A Tour of California’s Spanish Missions

A poignant reminder of the region’s fraught history, missions such as San Miguel are treasured for their stark beauty

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/California-Missions-San-Miguel-belltower-631.jpg)

Shirley Macagni, a 78-year-old retired dairy rancher and great-grandmother of seven, is an elder of the Salinan tribe, whose members have inhabited California’s Central Coast for thousands of years. Macagni calls her oak-dotted ancestral region, a largely unspoiled terrain of orchards, vineyards and cattle ranches, a “landscape that still stirs people’s imaginations.”

Spanish settlers, arriving in the late 1700s, would decimate the tribe through smallpox, servitude and other depredations; resistance was dealt with harshly, and, says Macagni, fewer than a thousand Salinan survive today. The Spaniards’ legacy is complicated, and, Macagni feels, it is unfair to judge 18th-century attitudes and actions by contemporary standards. “They didn’t deliberately say they’re going to destroy people,” she says. “Records show that [the Salinan] were housed and fed and taught. My [ancestral] line developed into some of the best cattlemen and cowboys in the country. They learned that through the Spanish padres and the army that came with them.”

By delving into 18th-century parish archives, Macagni has documented her family’s links to the region’s earliest European outposts: Franciscan missions founded to convert the native population and extend Spain’s colonial empire northward into virgin territory the settlers called Alta (Upper) California. Macagni is especially proud of the Salinan connections to Mission San Miguel, Arcángel, ties that go back to its founding in 1797. She has fond memories of childhood outings and fiesta days there. “For as long as I can remember,” she says, “tribal members, the elders and the children were held in great regard.” Although she is not Catholic—she follows tribal beliefs—Macagni became active in fundraising efforts to preserve and restore Mission San Miguel after it was badly damaged in 2003 by the San Simeon earthquake. “It’s not just my history,” she says. “It’s part of the history of our whole country.”

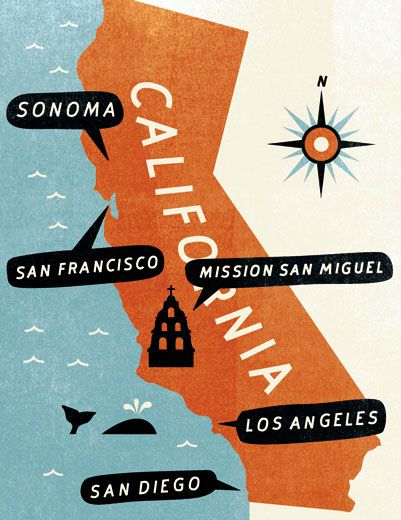

Nestled in a remote valley, Mission San Miguel was the 16th of 21 missions built between 1769 and 1823 in a chain that stretches 600 miles from San Diego to Sonoma. Each was a day’s journey on horseback from the next along the fabled El Camino Real, which roughly corresponds to today’s U.S. Highway 101. Spanish settlement—its presidios (forts), pueblos (towns) and missions—gave rise to Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose and other urban centers that underlie California’s standing as the nation’s most populous state (37.3 million), home to nearly one out of eight Americans.

For many, the missions lie at the very heart of the state’s cultural identity: cherished symbols of a romanticized heritage; tourist destinations; storehouses of art and archaeological artifacts; inspirational settings for writers, painters and photographers; touchstones of an architectural style synonymous with California itself; and active sites of Catholic worship (in 19 of the 21 churches). “There are few institutions in California that have become imbued with a comparable range and richness of significance,” says Tevvy Ball, author, with Julia G. Costello and the late Edna E. Kimbro, of The California Missions: History, Art, and Preservation, a lavishly illustrated volume published in 2009 by the Getty Conservation Institute.

Not long after Mexico achieved independence from Spain in 1821, the missions were secularized. “Following the gold rush in 1848 and California statehood in 1850,” Ball says, “the missions were largely forgotten and were often viewed as relics of a bygone civilization by the new American arrivals.” Gradually, by the 1870s and ’80s, the landmarks gained popularity. “The romance of the missions was spread by an assortment of boosters and writers, some of whom had a deeply genuine love of the mission heritage,” Ball adds. “And through their efforts over the next few decades, the missions became, particularly in Southern California, the iconic cornerstones of a new regional identity.” The uplifting tale of the Franciscans spreading Christian civilization to grateful primitives—or the “mission myth,” as it has come to be known—omits uncomfortable truths. Yet the power of that traditional narrative largely accounts for the missions’ survival today, Ball says.

