A Whirlwind Tour Around Poland

The memoirist trades Tuscany for the northern light and unexpected pleasures of Krakow and Gdansk

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Vistula-river-Wawel-Castle-Krakow-Poland-631.jpg)

In 1990, when my husband, Ed, and I bought an abandoned villa in Tuscany, we hired three Polish workers to help us restore a major terrace wall. They were new immigrants, there for the money, and not happy to be out of their homeland. At lunchtime, we saw them opening cans of sausages, sauerkraut and other delectables they could not live without. On holidays they drove north in a battered car of some unrecognizable make to Wrocław, a 26-hour trip, where they had left children and wives. They returned with big gray cans of food so they did not have to eat the dreaded Italian pasta. They were gallant. With neat bows, they kissed my hand.

The Poles were over-the-top, full-out workers. They hardly paused. We used to say, "Take a break. Get some rest."

They always replied, "We can sleep in Poland."

We adopted the response. Anytime we want to push through a project, we remind each other, "We can sleep in Poland."

Now we are going. To sleep but even better to wake up and find ourselves in a language full of consonants, a history that haunts, a poetry we have loved, a cuisine of beets, sausage and vodka, a landscape of birch forests and a people so resilient they must have elastic properties in their DNA.

We fly into Krakow at dusk and step outside into balmy air. The taxi drivers, all wearing coats and ties, stand in a queue. Soon we are slipping through narrow streets, passing lamp-lit parks and glimpses of the Vistula River. We turn onto cobbled Ulica (street) Kanonicza, named for canons who lived in the regal palaces there. "You will be staying on the most beautiful street," the driver tells us. He points to number 19/21, where Pope John Paul II once lived. Noble inscriptions in Latin cap carved doorways, and through upstairs windows I see painted beamed ceilings. Our hotel, the Copernicus, reflects an exciting blend of old and new. The candlelit lobby, once the courtyard, is now glassed over and verdant with plants hanging from inside balconies. A grand piano seems to be waiting for Chopin to sweep in and pound out a mazurka. The manager points out 15th-century ceilings, murals of church fathers, botanical motifs and gothic-lettered hymns from the 16th century.

I experience the delicious shock of the foreign as we step out and walk along the lower walls of the massive Wawel Royal Castle complex, where kings and queens of Poland are enjoying their long rest in the cathedral. We turn into a swath of deep green as twilight seeps into dark. When medieval walls were demolished in 1807 and the moat drained, this space became, by the 1820s, Planty Park, which rings the old town and provides a civilized promenade.

We pass a Ukrainian restaurant, shops selling amber jewelry, and strolling Krakovians—newly out of their coats, no doubt—in the spring evening.

"They look like my cousins," Ed remarks. He was raised in a Polish neighborhood in Winona, Minnesota. The relatives of his American-born parents immigrated from Kashubia in northern Poland, some in the 1830s, some during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, others as recently as 1900. Many other Poles from Kashubia also made their way to Winona as well.

We double back to the hotel, where dinner in the intimate, candlelit dining room nicely ends this travel day. When the waiter brings out an amuse-bouche of spicy salmon topped with cucumber sorbet, we know we're in good hands. Dumplings are light, with spinach and shrimp. We feast on duck, accompanied by parsley ice cream and roasted artichokes. Where's the sausage and potato? If they were on the menu tonight, they would be transformed by the masterful hand of Chef Marcin Filipkiewicz.

As we step outside in the morning, the city is just awakening. Pretzel stands appear on almost every block. Choose a string of small pretzel rings, or round ones as big as a face—plain, salted or sprinkled with poppy seeds. Skinny trolleys seemingly straight out of 1910 run through the streets. In Krakowski Kredens, a food shop, we see crocks of lard with onion or bacon, thin ropes of sausages, big blood sausages and cunning little hams and pâtés. Confitures—such an array—remind me of Ed's first words after landing: "I've never seen so many fruit trees."

