A Rally to Remember

Even at lollygagging speeds, Italy’s Mille Miglia road show stirs nostalgic hearts

Like many women in italy, 72-year old Maria Naldi watches the world from a window framed by dark green shutters. Through it, she looks out on a quiet piazza fronted by a 15th-century church. Beyond the church, the golden fields of Tuscany are sectioned by cypresses and crested by hilltop villages. Though the town, called Radicofani, boasts a thousand-year-old castle, it has no priceless Michelangelos or Raphaels. Yet one morning each year, Signora Naldi gazes upon masterpieces. Beginning at 10 a.m., four-wheeled works of art cruise in single file past a boisterous crowd gathered outside the Church of San Pietro. The artists’ names are well known here and to car buffs everywhere: Lancia. Mercedes-Benz. Porsche. Ferrari. In colors as loud as their engines, more than 300 classic automobiles roll by. Yet unlike the crowd waving small flags on the church steps, Signora Naldi doesn’t seem excited. The cars are all molto belle, she says, but it’s not like the old days. Back when she was a girl, they came through Radicofani as they do today. Back then, she remembers, they weren’t going only ten miles per hour.

In Italian, mille miglia means one thousand miles. Yet in Italy itself, the words mean much more. From the heyday of Mussolini to the dawn of la dolce vita, the annual Mille Miglia was Italy’s World Series, Super Bowl and heavyweight championship bout all rolled into one. Often touted as the greatest car race in the world, it sent foolhardy drivers dashing along winding, punishing roads. In their goggles and leather helmets, some of the world’s best piloti thundered through little towns at lunatic speeds. Cars careered around turns at 80 mph and roared through human tunnels of cheering fans. Drivers became legends, inspiring even more reckless heroics in the next Mille.

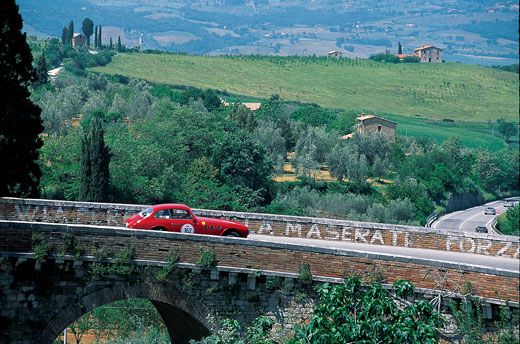

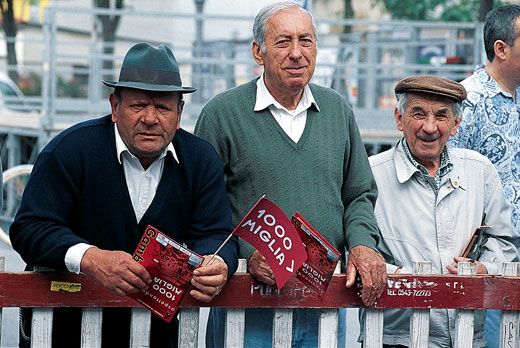

A tragic accident ended the race in 1957. For the next 20 years, as drivers in new cars won other races and got the plaudits, the older automobiles of the classical age sat in museums and garages, appreciated mostly by collectors. But then the Mille Miglia came to life again in 1977, not as a reckless suitor for the crowds’ adulation but as an aged, elegant lover still able to turn heads in the piazza. Now, each year, when spring brings scarlet poppies to the fields of central Italy, the Mille Miglia brings smiles along 1,000 miles of road. Sleek silver Mercedes slip under medieval arches. BMWs zing past Roman ruins. Sporty red Lancias snake through tiny towns with elegant names—Buonconvento, Sansepolcro, and Radicofani. And all along the course, up to a million people cheer the drivers, ogle the cars and remember.

Running on nostalgia rather than bravado, the Mille Miglia remains the greatest antique car rally in the world, even if the average speed is only 30 mph. And at exactly that speed, with occasional sprints to catch up, photographer Enrico Ferorelli, who was born in Italy, and I set out last May to chase the 2001 Mille Miglia. In a new station wagon, we doggedly followed the pack of priceless cars, sampling 1,000 miles of Italy in 48 hours. Florence, Siena, Cortona, Arezzo—town after town appeared in our windshield, whipped by our side windows and vanished in our rearview mirror. The Italians have a phrase for such a tour—fare un giro, “to take a spin.” And our 1,000-mile spin showed us this timeless country as it often sees itself—stylish, finely crafted and racing ahead without a care.

