpg)

Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains are known for their speed demons. The moonshiners of old tore over country roads in 1940 Ford coupes, executing 180-degree “bootleg turns” and using bright lights to blind the revenue officers shooting at their tires. Legend has it that many of Nascar’s original drivers cut their teeth here, and modern stock car design is almost certainly indebted to the “liquor cars” dreamed up in local garages, modified for speed and for hauling brimful loads of “that good old mountain dew,” as the country song goes.

Even now, it is tempting to barrel down Shooting Creek Road, near Floyd, Virginia, the most treacherous racing stretch of all, where the remains of old stills decay beside a rushing stream. But instead I proceed at a snail’s pace, windows down, listening to the burble of the creek, the gossip of cicadas in the dense summer woods, and the slosh of a Mason jar full of bona fide moonshine in the back seat—a gift from one of the new friends I met along the road.

Slow is almost always better in this part of the world, I was learning. A traveler should be sure to leave time to savor another ready-to-levitate biscuit or a melting sunset or a stranger’s drawling tale—and especially, to linger at the mountain banjo-and-fiddle jams that the region is known for. This music cannot be heard with half an ear—it has 400 years of history behind it, and listening to it properly takes time.

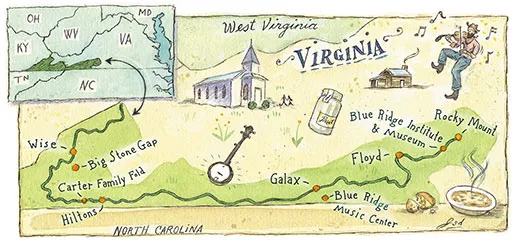

The Crooked Road, Virginia’s heritage music trail, winds for some 300 miles through the southwest corner of the state, from the Blue Ridge into deeper Appalachia, home to some of the rawest and most arresting sounds around. Most of the trail runs along U.S. 58, a straightforward multilane highway in some spots and a harrowing slalom course in others. But the Crooked Road—a state designation originally conceived in 2003—is shaped by several much older routes. Woodland buffalo and the Indians who hunted them wore the first paths in this part of the world. Then, in the 1700s, settlers came in search of new homes in the South, following the Great Wagon Road from Germantown, Pennsylvania, to Augusta, Georgia. Other pioneers headed west on the Wilderness Road that Daniel Boone hacked through the mountains of Kentucky. Some rode on wagons, but many walked—one woman told me the story of her great-grandfather, who as a child hiked with his parents into western Virginia with the family pewter tied in a sack around his waist and his chair on his back. And, of course, some fled into the mountains, long a refuge for escaped slaves.

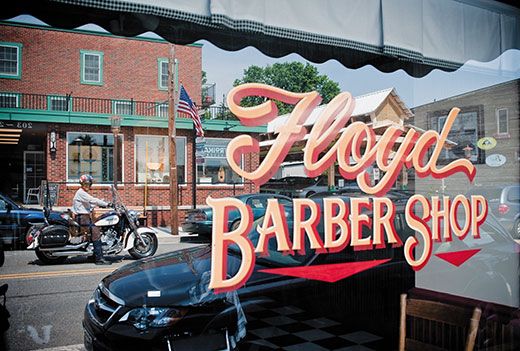

The diversity of settlers funneled into the region gave rise to its unique musical style. Today the “old-time” Virginia music—the forerunner of American country—is still performed not just at legendary venues such as the Carter Family Fold near Hiltons, Virginia, but at Dairy Queens, community centers, coon hunting clubs, barber shops, local rescue squads and VFW halls. A fiddle tune may be played three different ways in one county; the sound is markedly modified as you travel deeper into the mountains toward the coalfields. Some of the oldest, loveliest songs are known as “crooked tunes,” for their irregular measures; they lead the listener in unexpected directions, and give the music trail its name.

Except for a few sites, including a park near the town of Rocky Mount, where a surviving fragment of the Great Wagon Road wanders off into shadow, the older pathways have virtually disappeared. But the music’s journey continues, slowly.

