A Yankee in China

William Lindesay follows the trail of forgotten traveler, William Edgar Geil, the first man to traverse the Great Wall of China

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/great-wall-sidebar-631.jpg)

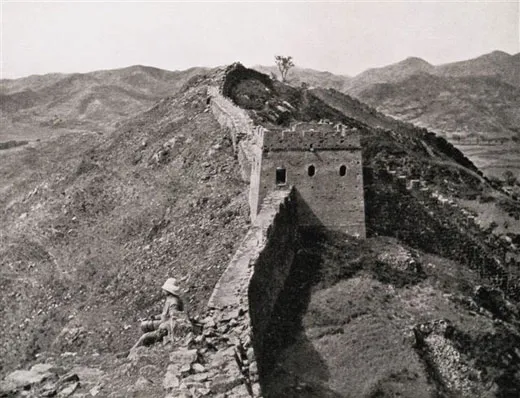

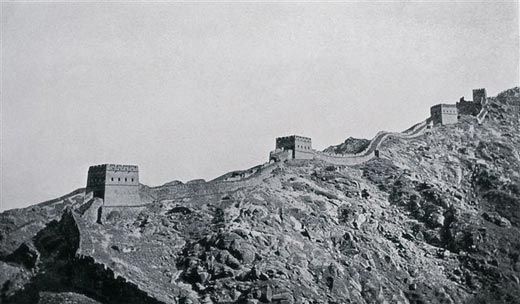

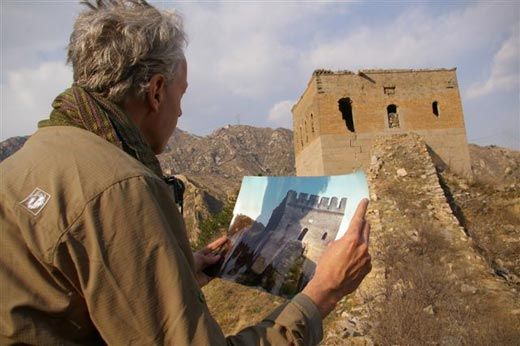

In 1990, William Lindesay, a British authority on the Great Wall, Beijing, happened upon a copy of The Great Wall of China, a travelogue by William Edgar Geil—very likely the first individual, Chinese included—to traverse the entire Great Wall of China, at the turn of the century . Lindesay himself is the author of Alone on the Great Wall, an account of on his own 1,500-mile excursion in 1987. Lindesay thumbed through the book, transfixed by the photographs, particularly one showing Geil near a tower on a remote section of the wall. Lindesay possessed his own photograph of that very site; however, by the time he arrived there in 1987, the tower visible in Geil's image had vanished. "It's from this experience that I first thought, the wall William Geil saw before me was much greater," says Lindesay. "The towers were grander, and when I got there, things had changed."

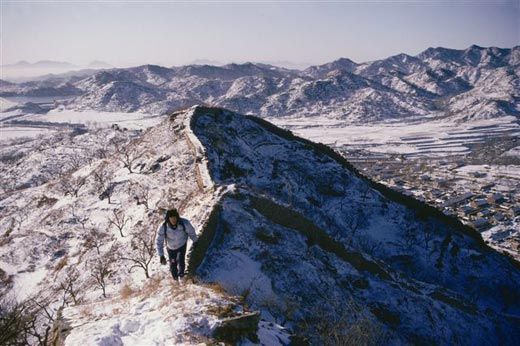

Lindesay began poring over Geil's photographs. Beginning in 2004, he set out to locate and re-photograph the sites depicted in Geil's pictures. "It was really exciting to find the exact spot, frame up the picture and think that many decades before, William Geil was here," Lindesay recalls. Since then, he has traveled more than 24,000 miles, photographing many of the sites documented by Geil , as well as a number of additional locations along the wall.

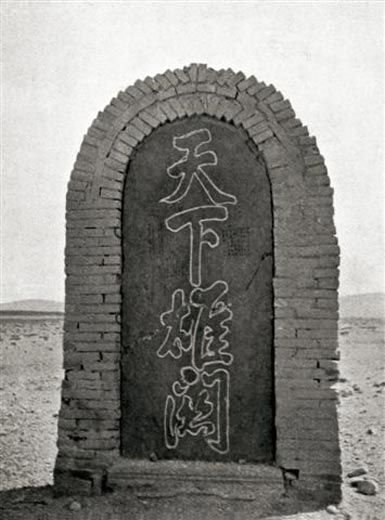

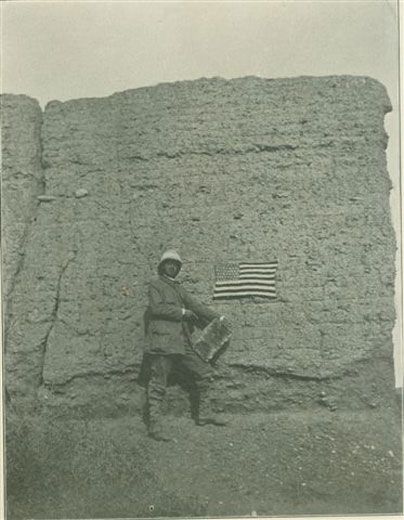

Lindesay's then-and-now images, to be published this September in The Great Wall Revisited, document changes to the wall in the last century, an issue of particular interest to Lindesay. He is the founder of International Friends of the Great Wall, a nonprofit focusing on the wall's protection. But almost of equal interest to Lindesay are the "stories behind the pictures." Every time he looks at the closing photograph in Geil's book—the explorer standing proudly at the western end of the wall—Lindesay wonders how it is that the intrepid Geil could be so little celebrated in the United States.

