A Road Less Traveled

Cape Cod’s two-lane Route 6A offers a direct conduit to a New England of yesteryear

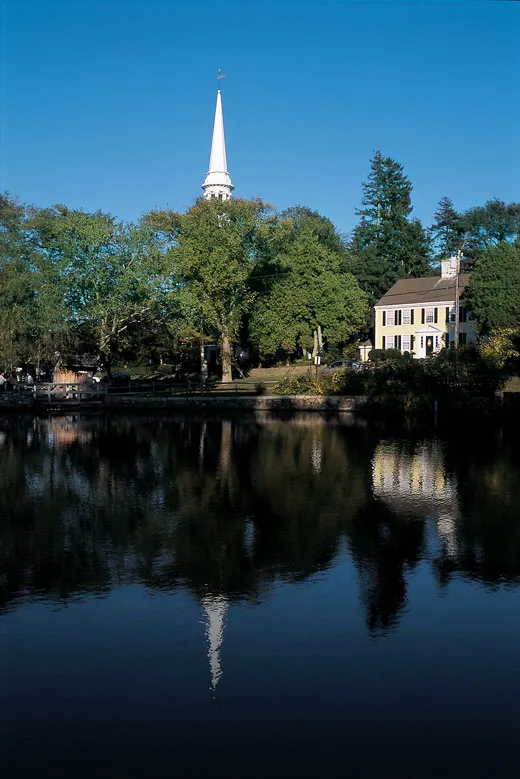

Landscapes, like beauty, may well be colored by the eye of the beholder, but steering along tree-shaded Route 6A on a mild summer day, with blue inlets of Cape Cod Bay on one side and white picket-fenced houses on the other, I'm tempted to conclude this may be the most appealing stretch of America I know. The 34-mile, two-lane road, also known as Old King's Highway, begins in the west where Cape Cod thrusts out of the Massachusetts mainland and ends in the east where the peninsula narrows and veers abruptly north. (Another fragment of 6A, perhaps ten miles or so, lies at the outer reach of the cape, near Provincetown.)

In between is a world of wonders: salt marshes and tidal flats that are cradles of marine life; woodlands reminiscent of the Berkshires; genealogy archives that draw would-be Mayflower descendants; church graveyards containing headstones dating back to the early 1700s; a thriving playhouse that has launched the careers of Hollywood stars; and museums that swell with visitors when the cape's temperamental weather turns soggy.

"6A's charm is no accident—it involves a lot of self-control," says Elizabeth Ives Hunter, director of the Cape Cod Museum of Art, in the town of Dennis (pop. 13,734), the midway point on the route. Every community along the way is subject to rules set by the individual town historic commissions. And they are absolutely inflexible. Signs, for instance. I drive past the Cape Playhouse in Dennis several times before finally spying a very discreet wooden slat bearing its name. "That's written large by 6A standards," managing director Kathleen Fahle assures me. "If we ever touched that road sign, we would never be allowed to put it back up again."

The theater itself has barely been altered during its 77-year existence. On its inauguration day, July 4, 1927, heavy rains leaked through the roof, forcing the audience to huddle under umbrellas at a performance of The Guardsman, starring Basil Rathbone. "That wouldn't happen today," says artistic director Evans Haile, although he does admit that some pinhole-size roof punctures do exist. Fortunately, most productions take place in fair weather. On a warm Saturday evening, I enjoy a rousing rendition of On Your Toes, a 1936 Rodgers and Hart musical.

Bette Davis began her career here as an usher, and Humphrey Bogart, Henry Fonda and Gregory Peck all honed their skills here before taking Hollywood by storm. Already a superstar in the 1950s, Tallulah Bankhead arrived, pet leopards in tow, for her Dennis engagements. Actress Shirley Booth, star of the 1960s sitcom "Hazel," performed here often late in her career, during the 1970s; she bequeathed to the playhouse her 1953 Oscar (for best actress in the role of Lola Delaney in Come Back, Little Sheba).

The theater harks back to an era before air conditioning, when Broadway closed for the summer. Plays and casts survived by touring the country; vacation retreats became important venues. Back then, performers could easily find lodging in Dennis. "We had 'landlady houses,' owned by widows who welcomed actors as guests," says Fahle. But as real estate prices soared, the notion of inviting strangers to lodge for weeks at pricey vacation homes lost its appeal.