On a Thursday morning, two days before the Mille Miglia passed Maria Naldi’s window, crowds begin assembling in the Piazza Vittoria in Brescia, an industrial city in northern Italy. It was here in 1927 that four members of the local automobile club started a race to draw attention to their town. Since the 1890s, wild cross-country car rallies had been popular throughout Europe. Paris to Bordeaux. Paris to Berlin. Paris to Madrid. Several countries had banned such “races of death,” but that did not deter Italians. Here, the love of fast cars is matched only by what historian Jacob Burkhardt called Italy’s “national pastime for external display.” And on a sunny May morning, crowds line the Piazza Vittoria for a display called “the scrutineering.” One by one, 371 cars, some of the finest ever made, pull into the piazza to be scrutinized, registered and admired.

In the piazza, cars with running boards and spoked wheels sit behind cars that look like bullets. And big, beefy cars with top speeds of 83 mph stand beside low-slung rockets that cruise at 150 mph. Each Mille Miglia has a few famous people—our year the lineup included Formula One race car drivers, tennis star Boris Becker, and Miss Malaysia—but the cars themselves are the real stars. Cars like these do not have price tags; they have charisma. Yet even in a lineup of celebrities, some stand out. And so, even as a 1955 Porsche Spyder, the kind of car James Dean died in, rolls past the check-in, the local paparazzi focus on a Mercedes 300 SLR whose hood is stamped 722.

This was the very car British driver Stirling Moss took for a spin in the 1955 Mille Miglia. With his codriver consulting a long list of the race’s every turn, Moss saw all of central Italy between dawn and dusk. Out of the corner of his eye, Moss followed his codriver’s hand signals, enabling him to take tight corners in a blinding blur. Sometimes outpacing small aircraft above him, Moss hit 177 mph on some straightaways. Once, when his copilot failed to warn him of a bump, his car took off and flew for 200 feet before making a perfect four-point landing. Moss drove the 1,000 miles of impossibly twisted roads in just over ten hours, averaging about 98 mph, easily the fastest Mille ever.

Now, as number 722 pulls into the Piazza Vittoria, crowds gather round it, snapping photographs, peering into the cockpit, treating it with the awe earlier worshipers granted to holy relics. Moss’ Mercedes is followed by another fourwheeled celebrity. And another. And then, that evening, the cars line up again, this time at the starting line. In a pouring rain that drenches drivers in open cabs, the gorgeous old vehicles roll one by one down a ramp and set off for two days of punishment. It’s as if a lineup of supermodels strode down the runway of a Paris fashion show, then each put on sneakers and set out to run a marathon.

“The Mille Miglia created our automobiles and modern motoring,” observed the late Enzo Ferrari, whose cars won seven of the past ten races. “It enabled us to produce the sports cars that we now see all over the world. And when I say ‘we,’ I’m not just referring to Ferrari.” The old race was the ultimate test of driver and machine. Nearly a dozen drivers died, and the toll on cars was even worse. Cranked to the edge of engineering performance, some simply fell apart. Gearshifts snapped off in drivers’ hands. Axles broke. Brakes overheated. Transmissions failed, forcing drivers to finish the race in fourth gear. And those were just the cars that stayed on the road. In the wake of many a Mille, the lovely Italian countryside was littered with crumpled cars and shredded tires. But with every mile and every accident, the race’s fame grew, as did the names of a few drivers.

Every modern Mille entrant knows he or she is driving the same roads taken by Stirling Moss and by the race’s other legend, Tazio Nuvolari, the “Flying Mantuan.” In more than a dozen Milles, Nuvolari won only twice, but his heroics made him Italy’s answer to Babe Ruth. Handsome and absolutely fearless, he drove “like a bomb,” Italians said. Fans still debate whether he won the 1930 Mille by passing the leader in the dead of night with his lights off. And they still talk about the year he tossed his broken seat out of the car and drove on, perched on a sack of lemons he’d brought for nourishment. The car’s hood had flown off into the crowd. One fender was crumpled by a collision. His codriver pleaded with him to stop, to remove a dangerously hanging fender, but Nuvolari just shouted “Hold on!” He then aimed his car at a bridge and veered at the last second, neatly winging off the fender and speeding on. That was the old Mille. The new one is altogether more sane, if considerably less spicy.