Born in 1865, Geil had a thirst for adventure. In addition to traveling the length of the wall, he trekked across equatorial Africa, traveled down the Yangtze River, sailed the South Seas and visited the 18 capitals of China's provinces. Geil was a Baptist missionary, but his curiosity prompted exploration far beyond the scope of his Christian duties. He documented his four-month, 1,800-mile trip along the Great Wall in 1908 with photographs and detailed field notes, writing the first book on the wall upon his return. It was his intent to be "so complete that the future historian of the Wall would find little to write about unless he pirated our notes," and so established himself as an explorer, writer and lecturer of international fame. When he died of influenza in Italy in 1925, he allocated $3,000 in his will to commissioning his biography, noting, "My life has been unusual, and the story of it is likely to benefit young people."

But his fame was fleeting. Aside from a few obscure sources—his biography; his own books about his adventures, one being The Great Wall of China; and some newspaper clippings—he left no lasting legacy. His wife, devastated by his death, never recovered enough to promote his memory. Geil had no children. His personal effects were scattered and sealed under lock and key at private residences. He was virtually forgotten, his name left out of textbooks, museums and even the lore of his native Doylestown, 25 miles northeast of Philadelphia.

In the past few years, Lindesay has made attempts to track down Geil's descendents. Last fall, he learned that William Edgar's widow Constance Emerson Geil, had adopted a child (likely her cousin's daughter) after her husband's death. Eventually, Lindesay located John Laycock, one of Geil's adoptive grandsons and the self-described "family historian."

As it turns out, John Laycock, 63, an Episcopal priest in Grand Haven, Michigan, is sitting on a treasure trove. He is the keeper of a some of Geil's travel-related memorabilia: a bow and poisoned arrows from pygmies he encountered in Africa; an American flag; glass lantern slides used to illustrate his lectures; a tin of negatives; a colorfully embroidered Chinese mandarin outfit; books of rubbings and two or three bound volumes of his field diary. Laycock, who was 15 years old and living in nearby Abington, Pennsylvania, when his grandmother died in 1959, discovered a steamer trunk containing the curios in Geil's study—a dusty room kept largely as Geil had left it—when the family was preparing the estate, known as the Barrens, for sale in the summer of 1960.

"We have over the years regarded him as an eccentric uncle who was really fascinated by travel and did an enormous amount of it," says Laycock. "But we had little sense of the importance of his work, particularly his photographs."

Meanwhile, this past February, just as Lindesay was corresponding with Laycock, 21 tin boxes of Geil memorabilia landed in the hands of Tim Adamsky, an amateur historian with the Doylestown Historical Society. Walter Raymond Gustafson, a local bibliophile who had purchased the materials at an auction at the Barrens in 1960, had died in 2005. Gustafson's children were donating the collection. "From the beginning my dad had a sense of being the preserver of these papers," says Marilyn Arbor, Gustafson's daughter. The donations have now been catalogued. Adamsky reports the existence of manuscripts; a flag sewn by pygmies; photographs of Geil; letters; personal effects such as his eyeglasses, pocket watch and compass; newspaper clippings; Bibles; missionary pamphlets and ten or so field diaries.

"Our next big exhibit is going to be on William Edgar Geil," says Adamsky, who is aiming for next summer. "His hometown should know who he is."

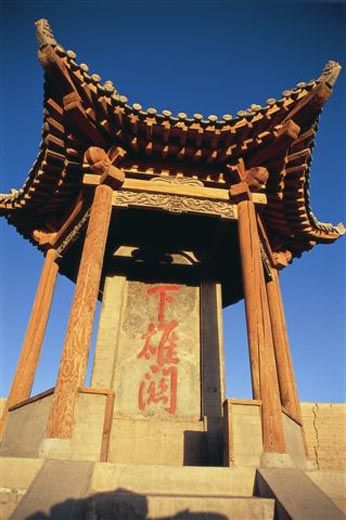

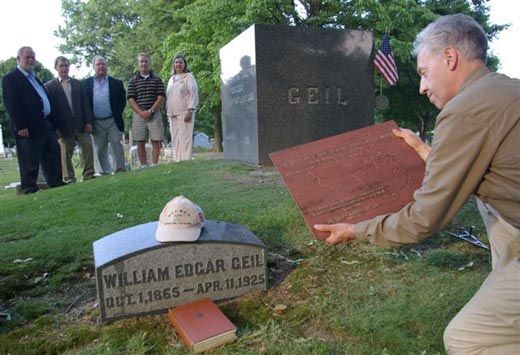

Lindesay visited Doylestown in June. There, he met John Laycock; assessed the donations to the Doylestown Historical Society; visited Geil's grave in Doylestown Cemetery and toured the Barrens — a 10,000-square-foot, Italian Victorian mansion complete with molds of the stelae at either end of the Great Wall on the exterior of the house and a replica of a Chinese pagoda in an adjacent property. He has been granted access to the Doylestown Historical Society's newly acquired collection and is planning an exhibition at Beijing's Imperial Academy to begin on October 16 and run until the end of the year.

"[I] certainly [hope] to gain recognition of William Geil's achievements," says Lindesay. "That's already been done here in China, but I hope I can make Americans aware that William Geil was the first man to make a journey along this magnificent structure."

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)