Cheick Hamala Diabate smiled angelically at the small, bewildered crowd gathered in a breezeway at the Blue Ridge Music Center near Galax, Virginia. They had come expecting to hear Mid-Day Mountain Music with local guitar players, but here instead was a beaming African musician in pointy-toed boots and dark sunglasses, cradling an alien string instrument called a ngoni. Small and oblong, it is made of goatskin stretched over hollowed wood. “Old in form but very sophisticated,” whispered folklorist Joe Wilson, a co-founder of the center, a partnership between the National Park Service and the National Council for the Traditional Arts. “Looks like it wouldn’t have much music in it, but the music’s in his hands.”

Wilson is one of the Crooked Road’s creators and the author of the indispensable Guide to the Crooked Road. He had invited Diabate for a recording session, not only because the musician is a virtuoso performer nominated for a Grammy, but because the ngoni is an ancient ancestor of the banjo, often described as the most American of instruments. The ngoni’s shortened drone string, tied off with a piece of rawhide, is the giveaway—it’s a predecessor of the modern banjo’s signature abbreviated fifth string.

“This is a tune to bless people—very, very important,” Diabate told the audience as he strummed the ngoni. Later he would perform a tune on the banjo, an instrument he’d never heard of before immigrating to this country from Mali 15 years ago but has since embraced like a long-lost relative.

Captured Africans were being shipped to coastal Virginia as early as 1619; by 1710, slaves constituted one-quarter of the colony’s population. They brought sophisticated musical and instrument-building skills across the Atlantic and, in some cases, actual instruments—one banjo-like device from a slave ship still survives in a Dutch museum. Slaves performed for themselves (a late 1700s American folk painting, The Old Plantation, depicts a black musician plucking a gourd banjo) and also at dances for whites, where, it was quickly discovered, “the banjar”—as Thomas Jefferson called his slaves’ version—was much more fun to groove to than the tabor or the harp. Constantly altered in shape and construction, banjos were frequently paired with a European import, the fiddle, and the unlikely duo became country music’s bedrock.

In the 1700s, when the younger sons of Tidewater Virginia’s plantation owners began crowding west toward the Blue Ridge Mountains—then considered the end of the civilized world—they took their slaves with them, and some whites began picking up the banjo themselves. In the mountains, the new sound was shaped by other migratory populations—Anabaptist German farmers from Pennsylvania, who toted their church hymnals and harmonies along the Great Wagon Road as they searched for new fields to plow, and Scots-Irish, newly arrived from northern Ireland,who brought lively Celtic ballads.

Two hundred years later, the country music known as “old-time” belongs to anyone who plays it. On my first Friday night in town, I stopped by the Willis Gap Community Center in Ararat, Virginia, not far from where Diabate had performed, for a jam session. The place was nothing fancy: fluorescent lights, linoleum floors, a snack bar serving hot dogs and hot coffee. A dozen musicians sat in a circle of folding chairs, holding banjos and fiddles but also mandolins, dobros (a type of resonator guitar), basses and other instruments that have been added to the country mix since the Civil War. A small crowd looked on.

Each musician selected a favorite tune for the group to play: old-time, gospel or bluegrass, a newer country style related to old-time, but with a bigger, bossier banjo sound. An elderly man with slicked-back hair, a string tie and red roses embroidered on his shirt sang “Way Down in the Blue Ridge Mountains.” A harmonica player blew like a Category 5 hurricane. Even the hot-dog chef briefly escaped the kitchen to belt out “Take Your Burden to the Lord” in a rough-hewn but lovely voice. Flatfoot dancers stomped the rhythm in the center of the room.

Most claimed to have acquired the music through their DNA—they felt they’d been born knowing how to tune a banjo. “I guess everybody learned by singing in church,” said singer Mary Dellenback Hill. “None of us had lessons.”

