A Walk Through Old Japan

An autumn trek along the Kiso Road wends through mist-covered mountains and rustic villages graced by timeless hospitality

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Kiso-Road-Nakasendo-road-stone-631.jpg)

“It is so quiet on the Kiso that it gives you a strange feeling,” Bill read, translating from a roadside sign in Japanese. Just then a truck roared past.

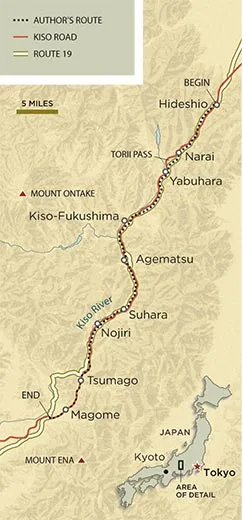

My friend Bill Wilson and I were standing at the northern end of the old Kiso Road, which here has been replaced by modern Route 19. It was a sunny fall morning, and we had taken the train from Shiojiri, passing schoolgirls wearing blue uniforms and carrying black satchels, to Hideshio, a kind of way station between plains and mountains. With backpacks buckled, we had headed off into the hills.

Now we were walking south along the highway, separated by a guardrail from the speeding traffic. For centuries, the 51-mile Kiso Road was the central part of the ancient 339-mile Nakasendo, which connected Edo (Tokyo) and Kyoto and provided an inland alternative to the coastal Tokaido road. For centuries, merchants, performers, pilgrims, imperial emissaries, feudal lords, princesses and commoners traveled it. “Murders, robberies, elopements, love suicides, rumors of corruption among the officials,” Shimazaki Toson wrote in his epic novel, Before the Dawn, “these had all become commonplace along this highway.”

Shimazaki’s 750-page work, published serially beginning in 1929, depicts the great political and social upheavals of mid-19th-century Japan: a period when foreign ships began appearing off its shores and its people made the difficult transition from a decentralized, feudal society ruled by shoguns to a modernizing state ruled by the central authority of the Meiji emperor. Shimazaki set his story in his hometown of Magome, one of the Kiso Road’s 11 post towns (precursors of rest stops). Hanzo, the novel’s protagonist, is based on Shimazaki’s father, who provided lodging for traveling officials. In capturing the everyday workings and the rich culture of the inland highway, Shimazaki exalted the Kiso in much the way that the artist Hiroshige immortalized the Tokaido in his woodcuts.

Hiroshige painted the Kiso also (though not as famously), and even from the highway we could see why. Turning our eyes from the cars, we gazed at hillsides of green and muted orange. A lone Japanese maple would flash flaming red, while russet leaves signaled a cherry tree’s last autumnal act. Other branches stripped of foliage bore yellow persimmons that hung like ornaments. After an hour and a half of walking, we came to a stand of vending machines outside a train station. The one dispensing beverages (cold and hot) came with a voice that thanked us for our business.

Bill, a translator of Japanese and Chinese literature, had been telling me about the Kiso Road for a long time. A resident of Miami, he had lived in Japan from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s and had already walked the Kiso twice. The road was officially established in 1601, but carried travelers as early as 703, according to ancient records. Bill loved the fact that, unlike the industrialized Tokaido, the Kiso Road remains very well preserved in places. Walking it, he had assured me, you could still get a feeling of long ago.

I had visited Japan once, taking trains from city to city. The idea of traveling on foot with a knowledgeable friend through a rustic landscape in a high-tech country was greatly appealing. The summer before our trip, Bill gave me the itinerary: we’d walk from Hideshio to Magome—about 55 miles—stopping in post towns along the way. We would act as if the automobile had never been invented. Then he suggested I read Before the Dawn.

“I hope there’s a professional masseuse in Narai,” Bill said, once we were walking again. “Or even an unprofessional one.”

Twenty minutes later, we got off the highway at the town of Niekawa and then dipped down into Hirasawa, passing lacquerware shops. When residents appeared, we double-teamed them with greetings of “Ohayo gozaimasu!” (“Good morning!”) Bill had taught me a few words.

A little before noon, Narai appeared in the distance as a thin town stretched along railroad tracks. We found its main street tight with dark wooden houses and day-tripping tourists. The sloping roofs, small shops, cloth banners and unmistakable air of cultural import were like a reward for having arrived on foot. But I doubted that Bill would find a masseuse.