Suddenly, the market square of Krakow appears. Magnificent! The Rynek Glowny is the great piazza of Europe— Siena and Brussels notwithstanding. Only Venice's San Marco compares in scope, and Krakow's is more visually exciting. Because nothing in the old town could be built higher than the cathedral, the scale remains human. We're stunned by intact neo-Classical buildings with Renaissance, Baroque and Gothic touches. Spared from World War II bombing, the enormous space breathes Old World.

We take a slow promenade all the way around. On a warm, late April morning, everyone is outside, some under the umbrellas of outdoor cafés, some showing winter-pale faces to the sun. Krakow has some 170,000 students, and many of them are walking around or gathered at tables over formidable glasses of beer.

The Sukiennice, the medieval Cloth Hall, stands in the center of the Rynek, and the sweet Romanesque church of St. Adalbert—older than the square—is incongruously angled into a corner. The Cloth Hall, begun in the 13th century by the charmingly named Boleslaw the Chaste, now houses a gallery, an arcade of craft and souvenir stalls and the atmospheric 19th-century Noworolski Café. How many coffees can we drink? I want to pause at each cardinal point in the square and admire a new perspective. Spires, machicolations, towers, scrolls, turrets, whimsical stone rams, eagles, lizards—all lend endless variety. The flower vendors are favoring tulips today. I usually find mimes annoying but am charmed by one assuming the mien of a writer, all in brown at a café table, his pen poised over a notebook. Reminds me of writer's block.

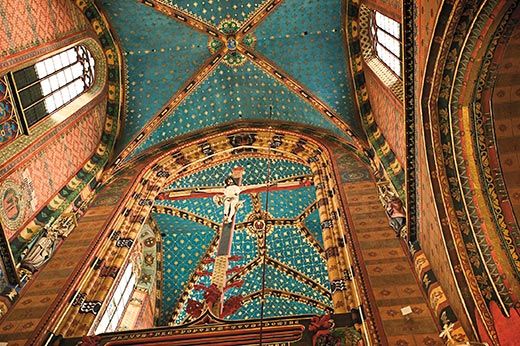

St. Mary's, one of Krakow's most venerated churches, watches over the square, as does the statue of 19th-century poet Adam Mickiewicz. High on a pediment with a book in his hand, the poet now serves as a popular meeting point. We cross the square and look into St. Barbara's Church as well, but touring a Polish church feels awkward. So many people are praying that if you are just having a look, you're intruding.

Nearby we find the Czartoryski Museum, where Leonardo da Vinci's Lady With an Ermine lives. We saw her when she came to Italy for an exhibit, which was lucky because today her section of the museum is closed. She's one of four female portraits by da Vinci, and as enigmatic as the Mona Lisa.

Other pleasures we take in: Gypsy musicians, women on stools selling shaped breads, eggs from a basket and cloth-wrapped cheeses. So many bookstores! We stop in several to touch the volumes of favorite poets—Zbigniew Herbert, Wislawa Szymborska, Adam Zagajewski and Czeslaw Milosz, all profoundly conscious of history, full of layers of darkness and gorgeously suffused with wit. We happen upon the covered market, where we feast visually on radishes, kohlrabi, strawberries, possibly every sausage known to man, shoppers with baskets, and farm women in bold flowered scarves and aprons.

At midmorning, we pause at A. Blikle and indulge in its caramel walnut tart and hazelnut cream tart. "As good as Paris!" Ed declares. The espresso, too, is perfect. A mother feeds her baby girl bites of plum cake, causing her to bang enthusiastically on her stroller.

We come upon Ulica Retoryka—Rhetoric Street—where Teodor Talowski designed several brick houses in the late 19th-century. A grand corner building adorned with a stone frog playing a mandolin and musical scores incised across the facade is called "Singing Frog." Another is inscribed "Festina Lente," the Renaissance concept of "make haste slowly," which I admire. Talowski's arches, inset balconies, fancy brickwork and inscriptions reveal a playful mind, while his solid forms and materials show a pre-Modernist architect at work.