Of course, they did have maestro uncles and grandfathers who’d improvise with them for hours, and perhaps fewer distractions than the average American child today. Some of the older musicians performing that night had been born into a world straight out of a country song, where horses still plowed steep hillsides, mothers scalded dandelion greens for dinner and battery-operated radios were the only hope of hearing the Grand Ole Opry out of Nashville, because electricity didn’t come to parts of the Blue Ridge until the 1950s. Poverty only increased the children’s intimacy with the music, as some learned to carve their own instruments from local hardwoods, especially red spruce, which gives the best tone. On lazy summer afternoons, fledgling pickers didn’t need a stage to perform—then as now, a front porch or even a pool of shade would do.

My husband and I traveled east to west on the Crooked Road, pushing deeper into the mountains each day. Touring the foothills, we sensed why so many homesteaders had decided to journey no farther. All creatures here look well fed, from beef cows in their pastures to the deer bounding across the road to portly groundhogs lolling in the margins. It’s hard not to follow suit and eat everything in sight, especially with old-fashioned country joints such as Floyd’s Blue Ridge Restaurant serving up bowls of homemade applesauce, heaping helpings of chicken pan pie and, in the morning, dishes of grits with moats of butter. Big farm breakfasts—especially biscuits and gravy—are mandatory, and tangy fried apple pies are a regional specialty.

Many public fiddle jams take place at night, so there’s plenty of time for detours during the day. One morning, I stopped by the Blue Ridge Institute & Museum near Rocky Mount, site of an annual autumn folk life festival that includes mule jumping and coon dog trials as well as a forum where old revenue officers and moonshiners swap stories. Although Roddy Moore, the museum’s director, relishes these traditions, he told me that this part of the mountains was never isolated or backward—the roads took care of that, keeping local farmers in contact with relatives in big cities. “What people don’t understand,” Moore says, “is that these roads went both ways. People traveled back and forth, and stayed in touch.”

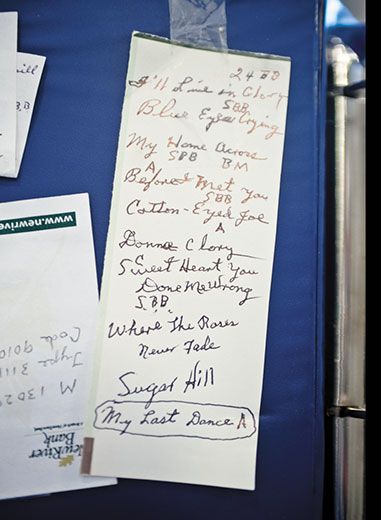

Especially around the one-stoplight town of Floyd, the outer mountains are becoming even more cosmopolitan, with chichi wineries, organic food shops and even a luxury yurt retailer. The 100-year-old Floyd Country Store still sells bib overalls, but now it also carries eco-conscious cocktail napkins. The old tobacco farms are disappearing—some fields have returned to forest, while others have been converted to Christmas tree farms. There’s a strong market for second homes.

Still, to an outsider, the place can feel almost exotically rural. Moore and I lunched at the Hub in Rocky Mount, where he mentioned it was possible to order a meal of cow’s brains and eggs. As I tried to mentally assemble this dish, a sociable fellow at the next table leaned over and advised: “Butter in a pan, break eggs over them. They’re really sweet. You would really like them if you wouldn’t know what they were.” Too bad I’d already ordered my ham biscuit.

And as much as people still migrate in and out of the outer Blue Ridge, there’s a feeling of timelessness about the region. At the Willis Gap jam, somebody mentioned “the tragedy in Hillsville,” a town in the next county over. I thought I must have missed a morning headline, before realizing that the man was referring to an incident that happened in 1912.