He did find our ryokan, or inn, the Echigo-ya. Thin sliding doors open to the street gave way to an entryway with a dirt floor rimming a tatami platform. The innkeeper appeared upon it shortly, a young man in a head scarf who dropped to his knees to tell us at eye level that we were too early to check in. Leaving one’s bags never felt so good.

Bill led me to his favorite coffee shop, Matsuya Sabo, a cramped establishment in an antique style. Toy poodles, named Chopin and Piano by the shop’s music-loving owners, were in attendance, and a nocturne played softly behind the bar, which was hung with delicate paper lanterns.

The café proprietor, Mr. Imai, told us that in the old days processions would come through town bearing green tea for the emperor. If the tea container shattered, whoever caused the accident would be beheaded. So when a tea procession arrived, everyone stayed indoors without making a sound. Once it passed, they ran into the street to celebrate.

We ate a late lunch of zaru soba—the cold buckwheat noodles for which the region is famous—dipping them into a sweetened soy sauce spiked with scallions and wasabi. Outside, standing in the street, Bill pointed to the mountain rising at the southern edge of town. “That’s the dreaded Torii Pass,” he said, referring to the path we were destined to take over the mountain and employing the adjective he never failed to use when mentioning it.

His idea was that we would climb the mountain the next day—without backpacks—to Yabuhara, where we could take a train back to Narai to spend a second night before catching a morning train to Yabuhara to resume our walk. It struck me as a fine idea, and a historically sound one as well, for in the old days, packhorses were employed to carry belongings.

Dinner was served in our room, on a table with greatly abbreviated legs. Our chairs were limbless, consisting of a back and pillowed seat. Sitting was going to be a bigger problem for me than walking.

In the numerous bowls and plates in front of me sat pink-and-white rectangles of carp sashimi, shredded mountain potato in raw egg and seaweed, three fishes slightly larger than matchsticks, one grilled freshwater fish, a watery egg custard with chicken and mushrooms, boiled daikon (radish) with miso, and vegetable tempura.

The richness of the meal contrasted with the sparseness of the room. Bedding would be laid down on the tatami after dinner. There was no TV, but a small black rock sat on an embroidered pillow atop a wooden stand for our contemplation. A framed poem, which Bill translated, hung on one wall:

The taste of water

The taste of soba

Everything in Kiso

The taste of autumn

At home I begin my day with a grapefruit; in Japan I exchanged the fruit for a faux pas. Occasionally I would shuffle back to my room still wearing the specially designated bathroom slippers, which, of course, are supposed to stay in the bathroom. And this morning, the innkeeper asked if we would like tea before breakfast; eager to tackle the dreaded Torii Pass, I declined.

Bill had a brief discussion with the young man and then said to me firmly: “It’s the custom of the house.” The tea was served with great deliberation. “If you put in super hot water,” Bill explained, “you ‘insult’ the tea.” (One insult before breakfast was enough.) And this was gyokuro, considered by some to be the finest green tea. Slowly, the innkeeper poured a little into one cup, and then the other, going back and forth in the interest of equality.

After breakfast (fish, rice, miso soup, seaweed), we walked out of town and headed up the mountain. Large flat stones appeared underfoot, part of the Kiso Road’s original ishidatami (literally “stone tatami”), which had been laid down long ago. I thought of Hanzo and his brother-in-law scampering over this pavement in straw sandals on their way to Edo.

The path narrowed, steepened and turned to dirt. We worked our way through windless woods. (Here—if you ignored my panting—was the quiet we’d been promised.) Switchbacks broke the monotony. Despite the cold air, my undershirt was soaked and my scarf damp.

An hour and a half of climbing brought us to level ground. Next to a wood shelter stood a stone fountain, a ceramic cup placed upside down on its wall. I filled it with water that was more delicious than tea. Bill couldn’t remember which path he had taken the last time he was here (there were several) and chose the one that went up. Unfortunately. I had assumed our exertions were over. Now I thought not of Hanzo and his brother-in-law, but rather of Kita and Yaji, the two heroes of Ikku Jippensha’s comic novel Shanks’ Mare, who walk the Tokaido with all the grace of the Three Stooges.