We walk across the river to the Kazimierz district, founded as a separate town in 1335 by Casimir the Great. By 1495, Jews driven out of Krakow settled here. Now local publications call Kazimierz trendy. Around a pleasant plaza surrounded by trees are a few cafés, two synagogues and restaurants serving Jewish food—all are hopeful markers. I can see how it might become trendy indeed, though I wonder whether any of the 1,000 Jews remaining in the city would choose to live in this district historied by extreme persecution. Ed is handed a yarmulke as we stop at Remu'h Synagogue, where two rabbis quietly read the Torah. Light inside the white walls of the synagogue hits hard and bright, but the adjoining cemetery, destroyed by the Germans and later restored, seems eerily quiet under trees just leafing. This neighborhood speaks to the riven heritage of Krakow's Jewish culture—mere remnants of the residents who were forced out, first to the nearby Ghetto, then to a worse fate.

Next we find the Podgorze district, which would seem ordinary had I not read of the rabid and heroic events that occurred in these courtyards, houses and hospitals. A memorial in the Plac Bohaterow Getta (Heroes of the Ghetto) commemorates the Jews who were gathered here, with only the belongings they could carry, before deportation to death camps. The Plac memorial consists of 70 metal chairs, symbols of the abandoned furniture of the some 18,000 Jews who were taken away from the Ghetto. Overlooking the memorial is the Eagle Pharmacy of Tadeusz Pankiewicz, who with three brave women employees, aided Ghetto residents with medicines and information. Stories like this one and Oskar Schindler's (his factory is nearby) are small victories in the deluge of evil and sorrow. A small green building facing the square was once the secret headquarters of the Resistance. Now it's a pizzeria. Ed says, "You come to these neighborhoods more to see what's not here rather than what is."

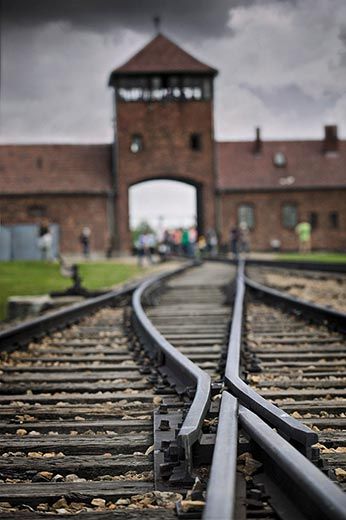

We hire a guide to take us to the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Birkenau. At Auschwitz, a glass-walled room displays 4,000 pounds of tangled hair; another room holds shoes and the pink sandals with kitten heels that some young girl wore there. In the sleeping quarters, Gregory, our guide, points out names in tiny handwriting near the ceiling, scrawled from the top bunk by a few of the prisoners. Approximately 1.1 million Jews perished at the two main Auschwitz camps, along with at least 70,000 non-Jewish Poles. Of the 3.3 million Jews in Poland before the war, only some 300,000 survived. Often lost in the horror of that statistic is that approximately 1.8 million non-Jewish Poles—ordinary people, Resistance fighters, intellectuals—also died at the hands of the Nazis. I notice a dented teakettle in the mound of everyday objects, and the gallery of ID photos, grim faces lining the halls—their eyes burn with foreknowledge of their fate. Seeing the settings of atrocities turns out to be different from what you experience from books and documentaries: a blunt physical feeling strikes, a visceral awareness of bodies and souls that perished.

Grasses and trees have softened Auschwitz. "Then, grass would have been eaten," Gregory says. Birkenau (Auschwitz II) is starker. It is the most monstrous of the many—Gregory says 50—concentration camps in the Krakow area, with its flat fields of chimneys, still standing after fleeing Germans torched the buildings and records, making it impossible to know exact death tolls. Enough structures remain to tell the tale. We file through bleak sleeping quarters, then the toilet barracks, four long concrete rows with holes over gutters below. "Guard duty here was prized," Gregory tells us, "they got to inspect excrement for jewelry the prisoners swallowed."