It all started when a member of the Allen clan kissed the wrong girl at a corn-shucking. A fistfight, several arrests and a pistol-whipping later, Floyd Allen, the family’s fiery patriarch, stood in the Hillsville courthouse, having just heard his jail sentence. “Gentlemen, I ain’t a’goin’,” he declared, and appeared to reach for his gun; either the court clerk or the sheriff shot him before he drew, and the courtroom—full of Allens and armed to the teeth—erupted in gunfire. Bystanders jumped out the windows; on the courthouse steps, Floyd Allen—injured but alive—attempted to mow down the fleeing jury. At the end of the shootout, five lay dead and seven were wounded. Bullet holes still pock the front steps.

But visitors to the courthouse should keep their opinions on the incident and its aftermath (Floyd and his son were eventually executed) to themselves. Ron Hall, my able tour guide and a mean guitar player to boot, told me that descendants of the Allens and other families involved still harbor hard feelings. The feud inspired at least two popular “murder ballads,” one of which memorializes the heroics of Sidna Allen, Floyd’s sharp-shooting brother, who had escaped the courtroom:

Sidna mounted to his pony and away he did ride

His friends and his nephews they were riding by his side

They all shook hands and swore they would hang

Before they’d give in to the ball and chain.

Stay alert when navigating the Crooked Road’s switchbacks and hairpin turns: around practically every corner lies a festival of some kind. There are annual celebrations for cabbages, covered bridges, maple syrup (sugar maples grow in the very highest elevations of the Blue Ridge), mountain leeks, hawks, tobacco, peaches, coal and Christmas trees.

In the pretty little town of Abingdon, we stumbled across the Virginia Highlands Festival. There we browsed handicrafts including lye-and-goats’ milk soap, mayhaw preserves (made from boggy, cranberry-like southern berries that taste like crabapples), and handmade brooms and rag rugs. Glendon Boyd, a master wooden-bowl maker, described his technique (“Start with a chainsaw. Guesswork.”) and the merits of local cucumber-magnolia lumber, which he prefers for his biscuit trays (“Cucumber, it takes a beating. It’s just good wood.”)

We were en route to what some consider the greatest country music venue of all—a cavernous tobacco barn in Poor Valley, at the foot of Clinch Mountain, known as the Carter Family Fold. As we ventured west, out of the Blue Ridge and into the Appalachians, the landscape began to change—the mountains becoming stonier and more vertiginous, the handmade wooden crosses on the side of the road taller, the houses huddled farther into hollows. Long grass lapped at prettily dilapidated outbuildings, sunlight cutting through the slats.

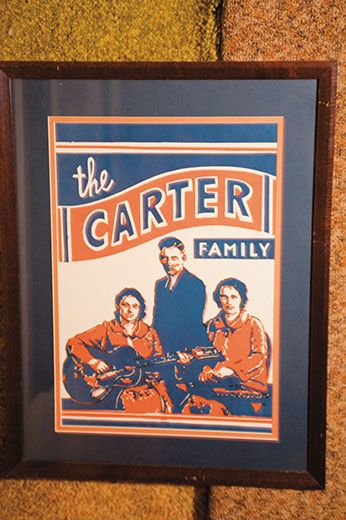

The Carters—A.P., his wife, Sara, and her cousin Maybelle—are often called the “first family” of country music. A.P. traveled through the Virginia hills to collect the twangy old ballads, and the group’s famous 1927 recording sessions helped launch the genre commercially. Maybelle’s guitar style—a kind of rolling strumming—was particularly influential.

In 1974, one of A.P. and Sara’s daughters, Janette, opened the Fold as a family tribute. Along with the big barn, which serves as the auditorium, the venue includes a general store once run by A.P. Carter, as well as his tiny boyhood house, which Johnny Cash—who married Maybelle’s daughter, June Carter, and later played his last concert at the Fold—had relocated to the site. Some diehards complain that the Fold has gotten too cushy in recent years—the chairs used to be recycled school-bus seats, and the big room was heated by pot-bellied stoves—but the barn remains rustic enough, admission is still 50 cents for kids and the evening fare is classic barbecue pork on a bun with a side of corn muffins.