Sharing the same plot of land as the playhouse is the Cape Cod Museum of Art. "From late June through July, we go for very accessible exhibitions," says director Hunter, citing marine scenes by Cape Cod painters or, more recently, the patriotic quilts and paintings of Ric Howard (1912-96), an illustrator who designed Christmas cards for the White House before retiring to Dennis. "By August, we are moving into edgier works," such as the recent retrospective of Maurice Freedman (1904-84), a New York City painter strongly influenced by the colors and patterns of the German Expressionists—and lured to Cape Cod by its summer light.

All of the museum's 2,000 works of art have a Cape Cod connection. The artists must either have lived or worked on the peninsula at some point—although this criterion has been broadened to include the nearby islands of Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard. "They are geologically related to Cape Cod," says Hunter with a smile.

The cape was formed by a glacier that retreated some 15,000 years ago, leaving behind the bay and the sandy peninsula that is constantly battered and reshaped by the Atlantic Ocean. By 8,000 years ago, the rising ocean had separated Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard from the peninsula's southern coast. "The basic fact of life around here is erosion," says Admont Clark, 85, a retired Coast Guard captain and founder of the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History, in Brewster (pop. 8,376), a few miles east of Dennis. "Every year, about three feet of beach are washed away and deposited elsewhere on the cape." It is pretty much a zero-sum game in the short run. But over a century or so, some ten inches of coastline are lost altogether.

During the past decade, two lighthouses, wobbling on bluffs undercut by constant waves, had to be placed on flatbed trailers and moved to more stable locations. Islets and inlets are repeatedly exposed and submerged, forcing harbor masters to update their maps frequently. Residents pay close attention to approaching storms, boarding up windows and otherwise battening down.

To walk Cape Cod's beaches and tidal flats is to be made aware that the terrain and waters shift by the hour—or the minute. The tides can fatally fool even the most knowledgeable old-timers. In the reedy wetlands behind my beachside bed-and-breakfast, I encounter the carcass of a seal, marooned by a rapidly receding tide. Clark recalls an ill-fated, 90-year-old farmer who scoured the flats for clams all his life. "One day about ten years ago the clamming was so good that he wasn't watching the rising waters around him," says Clark. "He drowned trying to swim back."

On an outing with Irwin Schorr, volunteer guide for the Museum of Natural History, I experience the vitality of this landscape. At his suggestion, I jump on a patch of grass—and bounce as if it were a mattress. "It's because of the constant tidal flooding," says Schorr. "Water is absorbed in between the grass roots and filtered underground into our aquifer."

When marsh grasses die, their stalks are absorbed into a spongy network of roots, forming peat. Bacterial decomposition nourishes crabs, crayfish and snails that in turn attract larger marine life and birds. Along the edges of a wood-planked walkway, I peer at fish—sticklebacks and silversides—feeding on mosquito larvae. The tide has risen so high we have to take off our shoes, roll up our pants and wade barefoot. A snaking column of recently hatched herring, glimmering in the tide, streaks toward the bay. Their timing is exquisite: within an hour, the water has receded so far there is a hardly a puddle left in the marsh. "The tide here rises and falls seven to nine feet every day," says Schorr.

Ranger Katie Buck, 23, patrols Roland C. Nickerson State Park, at the eastern end of the main part of 6A. The 2,000-acre preserve is a forest of oak, pine and spruce, populated by deer, raccoons, fox, coyotes and enough frogs to belie any global amphibian crisis.

"Sometimes there are so many they stick to the door and windows of our station," says Buck.

The park was named after a banking and railway tycoon who used it as a wild game preserve in the early 1900s. Roland Nickerson imported elk and bear for weekend guests to hunt. In 1934, his widow donated the property to the state. During the Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps planted 88,000 trees and built roads and trails throughout. The park is so popular that campsites, especially those for trailers, must be booked months ahead. The biggest attractions are "kettle ponds," some as large as lakes, created millennia ago by huge melting ice chunks left behind by retreating glaciers. "The water here is a lot warmer than the ocean or the bay," says Buck.