Outside Birkenau, three people pick lettuces in a field. Has enough time gone by that no whiff of smoke, no mote of DNA settles on the leaves of their spring salads? I remember a line from the Nobel Prize-winning poet Wislawa Szymborska: Forgive me distant wars, for bringing flowers home.

First stop the next morning: Cmentarz Rakowicki, founded outside Krakow's Old Town in 1803 by the ruling Austrians, who thought cemeteries in populated areas caused epidemics. I like wandering in cemeteries, partly because you can tell much about a culture by how they bury their dead and partly because they're often surpassingly lovely. Here plum and cherry trees bloom along lanes crowded with Gothic chapels, hovering angels and sorrowing women. If I lived here, I'd come often for the warming rays of sun falling on mossy crosses and stone lambs. Gregory tactfully says we can linger, but we move on to Nowa Huta, where more than 200,000 of Krakow's 757,000 residents live.

In 1949, during the Soviet Union's dismal sway over Poland, the Communist authorities began this development as well as the pollution-belching steelworks about six miles from central Krakow. Workers' families who'd never had running water flocked to live in the planned community but were soon disenchanted with working conditions, pollution and the lack of a church. Sixty years on, the huge gray apartment blocks have retained their austerity, but now trees have matured and open spaces make the neighborhoods friendlier. The steel mill has not been entirely cleaned up, but it no longer spews soot over everything. The arcaded central plaza was modeled loosely on Piazza del Popolo in Rome. When we look closely, we see Renaissance touches on balustrades and windows. If only the buildings' facades were not heavy gray.

Near Nowa Huta, we see my favorite Krakow church, part of a 13th-century Cistercian abbey, built near where a cross was found floating in the river. It's filled with hundreds of ex-votos, 16th-century frescoes and soaring arched columns in pale stone. Pilgrims making their way on their knees to a statue of Mary have worn paths in the marble. Strikingly, the side-aisle ceilings and vaulting are painted in traditional folk flower designs, with a bit of Art Nouveau flourish.

Poland has a curious tradition of memorializing its dead with earth mounds; the country has 250 of them. Early ones may be prehistoric or Celtic, no one knows for sure. Near Krakow, one commemorates Krak, the ancient king and namesake of the city, though excavations have found no sign of his burial. Another honors his daughter Wanda, who drowned herself rather than marry a German prince. We drive up to see the mound honoring the Polish independence fighter Tadeusz Kosciuszko and built in 1820-23 with wheelbarrows of dirt. He's also the American Revolutionary War hero whose name we butchered in fifth grade. A warrior as well as an engineer specializing in fortifications, his skills took him to many battlefields, including Saratoga in upstate New York. From this steep 34-yard-high cone with a spiraling path, you can see in the distance the mound of Krak. I like hearing that earth from Kosciuszko's American battle sites forms a part of the memorial.

At dusk, we take a last walk in the old heart of Krakow to the restaurant Ancora. Chef Adam Chrzastowski's cooking with plum, cherry and other fruit confitures exemplifies how he reinterprets tradition: he serves venison with onion and grape marmalade, his duck with a black currant and ginger one. Ed tries the cold, cold vodka with pepper and an oyster. One gulp or you're lost. Other delights: scallops wrapped in prosciutto, pear sorbet, chocolate soufflé with a surprise hint of blue cheese. It's late when Adam comes out and chats with us. Inspired by his grandmother's cooking and a sojourn in Shanghai, he moves Polish food into the bright future the country appears headed for as well.

The GPS in our rented Renault took us quickly out of Krakow, but the freeway soon petered out, dumping us onto two-lane roads interrupted by stoplights and road repairs. Town names are all consonants, with maybe a "y" thrown in, so we forget where we've passed, where we're headed. Ed is a blood-sport driver, but his training on Italian autostradas does no good; we're stuck behind people who poke.