Naturally, the Fold was hosting a summer festival too, which meant even bigger headliners than on a typical Saturday night. The place was packed to the rafters with old-time fans, some young enough to sport orange-soda moustaches, others old enough to balance oxygen tanks between their knees. Bands on stage played Carter standards (“Wildwood Flower”) and lesser-known numbers (“Solid Gone.”)

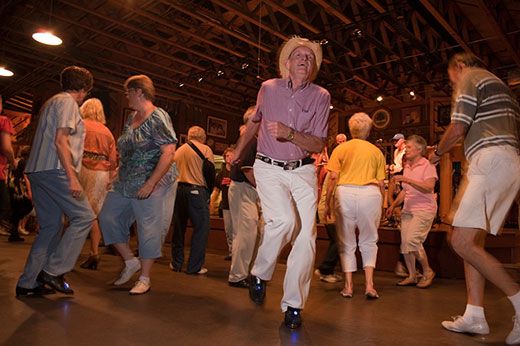

Throughout these performances, however, I noticed a strange nervous clicking sound, like fingers being frenetically snapped. Inspecting the area beneath our seats, I saw that many of our neighbors were wearing what looked to be tap shoes. When the Grayson Highlands Band came on, a wave of audience members swept onto the dance floor in front of the stage, with one man sliding, Tom Cruise-in-Risky Business style, into the center, blue lights flashing on his tap shoes. The traditional Appalachian dancing that followed—combinations of kicks, stomps and shuffles known as clogging—was dominated by strutting older men, some in silly hats. Professional cloggers, including women in red ruffled tops and patchwork skirts, joined the romp.

Dr. Ralph Stanley (he garnered an honorary doctorate in music from Tennessee’s Lincoln Memorial University) and the Clinch Mountain Boys closed the show. Stanley, one of the most celebrated country tenors around, is a shy, slight octogenarian who tends to sing with one hand tucked into his pocket. His white Stetson dwarfed him, although he wore a daringly sparkly string tie. His band includes his guitar-picking son, Ralph II; tiny Ralph III, age 3, also made a cameo appearance, strumming a digital toy guitar. “You’re going to hear Stanley music many, many years from now,” Stanley promised the delighted crowd.

But Dr. Ralph’s sound is also singular. His best-known performance is perhaps “O Death,” which he sang on the soundtrack for the 2000 film O Brother, Where Art Thou. (Although set in Mississippi, the film did wonders to promote Virginia country music.) Stanley grew up many miles north of the Fold, in Virginia’s remotest mountains, where the Crooked Road would lead us the next day. His voice—pure, quavering and full of sorrow—belongs to the coalfields.

Crushed up against the Kentucky border, the mountains of southern Virginia were among the last parts of the state to be colonized. Not even Indians built permanent dwellings, although they hunted in the area. The few roads there followed creeks and ridges—terrain too rugged for wagons. “You couldn’t get here,” says Bill Smith, tourism director for Wise County. “You could get to Abingdon, right down the valley, but not here.” After the Civil War, railroads broke through the hills to ferry out the region’s vast stores of coal. The coalfields have always been a world of their own. In near isolation, a haunting, highly original style of a cappella singing developed.

Travelers are still a relative rarity in these parts—Smith, a gregarious transplant from Montana, is the county’s first-ever tourism director. His wife’s family has lived here for generations. Revenue officers shot and killed one of Nancy Smith’s uncles while he was manning a whiskey still (moonshining is big on this end of the road, too) and it was her great-grandfather, Pappy Austin, who, as a child, carried the pewter and the chair. The family still has the chair, its worn-down legs a testament to the pleasure of sitting still. They don’t have the pewter—young Pappy, weary of the burden, simply dropped it off a mountain somewhere along the way.

I met Smith in Big Stone Gap, beneath the faded awning of the Mutual Drug, an old-style pharmacy and cafeteria of the type that once nourished every small town. Inside, older men tucked into platters of eggs, peering out from beneath the yanked-down brims of baseball caps.

