Africa on the Fly

Dangling from a paraglider with a propeller on his back, photographer George Steinmetz gets a new perspective on Africa

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Steinmetz-salt-making-northern-Niger-631.jpg)

The children playing at the elementary school across the street from George Steinmetz's house didn't miss a beat when, grunting in his driveway, he strapped on his flying machine. His outfit was pure New Jersey dad—loafers, blue jeans and a fleece vest—but his hair was wild and the shadows beneath his eyes were as dark as the volcanic craters he likes to photograph from the sky. Steinmetz had been up until 3 that morning dangling from the rafters of his garage to test his new motorized paragliding harness. "To be honest, it's a big pain," he said as his assistant, Jessica Licciardello, yanked at the engine's cord, checking it before we headed out for a test flight. "But, you see, I'm the only one who takes pictures like this."

The motor caught, and suddenly the clipped grass of Steinmetz's front yard rippled like the African savanna. Even now, the kids didn't look over: perhaps they mistook the roar for a leaf blower or lawn mower or some other source of suburban hubbub. It was just as well. Steinmetz's 6-year-old twin sons, students at the school, have never watched their father paraglide, and their mother would like to keep it that way. They have, however, seen the panoramic photographs their dad takes while hanging from a red parachute hundreds and sometimes thousands of feet off the ground—shots of sandstone pillars in Chad's Karnasai Valley, flamingos gliding over the Namibian coast and other seldom-seen-from-above wonders that fill African Air, Steinmetz's new book.

"Most aerial photographers work from helicopters or little planes, but he goes up on this crazy little thing," says Ruth Eichhorn, director of photography for the German edition of GEO, one of many magazines, including Smithsonian, that has published Steinmetz's work. "He can go very low, so he can photograph people in the landscape, and he will go to places that nobody else will go. It's very, very dangerous work, but I think it's worth it."

Steinmetz's aircraft—he calls it "a flying lawn chair"—consists of a nylon paraglider, a harness and a backpack-mounted motor with a large propeller that looks like an industrial fan. "I am the fuselage," he explains. To lift off, he spreads the glider on the ground, cranks up the motor and runs a few steps when the right gust of wind comes along. Then, traveling 30 miles per hour, he can dip into craters and get close enough to thousands of sunbathing fur seals to smell their fishy breath.

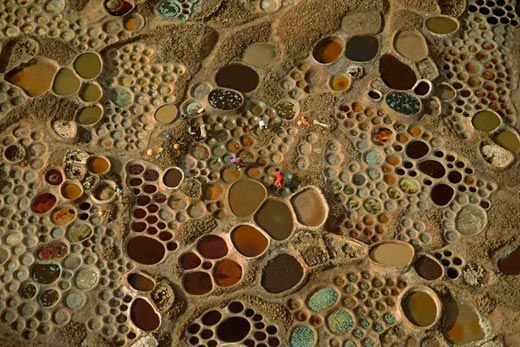

It might be easy to dismiss him as a real-life Icarus, the winged rogue of Greek myth who soared too near the sun. But Steinmetz flies to get closer to the earth; his Africa pictures convey a kind of intimacy that comes only with a certain distance. His perspective is lofty but not detached, and it's informed by his love of geophysics, which he studied as an undergraduate at Stanford University. His aerial pictures trace human patterns, too, in the slums radiating from Cape Town, South Africa, for example, or the crowds at a Soweto cemetery assembled for Saturday morning funerals.

"Africa has always been instinctive for me," he said as we drove, with the paraglider in pieces in the back seat of his Suburban, to a tiny airport nearby. As a young man on hiatus from college in the late 1970s, Steinmetz hitchhiked around Africa for a year, generally horrifying his mother back home in Beverly Hills. In Sudan, he once rode—and slept—for three days on the curved roof of a moving train. Somewhere along the way, he learned to take pictures with a borrowed camera. Even then, he recalled, he fantasized about photographing the continent from above. "I wanted to get into that landscape," he said. "I wanted to see Africa in 3-D."

He worked as a photographer's assistant in California before he began publishing his own work. Then, in 1997, when he was planning to take aerial photographs of the Central Sahara, his bush pilot backed out. Steinmetz decided to learn to fly himself, taking lessons in motorized paragliding, which does not require a pilot's license, in an Arizona desert. A few months later, he was sailing above salt caravans in Niger. In the next decade he flew over some of the world's most forbidding places, a flamboyant red blip against the clouds.

He uses a digital camera, usually with a wide-angle zoom lens, and has to juggle the camera and the paraglider's Kevlar steering lines. He's had several nasty spills, including a recent crash into a stand of trees in northwest China; he awoke on the ground to discover that a tree branch had pierced his cheek. His contraption—at less than 100 pounds, the lightest kind of motorized aircraft in the world—can be carried just about anywhere: on a camel's back, in the belly of a canoe or in the back seat of an SUV.

At the suburban airfield, Steinmetz pieced together the engine's flimsy-looking metal frame and donned a big white helmet, kneepads and his "wheels"—sturdy boots. This would be a test run for an assignment in Libya. His radio was on the fritz, but never mind: while airborne he would communicate with us on the ground through a series of kicks. Licciardello—who once upon a time thought she was taking an office job toning photographs—looked nervous. "OK, George," she said.

He spread the paraglider on the ground and waited for the wind.

Staff writer Abigail Tucker last wrote about the 16th-century painter John White.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.