The road parts fields of yellow weeds and roadside lilacs about to open. Just as I've praised the GPS, Ed discovers that we are lost, heading not north toward Gdansk but west toward the Czech border. Bucolic pleasures evaporate as we try to reprogram. The little dervish inside the GPS wants to go to Prague, though as we retrace, it seems to decide on Sarajevo. Every few minutes it twirls us off course. I become the navigator, spreading out a huge map on my lap. The GPS croaks sporadically from the floor.

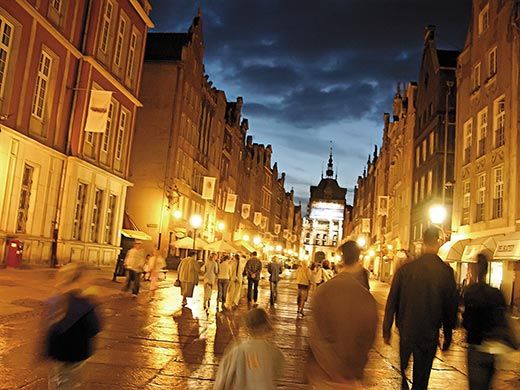

When we reach Gdansk, we easily find our hotel on the Motlawa River. An exquisite manor house from 1728 that escaped the bombings of the war, Hotel Podewils maintains an elegant, ladylike presence. Our room has windows on two sides, and I walk back and forth, watching fishermen, yachts and a scape of Gdansk's old town. The tall structure predominating the view I identify in my guidebook as the medieval crane that hoisted goods from the granary to barges below. Like most of Gdansk, it was restored after the leveling of the city at the end of World War II.

The Ulica Dluga, the city's main thoroughfare, is lined with outrageously ornate houses of ocher, dusty aquamarine, gold, peach, pea green and pink. One house is white, the better to show off its gold bunches of grapes and masterful stucco work. Facades are frescoed with garlands of fruit, mythological animals or courtiers with lutes, while their tops are crowned with classical statues, urns and iron ornaments. The houses, deep and skinny, have front and back staircases and connected rooms without corridors. At one of the houses, Dom Uphagena, we're able to explore inside. I love the decorated walls of each room—one with panels of flowers and butterflies on the doors, one painted with birds and another with fruit.

The Hanseatic League, a guild of northern cities, originally formed to protect salt and spice trade routes, thrived from the 13th through the 17th centuries. The powerful association grew to control all major trade in fish, grain, amber, fur, ore and textiles. Gdansk was perfectly situated to take advantage of shipping from the south, traveling down the Vistula River to the Baltic. The ornamentation in this city reveals that the powerful Hanseatic merchants and their wives had sophisticated taste and a mile-wide streak of delight in their surroundings.

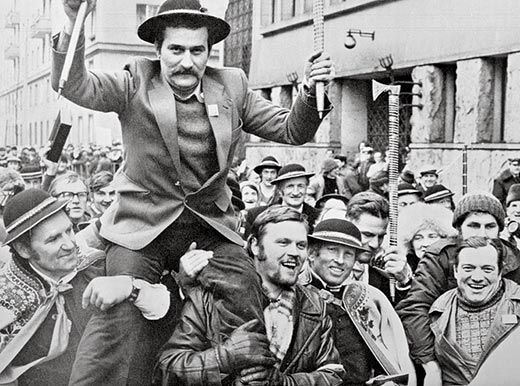

It's moving to think of the Poles accomplishing this loving and masterful restoration of their destroyed city after the war, especially as they did not share in the good fortune of funds from the Marshall Plan and, to boot, were handed over to the Soviet Union by Churchill, Stalin and Truman. The recovery in Gdansk seems as miraculous as the 1980s rise of the Solidarity movement in the shipyard here. I look for Lech Walesa, who now lectures around the world after having served as president in the 1990s, on the streets. His transformation from labor organizer into national hero changed history when his union's protests led to others throughout Poland. The movement he started with a shout of defiance eventually broke the Soviet domination. He must revel in the palpable energy of the new Poland. The schoolchildren we see everywhere are a prime example: they are on the move, following their teachers to historic sites. Boisterous and playful, they easily symbolize new directions; even the teachers seem to be having fun.