People in these mountains don’t hide their roots. The window of the hardware store in nearby Norton—with a population of 3,958, Virginia’s smallest city—is full of honest-to-goodness butter churns. Many women won’t let you leave their home without a parting present—a jar of homemade chow-chow relish, perhaps, or a newly baked loaf of bread. Family cemeteries are meticulously tended—fresh flowers adorn the grave of a young woman who died in the 1918 flu epidemic. In the cemeteries, the old clans still host annual “dinners on the ground,” at which the picnicker keeps a sharp eye out for copperheads basking on the graves.

Coal is omnipresent here—in the defaced mountain vistas, in the black smears, known as coal seams, visible even on roadside rock faces, in the dark harvested mounds waiting to be loaded onto railroad cars. Many communities remain organized around company-built coal camps—long streets of rickety, nearly identical houses, with little concrete coal silos out front and miner’s uniforms, deep blue with iridescent orange stripes, hung on front porches. Men fresh from “under the mountain” still patronize local banks, their faces black with dust.

Coal was once a more generous king. The gradual mechanization of the mines eliminated many jobs, and some of the area’s productive coal seams have been exhausted. There are abandoned bathhouses, where miners once washed off the noxious black dust. Kudzu, the ferocious invasive vine, has wrestled some now-deserted neighborhoods to the ground.

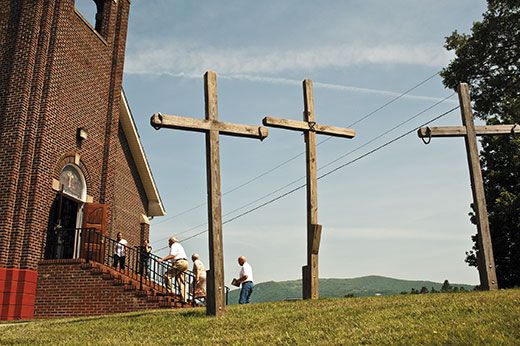

The threat of violent death, by cave-in or methane explosion, is still a constant for the remaining workers, and so the music here is steeped in pain and piety. From the lightless mines, the lyrics promise, leads a road to Paradise. Wise County is home to at least 50 Baptist and other congregations. Some of the churches are picturesque and white, others are utilitarian, little more than stacked cinderblocks. But almost all are well attended. “Prayer is our only hope,” reads a sign in front of one. In Appalachian music, “death is but an open gate to heaven,” Smith explains. “They’re going to the Beulah Land, the land of milk and honey. That is the music. They sing their pain, but also their particular view—that there’s a better life after this.”

The coalfields’ keening vocals—reflected in the sound of commercial artists like Stanley, Larry Sparks and Del McCoury—stem in part from the religious “line-singing” characteristic of the area. There weren’t always enough hymnals to go around at the little houses of worship, so a leader would sing out a single line for the rest to repeat. On summer Sundays it’s common to hear congregations—often one extended family—singing outside, the soloist and then the small group, their dolorous voices echoing off the hills.

As we drove past sheared-off mountain faces and a towering coal-fired power plant, Smith played recordings of Frank Newsome, a former miner many consider the greatest line-singer of all. While Newsome worked the somber lyrics, we heard in the background ecstatic yips from women in his congregation—taken by the spirit, they were “getting happy,” as it’s called. Newsome’s voice was melancholy and rough, a bit like Stanley’s with the showbiz stripped out of it. It was a voice dredged up from someplace deep, like coal itself.

The coalfields are a transporting destination, because the old music is still a living part of the contemporary culture. In other parts of America, “people look forward,” Smith says. “If you live here, they look back. The changes are coming and have been coming for a long time, but they come here slower. The people who stay here, that’s how they like it.”