For me, sunny mornings are for visits to old church graveyards. On the grounds of the First Parish Church of Brewster, I meet up with John Myers, 73, and Henry Patterson, 76, parishioners and history buffs. First Parish was once a favorite of sea captains; many are buried in the adjoining graveyard. Each pew bears the name of a shipmaster who bought the bench in order to help fund the church, whose origins go back to 1700. But such generosity did not guarantee everlasting gratitude. "The church was always short of money, so ministers would periodically decree that the pews be put up for auction," says Patterson.

Etched on a wall is a list of long-dead captains, many of them lost at sea. Land was no safer, as many of the 457 headstones in the graveyard attest. Some belong to soldiers of the Revolution or the Civil War. But far more mark the remains of loved ones whose premature deaths could provoke bitterness verging on blasphemy. For the 1799 epitaph of his 2-year-old son, the Rev. John Simpkins wrote: "Reader, let this stone erected over the grave of one who was once the florid picture of health but rapidly changed into the pale image of death remind thee that God destroyeth the hope of man."

Patterson and Myers discovered, too, some dark footnotes to Brewster's history as they sifted through the church archives. At elders' meetings going back more than two centuries, sinners confessed to adultery, drunkenness, lying and theft. The most scandalous case involved that quintessential American optimist, Horatio Alger, the famed author of 19th-century rags-to-riches tales for young readers. After two years as minister of First Parish Brewster, Alger was dismissed by the church board in 1866 on charges of "unnatural familiarity with boys." He never returned to Brewster nor took up the pulpit again anywhere. "We probably launched his literary career by firing him," Myers deadpans.

Much of the archival research on Cape Cod is of a more personal nature—people trying to discover family roots. In Barnstable (pop. 48,854), another town on 6A, 13 miles from Brewster, the Sturgis Library, whose foundation was laid in 1644, draws amateur genealogists from all over. "The earliest settlers in Barnstable had Pilgrim relatives, so we get a lot of visitors trying to qualify for membership in the Mayflower Society," says Lucy Loomis, the library's director. Others seek connections, however tenuous, to the Presidents Bush, Benjamin Spock or any number of famous Americans whose ancestors lived in or near Barnstable centuries ago.

Visitors with quirkier research in mind also pore over the rich collection of local newspapers, merchant shipping records and documents donated to the library over many generations. A Californian recently spent two weeks at Sturgis looking for information about an ancestor who survived a 19th-century shipwreck and headed West with the Mormons. He "wanted to know if being saved from drowning had led his ancestor to a religious conversion," says Loomis.

Indeed, no personage or landmark is safe from scrutiny by history sleuths. No sooner have I begun sounding like a "wash-ashore"—as natives refer to a newcomer besotted enough by the cape to move here—than local historian Russell Lovell lets me in on a secret: Route 6A is of far more recent vintage than colonial times. "The name 'Old King's Highway' is a publicity gimmick," says the tall, lean octogenarian. The road was built largely in the 1920s when cars began replacing trains.

Lovell, a Sandwich (pop. 21,257) resident who wrote a 611-page tome that traces the town's history from a Pilgrim settlement in 1637 up to the present, leads me on a tour of what is most historically authentic about the place—17th-century wood-shingled houses built in the famed Cape Cod saltbox design, and the Sandwich Glass Museum, where hundreds of locally produced 19th- and early-20th-century collectibles, from kitchenware to lamps, are on display.

But like many first-timers, what I most want to do is visit Sandwich's famed antique automobile collection at the Heritage Museums & Gardens, a former private estate. Some 34 classic cars are housed in a Shaker-style round stone barn. ("The Shaker concept was that no devils could leap out at you if there were no corners for them to hide," Charles Stewart Goodwin, acting director of Heritage, tells me.) The collection includes a 1909 White Steamer, a 1912 Mercer Raceabout, a 1932 Auburn Boattail Speedster—and my favorite, a 1930 Duesenberg.

This one happens to have been owned by Gary Cooper. The star had the chassis painted yellow and lime and the seats upholstered in green leather. "He and Clark Gable used to race their Duesenbergs down the streets of Hollywood," says Goodwin. That's not the sort of behavior that would be tolerated along 6A. But then again, tasteful restraint, rather than glamorous excess, has always been the hallmark of this remarkable American conduit to our past.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.