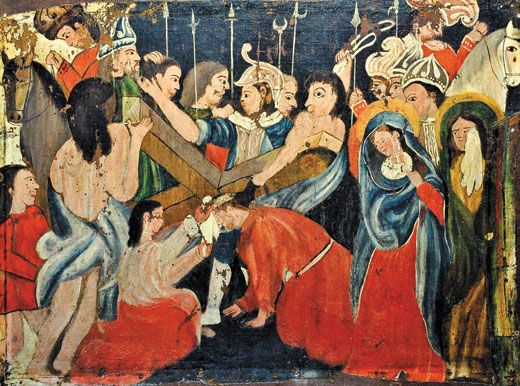

What distinguishes mission san miguel is its stark authenticity—no romantic reinventions of history—just the real thing, much as it might have appeared generations ago. Of the 21 missions, San Miguel contains the only surviving original church interior. An extraordinary profusion of colors, materials and designs—including original Native American motifs—has remained largely intact from the time of their creation. Ornamentation is executed in a palette of pale green, blue, pink, lavender, red and yellow pigments. The richly decorated retablo, or altarpiece, includes a painted statue of the mission’s patron saint, gazing skyward at a rendering of the all-seeing eye of God, depicted as floating within a diaphanous cloud. Much of the work was designed by a celebrated Catalan artist, Esteban Munras, and is believed to have been executed by Salinan artisans who had converted to Christianity.

Unlike other missions, where original motifs were modified, painted over or covered with plaster, San Miguel benefited from a kind of benign neglect. “It was in a small rural community and didn’t have a lot of money, so it was left alone—that’s kind of the miracle of San Miguel,” says archaeologist Julia Costello. “The bad news, of course, is that it sits pretty much near an earthquake fault.” Specifically, the San Andreas fault.

On the morning of December 22, 2003, a quake registering a magnitude of 6.5 jolted California’s Central Coast, seriously damaging buildings at Mission San Miguel, including the church and the friars’ living quarters. Experts feared the cracked walls of the sanctuary could collapse, destroying its historic murals.

Overcoming these challenges has required an ongoing collaborative effort among engineers, architects, conservators, archaeologists and other specialists—backed by foundations and other groups seeking to raise more than $12 million. The top priority was seismic strengthening of the mission church, which took two years and drew on cost-effective, minimally invasive techniques pioneered by the Getty Seismic Adobe Project. Anthony Crosby, preservation architect for Mission San Miguel, describes the chief aim of seismic retrofitting in one word: ductility—“the ability of a system to move back and forth, swell and shrink, and return to where it was in the beginning.”

Since the church’s reopening in October 2009, increasing attention has focused on preserving its murals and woodwork. “Walking into the church, you really are transported back,” says wall painting conservator Leslie Rainer, who’s assisting on the project. “It’s the experience you would want to have of the early California missions, which I find lacking in some of the others.” Rainer also appreciates the countryside and the nearby town of Paso Robles, a mecca for food and wine enthusiasts. “There’s an old plaza, a historic hotel and fancy little restaurants,” she says. “Then you go up to San Miguel and you have the mission. It’s all spectacular scenery, valleys and then hills, and it’s green and beautiful at the right time of year,” late autumn into spring.

It has taken more than expert teams to revive Mission San Miguel’s fortunes. Shirley Macagni has brought in Salinan families and friends to help out, too. One day she organized volunteers to make hundreds of new adobe bricks using soil from the mission grounds. “That was a great experience for all of us,” she says. “The children really, really appreciated it, knowing that our ancestors were the ones that built the mission.” She pauses to savor the thought. “Hey, we built this. We made these bricks and we built it. And now look at it. Even the earthquake didn’t knock it down.”

Jamie Katz reports frequently on history, culture and the arts. Photographer Todd Bigelow lives in Los Angeles.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)