Yet change they must, as the coal industry wanes and more jobs vanish. There are signs that tourism could be a saving grace: local jams assemble almost every night, except Sundays and Wednesdays (when many churches hold Bible study), and a winery recently opened near Wise, its vintages—Jawbone, Pardee, Imboden—named after regional coal seams. (“Strip mines turn out to be perfect for growing grapes,” Smith says. “Who knew?”) But vacant streets are a heart-wrenching commonplace in many little towns. High schools are closing, ending epic football rivalries. The fate of the music cannot be certain when the communities’ futures are in doubt. Not even Frank Newsome sings as he once did. He suffers from black lung.

After the beauty and pathos of the coalfields, I wanted a dose of good country cheer before heading home. We doubled back to the little Blue Ridge city of Galax, arriving just in time to hear the opening blessing and national anthem (played, naturally, on an acoustic guitar) of the 75th Old Fiddler’s Convention.

One early competitor, Carson Peters, ambled onstage and coolly regarded a crowd of about 1,000. Carson was not an old fiddler. He was 6 and had started first grade that very day. But he was feeling cocky. “Hello, Galax!” he squeaked into the microphone, poising his bow. I braced myself—plugged into a monster sound system, 6-year-olds with string instruments can commit aural atrocities.

But Carson—from Piney Flats, Tennessee, right across the Virginia border—was a savage little professional, sawing away at the old-time tune “Half Past Four” and even dancing a jig as the crowd roared.

“You’ll see some real ankle biters playing the heck out of the fiddle,” Joe Wilson had promised when I mentioned I was attending Youth Night at the longest-running and toughest mountain music showdown in Virginia. From toddlers to teenagers, in cowboy boots, Converse sneakers and flip-flops, they came with steel in their eyes and Silly Bandz on their wrists, some bent double beneath the guitars on their backs. Behind dark sunglasses, they bowed “Whiskey Before Breakfast” and a million versions of “Old Joe Clark.”

Galax was much changed since we’d last driven through. A sizable second city of RVs had popped up, and the old-time pilgrims clearly intended to stay awhile—they had planted plastic flamingos in front of their vehicles and hung framed paintings from nearby trees. I had heard that some of the best music happens when the weeklong competition pauses for the night, and musicians—longtime bandmates or total strangers—gather in tight circles around campfires, trading licks.

But the hard-fought stage battles are legendary too. “When I was a kid, winning a ribbon there was so important that it would keep me practicing all year,” said guitarist and luthier Wayne Henderson, once described to me as “Stradivarius in blue jeans,” who’d famously kept Eric Clapton waiting a decade for one of his handmade guitars. Henderson, of Rugby, Virginia, still keeps his ribbons—reams of them, at this point—in a box beneath his bed.

Fifteen years ago or so, many old-time festival musicians feared that youthful interest was waning. But today it seems that there are more participants than ever, including some from Galax’s burgeoning community of Latino immigrants, who came here to work in the town’s furniture factories. (The town now hosts powerful mariachi performances as well as fiddle jams, and one wonders what fresh musical infusions will come from this latest crop of mountaineers.)

Competitors hail from all over the country. I met four carrot-topped teenage sisters from Alaska, who had formed a bluegrass band, the Redhead Express. (Until recently, it had included their three little brothers, but the guys could no longer bear the indignity and had broken away to form their own unit, the Walker Boys.) Kids and parents had been touring the country for more than two years, practicing various instruments three at a time, up to eight hours a day, in a cramped and cacophonous RV. As soon as the youth competition wrapped up, the redheads faced a marathon drive to Nebraska for more shows.

Back in Galax, though, the music would proceed at a leisurely pace. For many children at the convention, as for generations of their ancestors, music was not so much an all-consuming occupation as a natural accompaniment to living, an excuse to enjoy friends and fine weather and stay up past bedtimes.

Erin Hall of Radford, Virginia, a 15-year-old with blue bands on her braces, had been fiddling since she was 5. During the school year, she plays classical violin, training in the Suzuki method. Come June, though, she switches to old-time.“It’s kind of like...” she paused. “Like my summer break.”

Abigail Tucker is the staff writer at Smithsonian. Photographer Susana Raab is based in Washington, D.C.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.