On Thursday night, after driving through the downpour to the medieval town of Ferrara, soggy drivers grab a few hours of sleep. At 6 a.m., they are up and milling about their cars, ready to continue. Skies have cleared, and the cars glint in the Adriatic coast sunshine as they start a long day’s journey to reach Rome’s Colosseum by midnight. At the Mille’s height in the 1950s, news bulletins of the race-in-progress traveled by phone from Brescia to Rome and back: “Ascari is leading!” “Fangio is out of the race!” Parents woke their children before dawn to take them to the nearest town where the cars would pass. The route was lined with several million people—the men dressed in suits, the women in Sunday dresses—all shouting “Avanti! Avanti!”—“On! On!” Even today, in each town, drivers are greeted like conquering generals. Grandfathers sit grandsons on creaky knees and point out cars they saw when they were sitting on knees. Following close behind, Enrico and I are greeted by faces filled with bewilderment. What’s this station wagon doing among these supermodels? Yet we drive on. On past a castle in San Marino, a postage-stamp-size country completely surrounded by Italy. On through the tunnels of buttonwood trees lining the open road. On into a town with streets so narrow I can reach from the car to pluck a geranium from a window box while inhaling the aroma of cappuccino from an adjacent cafe. It would sure be nice to stop for a minute. But we have promises to keep, and miglia to go before we sleep.

Though not a race, the modern Mille does have a winner. At 34 points along the route, drivers undergo precise time trials. They must drive 7.7 kilometers in 10 minutes and 16 seconds, 4.15 kilometers in 6 minutes and 6 seconds, or some other exacting measure. During such trials, cars inch along, the copilot counting down the seconds till they reach the end: “Tre, due, uno.” Then they’re off with a roar. At race’s end, organizers will tally each driver’s points, with deductions for driving too fast or slow. But first, it’s on to the next crowded piazza. Each town seems slightly different. Some pay little attention to the passing parade. Others come out in force, with an announcer blaring the details and history of each passing car while local beauty queens hand drivers flowers. In Arezzo, where the Oscar-winning film Life is Beautiful was shot, tourists in the spectacular Piazza Grande toast the drivers. For an afternoon at least, life seems beautiful indeed, at considerable remove from the old race and its sad, abrupt end.

The winner of the 1927 mille averaged a mere 48 mph. But in each succeeding race, cars went faster. Although organizers tightened safety rules—crash helmets and some minor crowd control were introduced—by the 1950s the Mille Miglia was a tragedy just waiting to happen. In 1957, the race began with the usual mishaps. One car slammed into a house; no one was hurt. Another spun into a billboard. Spectators removed the debris and the driver went on. By the homestretch, more than one-third of the cars lay broken down along the course or had abandoned the race. The Italian Piero Taruffi led the pack, but coming up fast behind him was Spain’s dashing playboy, the Marquis de Portago, driving a 4.1-liter Ferrari. At a checkpoint in Bologna, the Marquis arrived with a damaged wheel but refused to waste time by changing it. Screaming ahead to catch Taruffi, he had hit 180 mph going through the small town of Guidizzolo when the damaged wheel disintegrated. The car somersaulted into the crowd, killing driver, codriver and ten spectators. The Italian government, which had long worried about such an accident, said basta. Enough. Surprisingly, there were few protests. “It was such a tragedy,” former driver Ettore Faquetti told me. “Everyone knew it was time. The cars were too fast. It had to end.”

In 1977, on the 50th anniversary of the first race, the Historic Mille Miglia rally debuted. Observing the speed limit—for the most part—the old cars strutted their stuff. Five years later, they did it again. In 1987, the event became an annual rally, and soon the race’s trademark red arrow could be found on ties, mugs, shirts, caps and other souvenirs. These days, owners of Sony’s PlayStation 2 can race the Mille Miglia as a video game. And if you own a pretty good car—valued, say, in the low six figures—you can drive in one of the rally’s many imitators in California, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado or New England. But the original has a distinct advantage. It has Italy. And through Italy the drivers roll, past the hilltop town of Perugia, then through charming Assisi and on toward the eternal city to which all roads lead.

Having plenty of its own museums, Rome is too sophisticated to pay much attention to a rolling car museum. Along the Via Veneto, a few heads turn and a few tourists call out. But the drivers who left Brescia to cheering crowds the night before, roll past the Roman Forum and the Colosseum largely unnoticed. At the Parco Chiuso, the halfway point, they come to a stop. Some retire for another short sleep. Others stay up to talk and swagger. Then, at 6:30 a.m., the rally is off again.