Amber traders plied the Baltic for centuries. At the Amber Museum, we see medieval crosses, beads, amulets and modern jewelry studded with amber, as well as snail shells, dragonflies, fleas, animal hair and feathers suspended in it. Baltic amber (succinite), known for its high quality, was formed from the fossilized resin of ancient conifers, which fell into Scandinavian and other northern European rivers and traveled to sea. Some of the museum specimens date back to the Neolithic era, when pieces were found washed up on shore. Later, collectors scooped amber from the seafloor, estuaries and marshes. As early as 1477, Gdansk had a guild of amber craftsmen.

We explore Stare Miasto, another historic section, with its grand gristmill on a stream, churches with melodic bells and the Old Town Hall from 1587, one of the few buildings to survive the war. In St. Nicholas, also a survivor, we happen to arrive just as an organist begins to practice. Piercing, booming music fills every atom of the dramatic and ornate church and transports the prayers of the devout toward heaven.

We trek to the National Museum to see the Hans Memling Last Judgment triptych. Possibly pirate booty, it appeared in the city around 1473. Later, Napoleon sent it off to Paris for a while, but Gdansk was later able to reclaim it. The museum seems to have a Last Judgment focus; the subject recurs in the rooms of Polish painters of the 19th and 20th centuries. The concept of renewed life must resonate deeply in a city that literally had to rise from ashes.

On our last day we engage a guide, Ewelina, to go with us into Kashubia to seek traces of Ed's relatives. "When did you see Poland really start to change?" I ask her.

"Solidarity, of course. But three signs woke us up. Having a Polish pope—that was so important back in '78. Then the Nobels coming to two of our poets, to Czeslaw Milosz—and we didn't even know about this Pole in exile—in 1980, then Wislawa Szymborska, that was 1996. The outside confirmation gave us pride." She glances out the window and sighs. "Those three events I can't overemphasize. We thought maybe we can do something." She tells us that many immigrant Poles are coming home, bringing considerable energy back to their country. Around 200,000 left England in 2008, both educated Poles and workers, lured home by opportunities created by European Union money given to Poland, Britain's bad economy and rising wages in Poland. "This is good, all good," she says.

Ed has some place names, so we drive west for two hours to the castle town of Bytow, then through forests carpeted with white flowers. Shortly, we come to tiny Ugoszcz. Without Ewelina, we would have found nothing, but she directs us to stop for directions, and we follow as she marches up to the priest's house. To our surprise he answers, takes our hands with metacarpal-crushing handshakes, brings us inside and pulls out old ledgers with brown ink calligraphy recording baptisms back to the 1700s. He's utterly familiar with these books. As Ed says the family names, he flips pages and calls out other names well known in Minnesota. He locates grandmothers, great- and great-great-uncles and aunts, great-great-grandfathers, some who left, some who stayed. He copies two certificates in Latin and Polish and gives them to Ed. One, from 1841, records the birth of his great-grandfather Jacobus Kulas; the other, from 1890, records that of his grandmother Valeria Ursula Breske. We visit the 13th-century church across the road, a wooden beauty, where relatives were baptized.

Driving back to Gdansk, Ed is stopped for speeding. The young officers seem intrigued that they have caught Americans. Ewelina explains that Ed has come all this way to find his ancestors. They look at his license and ask him about his family. "Oh, lots of Kleismits in the next town," says one. They let us go without a fine.

Ewelina tells us we must see the Art Nouveau sea resort Sopot. Ed wants to visit Bialowieza, the primeval forest with roaming bison. I'd like to see Wroclaw, where our Polish workers lived. Although we've slept well in Poland, the best trips make you feel more awake than ever. On the way to the airport, Ed gazes dreamily at cherry trees whizzing by the window. Just as I check my calendar for when we might return, he turns and says, "Shall we come back next May?"

Frances Mayes' Every Day in Tuscany will be published in March 2010. She lives in North Carolina and Cortona, Italy.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.