We shambled back down to the shelter and were pointed in the right direction by a Japanese guide leading a quartet of Californians. It took us about 45 minutes to descend into Yabuhara, where we were soon huddled next to a space heater in a restaurant that specialized in eel. A large group of Americans filed in, one of whom looked at us and said, “You’re the guys who got lost.” News always did travel fast along the Kiso Road.

After taking the train back to Narai, we moved to a minshuku, which is like a ryokan but with communal meals. In the morning, the innkeeper asked if she could take our picture for her Web site. We posed and bowed and then headed off in a light rain to the train station, turning around occasionally to find our hostess still standing in the raw air, bowing farewell.

Yabuhara was deserted and wet, our ryokan somber and cold. (Even in the mountains, we encountered no central heating.) We were served a delicious noodle soup in a dark, high-ceilinged restaurant, where we sat at a vast communal table. For dessert—a rare event in old Japan—the chef brought out a plum sorbet that provided each of us with precisely one and a half spoonfuls. Leaving, we found our damp shoes thoughtfully propped next to a space heater.

In the morning, I set off alone for the post town of Kiso-Fukushima. Bill had caught a cold, and the Chuo-sen (Central Line) train—fast, punctual, heated—was always temptingly close at hand. Today he would ride it and take my backpack with him.

At a little past 8 a.m. the air was crisp, the sky clear. I rejoined Route 19, where an electronic sign gave the temperature as 5 degrees Celsius (41 degrees Fahrenheit). A gas station attendant, standing with his back to the pumps, bowed to me as I walked past.

It wasn’t exactly a straight shot to Kiso-Fukushima, but it was a relatively flat one, of about nine miles. The second person I asked for directions to the inn—“Sarashina-ya doko desu ka?”—was standing right in front of it. A familiar pair of hiking boots stood in the foyer, and a man in a brown cardigan led me along a series of corridors and stairs to a bright room where Bill sat on the floor, writing postcards. The window behind him framed a swiftly flowing Kiso River.

On our way to find lunch, we passed a little plaza where a man sat on the pavement soaking his feet. (This public, underground hot spring had removable wooden covers, and it reminded me of the baths in our inns.) Farther along, a woman emerged from a café and suggested we enter, and so we did. This was a far cry from the gaggles of women who, in the old days, descended upon travelers to extol their establishments.

Kiso-Fukushima was the largest town we had seen since Shiojiri, and I remembered that in Before the Dawn, Hanzo walked here from Magome when called to the district administrative offices. Houses dating to the Tokugawa shogunate (which lasted from 1603 to 1868) lined a street that Bill said was the original Nakasendo. Across the river, the garden at the former governor’s house provided a beautiful example of shakkei, the practice of incorporating the surrounding natural scenery into a new, orchestrated landscape. The old barrier building—a kind of immigration and customs bureau—was now a museum. Shimazaki wrote that at the Fukushima barrier, officials were always on the lookout for “departing women and entering guns.” (Before 1867, women needed passports to travel the Kiso Road; moving guns over the road would have been taken as a sign of rebellion.)

The house next door to the museum was owned by a family that one of the Shimazakis had married into, and a display case held a photograph of the author’s father. He had posed respectfully on his knees, his hands resting on thick thighs, his hair pulled back from a broad face that, in shape and expression (a determined seriousness), reminded me of 19th-century photographs of Native Americans.

Back at our minshuku, Bill pointed out a wooden frame filled with script that hung in the foyer. It was a hand-carved reproduction of the first page of the Before the Dawn manuscript. “The Kiso Road,” Bill read aloud, “lies entirely in the mountains. In some places it cuts across the face of a precipice. In others it follows the banks of the Kiso River.” The sound of that river lulled us to sleep.

At breakfast Mr. Ando, the man in the brown cardigan, invited us to a goma (fire) ceremony that evening at his shrine. Bill had told me that Mr. Ando was a shaman in a religion that worships the god of Mount Ontake, which Hanzo had climbed to pray for his father’s recovery from illness. Shimazaki called it “a great mountain that would prevail amidst the endless changes of the human world.” I had assumed he had meant its physical presence, not its spiritual hold. Now I wasn’t so sure.

