A Short Talk With a Legend of Rock

“Climbing without risk isn’t climbing,” says Yvon Chouinard, American rock climbing pioneer and founder of Patagonia

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120403030031ElCapSMALL.jpg)

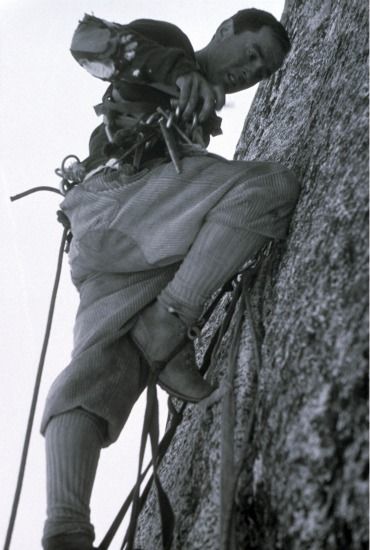

Until 1958, no person in known history had climbed the face of what may be the world’s most famous cliff, Yosemite’s El Capitan.

In the 54 years since climbing greats Warren Harding, George Whitmore and Wayne Merry made the first ascent, “El Cap” has been scaled thousands of times. Many individuals have climbed the 3,000-foot wall by numerous routes, and today dozens of climbers may be on the face of the cliff at any given time, nearly every month of the year. Scraps of dropped camping debris litter the valley floor, including bags of human waste, though “poop tubes” are now required of multi-day climbers. Today, just going up is hardly even an achievement in the climbing community, and so climbers bent on setting records or gaining praise must attempt such stunts as solo climbing and speed climbing. It’s been the same story for many of the great walls around the world: Once unclimbed, they are now mostly old news. Pitons scar many of them from base to top, and chalk smudges indicate clearly where a thousand climbers before have anchored their fingertips. For each successive person who goes up—each taking advantage of advances in knowledge, technology and gear—the challenge of the climb loses another trace of its old glory.

But Yvon Chouinard remembers the early years of the sport. He was among the pioneers of modern rock climbing and has climbed El Cap six times, two of which were first ascents of unmarked routes. Chouinard, who lives in Ventura County, began climbing as a kid in the 1950s, when he and several friends began making their first trips to Yosemite. At the time, campsites in the national park were always plentiful—though climbing gear was not.

“We were stealing hemp ropes from the telephone company,” he recalled with a laugh as he spoke to me by phone recently. “We had to learn on our own. There were no schools back then.”

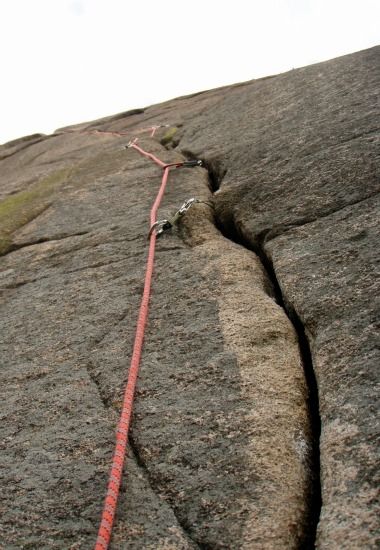

Common practice of the era was to pound bolts into the rock; climbers secured their ropes—and their lives—to these bolts in case of a fall. But Chouinard was among the first people to consider the adverse effects this was having. So he designed his own form of removable pitons and began selling them to others in the small but growing circle of climbers. Eventually he invented gear that could be wedged into cracks, then removed again, leaving the rock unmarked. Later still, Chouinard began making clothing suited for the rigors of scaling cliffs, and in 1972 he founded a little company called Patagonia. It would grow into one of the best-known names in outdoor apparel.

In the 1950s, Chouinard says, there were fewer than 300 climbers in America. Most routes, whether climbed previously or not, were still un-scarred by either chalk or metal, and Chouinard grew high on the challenge and the danger of ascending routes while feeling the rock with his free hand, reaching, sometimes straining, looking for that next hold.

Today, hundreds of thousands of climbers scale walls around the world. I asked Chouinard if this—the growing popularity of climbing—is good for the world, good for people and maybe even good for the rock.

“It would be good because it’s getting people outdoors and into natural places,” he said—except that, inevitably, the Earth’s great walls have suffered. “Today, you go up a route that people climbed in the 1920s using hemp ropes and pitons, and there’ll be a bolt every 15 feet—and next to a crack. It’s really unfortunate.”

Modern climbing has become commercialized, too, and increasingly competitive. Sponsorships and financial motivation to break records or just gain glory may push climbers beyond their own limits. “And that,” Chouinard said, “can kill you.”

Long ago, Chouinard and his contemporaries committed themselves to an unofficial set of climbing ethics, which foremost mandate that a cliff be left as nature made it; for the next climber, so went the idea, there should be no evidence of a prior climber’s passage. “If you’re going up a route that’s been climbed without gear a thousand times and you’re putting bolts into the rock, you’re ruining the whole experience for the next person,” Chouinard explained. He cites what he calls the “manifest destiny idea, especially in Europe,” about “conquering the mountain and making it easier for the next person.” By such a process, Chouinard says, the magic is all but lost as cabins and cable cars are built on its slopes.

In Yosemite, where the cliffs remain mostly as they always were, simply the crowds of people clamoring to get their hands on some rock may have diminished the experience. The park service estimates that climbers log between 25,000 and 50,000 “climber-days” per year. Chouinard rarely visits the park anymore simply because of the difficulty in reserving a campsite. He feels the cables that lead up the back side of Half Dome should be removed, leaving this granite cathedral to the skilled and the impassioned—or no one at all.

Today, the popularity of rock climbing has spurred the proliferation of urban climbing gyms. But whether these facilities of synthetic rock, shredded rubber floors and fluorescent lighting are the modern climber’s answer to the urge to go up is questionable. Chouinard thinks that gyms simply don’t replicate the real spirit of rock climbing. “Climbing without risk isn’t climbing,” he says. “And in gyms, there’s no risk. You aren’t leading, and you’re not using your head. You’re just following the chalk marks to the top.”

So if gyms don’t cut it, and if even Yosemite—the Mecca of great walls and sacred rock—has lost its excitement, where on Earth can a modern climber go to find what Chouinard, Harding, Tom Frost and other Golden Age rock legends enjoyed five decades ago? Chouinard says that Sub-Sahara Africa, the Himalayas and Antarctica each offer pristine climbing opportunities. In the United States, he says, Alaska still offers untouched cliffs. And that’s all the hints we’ll give, and we’ll leave the thrills of discovery to you. And remember: If you follow the chalk marks, you’ll get to the top—but are you really climbing?

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)