In charming Viterbo, I scan my guidebook. “Viterbo’s Piazza San Lorenzo has a 13th-century house built on Etruscan. . . . ” I read aloud, but by the time I finish, Viterbo is behind us. After a stop for gas—a full tank costs about $41—we’re winding uphill toward Radicofani where Maria Naldi is waiting. Watching the antique cars pass in all their glory, it’s easy to see why some drivers characterize their hobby as an insidious disease.

“When I got the car hobby sickness, I heard about this race real early,” says Bruce Male of Swampscott, Massachusetts, who ran the Mille in his 1954 Maserati. “I decided I had to do it.” Sylvia Oberti is driving her tenth straight Mille. In 1992, the San Francisco Bay Area native, who now lives in Italy, became the first woman to finish the 1,000 miles alone (or almost alone; she drives with her white teddy bear, Angelino). Why do they send irreplaceable cars down open roads dodging passing trucks and darting Vespa scooters? Each driver has the same answer: even a classic car was meant to be driven. “This is what you dream about,” says Richard Sirota of Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, competing in his first Mille, in a 1956 Ferrari 250 GT. “If you were into cars as a kid, everything you heard about was the Mille Miglia.”

On past Radicofani and through the rolling fields of Tuscany. Uphill through Siena’s spectacular Piazza del Campo, bigger than a football field, and back to the poppy fields again. Like tourists at a full-course Italian dinner, Enrico and I can’t take much more. Our eyes have feasted on one course after another. The hill towns of the Appenines as the antipasto. Arezzo and Perugia as the primo piatto, the first plate. Rome as the secondo. Then the tossed salad of Tuscany. We’re stuffed and we’re just coming to dessert: Florence. Here crowds of tourists line the Piazza della Signoria as the cars roll beneath the lofty Palazzo Vecchio before passing the soaring red-tiled Duomo. Finally, the road leads to the race’s most dangerous stretch, the FutaPass.

When the Mille Miglia began, this road was the only way to drive from Florence to Bologna. These days, most cars take the autostrada, but all along the two-lane blacktop overlooking the valley 2,000 feet below, families have come out to picnic and watch the nostalgic parade. Around one especially crowded 180-degree turn, I remember the words of Stirling Moss. “If you saw an enormous crowd, you knew it was a really bad corner,” Moss recalled in 1995. “If they were encouraging you to go faster, you knew it was even worse.” Climbing the pass, the road snakes like a blue highway in the Rockies. In the little town of Loiano, it cuts between a concrete wall and a row of bars filled with spectators. Back when he was a boy, spectator Vittorio Alberini tells me, the cars hit 100 mph through Loiano, zipping beneath spectators perched in trees.

Traversing the back side of the FutaPass, we roll to a stop beneath the leaning brick towers of Bologna. There we discover, after waiting 20 minutes to see others come through, that there are no more cars. We’re bringing up the rear. Enrico and I decide to take the autostrada. As if to outpace Moss himself, we race along the flat plain of Lombardy and reach the finish line before everyone else. We’ve won! OK, so we cheated, but our station wagon is here in Brescia before any of the classics. We bide our time till just after 9 p.m., when a stir goes through the bleachers lining the Viale Venezia. Behind a police escort, the first car to have driven all 1,000 miles—a 1925 Bugatti—comes in. One after another, bleary-eyed but smiling drivers thank the crowd and head back to their hotels to share stories of all the things that can happen to an old car in 1,000 miles.

Bruce Male got only eight hours of sleep during his run, but his Maserati “performed flawlessly.” Sylvia Oberti just barely finished the race thanks to her backup team and a spare fuel pump. And Richard Sirota’s Ferrari blew a clutch outside San Marino and dropped out of the rally. “No matter what, we finish next year,” he promised.

Mille Miglia 2001 was “won”—getting to the checkpoints at the appointed time—by two gentlemen from Ferrara, Sergio Sisti and Dario Bernini, driving a 1950 Healey Silverstone. They were given a silver trophy at a Sunday morning ceremony filled with speeches about Mille, old and new. As they spoke, I remembered Maria Naldi and her window in Radicofani. All would be quiet in the piazza now. Nothing to see from her window but a glorious 15th-century church, a thousand-year-old castle, the rolling hills of Tuscany and dashing young drivers in sleek machines roaring through her memories.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.