We ate a quick dinner—a hot-pot dish called kimchi shabu shabu and fried pond smelts—and piled into the back seat of Mr. Ando’s car. I had a strange feeling of exhilaration as I watched houses zip by (the response of the walker who is given a lift). We careered up a hill, at the top of which Bill and I were dropped off in front of a small building hung with vertical banners. Mr. Ando had temporarily ceased shaman service because he had recently become a grandfather.

Inside, we took off our shoes and were given white jackets with blue lettering on the sleeves; the calligraphy was in a style that Bill couldn’t decipher. About a dozen similarly garbed celebrants sat cross-legged on pillows before a platform with an open pit in the middle. Behind the pit stood a large wooden statue of Fudo Myo-o, the fanged Wisdom King, who holds a rope in his left hand (for tying up your emotions) and a sword in his right (for cutting through your ignorance). He appeared here as a manifestation of the god of Mount Ontake.

A priest led everyone in a long series of chants to bring the spirit of the god down from the mountain. Then an assistant placed blocks of wood in the pit and set them ablaze. The people seated around the fire continued chanting as the flames grew, raising their voices in a seemingly agitated state and cutting the air with their hands in motions that seemed mostly arbitrary to me. But Bill told me later that these mudras, as the gestures are called, actually correspond to certain mantras.

Bill joined in chanting the Heart Sutra, a short sutra, or maxim, embodying what he later said was “the central meaning of the wisdom of Emptiness.” I sat speechless, unsure if I was still in the land of bullet trains and talking vending machines.

Each of us was handed a cedar stick to touch to aching body parts, in the belief that the pain would transfer to the wood. One by one, people came up, knelt before the fire and fed it their sticks. The priest took his wand—which, with its bouquet of folded paper, resembled a white feather duster—and touched it to the flames. Then he tapped each supplicant several times with the paper, front and back. Flying sparks accompanied each cleansing. Bill, a Buddhist, went up for a hit.

Afterward, we walked toward our shoes through a thick cloud of smoke. “You know what the priest said to me?” he asked when we were outside. “ ‘Now don’t catch a cold.’ ”

The next morning we set out in a light drizzle. The mountains in front of us, wreathed in wisps of cloud, mimicked the painted panels we sometimes found in our rooms.

Despite a dramatic gorge on its outskirts, Agematsu turned out to be an unremarkable town. Our innkeeper, Mrs. Hotta, told us over dinner that men in the area live quite long because they keep in shape by walking in the mountains. She poured us sake and sang a Japanese folk song, followed by “Oh! Susanna.” In the morning, she stood outside with only a sweater for warmth (we were wrapped in scarves and jackets) and bowed until we passed out of sight.

After a fairly level hike of about three and a half hours, we reached the town of Suhara around noon. An instrumental version of “Love Is Blue” floated from outdoor speakers. I looked back toward where we had started and saw folds of mountains that looked impenetrable.

Downtown consisted of gas stations and strip malls (Route 19 was still dogging us), and, as it was Sunday, restaurants were closed. We found our minshuku across the river and spent the afternoon in our room (now I was catching a cold), watching sumo wrestling on a flat-screen TV. Bill explained the proceedings—he was familiar with most of the wrestlers, a fair number of whom were from Mongolia and Eastern Europe—but it struck me as one sport I did not really need to see in high definition.

In the morning, outside of town, a woman sweeping leaves said, “Gamban bei” (“Carry on”) in a country accent that made Bill laugh. The only other time he’d heard the phrase was in a cartoon of Japanese folk tales. Strings of persimmons, and sometimes rows of daikon, hung from balconies. An engraved stone, placed upright atop a plain one, noted that “Emperor Meiji stopped and rested here.” At a small post office I mailed some postcards and was given a blue plastic basket of hard candies in return. The transaction seemed worthy of its own small monument.

We found myokakuji temple on a hill overlooking the town of Nojiri. The former priest’s widow gave us a tour of the interior: the statue of Daikoku (god of wealth), the rows of ihai (tablets commemorating the dead) and photographs of the 59 men from the village who had died in World War II. Before we left she produced two enormous apples as gifts and a few words of English for us. “May you be happy,” she said, with an astonishingly girlish smile. “See you again.” Then she stood and bowed till we turned the corner.

The next day’s walk to Tsumago—at ten miles, our longest leg—began in a cold rain. There was a final trudge along Route 19, followed by a climb of about a mile that almost made me long for the highway.

Descending into Midono, we splashed into a coffee shop with a dank feeling of defeat. But a plate of zaru soba, and a change of undershirts in a frigid men’s room, worked their magic. We hoisted our backpacks and walked out of town.

The rain, which we had cursed all morning, now washed everything in a crystalline light. We looped past a waterwheel and a shed whose roof was held down with stones, then dropped dreamily into a town of street-hugging houses with overhanging eaves and dark slatted facades. The ancient, unspoiled air reminded us of Narai (as did the busloads of Japanese tourists), but there was something about the contours—the undulating main street, the cradling mountains—that made Tsumago feel even more prized.

Also, it was our last overnight stop before Magome, and the hometown of Shimazaki’s mother (and, in Before the Dawn, of Hanzo’s wife). The honjin—the house and inn of her family—was now a museum. You could also visit, down the street, old lodgings for commoners. With their dirt floors extending beyond the entryway, and bare platforms, they made our inns seem regal.

Our ryokan, the Matsushiro-ya, sat on a lane that descended from the main street like an exit ramp into a fairyland. The interior was a taut, austere puzzle of short stairs and thin panels, low ceilings and half-light that befit an inn that has been in the same family for 19 generations. Stretched out on the tatami, I could not have been anywhere but Japan, though in just what century was unclear.

In the morning, along with the usual fish, greens and miso soup, we each got a fried egg in the shape of a heart.

Just off the main street we found a coffee shop, Ko Sabo Garo, which doubled as a gallery selling paintings and jewelry. When I asked what was upstairs, Yasuko—who ran the café with her husband—climbed the steps and, hidden from view, sang a haunting song about spring rain while accompanying herself on the koto, a traditional stringed instrument. “That was so Japanese,” Bill said of her unseen performance. “Everything indirect, through shades, through suggestion.”

After dinner I took a walk. (It was becoming a habit.) Like many small tourist towns, Tsumago emptied by late afternoon, and in the darkness I had the place to myself. Hanging lanterns lent a soft yellow glow to dark shuttered shops. The only sound was the trickle of water.

For our walk to magome, Bill tied a small bell to his backpack—the tourist office sells bells to hikers for warding off bears. Past a pair of waterfalls, we began our final ascent on a path free of predators but thick with the spirit of Hanzo. Of course, this last test for us would have been a stroll for him. And there would have been no restorative tea near the top, served by a man in a conical hat.

“He says we have another 15 minutes of climbing,” Bill said, tempering my joy.

And we did. But then we started down, emerging from the forest as well as the mountains; a scenic overlook appeared, from which we could see the Gifu plain far below.

Magome was more open than I had pictured it, its houses and shops tumbling down a main pedestrian street and looking out toward a snow-patched Mount Ena. Because it had been rebuilt after a disastrous fire, the town had the feel of a historical re-creation. A museum to Shimazaki, on the grounds of the old family honjin, offered a library and a film on the writer’s life, but less of a feeling of connection than our walk in the woods.

At the Eishoji Temple, on a hill at the edge of town, the priest had added a small inn. We were shown the Shimazaki family ihai, and our room, whose walls were literally rice-paper thin.

It was the coldest night yet. I woke up repeatedly, remembering two things from Before the Dawn. One was an old saying of the region: “A child is to be brought up in cold and hunger.” The other was Hanzo’s attempt, near the end of the novel, to burn down the temple in which we now shivered. (He ended his days a victim of madness.) I didn’t want to see the temple damaged, but I would have welcomed a small fire.

We set out early the next morning, walking past fields dusted with frost. In a short while we came to a stone marker. “From here north,” Bill translated, “the Kiso Road.” Added to my sense of accomplishment was a feeling of enrichment; I was emerging from 11 days in a Japan that previously I had only read about. There were no witnesses to our arrival, but in my mind I saw—as I see still—bowing innkeepers, caretakers and gas station attendants.

Thomas Swick is the author of the collection A Way to See the World. Photographer Chiara Goia is based in Mumbai.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.